Experimental Method In Psychology

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

The experimental method involves the manipulation of variables to establish cause-and-effect relationships. The key features are controlled methods and the random allocation of participants into controlled and experimental groups .

What is an Experiment?

An experiment is an investigation in which a hypothesis is scientifically tested. An independent variable (the cause) is manipulated in an experiment, and the dependent variable (the effect) is measured; any extraneous variables are controlled.

An advantage is that experiments should be objective. The researcher’s views and opinions should not affect a study’s results. This is good as it makes the data more valid and less biased.

There are three types of experiments you need to know:

1. Lab Experiment

A laboratory experiment in psychology is a research method in which the experimenter manipulates one or more independent variables and measures the effects on the dependent variable under controlled conditions.

A laboratory experiment is conducted under highly controlled conditions (not necessarily a laboratory) where accurate measurements are possible.

The researcher uses a standardized procedure to determine where the experiment will take place, at what time, with which participants, and in what circumstances.

Participants are randomly allocated to each independent variable group.

Examples are Milgram’s experiment on obedience and Loftus and Palmer’s car crash study .

- Strength : It is easier to replicate (i.e., copy) a laboratory experiment. This is because a standardized procedure is used.

- Strength : They allow for precise control of extraneous and independent variables. This allows a cause-and-effect relationship to be established.

- Limitation : The artificiality of the setting may produce unnatural behavior that does not reflect real life, i.e., low ecological validity. This means it would not be possible to generalize the findings to a real-life setting.

- Limitation : Demand characteristics or experimenter effects may bias the results and become confounding variables .

2. Field Experiment

A field experiment is a research method in psychology that takes place in a natural, real-world setting. It is similar to a laboratory experiment in that the experimenter manipulates one or more independent variables and measures the effects on the dependent variable.

However, in a field experiment, the participants are unaware they are being studied, and the experimenter has less control over the extraneous variables .

Field experiments are often used to study social phenomena, such as altruism, obedience, and persuasion. They are also used to test the effectiveness of interventions in real-world settings, such as educational programs and public health campaigns.

An example is Holfing’s hospital study on obedience .

- Strength : behavior in a field experiment is more likely to reflect real life because of its natural setting, i.e., higher ecological validity than a lab experiment.

- Strength : Demand characteristics are less likely to affect the results, as participants may not know they are being studied. This occurs when the study is covert.

- Limitation : There is less control over extraneous variables that might bias the results. This makes it difficult for another researcher to replicate the study in exactly the same way.

3. Natural Experiment

A natural experiment in psychology is a research method in which the experimenter observes the effects of a naturally occurring event or situation on the dependent variable without manipulating any variables.

Natural experiments are conducted in the day (i.e., real life) environment of the participants, but here, the experimenter has no control over the independent variable as it occurs naturally in real life.

Natural experiments are often used to study psychological phenomena that would be difficult or unethical to study in a laboratory setting, such as the effects of natural disasters, policy changes, or social movements.

For example, Hodges and Tizard’s attachment research (1989) compared the long-term development of children who have been adopted, fostered, or returned to their mothers with a control group of children who had spent all their lives in their biological families.

Here is a fictional example of a natural experiment in psychology:

Researchers might compare academic achievement rates among students born before and after a major policy change that increased funding for education.

In this case, the independent variable is the timing of the policy change, and the dependent variable is academic achievement. The researchers would not be able to manipulate the independent variable, but they could observe its effects on the dependent variable.

- Strength : behavior in a natural experiment is more likely to reflect real life because of its natural setting, i.e., very high ecological validity.

- Strength : Demand characteristics are less likely to affect the results, as participants may not know they are being studied.

- Strength : It can be used in situations in which it would be ethically unacceptable to manipulate the independent variable, e.g., researching stress .

- Limitation : They may be more expensive and time-consuming than lab experiments.

- Limitation : There is no control over extraneous variables that might bias the results. This makes it difficult for another researcher to replicate the study in exactly the same way.

Key Terminology

Ecological validity.

The degree to which an investigation represents real-life experiences.

Experimenter effects

These are the ways that the experimenter can accidentally influence the participant through their appearance or behavior.

Demand characteristics

The clues in an experiment lead the participants to think they know what the researcher is looking for (e.g., the experimenter’s body language).

Independent variable (IV)

The variable the experimenter manipulates (i.e., changes) is assumed to have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

Dependent variable (DV)

Variable the experimenter measures. This is the outcome (i.e., the result) of a study.

Extraneous variables (EV)

All variables which are not independent variables but could affect the results (DV) of the experiment. EVs should be controlled where possible.

Confounding variables

Variable(s) that have affected the results (DV), apart from the IV. A confounding variable could be an extraneous variable that has not been controlled.

Random Allocation

Randomly allocating participants to independent variable conditions means that all participants should have an equal chance of participating in each condition.

The principle of random allocation is to avoid bias in how the experiment is carried out and limit the effects of participant variables.

Order effects

Changes in participants’ performance due to their repeating the same or similar test more than once. Examples of order effects include:

(i) practice effect: an improvement in performance on a task due to repetition, for example, because of familiarity with the task;

(ii) fatigue effect: a decrease in performance of a task due to repetition, for example, because of boredom or tiredness.

Experimental Psychology: 10 Examples & Definition

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Experimental psychology refers to studying psychological phenomena using scientific methods. Originally, the primary scientific method involved manipulating one variable and observing systematic changes in another variable.

Today, psychologists utilize several types of scientific methodologies.

Experimental psychology examines a wide range of psychological phenomena, including: memory, sensation and perception, cognitive processes, motivation, emotion, developmental processes, in addition to the neurophysiological concomitants of each of these subjects.

Studies are conducted on both animal and human participants, and must comply with stringent requirements and controls regarding the ethical treatment of both.

Definition of Experimental Psychology

Experimental psychology is a branch of psychology that utilizes scientific methods to investigate the mind and behavior.

It involves the systematic and controlled study of human and animal behavior through observation and experimentation .

Experimental psychologists design and conduct experiments to understand cognitive processes, perception, learning, memory, emotion, and many other aspects of psychology. They often manipulate variables ( independent variables ) to see how this affects behavior or mental processes (dependent variables).

The findings from experimental psychology research are often used to better understand human behavior and can be applied in a range of contexts, such as education, health, business, and more.

Experimental Psychology Examples

1. The Puzzle Box Studies (Thorndike, 1898) Placing different cats in a box that can only be escaped by pulling a cord, and then taking detailed notes on how long it took for them to escape allowed Edward Thorndike to derive the Law of Effect: actions followed by positive consequences are more likely to occur again, and actions followed by negative consequences are less likely to occur again (Thorndike, 1898).

2. Reinforcement Schedules (Skinner, 1956) By placing rats in a Skinner Box and changing when and how often the rats are rewarded for pressing a lever, it is possible to identify how each schedule results in different behavior patterns (Skinner, 1956). This led to a wide range of theoretical ideas around how rewards and consequences can shape the behaviors of both animals and humans.

3. Observational Learning (Bandura, 1980) Some children watch a video of an adult punching and kicking a Bobo doll. Other children watch a video in which the adult plays nicely with the doll. By carefully observing the children’s behavior later when in a room with a Bobo doll, researchers can determine if television violence affects children’s behavior (Bandura, 1980).

