What is the Scientific Method: How does it work and why is it important?

The scientific method is a systematic process involving steps like defining questions, forming hypotheses, conducting experiments, and analyzing data. It minimizes biases and enables replicable research, leading to groundbreaking discoveries like Einstein's theory of relativity, penicillin, and the structure of DNA. This ongoing approach promotes reason, evidence, and the pursuit of truth in science.

Updated on October 28, 2024

Beginning in elementary school, we are exposed to the scientific method and taught how to put it into practice. As a tool for learning, it prepares children to think logically and use reasoning when seeking answers to questions.

Rather than jumping to conclusions, the scientific method gives us a recipe for exploring the world through observation and trial and error. We use it regularly, sometimes knowingly in academics or research, and sometimes subconsciously in our daily lives.

In this article we will refresh our memories on the particulars of the scientific method, discussing where it comes from, which elements comprise it, and how it is put into practice. Then, we will consider the importance of the scientific method, who uses it and under what circumstances.

What is the scientific method?

The scientific method is a dynamic process that involves objectively investigating questions through observation and experimentation . Applicable to all scientific disciplines, this systematic approach to answering questions is more accurately described as a flexible set of principles than as a fixed series of steps.

The following representations of the scientific method illustrate how it can be both condensed into broad categories and also expanded to reveal more and more details of the process. These graphics capture the adaptability that makes this concept universally valuable as it is relevant and accessible not only across age groups and educational levels but also within various contexts.

Steps in the scientific method

While the scientific method is versatile in form and function, it encompasses a collection of principles that create a logical progression to the process of problem solving:

- Define a question : Constructing a clear and precise problem statement that identifies the main question or goal of the investigation is the first step. The wording must lend itself to experimentation by posing a question that is both testable and measurable.

- Gather information and resources : Researching the topic in question to find out what is already known and what types of related questions others are asking is the next step in this process. This background information is vital to gaining a full understanding of the subject and in determining the best design for experiments.

- Form a hypothesis : Composing a concise statement that identifies specific variables and potential results, which can then be tested, is a crucial step that must be completed before any experimentation. An imperfection in the composition of a hypothesis can result in weaknesses to the entire design of an experiment.

- Perform the experiments : Testing the hypothesis by performing replicable experiments and collecting resultant data is another fundamental step of the scientific method. By controlling some elements of an experiment while purposely manipulating others, cause and effect relationships are established.

- Analyze the data : Interpreting the experimental process and results by recognizing trends in the data is a necessary step for comprehending its meaning and supporting the conclusions. Drawing inferences through this systematic process lends substantive evidence for either supporting or rejecting the hypothesis.

- Report the results : Sharing the outcomes of an experiment, through an essay, presentation, graphic, or journal article, is often regarded as a final step in this process. Detailing the project's design, methods, and results not only promotes transparency and replicability but also adds to the body of knowledge for future research.

- Retest the hypothesis : Repeating experiments to see if a hypothesis holds up in all cases is a step that is manifested through varying scenarios. Sometimes a researcher immediately checks their own work or replicates it at a future time, or another researcher will repeat the experiments to further test the hypothesis.

Where did the scientific method come from?

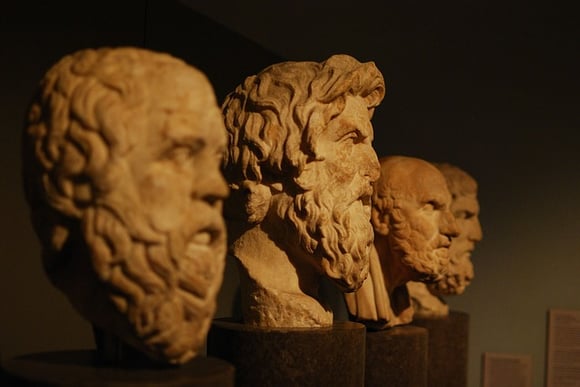

Oftentimes, ancient peoples attempted to answer questions about the unknown by:

- Making simple observations

- Discussing the possibilities with others deemed worthy of a debate

- Drawing conclusions based on dominant opinions and preexisting beliefs

For example, take Greek and Roman mythology. Myths were used to explain everything from the seasons and stars to the sun and death itself.

