Case Study vs. Narrative Inquiry

What's the difference.

Case study and narrative inquiry are both qualitative research methods that involve in-depth exploration of a particular phenomenon or experience. However, they differ in their approach and focus. Case study typically involves the detailed examination of a single case or a small number of cases to understand a specific issue or problem. On the other hand, narrative inquiry focuses on collecting and analyzing stories or narratives from individuals to gain insight into their lived experiences and perspectives. While case study emphasizes the uniqueness and complexity of a particular case, narrative inquiry highlights the subjective and personal nature of storytelling. Both methods offer valuable insights and can be used to generate rich and detailed data for research purposes.

Further Detail

Case study and narrative inquiry are two research methodologies used in social sciences to investigate complex phenomena. Case study involves an in-depth analysis of a single case or multiple cases to understand a particular issue or problem. On the other hand, narrative inquiry focuses on collecting and analyzing stories or narratives to explore the experiences and perspectives of individuals.

Research Focus

Case study research typically focuses on a specific case or cases to gain insights into a particular phenomenon. Researchers may use various data collection methods such as interviews, observations, and document analysis to gather information about the case. In contrast, narrative inquiry is more concerned with understanding the lived experiences and subjective perspectives of individuals through the analysis of stories or narratives.

Data Collection

In case study research, data collection methods can vary depending on the research question and the nature of the case. Researchers may use a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques to gather information about the case. This can include interviews, surveys, observations, and document analysis. On the other hand, narrative inquiry relies primarily on collecting stories or narratives from participants through interviews, focus groups, or written accounts.

Data Analysis

Once data is collected in a case study, researchers analyze the information to identify patterns, themes, and relationships within the case. This analysis helps researchers draw conclusions and make recommendations based on the findings. In narrative inquiry, data analysis involves interpreting the stories or narratives collected from participants to uncover underlying meanings, themes, and perspectives. Researchers may use techniques such as thematic analysis or narrative analysis to analyze the data.

Research Design

Case study research often involves a detailed and systematic investigation of a single case or multiple cases over time. Researchers may use a holistic or embedded case study design to explore the complexities of the case. In contrast, narrative inquiry is more flexible in its research design, allowing researchers to adapt their approach based on the stories or narratives collected from participants. This can include a single narrative or multiple narratives depending on the research question.

Validity and Reliability

Validity and reliability are important considerations in both case study and narrative inquiry research. In case study research, researchers strive to ensure the validity and reliability of their findings by using multiple sources of data, triangulation, and member checking. Similarly, in narrative inquiry, researchers may enhance the validity and reliability of their findings by conducting member checks, peer debriefing, and maintaining an audit trail of the data analysis process.

Application

Case study research is commonly used in fields such as psychology, sociology, and education to investigate complex phenomena in real-world settings. Researchers may use case studies to explore individual behavior, organizational dynamics, or social issues. Narrative inquiry, on the other hand, is often used in fields such as anthropology, nursing, and communication to understand the lived experiences and perspectives of individuals through storytelling.

In conclusion, case study and narrative inquiry are two distinct research methodologies that offer unique approaches to investigating complex phenomena in social sciences. While case study research focuses on in-depth analysis of specific cases, narrative inquiry explores the subjective experiences and perspectives of individuals through storytelling. Both methodologies have their strengths and limitations, and researchers should carefully consider the research question and objectives when choosing between case study and narrative inquiry.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

1-647-261-6919

Difference Between Case Study And Narrative Research

- Success Team

- January 19, 2023

Transcribe, Translate, Analyze & Share

Join 170,000+ incredible people and teams saving 80% and more of their time and money. Rated 4.9 on G2 with the best AI video-to-text converter and AI audio-to-text converter , AI translation and analysis support for 100+ languages and dozens of file formats across audio, video and text.

Start your 7-day trial with 30 minutes of free transcription & AI analysis!

Research is an important part of any organization or business. There are two main types of research: case studies and narrative research. Both are valuable tools for gathering and analyzing information, but they have some important differences. Understanding the difference between case study and narrative research can help you select the best research method for your particular project.

What is Case Study Research?

Case study research is a type of qualitative research that focuses on a single case, or a small number of cases, to examine in depth. It seeks to understand a phenomenon by examining the context of the case and looking at the experiences, perspectives, and behavior of the people involved. Case study research is often used to explore complex social phenomena, such as poverty, health, education, and social change.

What is Narrative Research?

Narrative research is also a type of qualitative research that focuses on understanding how people make sense of their experiences. It involves collecting and analyzing stories, or narratives, from participants. These stories can be collected through interviews, focus groups, or other data collection techniques. By examining the stories in detail, researchers can gain insights into how people think about and make sense of the world around them.

Differences Between Case Study and Narrative Research

The most important differences between case study and narrative research are the focus and the type of data collected. Case studies focus on a single case or a small number of cases, while narrative research focuses on understanding how people make sense of their experiences. Case studies typically rely on quantitative data, such as surveys and measurements, while narrative research relies on qualitative data, such as interviews, stories, and observations.

Which is Better?

The answer to this question depends on the research question and the type of data needed to answer it. If the goal is to understand a single case in depth, then a case study is the best approach. If the goal is to understand how people make sense of their experiences, then narrative research is the best approach. In some cases, it may be beneficial to use a combination of both approaches.

Case study and narrative research are both valuable tools for gathering and analyzing information. Understanding the difference between the two can help you select the best research method for your particular project. While case studies are useful for understanding a single case in depth, narrative research is better for understanding how people make sense of their experiences. In some cases, it may be beneficial to use a combination of both approaches.

How To Use The Best Large Language Models For Research With Speak

Step 1: Create Your Speak Account

To start your transcription and analysis, you first need to create a Speak account . No worries, this is super easy to do!

Get a 7-day trial with 30 minutes of free English audio and video transcription included when you sign up for Speak.

To sign up for Speak and start using Speak Magic Prompts, visit the Speak app register page here .

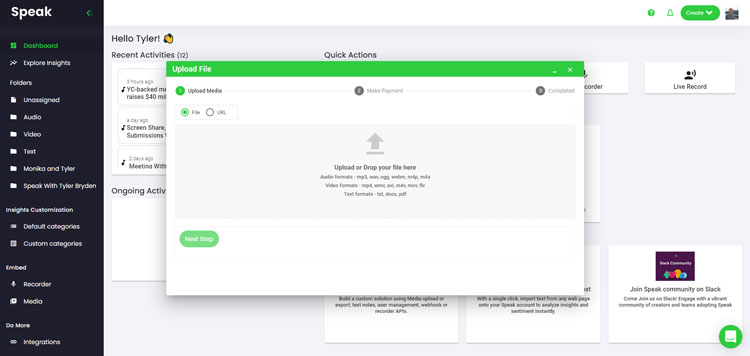

Step 2: Upload Your Research Data

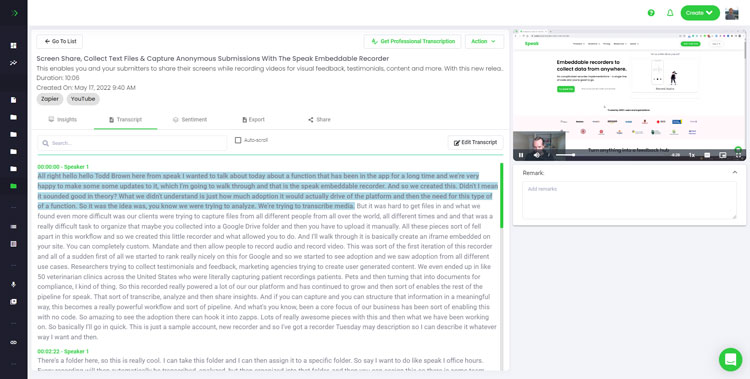

In Speak, you can seamlessly upload, transcribe, and translate audio, video, and text files all at once! If you have video, you can use our AI video-to-text converter to convert video to text; if you have audio, you can use our AI audio-to-text converter to convert audio to text. You can also transcribe YouTube videos and use AI to analyze text . You can see compatible file types for each option below.

Accepted Audio File Types

Accepted video file types, accepted text file types, csv imports.

You can also upload CSVs of text files or audio and video files. You can learn more about CSV uploads and download Speak-compatible CSVs here .

With the CSVs, you can upload anything from dozens of YouTube videos to thousands of Interview Data.

Publicly Available URLs

You can also upload media to Speak through a publicly available URL.

As long as the file type extension is available at the end of the URL you will have no problem importing your recording for automatic transcription and analysis.

YouTube URLs

Speak is compatible with YouTube videos. All you have to do is copy the URL of the YouTube video (for example, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qKfcLcHeivc ).

Speak will automatically find the file, calculate the length, and import the video.

If using YouTube videos, please make sure you use the full link and not the shortened YouTube snippet. Additionally, make sure you remove the channel name from the URL.