4. The Fallibility of Memory (Loftus & Palmer, 1974) A group of participants watch the same video of two cars having an accident. Two weeks later, some are asked to estimate the rate of speed the cars were going when they “smashed” into each other. Some participants are asked to estimate the rate of speed the cars were going when they “bumped” into each other. Changing the phrasing of the question changes the memory of the eyewitness.

5. Intrinsic Motivation in the Classroom (Dweck, 1990) To investigate the role of autonomy on intrinsic motivation, half of the students are told they are “free to choose” which tasks to complete. The other half of the students are told they “must choose” some of the tasks. Researchers then carefully observe how long the students engage in the tasks and later ask them some questions about if they enjoyed doing the tasks or not.

6. Systematic Desensitization (Wolpe, 1958) A clinical psychologist carefully documents his treatment of a patient’s social phobia with progressive relaxation. At first, the patient is trained to monitor, tense, and relax various muscle groups while viewing photos of parties. Weeks later, they approach a stranger to ask for directions, initiate a conversation on a crowded bus, and attend a small social gathering. The therapist’s notes are transcribed into a scientific report and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

7. Study of Remembering (Bartlett, 1932) Bartlett’s work is a seminal study in the field of memory, where he used the concept of “schema” to describe an organized pattern of thought or behavior. He conducted a series of experiments using folk tales to show that memory recall is influenced by cultural schemas and personal experiences.

8. Study of Obedience (Milgram, 1963) This famous study explored the conflict between obedience to authority and personal conscience. Milgram found that a majority of participants were willing to administer what they believed were harmful electric shocks to a stranger when instructed by an authority figure, highlighting the power of authority and situational factors in driving behavior.

9. Pavlov’s Dog Study (Pavlov, 1927) Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, conducted a series of experiments that became a cornerstone in the field of experimental psychology. Pavlov noticed that dogs would salivate when they saw food. He then began to ring a bell each time he presented the food to the dogs. After a while, the dogs began to salivate merely at the sound of the bell. This experiment demonstrated the principle of “classical conditioning.”

10, Piaget’s Stages of Development (Piaget, 1958) Jean Piaget proposed a theory of cognitive development in children that consists of four distinct stages: the sensorimotor stage (birth to 2 years), where children learn about the world through their senses and motor activities, through to the the formal operational stage (12 years and beyond), where abstract reasoning and hypothetical thinking develop. Piaget’s theory is an example of experimental psychology as it was developed through systematic observation and experimentation on children’s problem-solving behaviors .

Types of Research Methodologies in Experimental Psychology

Researchers utilize several different types of research methodologies since the early days of Wundt (1832-1920).

1. The Experiment

The experiment involves the researcher manipulating the level of one variable, called the Independent Variable (IV), and then observing changes in another variable, called the Dependent Variable (DV).

The researcher is interested in determining if the IV causes changes in the DV. For example, does television violence make children more aggressive?

So, some children in the study, called research participants, will watch a show with TV violence, called the treatment group. Others will watch a show with no TV violence, called the control group.

So, there are two levels of the IV: violence and no violence. Next, children will be observed to see if they act more aggressively. This is the DV.

If TV violence makes children more aggressive, then the children that watched the violent show will me more aggressive than the children that watched the non-violent show.

A key requirement of the experiment is random assignment . Each research participant is assigned to one of the two groups in a way that makes it a completely random process. This means that each group will have a mix of children: different personality types, diverse family backgrounds, and range of intelligence levels.

2. The Longitudinal Study

A longitudinal study involves selecting a sample of participants and then following them for years, or decades, periodically collecting data on the variables of interest.

For example, a researcher might be interested in determining if parenting style affects academic performance of children. Parenting style is called the predictor variable , and academic performance is called the outcome variable .

Researchers will begin by randomly selecting a group of children to be in the study. Then, they will identify the type of parenting practices used when the children are 4 and 5 years old.

A few years later, perhaps when the children are 8 and 9, the researchers will collect data on their grades. This process can be repeated over the next 10 years, including through college.

If parenting style has an effect on academic performance, then the researchers will see a connection between the predictor variable and outcome variable.

Children raised with parenting style X will have higher grades than children raised with parenting style Y.

3. The Case Study

The case study is an in-depth study of one individual. This is a research methodology often used early in the examination of a psychological phenomenon or therapeutic treatment.

For example, in the early days of treating phobias, a clinical psychologist may try teaching one of their patients how to relax every time they see the object that creates so much fear and anxiety, such as a large spider.

The therapist would take very detailed notes on how the teaching process was implemented and the reactions of the patient. When the treatment had been completed, those notes would be written in a scientific form and submitted for publication in a scientific journal for other therapists to learn from.

There are several other types of methodologies available which vary different aspects of the three described above. The researcher will select a methodology that is most appropriate to the phenomenon they want to examine.

They also must take into account various practical considerations such as how much time and resources are needed to complete the study. Conducting research always costs money.

People and equipment are needed to carry-out every study, so researchers often try to obtain funding from their university or a government agency.

Origins and Key Developments in Experimental Psychology

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (1832-1920) is considered one of the fathers of modern psychology. He was a physiologist and philosopher and helped establish psychology as a distinct discipline (Khaleefa, 1999).

In 1879 he established the world’s first psychology research lab at the University of Leipzig. This is considered a key milestone for establishing psychology as a scientific discipline. In addition to being the first person to use the term “psychologist,” to describe himself, he also founded the discipline’s first scientific journal Philosphische Studien in 1883.

Another notable figure in the development of experimental psychology is Ernest Weber . Trained as a physician, Weber studied sensation and perception and created the first quantitative law in psychology.

The equation denotes how judgments of sensory differences are relative to previous levels of sensation, referred to as the just-noticeable difference (jnd). This is known today as Weber’s Law (Hergenhahn, 2009).

Gustav Fechner , one of Weber’s students, published the first book on experimental psychology in 1860, titled Elemente der Psychophysik. His worked centered on the measurement of psychophysical facets of sensation and perception, with many of his methods still in use today.

The first American textbook on experimental psychology was Elements of Physiological Psychology, published in 1887 by George Trumball Ladd .

Ladd also established a psychology lab at Yale University, while Stanley Hall and Charles Sanders continued Wundt’s work at a lab at Johns Hopkins University.

In the late 1800s, Charles Pierce’s contribution to experimental psychology is especially noteworthy because he invented the concept of random assignment (Stigler, 1992; Dehue, 1997).

Go Deeper: 15 Random Assignment Examples

This procedure ensures that each participant has an equal chance of being placed in any of the experimental groups (e.g., treatment or control group). This eliminates the influence of confounding factors related to inherent characteristics of the participants.

Random assignment is a fundamental criterion for a study to be considered a valid experiment.

From there, experimental psychology flourished in the 20th century as a science and transformed into an approach utilized in cognitive psychology, developmental psychology, and social psychology .

Today, the term experimental psychology refers to the study of a wide range of phenomena and involves methodologies not limited to the manipulation of variables.

The Scientific Process and Experimental Psychology

The one thing that makes psychology a science and distinguishes it from its roots in philosophy is the reliance upon the scientific process to answer questions. This makes psychology a science was the main goal of its earliest founders such as Wilhelm Wundt.

