The Wason Selection Task

You've got bored of working for a card games manufacturer, and you're now working as a security executive in a bar (you're a bouncer). It's your job to ensure that the rule governing the consumption of alcohol is strictly enforced. It states:

If a person drinks an alcoholic drink, then they must be over the age of 21 years old.

The cards below reprsent the drink of choice and age of four customers at your bar. (Each card represents one person: one side shows what they're drinking - note the card on the left shows beer, the alcoholic kind! - the other side their age.) Please indicate which card or cards you definitely need to turn over, and only that or those cards, in order to determine whether the rule is broken in the case of each of the four customers. (To indicate that it is necessary to turn over a card, simply "select" the card by clicking in the little box beneath it.)

************

After you've made your selection(s), click the Submit button below to find out how you've done in the test.

Question 3 of 3

Really Deep Thought

Psychology in Action

Psychology classics: wason selection task (part i).

This post is the first of three on the Wason selection task ( Part II ), and part of our ongoing series exploring classic experiments and theories in the history of psychological research . In the 1960s, Peter Cathcart Wason introduced a test of logical reasoning that he termed the selection task (1966, 1968, 1969a, 1969b). Almost fifty years later, the Wason selection task is still a source of much research and debate, albeit not quite in the way he had originally intended. Introduced as a test of his theory of confirmation bias , Wason’s task has ended up a widely used experimental paradigm for examining human reasoning in the domains of abstract logic, social conduct, and various other semantic contexts. The task has become contentious in cognitive science research, but it is still commonly studied today due to the fact that people’s performance demonstrates a striking content effect , although the psychological account of when and how this phenomenon occurs has been continually revised over the last few decades. Before going any further, let’s try Wason’s original version (1966):

You are shown these four green cards and given the following prompt:

Wason selection task: Abstract

You are told these four cards have a letter on one side and a number on the other. You are given a rule about the four cards: If a card has a vowel on one side, then it has an even number on the other side . You are asked, which card(s) do you need to turn over in order to determine if the rule is true or false ?

[expand title=”Click here to show typical results for this experiment.”] This abstract form of the Wason selection task generally yields the following distribution of answers (Wason & Shapiro, 1971): ~ 45% pick the A card and the 4 card ~ 35% pick the A card alone ~ 7% pick the A card, 4 card, and the 7 card ~ 4% pick the A card and the 7 card [ correct ] ~ 9% pick other combinations of cards [/expand] The shocking thing about Wason’s results is that the logically correct (normative) answer is only chosen by about 4% of subjects (Wason & Shapiro, 1971). Although subjects clearly recognize the importance of selecting the A card, it is logical to select the 7 card as well, because in the event that it has a vowel on the other side, the rule would be violated (thus falsified). Conversely, there is no logical reason to select the 4 card because it is not possible for it to falsify the rule––whether there is a vowel or a consonant on the other side is irrelevant as there is no restriction on an even-consonant pair.

A bit of logic

In order to more precisely characterize subjects’ logical reasoning, it’s worthwhile to summarize a few bits of formal logic. First, the logical structure intended in Wason selection tasks is a simple conditional ––that is, an “if P then Q ” statement. When it comes to the logical form of a conditional, P → Q , we call proposition P the antecedent and proposition Q the consequent (the thing that follows from the antecedent). We can either affirm (state as true) or deny (state as false) either of the propositions, thus there are four simple argument structures that could be applied. Two of these arguments are logically valid (their conclusion will always be true if their premises are true), and the other two are logically invalid (their conclusion can be false even if their premises are true).