However, as societies began to grow through advancements in agriculture and language, ancient civilizations like Egypt and Babylonia shifted to a more rational analysis for understanding the natural world. They increasingly employed empirical methods of observation and experimentation that would one day evolve into the scientific method .

In the 4th century, Aristotle, considered the Father of Science by many, suggested these elements , which closely resemble the contemporary scientific method, as part of his approach for conducting science:

- Study what others have written about the subject.

- Look for the general consensus about the subject.

- Perform a systematic study of everything even partially related to the topic.

By continuing to emphasize systematic observation and controlled experiments, scholars such as Al-Kindi and Ibn al-Haytham helped expand this concept throughout the Islamic Golden Age .

In his 1620 treatise, Novum Organum , Sir Francis Bacon codified the scientific method, arguing not only that hypotheses must be tested through experiments but also that the results must be replicated to establish a truth. Coming at the height of the Scientific Revolution, this text made the scientific method accessible to European thinkers like Galileo and Isaac Newton who then put the method into practice.

As science modernized in the 19th century, the scientific method became more formalized, leading to significant breakthroughs in fields such as evolution and germ theory. Today, it continues to evolve, underpinning scientific progress in diverse areas like quantum mechanics, genetics, and artificial intelligence.

Why is the scientific method important?

The history of the scientific method illustrates how the concept developed out of a need to find objective answers to scientific questions by overcoming biases based on fear, religion, power, and cultural norms. This still holds true today.

By implementing this standardized approach to conducting experiments, the impacts of researchers’ personal opinions and preconceived notions are minimized. The organized manner of the scientific method prevents these and other mistakes while promoting the replicability and transparency necessary for solid scientific research.

The importance of the scientific method is best observed through its successes, for example:

- “ Albert Einstein stands out among modern physicists as the scientist who not only formulated a theory of revolutionary significance but also had the genius to reflect in a conscious and technical way on the scientific method he was using.” Devising a hypothesis based on the prevailing understanding of Newtonian physics eventually led Einstein to devise the theory of general relativity .

- Howard Florey “Perhaps the most useful lesson which has come out of the work on penicillin has been the demonstration that success in this field depends on the development and coordinated use of technical methods.” After discovering a mold that prevented the growth of Staphylococcus bacteria, Dr. Alexander Flemimg designed experiments to identify and reproduce it in the lab, thus leading to the development of penicillin .

- James D. Watson “Every time you understand something, religion becomes less likely. Only with the discovery of the double helix and the ensuing genetic revolution have we had grounds for thinking that the powers held traditionally to be the exclusive property of the gods might one day be ours. . . .” By using wire models to conceive a structure for DNA, Watson and Crick crafted a hypothesis for testing combinations of amino acids, X-ray diffraction images, and the current research in atomic physics, resulting in the discovery of DNA’s double helix structure .

Final thoughts

As the cases exemplify, the scientific method is never truly completed, but rather started and restarted. It gave these researchers a structured process that was easily replicated, modified, and built upon.

While the scientific method may “end” in one context, it never literally ends. When a hypothesis, design, methods, and experiments are revisited, the scientific method simply picks up where it left off. Each time a researcher builds upon previous knowledge, the scientific method is restored with the pieces of past efforts.

By guiding researchers towards objective results based on transparency and reproducibility, the scientific method acts as a defense against bias, superstition, and preconceived notions. As we embrace the scientific method's enduring principles, we ensure that our quest for knowledge remains firmly rooted in reason, evidence, and the pursuit of truth.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

Lucidly exploring and applying philosophy

- Fun Quizzes

- Logic Course

- Ethics Course

- Philosophy Course

Chapter 6: Scientific Problem Solving

If you prefer a video, click this button:

Scientific Problem Solving Video

Science is a method to discover empirical truths and patterns. Roughly speaking, the scientific method consists of

1) Observing

2) Forming a hypothesis

3) Testing the hypothesis and

4) Interpreting the data to confirm or disconfirm the hypothesis.

The beauty of science is that any scientific claim can be tested if you have the proper knowledge and equipment.