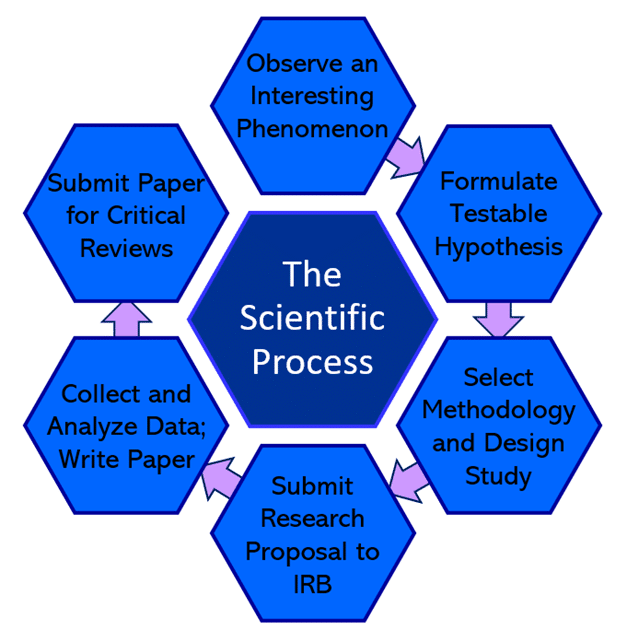

There are numerous steps in the scientific process, outlined in the graphic below.

1. Observation

First, the scientist observes an interesting phenomenon that sparks a question. For example, are the memories of eyewitnesses really reliable, or are they subject to bias or unintentional manipulation?

2. Hypothesize

Next, this question is converted into a testable hypothesis. For instance: the words used to question a witness can influence what they think they remember.

3. Devise a Study

Then the researcher(s) select a methodology that will allow them to test that hypothesis. In this case, the researchers choose the experiment, which will involve randomly assigning some participants to different conditions.

In one condition, participants are asked a question that implies a certain memory (treatment group), while other participants are asked a question which is phrased neutrally and does not imply a certain memory (control group).

The researchers then write a proposal that describes in detail the procedures they want to use, how participants will be selected, and the safeguards they will employ to ensure the rights of the participants.

That proposal is submitted to an Institutional Review Board (IRB). The IRB is comprised of a panel of researchers, community representatives, and other professionals that are responsible for reviewing all studies involving human participants.

4. Conduct the Study

If the IRB accepts the proposal, then the researchers may begin collecting data. After the data has been collected, it is analyzed using a software program such as SPSS.

Those analyses will either support or reject the hypothesis. That is, either the participants’ memories were affected by the wording of the question, or not.

5. Publish the study

Finally, the researchers write a paper detailing their procedures and results of the statistical analyses. That paper is then submitted to a scientific journal.

The lead editor of that journal will then send copies of the paper to 3-5 experts in that subject. Each of those experts will read the paper and basically try to find as many things wrong with it as possible. Because they are experts, they are very good at this task.

After reading those critiques, most likely, the editor will send the paper back to the researchers and require that they respond to the criticisms, collect more data, or reject the paper outright.

In some cases, the study was so well-done that the criticisms were minimal and the editor accepts the paper. It then gets published in the scientific journal several months later.

That entire process can easily take 2 years, usually more. But, the findings of that study went through a very rigorous process. This means that we can have substantial confidence that the conclusions of the study are valid.

Experimental psychology refers to utilizing a scientific process to investigate psychological phenomenon.

There are a variety of methods employed today. They are used to study a wide range of subjects, including memory, cognitive processes, emotions and the neurophysiological basis of each.

The history of psychology as a science began in the 1800s primarily in Germany. As interest grew, the field expanded to the United States where several influential research labs were established.

As more methodologies were developed, the field of psychology as a science evolved into a prolific scientific discipline that has provided invaluable insights into human behavior.

Bartlett, F. C., & Bartlett, F. C. (1995). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology . Cambridge university press.

Dehue, T. (1997). Deception, efficiency, and random groups: Psychology and the gradual origination of the random group design. Isis , 88 (4), 653-673.

Ebbinghaus, H. (2013). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Annals of neurosciences , 20 (4), 155.

Hergenhahn, B. R. (2009). An introduction to the history of psychology. Belmont. CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning .

Khaleefa, O. (1999). Who is the founder of psychophysics and experimental psychology? American Journal of Islam and Society , 16 (2), 1-26.

Loftus, E. F., & Palmer, J. C. (1974). Reconstruction of auto-mobile destruction : An example of the interaction between language and memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal behavior , 13, 585-589.

Pavlov, I.P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes . Dover, New York.

Piaget, J. (1959). The language and thought of the child (Vol. 5). Psychology Press.

Piaget, J., Fraisse, P., & Reuchlin, M. (2014). Experimental psychology its scope and method: Volume I (Psychology Revivals): History and method . Psychology Press.

Skinner, B. F. (1956). A case history in scientlfic method. American Psychologist, 11 , 221-233

Stigler, S. M. (1992). A historical view of statistical concepts in psychology and educational research. American Journal of Education , 101 (1), 60-70.

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. Psychological Review Monograph Supplement 2 .

Wolpe, J. (1958). Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Appendix: Images reproduced as Text

Definition: Experimental psychology is a branch of psychology that focuses on conducting systematic and controlled experiments to study human behavior and cognition.

Overview: Experimental psychology aims to gather empirical evidence and explore cause-and-effect relationships between variables. Experimental psychologists utilize various research methods, including laboratory experiments, surveys, and observations, to investigate topics such as perception, memory, learning, motivation, and social behavior .

Example: The Pavlov’s Dog experimental psychology experiment used scientific methods to develop a theory about how learning and association occur in animals. The same concepts were subsequently used in the study of humans, wherein psychology-based ideas about learning were developed. Pavlov’s use of the empirical evidence was foundational to the study’s success.