Speak Integrations

As mentioned, Speak also contains a range of integrations for Zoom , Zapier , Vimeo and more that will help you automatically transcribe your media.

This library of integrations continues to grow! Have a request? Feel encouraged to send us a message.

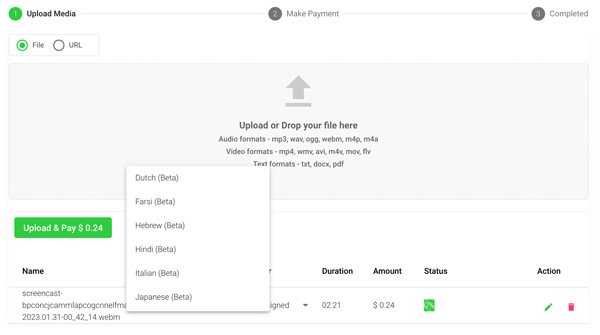

Step 3: Calculate and Pay the Total Automatically

Once you have your file(s) ready and load it into Speak, it will automatically calculate the total cost (you get 30 minutes of audio and video free in the 7-day trial – take advantage of it!).

If you are uploading text data into Speak, you do not currently have to pay any cost. Only the Speak Magic Prompts analysis would create a fee which will be detailed below.

Once you go over your 30 minutes or need to use Speak Magic Prompts, you can pay by subscribing to a personalized plan using our real-time calculator .

You can also add a balance or pay for uploads and analysis without a plan using your credit card .

Step 4: Wait for Speak to Analyze Your Research Data

If you are uploading audio and video, our automated transcription software will prepare your transcript quickly. Once completed, you will get an email notification that your transcript is complete. That email will contain a link back to the file so you can access the interactive media player with the transcript, analysis, and export formats ready for you.

If you are importing CSVs or uploading text files Speak will generally analyze the information much more quickly.

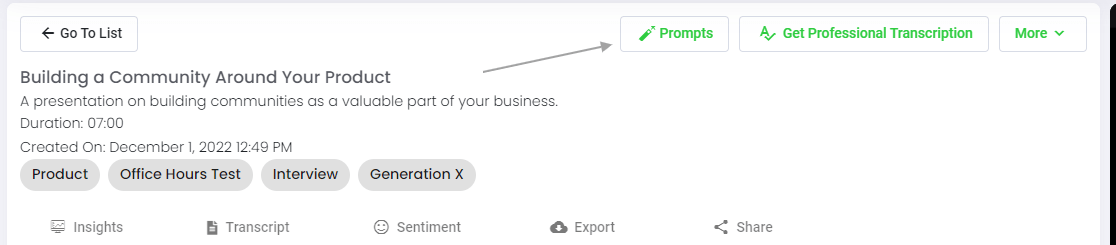

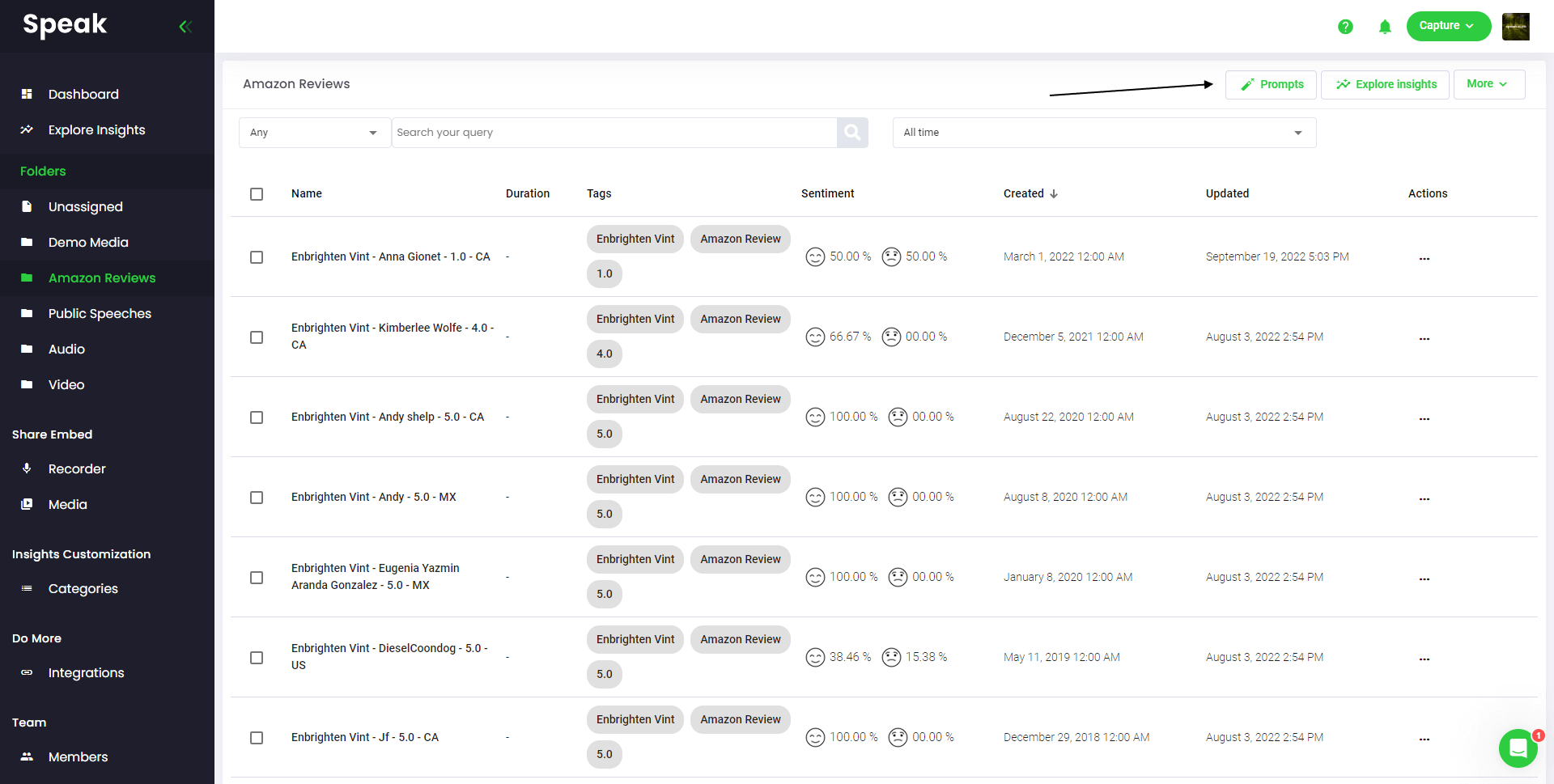

Step 5: Visit Your File Or Folder

Speak is capable of analyzing both individual files and entire folders of data.

When you are viewing any individual file in Speak, all you have to do is click on the “Prompts” button.

If you want to analyze many files, all you have to do is add the files you want to analyze into a folder within Speak.

You can do that by adding new files into Speak or you can organize your current files into your desired folder with the software’s easy editing functionality.

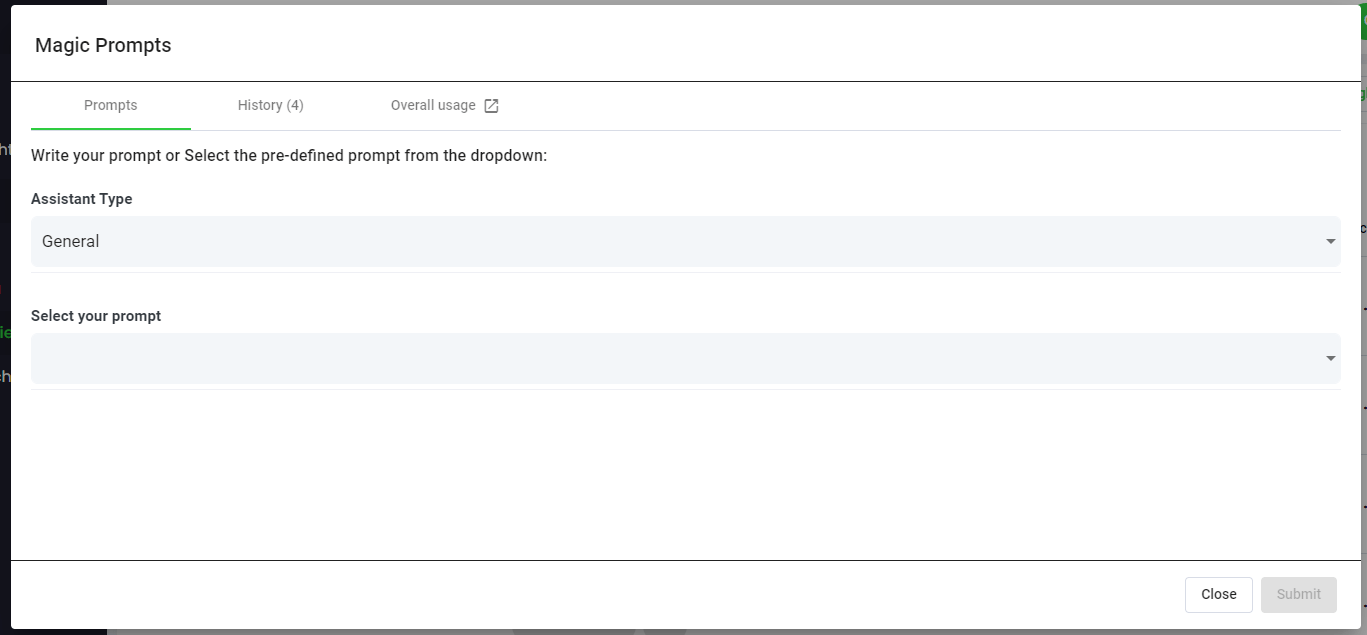

Step 6: Select Speak Magic Prompts To Analyze Your Research Data

What are magic prompts.