You can also use the scientific method to solve everyday problems: 1) Observe and clearly define the problem, 2) Form a hypothesis, 3) Test it, and 4) Confirm the hypothesis... or disconfirm it and start over.

So, the next time you are cursing in traffic or emotionally reacting to a problem, take a few deep breaths and then use this rational and scientific approach. Slow down, observe, hypothesize, and test.

Explain how you would solve these problems using the four steps of the scientific process.

Example: The fire alarm is not working.

1) Observe/Define the problem: it does not beep when I push the button.

2) Hypothesis: it is caused by a dead battery.

3) Test: try a new battery.

4) Confirm/Disconfirm: the alarm now works. If it does not work, start over by testing another hypothesis like “it has a loose wire.”

- My car will not start.

- My child is having problems reading.

- I owe $20,000, but only make $10 an hour.

- My boss is mean. I want him/her to stop using rude language towards me.

- My significant other is lazy. I want him/her to help out more.

6-8. Identify three problems where you can apply the scientific method.

*Answers will vary.

Application and Value

Science is more of a process than a body of knowledge. In our daily lives, we often emotionally react and jump to quick solutions when faced with problems, but following the four steps of the scientific process can help us slow down and discover more intelligent solutions.

In your study of philosophy, you will explore deeper questions about science. For example, are there any forms of knowledge that are nonscientific? Can science tell us what we ought to do? Can logical and mathematical truths be proven in a scientific way? Does introspection give knowledge even though I cannot scientifically observe your introspective thoughts? Is science truly objective? These are challenging questions that should help you discover the scope of science without diminishing its awesome power.

But the first step in answering these questions is knowing what science is, and this chapter clarifies its essence. Again, Science is not so much a body of knowledge as it is a method of observing, hypothesizing, and testing. This method is what all the sciences have in common.

Perhaps too science should involve falsifiability, which is a concept explored in the next chapter.

Return to Logic Home Next (Chapter 7, Falsifiability)

Click on my affiliate link above (Logic Book Image) to explore the most popular introduction to logic. If you purchase it, I recommend buying a less expensive older edition.

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

The 6 Scientific Method Steps and How to Use Them

General Education

When you’re faced with a scientific problem, solving it can seem like an impossible prospect. There are so many possible explanations for everything we see and experience—how can you possibly make sense of them all? Science has a simple answer: the scientific method.

The scientific method is a method of asking and answering questions about the world. These guiding principles give scientists a model to work through when trying to understand the world, but where did that model come from, and how does it work?

In this article, we’ll define the scientific method, discuss its long history, and cover each of the scientific method steps in detail.

What Is the Scientific Method?

At its most basic, the scientific method is a procedure for conducting scientific experiments. It’s a set model that scientists in a variety of fields can follow, going from initial observation to conclusion in a loose but concrete format.

The number of steps varies, but the process begins with an observation, progresses through an experiment, and concludes with analysis and sharing data. One of the most important pieces to the scientific method is skepticism —the goal is to find truth, not to confirm a particular thought. That requires reevaluation and repeated experimentation, as well as examining your thinking through rigorous study.

There are in fact multiple scientific methods, as the basic structure can be easily modified. The one we typically learn about in school is the basic method, based in logic and problem solving, typically used in “hard” science fields like biology, chemistry, and physics. It may vary in other fields, such as psychology, but the basic premise of making observations, testing, and continuing to improve a theory from the results remain the same.

The History of the Scientific Method

The scientific method as we know it today is based on thousands of years of scientific study. Its development goes all the way back to ancient Mesopotamia, Greece, and India.

The Ancient World

In ancient Greece, Aristotle devised an inductive-deductive process , which weighs broad generalizations from data against conclusions reached by narrowing down possibilities from a general statement. However, he favored deductive reasoning, as it identifies causes, which he saw as more important.

Aristotle wrote a great deal about logic and many of his ideas about reasoning echo those found in the modern scientific method, such as ignoring circular evidence and limiting the number of middle terms between the beginning of an experiment and the end. Though his model isn’t the one that we use today, the reliance on logic and thorough testing are still key parts of science today.