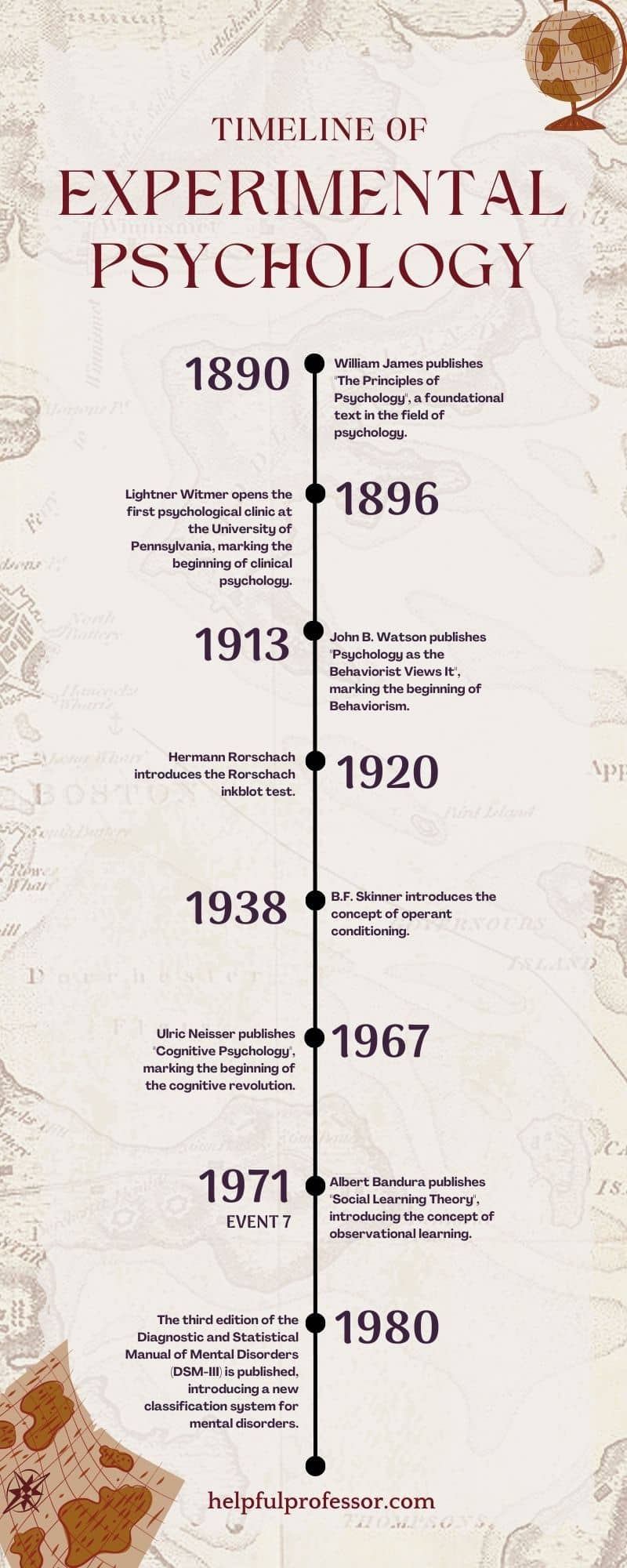

Experimental Psychology Milestones:

1890: William James publishes “The Principles of Psychology”, a foundational text in the field of psychology.

1896: Lightner Witmer opens the first psychological clinic at the University of Pennsylvania, marking the beginning of clinical psychology.

1913: John B. Watson publishes “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It”, marking the beginning of Behaviorism.

1920: Hermann Rorschach introduces the Rorschach inkblot test.

1938: B.F. Skinner introduces the concept of operant conditioning .

1967: Ulric Neisser publishes “Cognitive Psychology” , marking the beginning of the cognitive revolution.

1980: The third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) is published, introducing a new classification system for mental disorders.

The Scientific Process

- Observe an interesting phenomenon

- Formulate testable hypothesis

- Select methodology and design study

- Submit research proposal to IRB

- Collect and analyzed data; write paper

- Submit paper for critical reviews

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

B.A. in Psychology

What Is Experimental Psychology?

The science of psychology spans several fields. There are dozens of disciplines in psychology, including abnormal psychology, cognitive psychology and social psychology.

One way to view these fields is to separate them into two types: applied vs. experimental psychology. These groups describe virtually any type of work in psychology.

The following sections explore what experimental psychology is and some examples of what it covers.

Experimental psychology seeks to explore and better understand behavior through empirical research methods. This work allows findings to be employed in real-world applications (applied psychology) across fields such as clinical psychology, educational psychology, forensic psychology, sports psychology, and social psychology. Experimental psychology is able to shed light on people’s personalities and life experiences by examining what the way people behave and how behavior is shaped throughout life, along with other theoretical questions. The field looks at a wide range of behavioral topics including sensation, perception, attention, memory, cognition, and emotion, according to the American Psychological Association (APA).

Research is the focus of experimental psychology. Using scientific methods to collect data and perform research, experimental psychology focuses on certain questions, and, one study at a time, reveals information that contributes to larger findings or a conclusion. Due to the breadth and depth of certain areas of study, researchers can spend their entire careers looking at a complex research question.

Experimental Psychology in Action

The APA writes about one experimental psychologist, Robert McCann, who is now retired after 19 years working at NASA. During his time at NASA, his work focused on the user experience — on land and in space — where he applied his expertise to cockpit system displays, navigation systems, and safety displays used by astronauts in NASA spacecraft. McCann’s knowledge of human information processing allowed him to help NASA design shuttle displays that can increase the safety of shuttle missions. He looked at human limitations of attention and display processing to gauge what people can reliably see and correctly interpret on an instrument panel. McCann played a key role in helping determining the features of cockpit displays without overloading the pilot or taxing their attention span.

“One of the purposes of the display was to alert the astronauts to the presence of a failure that interrupted power in a specific region,” McCann said, “The most obvious way to depict this interruption was to simply remove (or dim) the white line(s) connecting the affected components. Basic research on visual attention has shown that humans do not notice the removal of a display feature very easily when the display is highly cluttered. We are much better at noticing a feature or object that is suddenly added to a display.” McCann utilized his knowledge in experimental psychology to research and develop this very important development for NASA.

Valve Corporation

Another experimental psychologist, Mike Ambinder, uses his expertise to help design video games. He is a senior experimental psychologist at Valve Corporation, a video game developer and developer of the software distribution platform Steam. Ambinder told Orlando Weekly that his career working on gaming hits such as Portal 2 and Left 4 Dead “epitomizes the intersection between scientific innovation and electronic entertainment.” His career started when he gave a presentation to Valve on applying psychology to game design; this occurred while he was finishing his PhD in experimental design. “I’m very lucky to have landed at a company where freedom and autonomy and analytical decision-making are prized,” he said. “I realized how fortunate I was to work for a company that would encourage someone with a background in psychology to see what they could contribute in a field where they had no prior experience.”

Ambinder spends his time on data analysis, hardware research, play-testing methodologies, and on any aspect of games where knowledge of human behavior could be useful. Ambinder described Valve’s process for refining a product as straightforward. “We come up with a game design (our hypothesis), and we place it in front of people external to the company (our play-test or experiment). We gather their feedback, and then iterate and improve the design (refining the theory). It’s essentially the scientific method applied to game design, and the end result is the consequence of many hours of applying this process.” To gather play-test data, Ambinder is engaged in the newer field of biofeedback technology, which can quantify gamers’ enjoyment. His research looks at unobtrusive measurements of facial expressions that can achieve such goals. Ambinder is also examining eye-tracking as a next-generation input method.

Pursue Your Career Goals in Psychology

Develop a greater understanding of psychology concepts and applications with Concordia St. Paul’s online bachelor’s in psychology . Enjoy small class sizes with a personal learning environment geared toward your success, and learn from knowledgeable faculty who have industry experience.

- Abnormal Psychology

- Assessment (IB)

- Biological Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminology

- Developmental Psychology

- Extended Essay

- General Interest

- Health Psychology

- Human Relationships

- IB Psychology

- IB Psychology HL Extensions

- Internal Assessment (IB)

- Love and Marriage

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Prejudice and Discrimination

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Research Methodology

- Revision and Exam Preparation

- Social and Cultural Psychology

- Studies and Theories

- Teaching Ideas

What is an “experiment?”