Speak Magic Prompts leverage innovation in artificial intelligence models often referred to as “generative AI”.

These models have analyzed huge amounts of data from across the internet to gain an understanding of language.

With that understanding, these “large language models” are capable of performing mind-bending tasks!

With Speak Magic Prompts, you can now perform those tasks on the audio, video and text data in your Speak account.

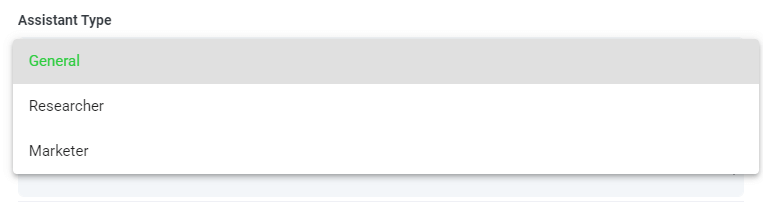

Step 7: Select Your Assistant Type

To help you get better results from Speak Magic Prompts, Speak has introduced “Assistant Type”.

These assistant types pre-set and provide context to the prompt engine for more concise, meaningful outputs based on your needs.

To begin, we have included:

Choose the most relevant assistant type from the dropdown.

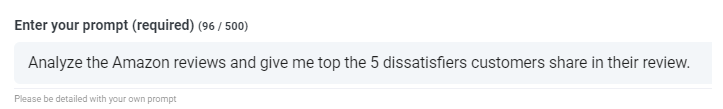

Step 8: Create Or Select Your Desired Prompt

Here are some examples prompts that you can apply to any file right now:

- Create a SWOT Analysis

- Give me the top action items

- Create a bullet point list summary

- Tell me the key issues that were left unresolved

- Tell me what questions were asked

- Create Your Own Custom Prompts

A modal will pop up so you can use the suggested prompts we shared above to instantly and magically get your answers.

If you have your own prompts you want to create, select “Custom Prompt” from the dropdown and another text box will open where you can ask anything you want of your data!

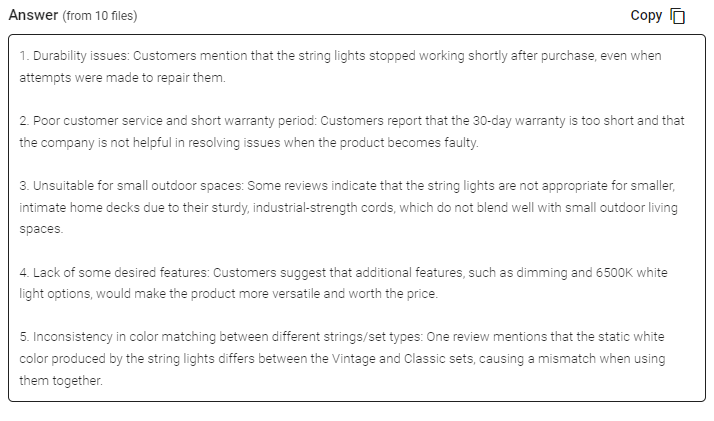

Step 9: Review & Share Responses

Speak will generate a concise response for you in a text box below the prompt selection dropdown.

In this example, we ask to analyze all the Interview Data in the folder at once for the top product dissatisfiers.

You can easily copy that response for your presentations, content, emails, team members and more!

Speak Magic Prompts As ChatGPT For Research Data Pricing

Our team at Speak Ai continues to optimize the pricing for Magic Prompts and Speak as a whole.

Right now, anyone in the 7-day trial of Speak gets 100,000 characters included in their account.

If you need more characters, you can easily include Speak Magic Prompts in your plan when you create a subscription.

You can also upgrade the number of characters in your account if you already have a subscription.

Both options are available on the subscription page .

Alternatively, you can use Speak Magic Prompts by adding a balance to your account. The balance will be used as you analyze characters.

Completely Personalize Your Plan 📝

Here at Speak, we’ve made it incredibly easy to personalize your subscription.

Once you sign-up, just visit our custom plan builder and select the media volume, team size, and features you want to get a plan that fits your needs.

No more rigid plans. Upgrade, downgrade or cancel at any time.

Claim Your Special Offer 🎁

When you subscribe, you will also get a free premium add-on for three months!

That means you save up to $50 USD per month and $150 USD in total.

Once you subscribe to a plan, all you have to do is send us a live chat with your selected premium add-on from the list below:

- Premium Export Options (Word, CSV & More)

- Custom Categories & Insights

- Bulk Editing & Data Organization

- Recorder Customization (Branding, Input & More)

- Media Player Customization

- Shareable Media Libraries

We will put the add-on live in your account free of charge!

What are you waiting for?

Refer Others & Earn Real Money 💸

If you have friends, peers and followers interested in using our platform, you can earn real monthly money.

You will get paid a percentage of all sales whether the customers you refer to pay for a plan, automatically transcribe media or leverage professional transcription services.

Use this link to become an official Speak affiliate.

Check Out Our Dedicated Resources📚

- Speak Ai YouTube Channel

- Guide To Building Your Perfect Speak Plan

Book A Free Implementation Session 🤝

It would be an honour to personally jump on an introductory call with you to make sure you are set up for success.

Just use our Calendly link to find a time that works well for you. We look forward to meeting you!

Trusted by 150,000+ incredible people and teams

Get 93% Off With Speak's Year-End Deal 🎁🤯

For a limited time, save 93% on a fully loaded Speak plan. Start 2025 strong with a top-rated AI platform.

Qualitative Research in Corporate Communication

A blogs@baruch site, chapter 4: five qualitative approaches to inquiry.

In this chapter Creswell guides novice researchers (us) as we work through the early stages of selecting a qualitative research approach. The text outlines the origins, uses, features, procedures and potential challenges of each approach and provides a great overview. Why identify our approach to qualitative inquiry now? To offer a way of organizing our ideas and to ground them in the scholarly literature (69). The author includes a chart on page 104 that provides a convenient comparison of major features.

The 5 approaches are NARRATIVE RESEARCH, PHENOMENOLOGY, GROUNDED RESEARCH, ETHNOGRAPHY, and CASE STUDY.

NARRATIVE RESEARCH

In contrast to the other approaches, narrative can be a research method or an area of study in and of itself. Creswell focuses on the former, and defines it as a study of experiences “as expressed in lived and told stories of individuals” (70). This approach emerged out of a literary, storytelling tradition and has been used in many social science disciplines.

Narrative researchers collect stories, documents, and group conversations about the lived and told experiences of one or two individuals. They record the stories using interview, observation, documents and images and then report the experiences and chronologically order the meaning of those experiences. Other defining features are available on p. 72.

These are the primary types of narrative:

- Biographical study, writing and recording the experiences of another person’s life.

- Autoethnography, in which the writing and recording is done by the subject of the study (e.g., in a journal).

- Life history, portraying one person’s entire life.

- Oral history, reflections of events, their causes and effects.

For all of the research approaches, Creswell first recommends determining if the particular approach is an appropriate tool for your research question. In this case, narrative research methodology doesn’t follow a rigid process but is described as informal gathering of data.

The author provides recommendations for methodologies on pps 74-76 and introduces two interesting concepts unique to narrative research: 1) Restorying is the process of gathering stories, analyzing them for key elements, then rewriting (restorying) to position them within a chronological sequence. 2) Creswell describes a collaboration that occurs between participants and researchers during the collection of stories in which both gain valuable life insight as a result of the process.

Narrative research involves collecting extensive information from participants; this is its primary challenge. But ethical issues surrounding the stories may present weightier difficulties, such as questions of the story’s ownership, how to handle varied impressions of its veracity, and managing conflicting information. For further reading on the activities of narrative researchers Creswell recommends Clandinin and Connelly’s Narrative Inquiry (2000).