The Middle Ages

The next big step toward the development of the modern scientific method came in the Middle Ages, particularly in the Islamic world. Ibn al-Haytham, a physicist from what we now know as Iraq, developed a method of testing, observing, and deducing for his research on vision. al-Haytham was critical of Aristotle’s lack of inductive reasoning, which played an important role in his own research.

Other scientists, including Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī, Ibn Sina, and Robert Grosseteste also developed models of scientific reasoning to test their own theories. Though they frequently disagreed with one another and Aristotle, those disagreements and refinements of their methods led to the scientific method we have today.

Following those major developments, particularly Grosseteste’s work, Roger Bacon developed his own cycle of observation (seeing that something occurs), hypothesis (making a guess about why that thing occurs), experimentation (testing that the thing occurs), and verification (an outside person ensuring that the result of the experiment is consistent).

After joining the Franciscan Order, Bacon was granted a special commission to write about science; typically, Friars were not allowed to write books or pamphlets. With this commission, Bacon outlined important tenets of the scientific method, including causes of error, methods of knowledge, and the differences between speculative and experimental science. He also used his own principles to investigate the causes of a rainbow, demonstrating the method’s effectiveness.

Scientific Revolution

Throughout the Renaissance, more great thinkers became involved in devising a thorough, rigorous method of scientific study. Francis Bacon brought inductive reasoning further into the method, whereas Descartes argued that the laws of the universe meant that deductive reasoning was sufficient. Galileo’s research was also inductive reasoning-heavy, as he believed that researchers could not account for every possible variable; therefore, repetition was necessary to eliminate faulty hypotheses and experiments.

All of this led to the birth of the Scientific Revolution , which took place during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In 1660, a group of philosophers and physicians joined together to work on scientific advancement. After approval from England’s crown , the group became known as the Royal Society, which helped create a thriving scientific community and an early academic journal to help introduce rigorous study and peer review.

Previous generations of scientists had touched on the importance of induction and deduction, but Sir Isaac Newton proposed that both were equally important. This contribution helped establish the importance of multiple kinds of reasoning, leading to more rigorous study.

As science began to splinter into separate areas of study, it became necessary to define different methods for different fields. Karl Popper was a leader in this area—he established that science could be subject to error, sometimes intentionally. This was particularly tricky for “soft” sciences like psychology and social sciences, which require different methods. Popper’s theories furthered the divide between sciences like psychology and “hard” sciences like chemistry or physics.

Paul Feyerabend argued that Popper’s methods were too restrictive for certain fields, and followed a less restrictive method hinged on “anything goes,” as great scientists had made discoveries without the Scientific Method. Feyerabend suggested that throughout history scientists had adapted their methods as necessary, and that sometimes it would be necessary to break the rules. This approach suited social and behavioral scientists particularly well, leading to a more diverse range of models for scientists in multiple fields to use.

The Scientific Method Steps

Though different fields may have variations on the model, the basic scientific method is as follows:

#1: Make Observations

Notice something, such as the air temperature during the winter, what happens when ice cream melts, or how your plants behave when you forget to water them.

#2: Ask a Question

Turn your observation into a question. Why is the temperature lower during the winter? Why does my ice cream melt? Why does my toast always fall butter-side down?

This step can also include doing some research. You may be able to find answers to these questions already, but you can still test them!

#3: Make a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an educated guess of the answer to your question. Why does your toast always fall butter-side down? Maybe it’s because the butter makes that side of the bread heavier.

A good hypothesis leads to a prediction that you can test, phrased as an if/then statement. In this case, we can pick something like, “If toast is buttered, then it will hit the ground butter-first.”

#4: Experiment

Your experiment is designed to test whether your predication about what will happen is true. A good experiment will test one variable at a time —for example, we’re trying to test whether butter weighs down one side of toast, making it more likely to hit the ground first.

The unbuttered toast is our control variable. If we determine the chance that a slice of unbuttered toast, marked with a dot, will hit the ground on a particular side, we can compare those results to our buttered toast to see if there’s a correlation between the presence of butter and which way the toast falls.

If we decided not to toast the bread, that would be introducing a new question—whether or not toasting the bread has any impact on how it falls. Since that’s not part of our test, we’ll stick with determining whether the presence of butter has any impact on which side hits the ground first.