Travis Dixon October 7, 2017 Research Methodology

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

If you’re reading this it’s probably because your teacher has assigned this as homework because you’ve called a study an “experiment” when it wasn’t an experiment at all. So this post is to help you know exactly when to use the term “experiment”, and when it’s safe just to say “study.”

But before we get to that, let’s first clarify why this is important knowledge. I think there are two reasons:

- If you use the term experiment incorrectly in an exam it will suggest to the examiner that you have limited knowledge – this will affect your marks.

- Research methods (and especially experiments) are the backbone of psychological research and so they’re a pretty important concept to understand.

Definition of experiment:

An experiment in psychology is when there is a study conducted that investigates the direct effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable.

Tip: If you’re not sure if it’s an experiment, you’re always safe to call it a “study.”

Before you can call a study an experiment, you have to identify the independent variable. Ask yourself:

- “Are there different groups in the study that the researchers are comparing?”

For example, in this study about serotonin’s effects on the brain we can see that there are two groups: drinking the placebo or the drink that reduces serotonin. So the IV is serotonin levels.

Experiments test causal relationships.

If there are different groups and there is clearly an IV, you then need to ask yourself, “are the researchers studying the effects on a DV?” In other words, is there a causal relationship between the IV and DV being examined?

If you look at the examples in the studies in this post , you’ll see that all of these studies are clearly investigating the effects of an IV on a DV:

- Serotonin study: the effects of serotonin levels (IV) on prefrontal cortex activity (DV)

- Rat experiment: the effects of testosterone (IV) on aggression (DV)

- Watching TV (Bandura): the effects of observing violence (IV) on aggression (DV).

So if the study is testing a causal relationship between an IV and a DV, you my friend, have got yourself an experiment 🙂

Laboratories are good places to conduct experiments because the conditions can be controlled so the IV can be isolated – this is essential when testing causal relationships.

So when is a study not an experiment?

A simple test would be to ask yourself:

- Did the researchers create the groups/conditions?

If they did, then you’ve got an experiment.

- Serotonin study: the researchers chose who drank which drink and when.

- Rat study: the researchers chose which rats to castrate and which ones not to.

- TV study: they told which kids to watch TV and which ones not to.

If the researchers didn’t create the groups you might be better to call it a “study” to be on the safe side.

In a true experiment it is the researchers who manipulate the independent variable (i.e. they create the groups/conditions in the experiment).

For example, in studies that compare cultures the researchers cannot create the groups because people are born into their existing cultures. These types of studies are most commonly correlational studies.

Another example is research on communication in relationships: the researchers compare the differences between couples with positive communication with those who have negative communication, but they didn’t create these groups – they occurred naturally. These are also correlational studies.

To conclude: if the researchers create the groups for comparison it’s an experiment. If not, you’re safer to call it a “study.”

Qualitative studies are never experiments, so be extra-careful when using this word in Paper 3.

But just to get tricky, there are some experiments where the independent variable is naturally occurring. These are called natural experiments (or quasi-experiments). So if you have a study with a naturally occurring variable, before you can call it an experiment you have to ask yourself:

- Are they testing a causal relationship between the IV and the DV?

But the problem is in order to answer this question you need to know quite a bit about the methodology. This is because you have to know if they’ve controlled for confounding variables in either their design or their statistical analyses. If they’ve tried to control confounding variables and isolate the IV as the only variable affecting the DV, you can call it an experiment.

But here we’re getting pretty complicated, which is why it might better to err on the side of caution with naturally occurring IVs and call them studies if you’re not sure if they’re experimental or not (another way to check is to ask your teacher).

What makes an experiment “quasi?” (Read More)

I hope this post helps. If you need anything clarified or you have questions about a specific study, please feel free to post it in the comments.

Travis Dixon is an IB Psychology teacher, author, workshop leader, examiner and IA moderator.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Does Experimental Psychology Study Behavior?

Purpose, methods, and history

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Sean is a fact-checker and researcher with experience in sociology, field research, and data analytics.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sean-Blackburn-1000-a8b2229366944421bc4b2f2ba26a1003.jpg)

- Why It Matters

What factors influence people's behaviors and thoughts? Experimental psychology utilizes scientific methods to answer these questions by researching the mind and behavior. Experimental psychologists conduct experiments to learn more about why people do certain things.

Overview of Experimental Psychology

Why do people do the things they do? What factors influence how personality develops? And how do our behaviors and experiences shape our character?

These are just a few of the questions that psychologists explore, and experimental methods allow researchers to create and empirically test hypotheses. By studying such questions, researchers can also develop theories that enable them to describe, explain, predict, and even change human behaviors.

For example, researchers might utilize experimental methods to investigate why people engage in unhealthy behaviors. By learning more about the underlying reasons why these behaviors occur, researchers can then search for effective ways to help people avoid such actions or replace unhealthy choices with more beneficial ones.

Why Experimental Psychology Matters

While students are often required to take experimental psychology courses during undergraduate and graduate school , think about this subject as a methodology rather than a singular area within psychology. People in many subfields of psychology use these techniques to conduct research on everything from childhood development to social issues.

Experimental psychology is important because the findings play a vital role in our understanding of the human mind and behavior.

By better understanding exactly what makes people tick, psychologists and other mental health professionals can explore new approaches to treating psychological distress and mental illness. These are often topics of experimental psychology research.

Experimental Psychology Methods

So how exactly do researchers investigate the human mind and behavior? Because the mind is so complex, it seems like a challenging task to explore the many factors that contribute to how we think, act, and feel.

Experimental psychologists use a variety of different research methods and tools to investigate human behavior. Methods in the experimental psychology category include experiments, case studies, correlational research, and naturalistic observations.

Experiments

Experimentation remains the primary standard in psychological research. In some cases, psychologists can perform experiments to determine if there is a cause-and-effect relationship between different variables.

The basics of conducting a psychology experiment involve:

- Randomly assigning participants to groups

- Operationally defining variables

- Developing a hypothesis

- Manipulating independent variables

- Measuring dependent variables

One experimental psychology research example would be to perform a study to look at whether sleep deprivation impairs performance on a driving test. The experimenter could control other variables that might influence the outcome, varying the amount of sleep participants get the night before.

All of the participants would then take the same driving test via a simulator or on a controlled course. By analyzing the results, researchers can determine if changes in the independent variable (amount of sleep) led to differences in the dependent variable (performance on a driving test).

Case Studies

Case studies allow researchers to study an individual or group of people in great depth. When performing a case study, the researcher collects every single piece of data possible, often observing the person or group over a period of time and in a variety of situations. They also collect detailed information about their subject's background—including family history, education, work, and social life—is also collected.

Such studies are often performed in instances where experimentation is not possible. For example, a scientist might conduct a case study when the person of interest has had a unique or rare experience that could not be replicated in a lab.

Correlational Research

Correlational studies are an experimental psychology method that makes it possible for researchers to look at relationships between different variables. For example, a psychologist might note that as one variable increases, another tends to decrease.

While such studies can look at relationships, they cannot be used to imply causal relationships. The golden rule is that correlation does not equal causation.

Naturalistic Observations

Naturalistic observation gives researchers the opportunity to watch people in their natural environments. This experimental psychology method can be particularly useful in cases where the investigators believe that a lab setting might have an undue influence on participant behaviors.