PHENOMENOLOGY

Phenomenology is a way to study an idea or concept that holds a common meaning for a small group (3-15) of individuals. The approach centers around lived experiences of a particular phenomenon, such as grief, and guides researchers to distill individual experiences to an essential concept. Phenomenological research generally hones in on a single concept or idea in a narrow setting such as “professional growth” or “caring relationship.”

The evolution of phenomenology from its philosophical roots with Heidegger’s and Sartre’s writing often emerges in current researchers’ exploration of the ideas (77). In contrast to the other four approaches, phenomenology’s tradition is important for establishing themes in the data. In addition to its relationship to philosophy, another key phenomenology feature is bracketing, a process by which the researcher identifies and sets aside any personal experience with the phenomena under study (78).

Phenomenology has two main subsets. Hermeneutic, by which a researcher first follows his/her own abiding concern or interest in a phenomenon; then reflects upon the essential themes that constitute the nature of this lived experience; describex the phenomenon; crafts an interpretation and finally mediates the different resultant meanings. The second type, transcendental, is more empirical and focused on a data analysis method outlined on page 80.

Cresswell favors a systematic methodology outlined by Moustakas (1994) in which participants are asked two broad, general questions: 1) What have you experienced in terms of the phenomenon? 2) What context of situations have typically influenced your experiences of the phenomenon? For some researchers, the author believes phenomenology may be too structured. He also mentions the additional challenge of identifying a sample of participants who share the same phenomenon experience.

Creswell recommends two sources for further reading on phenomenology: Moustakas’s Phenomenological Research Methods (1994) and van Manen’s Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy (1990).

GROUNDED THEORY RESEARCH

Grounded theory seeks to generate or discover a theory-a general explanation– for a social process, action or interaction shaped by the views of participants (p. 83). One key factor in grounded theory is that it does not come “off the shelf” but is “grounded” from data collected from a large sample. Creswell recommends an approach to this qualitative research prescribed by Corbin & Strauss (2007).

The author describes several defining features of grounded theory research (85). The first is that it focuses on a process or actions that has “movement” over time. Two examples of processes provided include the development of a general education program or “supporting faculty become good researchers.” An important aspect of data collection in this research is “memoing.” In which the researcher “writes down ideas as data are collected and analyzed,” usually from interviews.

Data collection is best be described as a “zigzag” process of going out to the field to gather information and then back to the office to analyze it and back out to the field. The author discusses various ways of coding the information into major categories of information (p. 86).

Another approach to grounded theory is that of Charmaz (2006). Creswell notes that Charmaz “places more emphasis on the views, values, belief, feelings, assumptions and ideologies of individuals than on the methods of research.” (p. 87)

The author states that this is a good design to use when there isn’t a theory available to “explain or understand a process.” (p. 88). Creswell further notes that the research question will focus on “understanding how individuals experience the process and identify steps in the process” that can often involve 20 to 60 interviews.

Some challenges in using this design is that the researcher must set aside “theoretical ideas or notions so that the analytic, substantive theory can emerge.” (p. 89) It is also important that the researcher understand that the primary outcome of this research is a “theory with specific components: a central phenomenon, causal conditions, strategies, conditions and context, and consequences,” according to Corbin & Strauss’ (p. 90). However, if a researcher wants a less structured approach the Charmaz (2006) method is recommended.

ETHNOGRAPHIC RESEARCH

Ethnography is a qualitative research design in which the unit of analysis is typically greater than 20 participants and focuses on an “entire culture-sharing group.” (Harris, 1968). In this approach, the “research describes and interprets the shared and learned patterns of values, behaviors, beliefs, and language” of the group. The method involves extended observations through “participant observation, in which the researcher is immersed in the day-to-day lives of the people and observes and interviews the group participants.” (p. 90).

Creswell notes that there is a lack of orthodoxy in ethnographic research with many pluralistic approaches. He lists a number of other researchers (p.91) but states that he draws on Fetterman’s (2009) and Wolcott’s (2008a) approaches in this text.

Some defining features of ethnographic research are listed on pages 91 and 92. They include that: it “focuses on developing a complex, complete description of the culture of a group, a culture-sharing group;” that ethnography however “is not the study of a culture, but a study of the social behaviors of an identifiable group of people;” that the group “has been intact and interacting for long enough to develop discernable working patterns,” and that ethnographers start with a theory drawn from “cognitive science to understand belief and ideas” or materialist theories (Marxism, acculturation, innovation, etc.)

Some types of ethnographies include “confessional ethnography, life history, autoethnography, feminist ethnography, visual ethnography,”etc., however, Creswell emphasizes two popular forms. The first is the realist ethnography-used by cultural anthropologists, it is “an objective account of a situation, typically written in the third-person point of view and reporting objectively on the information learned from participants.” (p. 93). The second is the critical ethnography in which the author advocates for groups marginalized in society (Thomas, 1993). This type of research is typically conducted by “politically minded individuals who seek through their research, to speak out against inequality and domination” (Carspecken & Apple, 1992). (p. 94).

The procedures for conducting an ethnography are listed on p. 94-96. One key element in these procedures is the gathering of information where the group works or lives through fieldwork (Wolcott, 2008a); and respecting the daily lives of these individuals at the site of study. Some key challenges in this type of research are that one must have an “understanding of cultural anthropology, the meaning of a social-cultural system, and the concepts typically explored by those studying cultures. Also, data collection requires a lot of time on the field. (p. 96)

CASE STUDY RESEARCH

In case study research, defined as the “the study of a case within a real-life contemporary context or setting” Creswell takes the perspective that such research “is a methodology: a type of design in qualitative research that may be an object of study, as well as a product of inquiry.” Further, case studies have bounded systems, are detailed and use multiple sources of information (p. 97). Creswell references the work of Stake (1995) and Yin (2009) because of their systematic handling of the subject.

The author draws attention to several features of the case study approach, but emphasizes a critical element “is to define a case that can be bounded or described within certain parameters, such as a specific place and time.” Other components of the research method include its intent-which may take the form of intrinsic case study or instrumental case study (p. 98); its reliance on in-depth understanding; and its utilization of case descriptions, themes or specific situations. Finally, researchers typically conclude case studies with “assertions” from their learning (p. 99).

The text touches on several types of case studies that can be differentiated by size, activity or intent and that can involve single or multiple cases (p.99). In instances of collective case study design where the researcher may use multiple case studies to examine one issue, the text recommends Yin (2009) logic of replication be used. Creswell goes on to point out that if the researcher wishes to generalize from findings, care needs to be taken to select representative cases. This could be useful, time-saving information for class members considering this method.

In outlining procedures for conducting a case study (p.100), Creswell recommends “that investigators first consider what type of case study is most promising and useful” and advocates cases that show different perspectives on a problem, process or event.” Data analysis can be holistic (considering the entire case) or embedded (using specific aspects of the case).

Some of the challenges of case study research are determining the scope of the research and deciding on the bounded system and determining whether to study the case itself or how the case illustrates an issue. In the instance of multiple cases, the author makes the somewhat counter intuitive assertion that “the study of more than one case dilutes the overall analysis” (p. 101).

THE FIVE APPROACHES COMPARED

Creswell gives an overview of the commonality of the five research methods (p. 102) before explaining key differences among more similar seeming types of research, e.g. narrative research, ethnography. Here the author underlines that “the types of data one would collect and analyze would differ considerably.” He uses the example of the study of a single individual to make his argument, recommending narrative research instead of ethnography, which has a broader scope and case study, which may involve multiple cases.

In considering differences, Creswell puts forth that the research methods accomplish divergent goals, have different origins and employ distinct methods of analyzing data – the author underlines the data analysis stage as being the most exaggerated point of difference (p. 103). The final product, “the result of each approach, the written report, takes shape from all the processes before it.

In Table 4.1 (p. 104) Creswell provides a framework table that contrasts the characteristics of the five qualitative approaches. Given its stated suitability for both “journal-article length study” and dissertation or book-length work, class members may find it a handy reference for the mini study assignment and beyond.

Tricia Chambers, Eric Lugo, Kathryn Lineberger

8 thoughts on “ CHAPTER 4: Five Qualitative Approaches to Inquiry ”

I plan to use Narrative Research in my paper. It would be nice if I can know some recording skills of group conversation. I agree, Hui! There were none detailed in this chapter though. ~KL Haha, guess I can get some from google then.

For the mini-study, I’m hoping to use narrative research. Initially, I was planning on it as well as content analysis for my thesis in the fall, but after reading this chapter, I have some more work to do! Phenomenology or grounded theory might be better suited for what I want to accomplish. Needless to say, this chapter review got me thinking!

It seems to me that my area of interest might be carried out best with an ethnographic study. Since I want to look at communicators in the performing arts industry, I think that fits the description of a culture sharing group. The method also seems to fit what I would hope to do for my study, observe participants in their workplace and conduct interviews.