#5: Analyze Data

After our experiment, we discover that both buttered toast and unbuttered toast have a 50/50 chance of hitting the ground on the buttered or marked side when dropped from a consistent height, straight down. It looks like our hypothesis was incorrect—it’s not the butter that makes the toast hit the ground in a particular way, so it must be something else.

Since we didn’t get the desired result, it’s back to the drawing board. Our hypothesis wasn’t correct, so we’ll need to start fresh. Now that you think about it, your toast seems to hit the ground butter-first when it slides off your plate, not when you drop it from a consistent height. That can be the basis for your new experiment.

#6: Communicate Your Results

Good science needs verification. Your experiment should be replicable by other people, so you can put together a report about how you ran your experiment to see if other peoples’ findings are consistent with yours.

This may be useful for class or a science fair. Professional scientists may publish their findings in scientific journals, where other scientists can read and attempt their own versions of the same experiments. Being part of a scientific community helps your experiments be stronger because other people can see if there are flaws in your approach—such as if you tested with different kinds of bread, or sometimes used peanut butter instead of butter—that can lead you closer to a good answer.

A Scientific Method Example: Falling Toast

We’ve run through a quick recap of the scientific method steps, but let’s look a little deeper by trying again to figure out why toast so often falls butter side down.

#1: Make Observations

At the end of our last experiment, where we learned that butter doesn’t actually make toast more likely to hit the ground on that side, we remembered that the times when our toast hits the ground butter side first are usually when it’s falling off a plate.

The easiest question we can ask is, “Why is that?”

We can actually search this online and find a pretty detailed answer as to why this is true. But we’re budding scientists—we want to see it in action and verify it for ourselves! After all, good science should be replicable, and we have all the tools we need to test out what’s really going on.

Why do we think that buttered toast hits the ground butter-first? We know it’s not because it’s heavier, so we can strike that out. Maybe it’s because of the shape of our plate?

That’s something we can test. We’ll phrase our hypothesis as, “If my toast slides off my plate, then it will fall butter-side down.”

Just seeing that toast falls off a plate butter-side down isn’t enough for us. We want to know why, so we’re going to take things a step further—we’ll set up a slow-motion camera to capture what happens as the toast slides off the plate.

We’ll run the test ten times, each time tilting the same plate until the toast slides off. We’ll make note of each time the butter side lands first and see what’s happening on the video so we can see what’s going on.

When we review the footage, we’ll likely notice that the bread starts to flip when it slides off the edge, changing how it falls in a way that didn’t happen when we dropped it ourselves.

That answers our question, but it’s not the complete picture —how do other plates affect how often toast hits the ground butter-first? What if the toast is already butter-side down when it falls? These are things we can test in further experiments with new hypotheses!

Now that we have results, we can share them with others who can verify our results. As mentioned above, being part of the scientific community can lead to better results. If your results were wildly different from the established thinking about buttered toast, that might be cause for reevaluation. If they’re the same, they might lead others to make new discoveries about buttered toast. At the very least, you have a cool experiment you can share with your friends!

Key Scientific Method Tips

Though science can be complex, the benefit of the scientific method is that it gives you an easy-to-follow means of thinking about why and how things happen. To use it effectively, keep these things in mind!

Don’t Worry About Proving Your Hypothesis

One of the important things to remember about the scientific method is that it’s not necessarily meant to prove your hypothesis right. It’s great if you do manage to guess the reason for something right the first time, but the ultimate goal of an experiment is to find the true reason for your observation to occur, not to prove your hypothesis right.

Good science sometimes means that you’re wrong. That’s not a bad thing—a well-designed experiment with an unanticipated result can be just as revealing, if not more, than an experiment that confirms your hypothesis.

Be Prepared to Try Again

If the data from your experiment doesn’t match your hypothesis, that’s not a bad thing. You’ve eliminated one possible explanation, which brings you one step closer to discovering the truth.

The scientific method isn’t something you’re meant to do exactly once to prove a point. It’s meant to be repeated and adapted to bring you closer to a solution. Even if you can demonstrate truth in your hypothesis, a good scientist will run an experiment again to be sure that the results are replicable. You can even tweak a successful hypothesis to test another factor, such as if we redid our buttered toast experiment to find out whether different kinds of plates affect whether or not the toast falls butter-first. The more we test our hypothesis, the stronger it becomes!