What Experimental Psychologists Do

Experimental psychologists work in a wide variety of settings, including colleges, universities, research centers, government, and private businesses. Some of these professionals teach experimental methods to students while others conduct research on cognitive processes, animal behavior, neuroscience, personality, and other subject areas.

Those who work in academic settings often teach psychology courses in addition to performing research and publishing their findings in professional journals. Other experimental psychologists work with businesses to discover ways to make employees more productive or to create a safer workplace—a specialty area known as human factors psychology .

Experimental Psychology Research Examples

Some topics that might be explored in experimental psychology research include how music affects motivation, the impact social media has on mental health , and whether a certain color changes one's thoughts or perceptions.

History of Experimental Psychology

To understand how experimental psychology got where it is today, it can be helpful to look at how it originated. Psychology is a relatively young discipline, emerging in the late 1800s. While it started as part of philosophy and biology, it officially became its own field of study when early psychologist Wilhelm Wundt founded the first laboratory devoted to the study of experimental psychology.

Some of the important events that helped shape the field of experimental psychology include:

- 1874 - Wilhelm Wundt published the first experimental psychology textbook, "Grundzüge der physiologischen Psychologie" ("Principles of Physiological Psychology").

- 1875 - William James opened a psychology lab in the United States. The lab was created for the purpose of class demonstrations rather than to perform original experimental research.

- 1879 - The first experimental psychology lab was founded in Leipzig, Germany. Modern experimental psychology dates back to the establishment of the very first psychology lab by pioneering psychologist Wilhelm Wundt during the late nineteenth century.

- 1883 - G. Stanley Hall opened the first experimental psychology lab in the United States at John Hopkins University.

- 1885 - Herman Ebbinghaus published his famous "Über das Gedächtnis" ("On Memory"), which was later translated to English as "Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology." In the work, Ebbinghaus described learning and memory experiments that he conducted on himself.

- 1887 - George Truball Ladd published his textbook "Elements of Physiological Psychology," the first American book to include a significant amount of information on experimental psychology.

- 1887 - James McKeen Cattell established the world's third experimental psychology lab at the University of Pennsylvania.

- 1890 - William James published his classic textbook, "The Principles of Psychology."

- 1891 - Mary Whiton Calkins established an experimental psychology lab at Wellesley College, becoming the first woman to form a psychology lab.

- 1893 - G. Stanley Hall founded the American Psychological Association , the largest professional and scientific organization of psychologists in the United States.

- 1920 - John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner conducted their now-famous Little Albert Experiment , in which they demonstrated that emotional reactions could be classically conditioned in people.

- 1929 - Edwin Boring's book "A History of Experimental Psychology" was published. Boring was an influential experimental psychologist who was devoted to the use of experimental methods in psychology research.

- 1955 - Lee Cronbach published "Construct Validity in Psychological Tests," which popularized the use of construct validity in psychological studies.

- 1958 - Harry Harlow published "The Nature of Love," which described his experiments with rhesus monkeys on attachment and love.

- 1961 - Albert Bandura conducted his famous Bobo doll experiment, which demonstrated the effects of observation on aggressive behavior.

Experimental Psychology Uses

While experimental psychology is sometimes thought of as a separate branch or subfield of psychology, experimental methods are widely used throughout all areas of psychology.

- Developmental psychologists use experimental methods to study how people grow through childhood and over the course of a lifetime.

- Social psychologists use experimental techniques to study how people are influenced by groups.

- Health psychologists rely on experimentation and research to better understand the factors that contribute to wellness and disease.

A Word From Verywell

The experimental method in psychology helps us learn more about how people think and why they behave the way they do. Experimental psychologists can research a variety of topics using many different experimental methods. Each one contributes to what we know about the mind and human behavior.

Shaughnessy JJ, Zechmeister EB, Zechmeister JS. Research Methods in Psychology . McGraw-Hill.

Heale R, Twycross A. What is a case study? . Evid Based Nurs. 2018;21(1):7-8. doi:10.1136/eb-2017-102845

Chiang IA, Jhangiani RS, Price PC. Correlational research . In: Research Methods in Psychology, 2nd Canadian edition. BCcampus Open Education.

Pierce T. Naturalistic observation . Radford University.

Kantowitz BH, Roediger HL, Elmes DG. Experimental Psychology . Cengage Learning.

Weiner IB, Healy AF, Proctor RW. Handbook of Psychology: Volume 4, Experimental Psychology . John Wiley & Sons.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Experimental Research

23 Experiment Basics

Learning objectives.

- Explain what an experiment is and recognize examples of studies that are experiments and studies that are not experiments.

- Distinguish between the manipulation of the independent variable and control of extraneous variables and explain the importance of each.

- Recognize examples of confounding variables and explain how they affect the internal validity of a study.

- Define what a control condition is, explain its purpose in research on treatment effectiveness, and describe some alternative types of control conditions.

What Is an Experiment?

As we saw earlier in the book, an experiment is a type of study designed specifically to answer the question of whether there is a causal relationship between two variables. In other words, whether changes in one variable (referred to as an independent variable ) cause a change in another variable (referred to as a dependent variable ). Experiments have two fundamental features. The first is that the researchers manipulate, or systematically vary, the level of the independent variable. The different levels of the independent variable are called conditions . For example, in Darley and Latané’s experiment, the independent variable was the number of witnesses that participants believed to be present. The researchers manipulated this independent variable by telling participants that there were either one, two, or five other students involved in the discussion, thereby creating three conditions. For a new researcher, it is easy to confuse these terms by believing there are three independent variables in this situation: one, two, or five students involved in the discussion, but there is actually only one independent variable (number of witnesses) with three different levels or conditions (one, two or five students). The second fundamental feature of an experiment is that the researcher exerts control over, or minimizes the variability in, variables other than the independent and dependent variable. These other variables are called extraneous variables . Darley and Latané tested all their participants in the same room, exposed them to the same emergency situation, and so on. They also randomly assigned their participants to conditions so that the three groups would be similar to each other to begin with. Notice that although the words manipulation and control have similar meanings in everyday language, researchers make a clear distinction between them. They manipulate the independent variable by systematically changing its levels and control other variables by holding them constant.

Manipulation of the Independent Variable

Again, to manipulate an independent variable means to change its level systematically so that different groups of participants are exposed to different levels of that variable, or the same group of participants is exposed to different levels at different times. For example, to see whether expressive writing affects people’s health, a researcher might instruct some participants to write about traumatic experiences and others to write about neutral experiences. The different levels of the independent variable are referred to as conditions , and researchers often give the conditions short descriptive names to make it easy to talk and write about them. In this case, the conditions might be called the “traumatic condition” and the “neutral condition.”

Notice that the manipulation of an independent variable must involve the active intervention of the researcher. Comparing groups of people who differ on the independent variable before the study begins is not the same as manipulating that variable. For example, a researcher who compares the health of people who already keep a journal with the health of people who do not keep a journal has not manipulated this variable and therefore has not conducted an experiment. This distinction is important because groups that already differ in one way at the beginning of a study are likely to differ in other ways too. For example, people who choose to keep journals might also be more conscientious, more introverted, or less stressed than people who do not. Therefore, any observed difference between the two groups in terms of their health might have been caused by whether or not they keep a journal, or it might have been caused by any of the other differences between people who do and do not keep journals. Thus the active manipulation of the independent variable is crucial for eliminating potential alternative explanations for the results.

