An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Literature Reviews: Key Considerations and Tips From Knowledge Synthesis Librarians

Robin parker , mlis, lindsey sikora , mist.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author: Robin Parker, MLIS, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, [email protected] , Twitter @rmnparker

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains a glossary for literature reviews .

Corresponding author.

Graduate medical education (GME) educators and researchers are often on the hunt for rigorous literature reviews. Reviews summarizing evidence can inform practice and serve as examples to inspire faculty and trainee research projects. While each review type is unique, some common elements are applicable to all reviews. In this article, we describe these commonalities and offer tips based on our experience as knowledge synthesis librarians.

The steps of any given review may be overlapping or iterative. However, the review process for a robust and reproducible project should begin with a concrete plan for the conduct and reporting processes. The PIECES framework, proposed by Foster and Jewell, is a useful tool to guide researchers through the overarching phases of a review. 1 The PIECES acronym stands for: Planning the review, Identifying studies and resources, Evaluating and appraising the evidence, Collecting and combining data, Explaining the synthesis, and Summarizing the findings. A glossary of key review-related terms is provided as online supplementary data.

Putting the PIECES Together

P: planning the review.

The essential groundwork of a successful review involves developing a clear research question, along with inclusion and exclusion criteria. As will be described in more detail throughout this JGME Literature Review Series, the research question must align with the review type. While some questions are narrow in scope, defined before data collection, and precise (eg, systematic reviews), others are broad in scope, evolve over the course of the data collection and analysis, and become precise during the review process (eg, state-of-the-art reviews). In general, the research question should be both comprehensive and clear, with details about the key concepts: the population or problem; intervention, innovation, or exposure of interest; and particular learner, organization, or health outcomes. Researchers may use a question framework for either quantitative (eg, PICO [patient/population, intervention, comparison, outcome]) or qualitative questions 2 to guide formulation of the review steps. The review on theory in interprofessional education by Hean et al is an excellent example of using a structured question framework to inform search strategy development and inclusion criteria, when using a theory-oriented question framework. 3 , 4

Whether researchers write a formal review protocol or research proposal, as is strongly recommended for systematic and scoping reviews, authors should prepare for a substantial planning stage. Planning starts with developing and refining an appropriate research question(s), building a team, and selecting a suitable synthesis method.

Conducting a preliminary literature search, to confirm the need for a review and get an initial sense of the types and volume of data sources, is an important part of the planning stage. This search can include looking for other recent relevant syntheses and considering the methods choices of these existing reviews (eg, search strategy and inclusion criteria). Keep in mind that initially scanning the literature and refining the review question may be an iterative process, where the former can influence modifications to the latter.

From early stages it is important to determine the resources and technologies available to assist with the synthesis process. Citation management software, review management software, and data analysis and reporting tools should be considered in addition to bibliographic databases and journal subscriptions. The Table outlines the types of tools that can be used throughout the various stages of the review process, as well as the team members likely to have expertise in the skills and processes for each stage. For examples of existing tools, visit the Systematic Review Toolbox website 5 or the knowledge synthesis research guide from an institutional library ( Box ).

Useful Tools and Team Members for Review Projects

Abbreviation: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Box Useful Resources for Conducting Reviews

BEME Collaboration: https://www.bemecollaboration.org

Campbell Collaboration: https://www.campbellcollaboration.org

Cochrane Handbook: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

Systematic Review Toolbox: http://systematicreviewtools.com

Review typology articles:

Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S. Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Syst Rev . 2012;1:28. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-28

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J . 2009;26(2):91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol . 2018;18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Finally, the review team will need to discuss and decide on a list of inclusion and exclusion criteria. In other words, how will reviewers know whether a given article or other data source should be retained for the synthesis? Criteria could include population, type of publication, language, time period, type of study, and sample size, but will vary depending on the research question and type of review. These criteria can provide useful information about which keywords to include, which databases to search, and which other resources to use, if appropriate.