What’s Next?

Want to learn more about the scientific method? These important high school science classes will no doubt cover it in a variety of different contexts.

Test your ability to follow the scientific method using these at-home science experiments for kids !

Need some proof that science is fun? Try making slime

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Melissa Brinks graduated from the University of Washington in 2014 with a Bachelor's in English with a creative writing emphasis. She has spent several years tutoring K-12 students in many subjects, including in SAT prep, to help them prepare for their college education.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

How it works

For Organizations

Join Mindtools

Related Articles

What Is Problem Solving?

The Straw Man Concept

The Problem-Definition Process

Heuristic Methods

The Four Frame Approach

Article • 5 min read

Using the Scientific Method to Solve Problems

How the scientific method and reasoning can help simplify processes and solve problems.

Written by the Mindtools Content Team

Let's join Mindtools to have an ad free experience!

The processes of problem-solving and decision-making can be complicated and drawn out. In this article we look at how the scientific method, along with deductive and inductive reasoning can help simplify these processes.

‘It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has information. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit our theories, instead of theories to suit facts.’ Sherlock Holmes

The Scientific Method

The scientific method is a process used to explore observations and answer questions. Originally used by scientists looking to prove new theories, its use has spread into many other areas, including that of problem-solving and decision-making.

The scientific method is designed to eliminate the influences of bias, prejudice and personal beliefs when testing a hypothesis or theory. It has developed alongside science itself, with origins going back to the 13th century. The scientific method is generally described as a series of steps.

- observations/theory

- explanation/conclusion

The first step is to develop a theory about the particular area of interest. A theory, in the context of logic or problem-solving, is a conjecture or speculation about something that is not necessarily fact, often based on a series of observations.

Once a theory has been devised, it can be questioned and refined into more specific hypotheses that can be tested. The hypotheses are potential explanations for the theory.

The testing, and subsequent analysis, of these hypotheses will eventually lead to a conclus ion which can prove or disprove the original theory.

Applying the Scientific Method to Problem-Solving

How can the scientific method be used to solve a problem, such as the color printer is not working?

1. Use observations to develop a theory.

In order to solve the problem, it must first be clear what the problem is. Observations made about the problem should be used to develop a theory. In this particular problem the theory might be that the color printer has run out of ink. This theory is developed as the result of observing the increasingly faded output from the printer.

2. Form a hypothesis.

Note down all the possible reasons for the problem. In this situation they might include:

- The printer is set up as the default printer for all 40 people in the department and so is used more frequently than necessary.

- There has been increased usage of the printer due to non-work related printing.

- In an attempt to reduce costs, poor quality ink cartridges with limited amounts of ink in them have been purchased.

- The printer is faulty.

All these possible reasons are hypotheses.

3. Test the hypothesis.

Once as many hypotheses (or reasons) as possible have been thought of, then each one can be tested to discern if it is the cause of the problem. An appropriate test needs to be devised for each hypothesis. For example, it is fairly quick to ask everyone to check the default settings of the printer on each PC, or to check if the cartridge supplier has changed.

4. Analyze the test results.

Once all the hypotheses have been tested, the results can be analyzed. The type and depth of analysis will be dependant on each individual problem, and the tests appropriate to it. In many cases the analysis will be a very quick thought process. In others, where considerable information has been collated, a more structured approach, such as the use of graphs, tables or spreadsheets, may be required.

5. Draw a conclusion.

Based on the results of the tests, a conclusion can then be drawn about exactly what is causing the problem. The appropriate remedial action can then be taken, such as asking everyone to amend their default print settings, or changing the cartridge supplier.

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

The scientific method involves the use of two basic types of reasoning, inductive and deductive.

Inductive reasoning makes a conclusion based on a set of empirical results. Empirical results are the product of the collection of evidence from observations. For example:

‘Every time it rains the pavement gets wet, therefore rain must be water’.