However, I would like to look more into the idea of overlapping approaches because I think it would also be interesting to look at specific PR campaigns or marketing campaigns carried out by my participants and this would likely fall under the case-study approach.

This chapter is definitely most useful for the initial phase of the research paper. For my research, I want to look into understanding consumer behavior and specific aspects of a company’s behavior/marketing tactics (maybe CSR) that affects its brand perception (using Dole Food Company). In taking this direction for my study, I think I’m stuck somewhere between phenomenology or ethnographic research.

I think my research might align more with phenomenography, because I don’t know if I’ll exactly be looking into any specific subcultures as ethnographic research does.

This chapter definitely got me thinking about what I’d like to accomplish with my mini-study and later on my thesis. What I’ve been exposed to the most in the corporate communications program are case studies because they’re part of learning. Logically it seems that Phenomenology or Ethnographic research is where my research idea will lead me, but I’m still in the phase of getting a refined research question of out my bigger ideas. At least now I know the routes I can go.

I would like to know if the five categories of the attributes related to illness representation were defined through the research, or beforehand? You mention the researchers were able to use these attributes to formulate their hypothesis and I was wondering if it was defined by them then how would this effect results because I think I want to define some factors myself, but I don’t want to introduce any bias? Should I even worry about this?

Hi Sheena, you might ask the Chapter 5 team about this. ~KL

That was a great break down of the different types of studies presented in the book. This was very helpful to me as I was unsure of what type of study I was going to do, but after reading this summary I have a much better idea. I want to study putting loved ones in a nursing home versus seeking out home-based alternatives, and I think a phenomenological study is where I am leaning towards.

I feel strongly pulled to the phenomenological framework, even though it’s definition is causing me the most confusion! I Anti-corporate sentiment is a human experience, and I think it would be interesting to find a small group of anarchists or anti-capitalists or just young people who participated in the Occupy movement and understand their concept of this phenomena.

I will need to determine whether a phenomenological study allows for methods interpretation outside interviews or focus groups. I feel that much of what I am studying is a phenomenon perpetuated by the media, and I would like to incorporate content analysis and document research into my analysis.

Comments are closed.

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

Subject index

"`Not so much a handbook, but an excellent source of reference' - British Journal of Social Work This volume is the definitive resource for anyone doing research in social work. It details both quantitative and qualitative methods and data collection, as well as suggesting the methods appropriate to particular types of studies. It also covers issues such as ethics, gender and ethnicity, and offers advice on how to write up and present your research."

Narrative Case Studies

- By: JERROLD R. BRANDELL & THEODORE VARKAS

- In: The Handbook of Social Work Research Methods

- Chapter DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781412986182.n16

- Subject: Social Work

- Keywords: fathers ; mothers ; parenting ; parents ; trauma

- Show page numbers Hide page numbers

The narrative case study is a research instrument that is used for the in-depth study of various social and clinical problems, to understand stages or phases in processes, and to investigate a phenomenon within its environmental context (Gilgun, 1994). The case study method, which has been termed “the only possible way of obtaining the granite blocks of data on which to build a science of human nature” (Murray, 1955, p. 15), has been used in fields such as clinical psychoanalysis, human behavior theory, and Piagetian cognitive development theory. Case studies also have been used to advantage in diverse professions such as medicine, law, and business, where they hold a time-honored role in both research and teaching (Gilgun, 1994). One popular writer, the neurologist Oliver Sacks, has received critical acclaim for his richly detailed and compelling case studies of patients with various types of brain diseases and syndromes, ranging from postencephalitis to autism. In its simplest form, the case study is a story told for the purpose of understanding and learning. It captures essential meanings and qualities that might not be conveyed as forcefully or as effectively through other research media. Fundamentally, the narrative case study provides entrée to information that might otherwise be inaccessible. It makes possible [Page 294] the capture of phenomena that might not be understood as readily through other means of study.

The narrative case study has been a tradition in social work that spans several generations of social work theorists. Authors such as Mary Richmond, Annette Garrett, Helen Harris Perlman, Florence Hollis, and Selma Fraiberg have, inter alia, used case exemplars to illustrate a range of issues and problems in diagnosis and intervention. Case studies continue to hold a prominent role in the dissemination of clinical knowledge in social work education. Although somewhat less common today, the use of casebooks to augment textual and other didactic materials in the clinical instruction of social work graduate students historically was a common practice. Spence (1993) observes that the traditional case report remains the “most compelling means of communicating clinical findings, and the excitement attached to both reading and writing case histories has lost none of its appeal” (p. 37). The value of the case study, it might be argued, lies in its experience-near descriptions of clinical processes. Such descriptions are phenomenologically distinctive and permit the student to identify with the experience of the worker and the reality of the clinical encounter, albeit vicariously. Case studies provide examples of what already has been encountered and how difficult situations were handled. Narrative case studies have been used extensively in several different social work literatures including child and family welfare, family therapy, individual therapy, group work, cross-cultural studies, and practice evaluations.

The Case Study Defined

The narrative case study is defined as the intensive examination of an individual unit, although such units are not limited to individual persons. Families, treatment teams, clinical interview segments, and even whole communities are legitimate units for investigation (Gilgun, 1994). It also can be argued that a defining characteristic of the case study in social work is its focus on environmental context, although certain exceptions may exist (e.g., single-case experimental research designs, where context is either not emphasized or deemed to be irrelevant). Case studies are held to be idiographic (which means that the unit of study is the single unit); multiple variables are investigated; and generalization is fundamentally analytic, inferential, and impressionistic rather than statistical and probabilistic. When generalization takes this form, the findings extrapolated from a single case subsequently are compared for “goodness of fit” with other cases and/or patterns predicted by extant theory or prior research (Gilgun, 1994). Nomothetic research, by contrast, systematically investigates a few variables using groups of subjects rather than individual units. Nomothetic [Page 295] research, currently the dominant mode of investigation in the social and behavioral sciences, attempts to distill general laws from its findings. Large probability samples are especially valued inasmuch as they permit the use of powerful statistics. These, in turn, strengthen the claim of probabilistic generalizability (Gilgun, 1994).

Postmodernism and the Narrative Case Study

Although many journals in social work continue to place an emphasis on nomothetic research, clinical social work, psychology, and other human services appear to be in a transitional period where basic assumptions about what constitutes science and scientific inquiry are being challenged. The positivist worldview, which has exerted a powerful and pervasive influence on modern scientific thought, also has imposed significant restraints on the nature of research within the clinical professions (Howard, 1985; Mahoney, 1991; Niemeyer, 1993; Polkinghorne, 1988). As theorists have become increasingly aware of such restrictions, efforts to cultivate and distill methods of investigation that are less bound by the assumptions of positivist science have increased (Niemeyer, 1993). Consequently, clinical scholars have begun to consider issues or approaches such as self-agency, hermeneutics, semiotics, and theories that emphasize intentional action and narrative knowing. Anderson (1990) even goes so far as to declare, “We are seeing in our lifetimes the collapse of the objectivist worldview that dominated the modern era” and that it is being supplanted by a constructivist worldview (p. 268). This position seems rather extreme, although there clearly has been a sustained transdisciplinary interest in constructivism over the past 20 years or so. The common assumption shared by all constructivist orientations has been described in the following manner: No one has access to a singular, stable, and fully knowable reality. All of our understandings, instead, are imbedded in social and interpersonal contexts and are, therefore, limited in perspective, depth, and scope. Constructivist approaches appear to have a common guiding premise that informs all thinking about the nature of knowing. In effect, constructivist thinking assumes that all humans (a) are naturally and actively engaged in efforts to understand the totality of their experiences in the world, (b) are not able to gain direct access to external realities, and (c) are continually evolving and changing (Niemeyer, 1993). Therefore, constructivism and the study of case narratives are the study of meaning making. As social workers and as humans, we are compelled to interpret experience, to search for purpose, and to understand the significance of events and scenarios in which we play a part. Although incompatible with the aims of nomothetic [Page 296] research investigation, the narrative case study might prove to be especially well suited for the requirements of a postmodern era.

Limitations of the Narrative Case Study

Several significant limitations of the narrative case study have been identified in both the clinical social work and psychoanalytic literatures. One of these is the heavy reliance placed on anecdote and narrative persuasion in typical case studies, where a favored or singular explanation is provided (Spence, 1993). In effect, the story that is being told often has but one ending. In fact, the narrative case study might “function best when all the evidence has been accounted for and no other explanation is possible” (Spence, 1993, p. 38). Spence (1993) also believes that the facts presented in typical case studies almost invariably are presented in a positivist frame. In other words, a somewhat artificial separation occurs between the observer/narrator and the observed. Although clinical realities are inherently ambiguous and subject to the rule of multideterminism (a construct in which any psychic event or aspect of behavior can be caused my multiple factors and may serve more than one purpose in the psychic framework and economy [Moore & Fine, 1990, p. 123]), “facts” in the case narrative are presented in such a manner as to lead the reader to a particular and, one might argue, inevitable solution.