Pro Tip 1: Determine the ideal venue(s) for publication and consider the target audience during the planning phase to ensure alignment with the research question and purpose .

I: Identifying Studies and Resources

Identifying studies begins by searching the appropriate databases and is determined by the research question. Once database searches are complete, it may be important to supplement the search with studies that are not included in the databases. This often means conducting a supplemental search by reviewing conference abstracts, technical reports, association websites, and other grey literature resources (ie, research produced by organizations outside the traditional commercial or academic publishing and distribution channels).

It is important to work with an information specialist (IS), such as a librarian, to determine the most appropriate sources to search and the most efficient approaches to identify potentially relevant evidence. The IS can advise, or even help to develop, the search strategy using best practices for conducting and reporting searches. We recommend inviting an IS to join the review team or to serve as a consultant. 6 , 7 The IS expertise in conducting thorough searches, as well as reporting the process properly to enhance the rigor and reproducibility with new PRISMA-S (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses literature search extension) guidelines, 8 will strengthen the review. Information specialists can be found at academic and hospital libraries, by contacting professional medical associations, and through knowledge synthesis networks. If your project is not funded, many IS experts will provide at least some free consultation or may be invited to join the review team.

Pro Tip 2: For GME topics, don't forget to search education-specific databases such as the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Education Research Complete, or others at your institutional library .

E: Evaluating and Appraising the Evidence

Evaluating and appraising the evidence includes initially screening the retrieved studies or other data sources to determine eligibility, based on fit or relevance to the topic. For some review types, this may consist of a systematic screening of all studies to select those that meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. For others, researchers may use a more strategic and purposeful means of sampling the data to address the review question. In some cases, eligibility may also include meeting certain methodological quality standards. Some review methods will include a formal appraisal process, such as using a checklist to determine the risk of bias within the data source (eg, Cochrane risk of bias tool 9 or Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument 10 ), whereas other reviews may look for fit with the theoretical or conceptual framework of the issue being examined. Regardless of the method used, this evaluation and appraisal stage of the process involves winnowing all the data found in the search strategy to that which will best help the reviewers address the research question. This process can be depicted by the PRISMA flowchart that is included in some reviews, such as systematic and scoping reviews.

Pro Tip 3: Pilot your inclusion criteria with a sample (eg, 10% of the full set of retrieved records) to ensure the entire review team is clear on what should be included and how to operationalize the criteria. This will help improve the inter-rater reliability of the project .

Pro Tip 4: Consider using review management software to handle the large number of citations and facilitate collaborative screening .

C: Collecting and Combining Data

Each review type will have different approaches for collecting and combining data, which involves pulling the relevant pieces of information out of the selected evidence. Refer back to the review question and the planned analysis when considering the variables that should be extracted from each study. Some review types (eg, systematic and scoping reviews) include extracting specific variables into forms or tables using a data extraction template. Other types of reviews (eg, state-of-the-art reviews) will use inductive or interpretive approaches to generate themes, codes, or other types of new data out of the texts of the included data sources. Regardless of the review type, the common aspect to this stage is distilling the primary data to the elements that will be used to answer the research question.

Pro Tip 5: Piloting the data extraction form with a handful of included studies will catch omissions in the data collection process and improve the inter-rater reliability of the project .

E: Explaining the Synthesis

At this stage, researchers will bring the results from the individual studies together for analysis and discuss what they have identified through the synthesis. While this step will look different for each review type, this process is a distinguishing feature of all knowledge synthesis work. Whether the synthesis process is quantitative, qualitative, conceptually guided, or some combination thereof, this step is what makes a review an actual form of knowledge synthesis. At this step, researchers transparently and systematically begin drawing together data from disparate sources to address the research question. Whatever form this synthesis may take, the important commonality is that the synthesis process itself is clearly explained and key decisions made by the team are explicitly described for the reader.