There has been no scientific determination in the hypothesis that rain is water, it is purely based on observation. The formation of a hypothesis in this manner is sometimes referred to as an educated guess. An educated guess, whilst not based on hard facts, must still be plausible, and consistent with what we already know, in order to present a reasonable argument.

Deductive reasoning can be thought of most simply in terms of ‘If A and B, then C’. For example:

- if the window is above the desk, and

- the desk is above the floor, then

- the window must be above the floor

It works by building on a series of conclusions, which results in one final answer.

Social Sciences and the Scientific Method

The scientific method can be used to address any situation or problem where a theory can be developed. Although more often associated with natural sciences, it can also be used to develop theories in social sciences (such as psychology, sociology and linguistics), using both quantitative and qualitative methods.

Quantitative information is information that can be measured, and tends to focus on numbers and frequencies. Typically quantitative information might be gathered by experiments, questionnaires or psychometric tests. Qualitative information, on the other hand, is based on information describing meaning, such as human behavior, and the reasons behind it. Qualitative information is gathered by way of interviews and case studies, which are possibly not as statistically accurate as quantitative methods, but provide a more in-depth and rich description.

The resultant information can then be used to prove, or disprove, a hypothesis. Using a mix of quantitative and qualitative information is more likely to produce a rounded result based on the factual, quantitative information enriched and backed up by actual experience and qualitative information.

In terms of problem-solving or decision-making, for example, the qualitative information is that gained by looking at the ‘how’ and ‘why’ , whereas quantitative information would come from the ‘where’, ‘what’ and ‘when’.

It may seem easy to come up with a brilliant idea, or to suspect what the cause of a problem may be. However things can get more complicated when the idea needs to be evaluated, or when there may be more than one potential cause of a problem. In these situations, the use of the scientific method, and its associated reasoning, can help the user come to a decision, or reach a solution, secure in the knowledge that all options have been considered.

This premium resource is exclusive to Mindtools Members.

To continue, you will need to either login or join Mindtools.

Our members enjoy unparalleled access to thousands of training resources, covering a wide range of topics, all designed to help you develop your management and leadership skills

Already a member? Login now

Special holiday offer! 30% off subscriptions to Mindtools

With Mindtools, you’ll un wrap practical tools, expert insights and self-paced learning to thrive as a manager and leader.

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mindtools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Key Management Skills

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Building a Culture of Belonging

EDI Challenges for Managers

For Individuals

Mindtools Store

Discover something new today

Mindtools member newsletter december 19, 2024.

Let's Get It Done!

Impact Analysis

Identifying the Full Consequences of Change

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting your people skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Organize your ideas, with affinity diagrams infographic.

Infographic Transcript

Infographic

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Women in Leadership

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Member Newsletter

Introducing the Management Skills Framework

Transparent Communication

Social Sensitivity

Self-Awareness and Self-Regulation

Team Goal Setting

Recognition

Inclusivity

Active Listening

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Oct 27, 2024 · While the scientific method is versatile in form and function, it encompasses a collection of principles that create a logical progression to the process of problem solving: Define a question: Constructing a clear and precise problem statement that identifies the main question or goal of the investigation is the first step. The wording must ...

Scientific Problem Solving Video. Science is a method to discover empirical truths and patterns. Roughly speaking, the scientific method consists of. 1) Observing. 2) Forming a hypothesis . 3) Testing the hypothesis and . 4) Interpreting the data to confirm or disconfirm the hypothesis.

The scientific method was not invented by any one person, but is the outcome of centuries of debate about how best to find out how the natural world works. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle was among the first known people to promote that observation and reasoning must be applied to figure out how nature works.

The one we typically learn about in school is the basic method, based in logic and problem solving, typically used in “hard” science fields like biology, chemistry, and physics. It may vary in other fields, such as psychology, but the basic premise of making observations, testing, and continuing to improve a theory from the results remain ...

The Scientific Method. The scientific method is a process used to explore observations and answer questions. Originally used by scientists looking to prove new theories, its use has spread into many other areas, including that of problem-solving and decision-making.

Mar 14, 2024 · The scientific method is a step-by-step problem-solving process. These steps include: ... It's a step-by-step problem-solving process that involves: (1) observation, (2) asking questions, (3 ...