Of course, there are many situations in which the independent variable cannot be manipulated for practical or ethical reasons and therefore an experiment is not possible. For example, whether or not people have a significant early illness experience cannot be manipulated, making it impossible to conduct an experiment on the effect of early illness experiences on the development of hypochondriasis. This caveat does not mean it is impossible to study the relationship between early illness experiences and hypochondriasis—only that it must be done using nonexperimental approaches. We will discuss this type of methodology in detail later in the book.

Independent variables can be manipulated to create two conditions and experiments involving a single independent variable with two conditions are often referred to as a single factor two-level design . However, sometimes greater insights can be gained by adding more conditions to an experiment. When an experiment has one independent variable that is manipulated to produce more than two conditions it is referred to as a single factor multi level design . So rather than comparing a condition in which there was one witness to a condition in which there were five witnesses (which would represent a single-factor two-level design), Darley and Latané’s experiment used a single factor multi-level design, by manipulating the independent variable to produce three conditions (a one witness, a two witnesses, and a five witnesses condition).

Control of Extraneous Variables

As we have seen previously in the chapter, an extraneous variable is anything that varies in the context of a study other than the independent and dependent variables. In an experiment on the effect of expressive writing on health, for example, extraneous variables would include participant variables (individual differences) such as their writing ability, their diet, and their gender. They would also include situational or task variables such as the time of day when participants write, whether they write by hand or on a computer, and the weather. Extraneous variables pose a problem because many of them are likely to have some effect on the dependent variable. For example, participants’ health will be affected by many things other than whether or not they engage in expressive writing. This influencing factor can make it difficult to separate the effect of the independent variable from the effects of the extraneous variables, which is why it is important to control extraneous variables by holding them constant.

Extraneous Variables as “Noise”

Extraneous variables make it difficult to detect the effect of the independent variable in two ways. One is by adding variability or “noise” to the data. Imagine a simple experiment on the effect of mood (happy vs. sad) on the number of happy childhood events people are able to recall. Participants are put into a negative or positive mood (by showing them a happy or sad video clip) and then asked to recall as many happy childhood events as they can. The two leftmost columns of Table 5.1 show what the data might look like if there were no extraneous variables and the number of happy childhood events participants recalled was affected only by their moods. Every participant in the happy mood condition recalled exactly four happy childhood events, and every participant in the sad mood condition recalled exactly three. The effect of mood here is quite obvious. In reality, however, the data would probably look more like those in the two rightmost columns of Table 5.1 . Even in the happy mood condition, some participants would recall fewer happy memories because they have fewer to draw on, use less effective recall strategies, or are less motivated. And even in the sad mood condition, some participants would recall more happy childhood memories because they have more happy memories to draw on, they use more effective recall strategies, or they are more motivated. Although the mean difference between the two groups is the same as in the idealized data, this difference is much less obvious in the context of the greater variability in the data. Thus one reason researchers try to control extraneous variables is so their data look more like the idealized data in Table 5.1 , which makes the effect of the independent variable easier to detect (although real data never look quite that good).

One way to control extraneous variables is to hold them constant. This technique can mean holding situation or task variables constant by testing all participants in the same location, giving them identical instructions, treating them in the same way, and so on. It can also mean holding participant variables constant. For example, many studies of language limit participants to right-handed people, who generally have their language areas isolated in their left cerebral hemispheres [1] . Left-handed people are more likely to have their language areas isolated in their right cerebral hemispheres or distributed across both hemispheres, which can change the way they process language and thereby add noise to the data.

In principle, researchers can control extraneous variables by limiting participants to one very specific category of person, such as 20-year-old, heterosexual, female, right-handed psychology majors. The obvious downside to this approach is that it would lower the external validity of the study—in particular, the extent to which the results can be generalized beyond the people actually studied. For example, it might be unclear whether results obtained with a sample of younger lesbian women would apply to older gay men. In many situations, the advantages of a diverse sample (increased external validity) outweigh the reduction in noise achieved by a homogeneous one.

Extraneous Variables as Confounding Variables

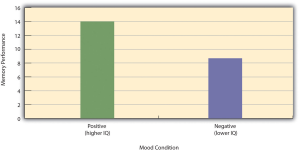

The second way that extraneous variables can make it difficult to detect the effect of the independent variable is by becoming confounding variables. A confounding variable is an extraneous variable that differs on average across levels of the independent variable (i.e., it is an extraneous variable that varies systematically with the independent variable). For example, in almost all experiments, participants’ intelligence quotients (IQs) will be an extraneous variable. But as long as there are participants with lower and higher IQs in each condition so that the average IQ is roughly equal across the conditions, then this variation is probably acceptable (and may even be desirable). What would be bad, however, would be for participants in one condition to have substantially lower IQs on average and participants in another condition to have substantially higher IQs on average. In this case, IQ would be a confounding variable.

To confound means to confuse , and this effect is exactly why confounding variables are undesirable. Because they differ systematically across conditions—just like the independent variable—they provide an alternative explanation for any observed difference in the dependent variable. Figure 5.1 shows the results of a hypothetical study, in which participants in a positive mood condition scored higher on a memory task than participants in a negative mood condition. But if IQ is a confounding variable—with participants in the positive mood condition having higher IQs on average than participants in the negative mood condition—then it is unclear whether it was the positive moods or the higher IQs that caused participants in the first condition to score higher. One way to avoid confounding variables is by holding extraneous variables constant. For example, one could prevent IQ from becoming a confounding variable by limiting participants only to those with IQs of exactly 100. But this approach is not always desirable for reasons we have already discussed. A second and much more general approach—random assignment to conditions—will be discussed in detail shortly.

Treatment and Control Conditions

In psychological research, a treatment is any intervention meant to change people’s behavior for the better. This intervention includes psychotherapies and medical treatments for psychological disorders but also interventions designed to improve learning, promote conservation, reduce prejudice, and so on. To determine whether a treatment works, participants are randomly assigned to either a treatment condition , in which they receive the treatment, or a control condition , in which they do not receive the treatment. If participants in the treatment condition end up better off than participants in the control condition—for example, they are less depressed, learn faster, conserve more, express less prejudice—then the researcher can conclude that the treatment works. In research on the effectiveness of psychotherapies and medical treatments, this type of experiment is often called a randomized clinical trial .

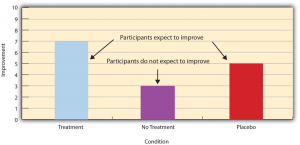

There are different types of control conditions. In a no-treatment control condition , participants receive no treatment whatsoever. One problem with this approach, however, is the existence of placebo effects. A placebo is a simulated treatment that lacks any active ingredient or element that should make it effective, and a placebo effect is a positive effect of such a treatment. Many folk remedies that seem to work—such as eating chicken soup for a cold or placing soap under the bed sheets to stop nighttime leg cramps—are probably nothing more than placebos. Although placebo effects are not well understood, they are probably driven primarily by people’s expectations that they will improve. Having the expectation to improve can result in reduced stress, anxiety, and depression, which can alter perceptions and even improve immune system functioning (Price, Finniss, & Benedetti, 2008) [2] .