Pro Tip 6: For some review types, there are software options that can assist with analysis, such as RevMan for meta-analyses or qualitative data analysis software for qualitative analyses .

S: Summarizing the Findings

Once the findings have been synthesized and the review team is ready for dissemination, several factors need to be considered. In addition to the text, visualizations, such as figures and tables, are key for disseminating reviews. Pulling these parts into a coherent narrative, with key findings highlighted in engaging ways, promotes communication. Researchers should use the reporting standards for their specific review type as a guide when formatting their report into a manuscript for publication.

From our experience supporting hundreds of reviews, we have seen review teams thrive, struggle, and sometimes do both. The most successful review teams have a good plan, use expert advice and technological tools, and establish excellent communication practices. Like any research project, GME knowledge syntheses require a thorough understanding of the selected methods and a clear research question and target audience. Whether the goal is to change policy, develop new programs, or design better assessments, a well-conducted review can provide valuable evidence to support decisions.

Supplementary Material

- 1. Foster M, Jewell S. Assembling the Pieces of a Systematic Review A Guide for Librarians . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Harris JL, Booth A, Cargo M, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series—paper 2: methods for question formulation, searching, and protocol development for qualitative evidence synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol . 2018;97:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.023. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Hean S, Green C, Anderson E, et al. The contribution of theory to the design, delivery, and evaluation of interprofessional curricula: BEME Guide No. 49. Med Teach . 2018;40(6):542–558. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1432851. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Booth A, Carroll C. Systematic searching for theory to inform systematic reviews: is it feasible? Is it desirable? Health Info Libr J. 2015;32(3):220–235. doi: 10.1111/hir.12108. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Systematic Review Toolbox http//systematicreviewtoolscom/ Accessed November 5 . 2021.

- 6. Spencer AJ, Eldredge JD. Roles for librarians in systematic reviews: a scoping review. J Med Libr Assoc . 2018;106(1):46–56. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2018.82. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Morris M, Boruff JT, Gore GC. Scoping reviews: establishing the role of the librarian. J Med Libr Assoc . 2016;104(4):346–354. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.4.020. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Rethlefsen M, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev . 2021;10(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2 a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials BMJ. 2019. 366:l4898. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ]

- 10. Cook DA, Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education. Acad Med . 2015;90(8):1067–1076. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000786. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (94.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 6. Synthesize

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

Synthesis Visualization

Synthesis matrix example.

- 7. Write a Literature Review

- Synthesis Worksheet

About Synthesis

Approaches to synthesis.

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

How to Begin?

Read your sources carefully and find the main idea(s) of each source

Look for similarities in your sources – which sources are talking about the same main ideas? (for example, sources that discuss the historical background on your topic)

Use the worksheet (above) or synthesis matrix (below) to get organized

This work can be messy. Don't worry if you have to go through a few iterations of the worksheet or matrix as you work on your lit review!

Four Examples of Student Writing

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Click on the example to view the pdf.

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Next: 7. Write a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 12, 2024 11:48 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