Another criticism of the narrative case study has been what Spence (1993) terms the “tradition of argument by authority.” The case narrative has a “closed texture” that coerces the reader into accepting at face value whatever conclusions the narrator himself or herself already has made about the case. Disagreement and alternative explanations often are not possible due to the fact that only the narrator has access to all of the facts and tends to report these selectively. In Spence's view, this “privileged withholding” occurs for two interrelated reasons: (a) the narrator's need to protect the client's confidentiality by omitting or altering certain types of information and (b) the narrator's unintended or unconscious errors of distortion, omission, or commission. The effect, however, is that the whole story is not told. Sigmund Freud, whose detailed case studies of patients with obsessive-compulsive, phobic, hysterical, and paranoid disorders are recognized as exemplars of the psychoanalytic method, appears to have anticipated this limitation. Freud (1913/1958) remarked, “I once treated a high official who was bound by his oath of office not to communicate certain things because they were state secrets, and the analysis came to grief as a consequence of this restriction.” Freud reasoned,

The whole task becomes impossible if a reservation is allowed at any single place. But we have only to reflect what would happen if the right of asylum existed at any point in a town; [Page 297] how long would it be before all the riff-raff of the town had collected there? (p. 136, as cited in Spence, 1993)

Using the Narrative Case Study as a Qualitative Research Tool

Although some authors have observed that case studies are not limited to qualitative research applications, the basic focus in the remainder of this chapter is on the narrative case study in the context of qualitative research. The case study allows for the integration of theoretical perspective, intervention, and outcome. In an effort to establish a link between a unique clinical phenomenon and its context where one might not be immediately evident, the case study can be used to hypothesize some type of cause and effect. In clinical work, case studies often are the only means by which to gain entrée to various dimensions of therapeutic process and of certain hypothesized aspects of the complex treatment relationship between the social worker and the client (e.g., the transference-countertransference axis). The dissemination of such data thus becomes an important method both for theory building and as a vehicle for challenging certain assumptions about treatment process, diagnosis, and the therapeutic relationship, inter alia. Despite the limitations noted earlier and the fact that there appears to be little uniformity in the structure of published case studies, the narrative case study, nevertheless, continues to make significant (some would argue seminal) contributions to social work practice theory and clinical methods.

Guidelines for Determining Goodness of Fit

It first must be determined whether the narrative case study is the most appropriate research tool for the theme or issue that is being explored. Narrative case studies should be written so that it is possible to make useful generalizations. It should be possible to use the case study as the basis for additional research, an important point that argues against the closed texture issue identified by Spence (1993). For example, in hypothesizing that a particular variable or a specific sequence of events is responsible for a particular outcome, the structure of the case study should permit the subsequent testing of such a hypothesis via additional qualitative or quantitative means.

One might consider the case of a man who has developed a fear of riding in cars following an automobile accident in which another motorist was killed. In his case, he eventually becomes fearful not only of riding in cars but also of being near streets or, perhaps, even of seeing films of others riding in cars. These, as well as other phenomena associated with automobiles and accidents, eventually lead to states of nearly incapacitating anxiety. The clinician might hypothesize that, following a traumatic experience such as a serious automobile accident, the development of acute [Page 298] anxiety might not be limited solely to driving in cars but might extend or generalize to other, nominally more benign stimuli (e.g., pictures of cars, engine sounds). One might design another study to determine the statistical probability of developing such symptomatology following a serious auto accident by interviewing a large sample of accident victims to determine how similar their experiences were. However, suppose that in our case, the man developed not only a fear of cars and associated phenomena but also a fear of leaving his house or of being around unfamiliar people. This might be somewhat more difficult to explain without obtaining additional data. One might wish to have further information regarding whether there is a history of emotional problems or other traumata predating the most recent traumatic experience, the individual's physical health status, current or past use of drugs and/or alcohol, and quality of current interpersonal relationships including those with family members. It also might be helpful to have more remote data such as early life history and history of losses. In effect, as more variables are added to the equation, the narrative case study becomes that much more attractive as a basic research instrument, uniquely equipped to identify an extensive range of variables of interest.

In such an instance, the narrative case study permits the researcher to “capture” exceedingly complex case situations, allowing for a considerable degree of detail and richness of understanding. Elements of the recent and remote past can be interwoven with particular issues in the present, thereby creating a rich tapestry and an equally sound basis for additional investigation. In fact, the narrative case study is especially useful when complex dynamics and multiple variables produce unusual or even rare situations that might be less amenable to other types of research investigations.

Specific Guidelines for Practice Utilization

One very common type of case study is chronological in nature, describing events as they occur over a period of time. Making inferences about causality, or about the linkage between events and particular sequelae, may be enhanced by the use of such an organizing framework. A second type of structure for organizing the narrative case study is the comparative structure , in which more than a single commentary is provided for the case data. Such an organizing framework may be a method for combating the problem of the narrator's tendency to arrive at a singular explanation for the clinical facts and their meaning.

One somewhat more complex sequence for the structure of the narrative case study might consist of the following components: (a) identification of the issue, problem, or process being studied; (b) review of relevant prior literature; (c) identification of methods used for data collection such as written process notes, progress notes, other clinical documentation, archival records, client interviews, direct observation, [Page 299] and participant observation; (d) description of findings from data that have been collected and analyzed; and (e) development of conclusions and implications for further study.

Certainly, other frameworks also exist inasmuch as case studies are heterogeneous, and serve a variety of purposes Runyan (1982) observes that case studies may be descriptive, explanatory, predictive, generative, or used for hypothesis testing. Furthermore, case narratives may be presented atheoretically or within the framework of particular developmental or clinical theory bases.

Clinical Case Illustration

The case study method was selected in this instance for two reasons. First, this case was deemed by the therapist (the first author) to have a highly unusual and complex clinical profile. Second, there is a paucity of clinical and theoretical literature focusing generally on countertransference issues and reactions in the treatment of children and adolescents. The case is described in the first person by the first author (for a more detailed discussion of this case, see Brandell, 1999).

Dirk was not quite 20 years old when he first requested treatment at a family service agency for long-standing insomnia and a “negative outlook on life.” He often felt as though he might “explode,” and he suffered from chronic anxiety that was particularly pronounced in social situations. He reluctantly alluded to a family “situation” that had exerted a dramatic and profound impact on his life, and as the early phase of his treatment began to unfold, the following account gradually emerged. When Dirk was perhaps 13 years of age, his father (who shall be referred to as Mr. S.) was diagnosed with cancer of the prostate. Unfortunately, neither parent chose to reveal this illness to Dirk, his two older brothers, or his younger sister for nearly 1½ years. Mr. S., an outdoorsman who had been moderately successful as a real estate developer and an entrepreneur, initially refused treatment, and his condition gradually worsened. By the time he finally consented to surgery some 18 months later, the cancer had metastasized and his prognosis was terminal. A prostatectomy left him impotent, increasing the strain in a marriage that already had begun to deteriorate.

Within several months of his father's surgery, when Dirk was perhaps 14 or 15 years old, Ms. S. (Dirk's mother) began a clandestine affair with a middle-aged man who resided nearby. The affair intensified, and presumably as a consequence of Ms. S.'s carelessness, Mr. S. learned of the affair. He also learned that she was planning a trip around the world with her lover. Although narcissistically mortified and enraged, he chose not to confront his wife right away, instead plotting secretly to murder her. On a weekday morning when Dirk and his younger sister were at school (his older brothers no longer resided in the family home), Mr. S. killed his wife in their [Page 300] bedroom with one of his hunting rifles. He then carefully wrapped her body up, packed it in the trunk of the family car, and drove to a shopping center, where he took his own life. The news was, of course, devastating to Dirk and his siblings, and it was made even more injurious due to the relentless media coverage that the crime received. Every conceivable detail of the murder-suicide was described on television and in the local press. Suddenly, Dirk and his siblings were completely bereft of privacy. Nor was there any adult intercessor to step forward and protect them from the continuing public exposure, humiliation, and pain.