Placebo effects are interesting in their own right (see Note “The Powerful Placebo” ), but they also pose a serious problem for researchers who want to determine whether a treatment works. Figure 5.2 shows some hypothetical results in which participants in a treatment condition improved more on average than participants in a no-treatment control condition. If these conditions (the two leftmost bars in Figure 5.2 ) were the only conditions in this experiment, however, one could not conclude that the treatment worked. It could be instead that participants in the treatment group improved more because they expected to improve, while those in the no-treatment control condition did not.

Fortunately, there are several solutions to this problem. One is to include a placebo control condition , in which participants receive a placebo that looks much like the treatment but lacks the active ingredient or element thought to be responsible for the treatment’s effectiveness. When participants in a treatment condition take a pill, for example, then those in a placebo control condition would take an identical-looking pill that lacks the active ingredient in the treatment (a “sugar pill”). In research on psychotherapy effectiveness, the placebo might involve going to a psychotherapist and talking in an unstructured way about one’s problems. The idea is that if participants in both the treatment and the placebo control groups expect to improve, then any improvement in the treatment group over and above that in the placebo control group must have been caused by the treatment and not by participants’ expectations. This difference is what is shown by a comparison of the two outer bars in Figure 5.4 .

Of course, the principle of informed consent requires that participants be told that they will be assigned to either a treatment or a placebo control condition—even though they cannot be told which until the experiment ends. In many cases the participants who had been in the control condition are then offered an opportunity to have the real treatment. An alternative approach is to use a wait-list control condition , in which participants are told that they will receive the treatment but must wait until the participants in the treatment condition have already received it. This disclosure allows researchers to compare participants who have received the treatment with participants who are not currently receiving it but who still expect to improve (eventually). A final solution to the problem of placebo effects is to leave out the control condition completely and compare any new treatment with the best available alternative treatment. For example, a new treatment for simple phobia could be compared with standard exposure therapy. Because participants in both conditions receive a treatment, their expectations about improvement should be similar. This approach also makes sense because once there is an effective treatment, the interesting question about a new treatment is not simply “Does it work?” but “Does it work better than what is already available?

The Powerful Placebo

Many people are not surprised that placebos can have a positive effect on disorders that seem fundamentally psychological, including depression, anxiety, and insomnia. However, placebos can also have a positive effect on disorders that most people think of as fundamentally physiological. These include asthma, ulcers, and warts (Shapiro & Shapiro, 1999) [3] . There is even evidence that placebo surgery—also called “sham surgery”—can be as effective as actual surgery.

Medical researcher J. Bruce Moseley and his colleagues conducted a study on the effectiveness of two arthroscopic surgery procedures for osteoarthritis of the knee (Moseley et al., 2002) [4] . The control participants in this study were prepped for surgery, received a tranquilizer, and even received three small incisions in their knees. But they did not receive the actual arthroscopic surgical procedure. Note that the IRB would have carefully considered the use of deception in this case and judged that the benefits of using it outweighed the risks and that there was no other way to answer the research question (about the effectiveness of a placebo procedure) without it. The surprising result was that all participants improved in terms of both knee pain and function, and the sham surgery group improved just as much as the treatment groups. According to the researchers, “This study provides strong evidence that arthroscopic lavage with or without débridement [the surgical procedures used] is not better than and appears to be equivalent to a placebo procedure in improving knee pain and self-reported function” (p. 85).

- Knecht, S., Dräger, B., Deppe, M., Bobe, L., Lohmann, H., Flöel, A., . . . Henningsen, H. (2000). Handedness and hemispheric language dominance in healthy humans. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 123 (12), 2512-2518. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/123.12.2512 ↵

- Price, D. D., Finniss, D. G., & Benedetti, F. (2008). A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: Recent advances and current thought. Annual Review of Psychology, 59 , 565–590. ↵

- Shapiro, A. K., & Shapiro, E. (1999). The powerful placebo: From ancient priest to modern physician . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ↵

- Moseley, J. B., O’Malley, K., Petersen, N. J., Menke, T. J., Brody, B. A., Kuykendall, D. H., … Wray, N. P. (2002). A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347 , 81–88. ↵

A type of study designed specifically to answer the question of whether there is a causal relationship between two variables.

The variable the experimenter manipulates.

The variable the experimenter measures (it is the presumed effect).

The different levels of the independent variable to which participants are assigned.

Holding extraneous variables constant in order to separate the effect of the independent variable from the effect of the extraneous variables.

Any variable other than the dependent and independent variable.

Changing the level, or condition, of the independent variable systematically so that different groups of participants are exposed to different levels of that variable, or the same group of participants is exposed to different levels at different times.

An experiment design involving a single independent variable with two conditions.

When an experiment has one independent variable that is manipulated to produce more than two conditions.

An extraneous variable that varies systematically with the independent variable, and thus confuses the effect of the independent variable with the effect of the extraneous one.

Any intervention meant to change people’s behavior for the better.

The condition in which participants receive the treatment.

The condition in which participants do not receive the treatment.

An experiment that researches the effectiveness of psychotherapies and medical treatments.

The condition in which participants receive no treatment whatsoever.

A simulated treatment that lacks any active ingredient or element that is hypothesized to make the treatment effective, but is otherwise identical to the treatment.

An effect that is due to the placebo rather than the treatment.

Condition in which the participants receive a placebo rather than the treatment.

Condition in which participants are told that they will receive the treatment but must wait until the participants in the treatment condition have already received it.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

What is an Experiment? An experiment is an investigation in which a hypothesis is scientifically tested. An independent variable (the cause) is manipulated in an experiment, and the dependent variable (the effect) is measured; any extraneous variables are controlled.

n. a series of observations conducted under controlled conditions to study a relationship with the purpose of drawing causal inferences about that relationship.

What Is the Experimental Method in Psychology? The experimental method involves manipulating one variable to determine if this causes changes in another variable. This method relies on controlled research methods and random assignment of study subjects to test a hypothesis.

Experimental psychology is a branch of psychology that utilizes scientific methods to investigate the mind and behavior. It involves the systematic and controlled study of human and animal behavior through observation and experimentation.

Experimental psychology is able to shed light on people’s personalities and life experiences by examining what the way people behave and how behavior is shaped throughout life, along with other theoretical questions.

Experimental psychology, a method of studying psychological phenomena and processes. The experimental method in psychology attempts to account for the activities of animals (including humans) and the functional organization of mental processes by manipulating variables that may give rise to.

Experimental psychology refers to work done by those who apply experimental methods to psychological study and the underlying processes.

Definition of experiment: An experiment in psychology is when there is a study conducted that investigates the direct effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable. Tip: If you’re not sure if it’s an experiment, you’re always safe to call it a “study.”

Experimental psychologists conduct experiments to learn more about why people do certain things. Why do people do the things they do? What factors influence how personality develops? And how do our behaviors and experiences shape our character?

What Is an Experiment? As we saw earlier in the book, an experiment is a type of study designed specifically to answer the question of whether there is a causal relationship between two variables.