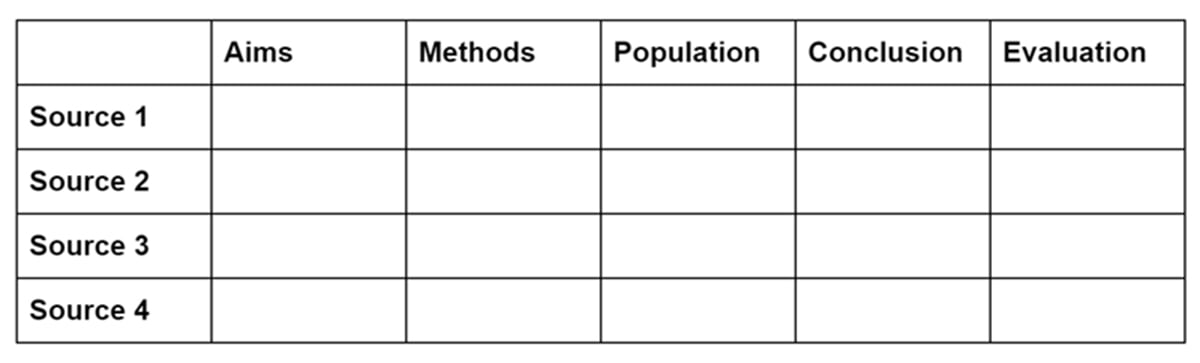

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

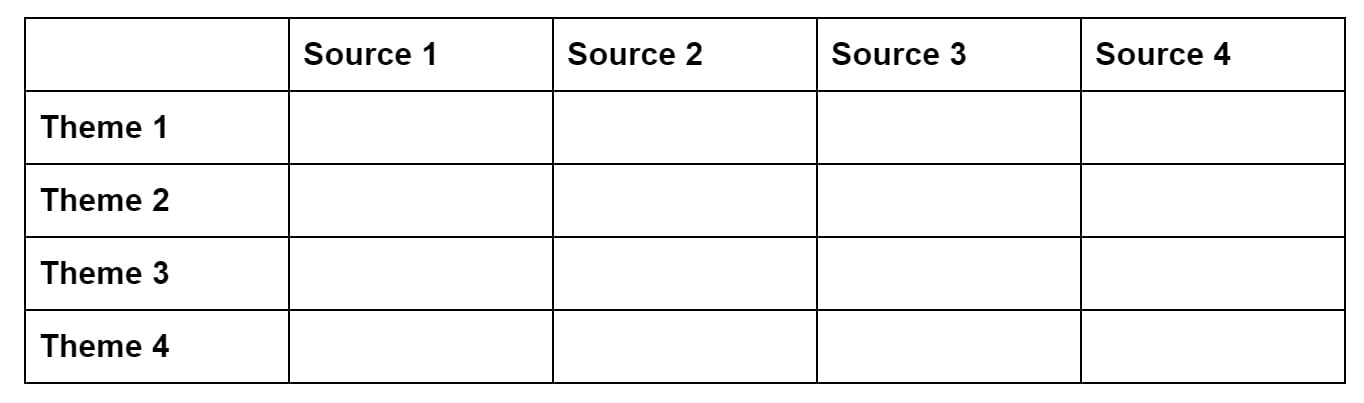

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

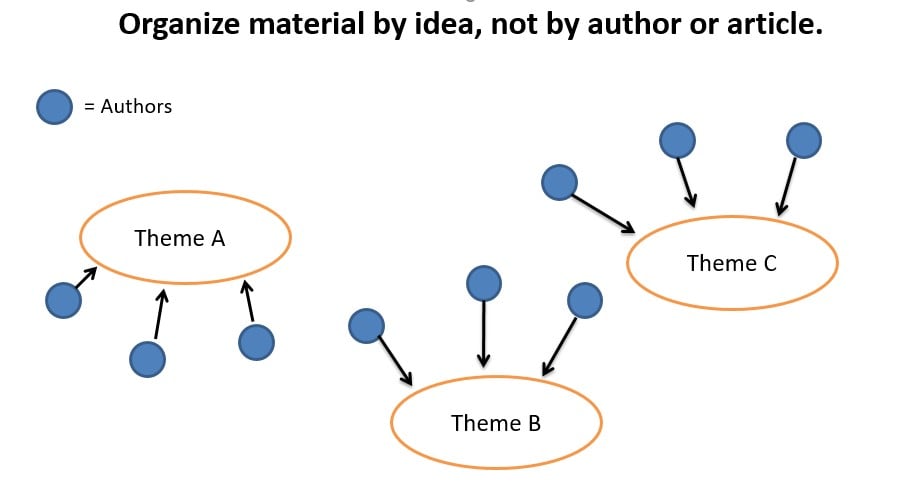

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

IMAGES

VIDEO