These traumatic injuries were compounded by the reactions of neighbors and even former family friends, whose cool reactions to Dirk and his siblings bordered on social ostracism. The toll on Dirk's family continued over the next several years. First, the elder of Dirk's two brothers, Jon, committed suicide at the age of 27 years in a manner uncannily reminiscent of Mr. S.'s suicide. Some months later, Dirk's surviving brother, Rick, a poly-substance abuser, was incarcerated after being arrested and convicted of a drug-related felony. Finally, Dirk and his sister became estranged from each other, and by the time he began treatment, they were barely speaking to one another. Dirk, in fact, had little contact with anyone. After his parents' deaths, he spent a couple of years in the homes of various relatives, but eventually he decided to move back into his parents' house, where he lived alone. Dirk had been provided for quite generously in his father's will. He soon took over what remained of the family business, which included a strip mall and a small assortment of other business properties. At the time when he began weekly therapy, Dirk had monthly contact with some of his tenants when their rents became due and made occasional trips to the grocery store. He had not dated since high school and had only episodic contact with his paternal grandmother, whom he disliked. He slept in his parents' bedroom, which had not been redecorated after their deaths. There even was unrepaired damage from the shotgun blast that had killed his mother, although he did not at first appear discomfited by this fact and maintained that it was not abnormal or even especially noteworthy. He explained that he was loath to change or repair anything in the house, which he attributed to a tendency toward “procrastination.” People were unreliable, but his house, despite the carnage that had occurred there, remained a stabilizing force. Change was loathsome because it interfered with the integrity of important memories of the house and of the childhood lived within its walls.

Dirk was quite socially isolated and had a tremendous amount of discretionary time, two facts that were alternately frightening and reassuring to him. Although he wanted very much to become more involved with others and eventually to be in a serious relationship with a woman, he trusted no one. He believed others to be capable of great treachery, and from time to time, he revealed conspiratorial ideas that had a paranoid, if not psychotic, delusional resonance to them. He lived in a sparsely populated semirural area, and for the most part, he involved himself in solitary pursuits [Page 301] such as stamp collecting, reading, and fishing. He would hunt small game or shoot at targets with a collection of rifles, shotguns, and handguns that his father had left behind, and at times he spoke with obvious pleasure of methodically skinning and dressing the small animals he trapped or killed. There was little or no waste; even the skins could be used to make caps or mittens. He maintained that hunting and trapping animals was by no means unkind; indeed, it was far more humane than permitting the overpopulation and starvation of raccoons, muskrats, opossums, foxes, minks, and the like. Occasionally, he would add that he preferred the company of animals, even dead ones, to humans. They, unlike people, did not express jealousy and hatred.

As the treatment intensified, Dirk began to share a great deal more about his relationships with both parents. Sometimes, he would speak with profound sadness of his staggering loss. Needing both to make sense of the tragedy and to assign responsibility for it, he then would become enraged at his mother's lover. It was he who was to blame for everything that had happened, Dirk would declare. At other times, he described both of his parents as heinous or monstrous, having total disregard for the rest of the family's welfare.

Things never had been especially good between Dirk and his mother. She had a mild case of rubella during her pregnancy with Dirk, which he believed might have caused a physical anomaly as well as a congenital problem with his vision. Perhaps, he thought, she had rejected him in his infancy when the anomaly was discovered. The manner in which his mother described the anomaly, which later was removed, made him feel as though his physical appearance displeased, and perhaps even disgusted, her. Although he spent a great deal of time with her growing up, he recalled that she often was emotionally distant or upset with him.

From this time onward, he had gradually become less trusting of his mother and grew closer to his father, whom he emulated in a variety of ways. He often had noted that he and his father were very much alike. He had thought the world of this strong “macho” man who demanded strict obedience but also was capable of great kindness, particularly in acknowledgment of Dirk's frequent efforts to please him. It was quite painful for Dirk to think of this same strong father as a cuckold. It was even more frightening to think of him as weakened and castrated, and it was profoundly traumatic to believe that he could have been so uncaring about Dirk and his siblings as to actually carry out this unspeakably hateful crime of vengeance.

Early in his treatment, Dirk was able to express anger and disappointment with his mother for her lack of warmth and the painful way in which she avoided him, even shunned him. She had made him feel defective, small, and unimportant. This material was mined for what it revealed of the nature of Dirk's relational (selfobject) needs. We gradually learned how his mother's own limited capacity for empathy had interfered with the development of Dirk's capacity for pleasure in his own accomplishments, [Page 302] for healthy self-confidence and the indefatigable pursuit of important personal goals. In fact, Dirk avoided virtually any social situation where he thought others might disappoint him, where his mother's inability to mirror his boyhood efforts and accomplishments might be traumatically repeated. This was an important theme in our early explorations of Dirk's contact-shunning adaptation to the world outside his family home. However, this dynamic issue was not at the core of the transference-countertransference matrix that gradually evolved in my work with Dirk.

During the early spring, about 5 months into his treatment, Dirk gradually began to reveal more details of his relationship with his father. His father, he observed, was really more like an employer than a parent, forever assigning Dirk tasks, correcting his mistakes, and maintaining a certain aloofness and emotional distance from him. Although up until this point Dirk had tended to place more responsibility for the murder-suicide on the actions of his mother and her lover, he now began to view his father as having a greater role in the family tragedy. For the first time, he sounded genuinely angry. However, awareness of this proved to be exceedingly painful for him, and depressive thoughts and suicidal fantasies typically followed such discussions: “My father could have shot me…. In fact, sometimes I wish he had blown me away.”

During this same period, burglars broke into the strip mall that Dirk had inherited from his father's estate. This enraged Dirk, almost to the point of psychotic disorganization. He reacted to it as though his personal integrity had been violated, and he reported a series of dreams in which burglars were breaking into homes or he was being chased with people shooting at him. His associations were to his father, whom he described as a “castrating” parent with a need to keep his three sons subservient to him. Dirk observed, for perhaps the first time, that his father might have been rather narcissistic, lacking genuine empathy and interest in his three boys. He was beginning to think of himself and his two older brothers as really quite troubled, although in different ways. He then recounted the following dream:

[A man who looked like] Jack Benny was trying to break into my house to steal my valuables. He wanted me to think that he had rigged some electrical wire with a gas pipe to scare me and, thereby, force me to disclose the hiding place where my valuables were…. He was a mild-mannered man.

We hypothesized that Benny, a mild-mannered Jewish comedian whose initials were identical to my own, also might represent me or, in any event, aspects of Dirk's experience of the treatment process. In an important sense, I was asking Dirk to reveal the hidden location of treasured memories, feelings, and fantasies that he had worked unremittingly to conceal not only from others but also from himself. These interpretations seemed to make a good deal of sense to both of us, yet my recollection [Page 303] at the end of this hour was that I somehow was vaguely troubled. It also was approximately at this point in Dirk's treatment that I began to take copious notes. I rationalized that this was necessary because I felt unable to reconstruct the sessions afterward without them. However, I now believe that this note taking also was in the service of a different, fundamentally unconscious motive. From time to time, Dirk would complain that I was physically too close to him in the office or that I was watching him too intently during the hour, which made him feel self-conscious and ashamed. On several occasions, I actually had moved my chair farther away from him at his request. Again, in response to his anxiety, I had made a point of looking away from him precisely during those moments when I ordinarily would want to feel most connected to a client (e.g., when he had recalled a pioignant experience with his father or was talking about the aftermath of the tragedy). I also noted that it was following “good” hours—hours characterized by considerable affectivity and important revelations—that he would request that our meetings be held on a biweekly basis. When this occurred, probably a half dozen times over the 2 years he was in treatment with me, I recall feeling both disappointed and concerned. My efforts to convince him of the therapeutic value in exploring this phenomenon rather than altering the frequency of our meetings were not simply fruitless; they aroused tremendous anxiety, and several times Dirk threatened to stop coming altogether if I persisted. In effect, my compulsive note taking represented an unconscious compliance with Dirk's articulated request that I titrate the intensity of my involvement with him. At times, our interaction during sessions bore a marked similarity to his interactions with both parents, particularly his father. Like his father, I had become increasingly distant and aloof. On the other hand, Dirk exercised control over this relationship, which proved to be a critical distinction for him as the treatment evolved.

It was during a session in late July, some 9 months into treatment, that I reminded Dirk of my upcoming vacation. As we ended our hour, he remarked for the first time how similar we seemed to each other. I did not comment on this observation because we had reached the end of the hour. However, I believe that I felt rather uneasy about it. During the next session, our last hour prior to my vacation, Dirk reported that he was getting out more often and had been doing a modest degree of socializing. He was making a concerted effort to be less isolated. At the same time, he expressed a considerable degree of hostility when speaking of his (then-incarcerated) brother, whom he described as “exploitative” and deceitful. Toward the end of this hour, he asked where I would be going on vacation. On one previous occasion, Dirk had sought extra-therapeutic contact with me; that had been some months earlier when he called me at home, quite intoxicated, at 2 or 3 a.m. However, during his sessions, he rarely had asked me questions of a personal nature. I remember feeling compelled to answer this one, which I believed represented an important request. It was while I was on vacation some 800 miles away, in a somewhat isolated and unfamiliar setting, [Page 304] that I experienced a dramatic countertransference reaction inextricably linked to my work with Dirk. Although space does not permit a more detailed discussion here, at its core, this reaction faithfully reproduced two important elements of our work: Dirk's paranoia and the highly significant and traumatogenic elements of his relationship with both parents.

Although Dirk was not an easy client to treat, he was likeable. I felt this way from our first meeting, and I believe that this basic feeling for him permitted our work to continue despite his paranoia and a number of disturbing developments along the transference-countertransference axis. During the first weeks of therapy, I recall that although I found his story fully believable, I also felt shocked, overwhelmed, and at times even numbed by it. It was difficult, if not impossible, to conceive of the impact of such traumas occurring seriatim in one family.

Although I felt moved by Dirk's story and wished to convey this to him, his manner of narrating it was a powerful signal to me that he would not find this helpful, at least for the time being. It was as though he could not take in such feelings or allow me to be close in this way. I was not especially troubled by this, and I felt as though my principal task was simply to listen, make occasional inquiries, and provide a climate of acceptance. Although I believe that my discomfort with Dirk cumulated silently during those first few months of treatment, an important threshold was crossed with Dirk's revelation that he continued to sleep in his parents' bedroom. I found this not only bizarre but also frightening. When we attempted to discuss this, he was dismissive. I, on the other hand, was quite willing to let the matter rest, and it was only much later in his treatment that we were able to return to this dialogue. This fact, in combination with my awareness of Dirk's nearly obsessive love of hunting and trapping, led me to begin to view him not so much as a victim of trauma as a heartless and potentially dangerous individual. It did not occur to me until months later that each time he killed a muskrat or a raccoon, it might have served as a disguised reenactment of the original trauma and simultaneously permitted him to identify with an admired part of his father, who had taught him how to hunt and trap. Dirk, after all, had observed in an early session that he and his father were really quite similar. It may, of course, be argued that his paranoia and penchant for hunting, trapping, and skinning animals, in combination with my knowledge of the frightening traumas he had endured, might have helped to shape my countertransference-driven withdrawal and compulsive note taking. He also had requested, somewhat urgently, that I exercise caution lest he feel “trapped”; I was to pull my chair back, not make eye contact, and the like. But soon I felt trapped as well; I had altered my therapeutic modus operandi, and I became aware of experiencing mild apprehension on those days when Dirk came in for his appointments. Some of Dirk's sessions seemed interminable, and if I was feeling this way, then I think it likely that he was feeling something similar. Perhaps in this additional sense, both of us were feeling trapped.

As Dirk became increasingly aware of the depth of the injury that he believed his mother had caused him and of the rage he felt toward his father, the extent of his developmental arrest became more comprehensible. I had noted to myself at several junctures that Dirk spoke of his father, in particular, as though he still were alive. In an important sense, Dirk had been unable to bury either parent. Haunted by them, he was unable to relinquish his torturous ties to them. Eventually, the house came to symbolize not only the family tragedy that had begun there but also his relationship with both parents.

As Dirk developed greater awareness of the rage he felt for his father, a feeling that he had worked so hard to project, dissociate, and deny, he seemed to demonstrate greater interest in me and in our relationship. When he commented with some satisfaction that the two of us seemed to be similar, I suddenly recalled Dirk's earlier comment about how similar he and his father were. His associations to dream material as well seemed to equate me with his father. Like his father, I might attempt to trick him into a relationship where he was chronically exploited and mistreated and was reduced to a type of helpless indentured servitude. Although the oedipal significance of this dream was not inconsequential, with its reference to hidden valuables, I do not believe that this was the most salient dynamic issue insofar as our relationship was concerned. As mentioned earlier, I ended that hour feeling vaguely troubled in spite of Dirk's agreement that the interpretation was helpful. Although the dream was manifestly paranoid, an important truth about the asymmetry of the therapeutic relationship also was revealed. I was apprehensive because Dirk's associations had signaled the presence of a danger, and that danger now was perceived in some measure as coming from me.

Dirk's report that he was “getting out more” and was less reclusive should have been good news, although I recall reacting with but mild enthusiasm when he informed me of this shortly before my vacation. Dirk was just fine to work with so long as his paranoid fears prevented him from venturing out very far into the world of “real” relationships. However, the thought of Dirk no longer confined to a twilight existence, coupled with his increasing capacity both to feel and express rage, was an alarming one. What ultimately transformed my countertransference fantasies into a dramatic and disjunctive countertransference reaction was the haunting parallel—partially transference based, partially grounded in reality—that had emerged in Dirk's view of me as fundamentally similar to both him and his father. I now believe that my intensive countertransference reaction while on vacation had accomplished something that had simply not been possible despite careful introspection and reflection. I finally came close to experiencing Dirk's terror, although in my own idiosyncratic way. Like Dirk, I felt small, vulnerable, and alone. I was isolated and helpless, in unfamiliar surroundings, and cut off from contact with reality and the intersubjective world. Dirk was frightening, but it was even more frightening to be [Page 306] Dirk. As his therapist, I had been the hunter; suddenly, I was the hunted. I was convinced that I had betrayed Dirk in much the same way as his father had betrayed him, the trauma reenacted in his treatment. In effect, in this extra-therapeutic enactment, I felt not only as Dirk felt but also as I believe he might wish his father to feel—the dreaded and hated father against whom he sought redress for his grievances. Dirk, of course, had enacted both roles daily for well over 5 years; I had enacted them but for a single night.

The narrative case illustration used here highlights the complexity of the intersubjective milieu surrounding this young man's treatment and the relationship of past traumata to the evolving therapeutic relationship. The case study method permitted an examination of various historically important dynamic issues that might have relevance to the client's presenting symptomatology. It also revealed important parallels between features of the client's transference relationship and various unresolved issues between the client and his parents. Finally, reasons for the powerful countertransference reactions of the clinician were suggested and explored. This narrative case study is principally generative. It focuses on an exceptional case, addressing particular issues germane to the transference-countertransference matrix in adolescent treatment for which there is little antecedent clinical or theoretical literature. A range of researchable themes and issues (e.g., the impact of severe childhood trauma on personality development, handling of transference, recognition and use of disjunctive countertransference reactions) can be identified for subsequent investigation.

Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research

In-Depth Interviews

Sign in to access this content

Get a 30 day free trial, more like this, sage recommends.

We found other relevant content for you on other Sage platforms.

Have you created a personal profile? Login or create a profile so that you can save clips, playlists and searches

- Sign in/register

Navigating away from this page will delete your results

Please save your results to "My Self-Assessments" in your profile before navigating away from this page.

Sign in to my profile

Please sign into your institution before accessing your profile

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources have to offer.

You must have a valid academic email address to sign up.

Get off-campus access

- View or download all content my institution has access to.

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources has to offer.

- view my profile

- view my lists

- Previous Chapter

- Next Chapter

Narrative inquiry involves the sense-making of lived experiences through storytelling. The approach is gaining prominence across various social science disciplines. In this chapter, case study researchers are introduced to the concept of thinking narratively and employing narrative genres and methods to gain a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena in real-world contexts. The chapter discusses key conceptual, methodological and ethical considerations when combining narrative and case study approaches. It explores various ways in which researchers have incorporated narrative in case studies, such as narrative as the case, narrative of the case, narrative within the case, narrative around the case and the researcher’s own narrative behind the case. Additionally, the chapter addresses the importance of considering absent or marginalized narratives within case studies. The chapter concludes that narrative complements the focus of case study research on complexity and context by emphasizing inclusive representation and illuminating participant experiences and perspectives.

Benasso, S., Palumbo, M. and Pandolfini, V. (2019) ‘Narrating cases: A storytelling approach to case study analysis in the field of lifelong learning policies’, Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 11(2), pp.83–108.

Bold, C. (2012) Using Narrative in Research. London: Sage.

Brusentsev, A., Hitchens, M. and Richards, D. (2012, July) ‘An investigation of Vladimir Propp’s 31 functions and 8 broad character types and how they apply to the analysis of video games’, in Proceedings of the 8th Australasian Conference on Interactive Entertainment: Playing the System (pp.1–10).

Bunton, S.A. and Sandberg, S.F. (2016) ‘Case study research in health professions education’, Academic Medicine, 91(12):e3.

Clandinin, D.J. (2006) ‘Narrative inquiry: A methodology for studying lived experience’, Research Studies in Music Education, 27(1), pp.44–54.

Clandinin, D.J. and Connelly, F.M. (2000) Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Clandinin, D.J. and Huber, J. (2010) ‘Narrative inquiry’, in B. McGaw, E. Baker and P.P. Peterson, (eds.) International Encyclopaedia of Education (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Elsevier, pp.436–41.

Clandinin, D.J. and Rosiek, J. (2007) ‘Mapping a landscape of narrative inquiry: Borderland spaces and tensions’, in D.J. Clandinin, (ed.) Handbook of Narrative Inquiry: Mapping a Methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp.35–75.

Clandinin, J., Caine, V., Estefan, A., Huber, J., Murphy, M.S. and Steeves, P. (2015) ‘Places of practice: Learning to think narratively’, Narrative Works, 5(1), pp.22–39.