Table 1 : Valid and Invalid Arguments for Conditional Logic

Affirming the Antecedent ( modus ponens )

1. P → Q 2. P

Denying the Consequent ( modus tollens )

1. P → Q 2. ~ Q

Affirming the Consequent (INVALID)

1. P → Q 2. Q

Denying the Antecedent (INVALID)

1. P → Q 2. ~ P

Table 1 shows the four simple arguments for P → Q , with their conclusions below the lines. The more obvious of the valid arguments is Affirming the Antecedent, which is called modus ponens . Clearly, if the premise P → Q is true, and we know P is true, then it follows that Q is true. The much trickier valid argument, which is most relevant to the effects we see in the Wason selection task, is Denying the Consequent ( modus tollens ). If we know that Q follows from P , but we know Q is false, then working backwards, P must also be false (or else Q would have been true). The validity of this argument becomes more apparent when we (validly) rearrange the conditional into its contrapositive form: ~ Q → ~ P , at which point we can use modus ponens to conclude ~ P from ~ Q (where ~ X is read “not X “).

Wason’s subjects overwhelmingly failed to apply modus tollens , an important method of falsification. In order to fully assess whether the rule is true or false, one must look for the presence of P when there is an absence of Q , because the contrapositive requires there be no P if there is no Q . A simpler way to put this is that the only possible way to falsify the rule is to find a card with P on one side and ~ Q on the other side; thus, only cards showing a P or ~ Q are worth checking .

The content effect

In 1971, Wason and his doctoral student, Diana Shapiro, published a study demonstrating that participants still struggled with the abstract form of the task (even after being given a practice abstract problem to learn from). However, they were much more likely to give the modus tollens (~ Q ) response on an isomorphic thematic (semantic) version of the task. Subjects evaluated the rule “Every time I go to Manchester I travel by car,” using cards with cities on one side and modes of transport on the other. The explanation for the improved performance was that while the British participants wouldn’t have experience reasoning about relations between even numbers and vowels, they would have experience with traveling by car or train to cities in the UK, which facilitated their reasoning.

Because the two problems were written such that underlying logical structure was (presumably) equivalent across conditions, Wason and Shapiro (1971) argued that the improved performance on the thematic version was evidence of a semantic , not syntactic , effect. However, this in and of itself was not all that surprising––they acknowledged that the increased salience of ‘concrete’ terms, in line with prior research, might make them easier to symbolically manipulate and reason about. In a similar thematic experiment, Wason’s former student, Philip Johnson-Laird, along with Italian psychologists Paolo and Maria Legrenzi, (1972) tested British subjects on a form of the selection task using a rule about the value of postage stamps necessary to send a letter in a closed or open envelope (there was a lower postage rate for unsealed mail). Again, researchers believed that familiarity with the problem context helped them identify and reason normatively about the underlying logical structure, thus increasing the modus tollens responses.

Over the next decade came a series of seemingly contradictory results, such as Griggs and Cox’s (1982) failure to replicate Wason and Shapiro’s (1971) and Johnson-Laird et al.’s (1972) results using the same problem contexts (travel and postage) with American subjects. Golding (1981) used a similar postage rule that had actually been used in Britain (but had since been abandoned) and showed facilitation in older British subjects (who would have had experience with the old rule), but not younger subjects. Taken altogether, these results indicated an important role of prior experience with the content of a rule, especially instances of counterexamples ( P & ~ Q ), leading some researchers to posit that reasoners typically don’t use general rules of inference, but rather draw from domain-specific memories of relevant counterexamples (Griggs & Cox, 1982; Manktelow & Evans, 1979). This so-called “memory-cueing” hypothesis stated that rather than facilitating the normative logical structure, domain-specific familiarity merely allowed participants to access their memory of counterexamples, obviating the need for domain-general logic.

Here is a classic example of a concrete Wason selection task with a rule most Americans should be familiar with (adapted from Griggs & Cox, 1982):

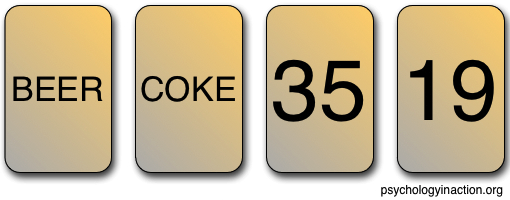

You are shown these four orange cards and given the following prompt:

Wason selection task: Thematic

You are told these four cards represent patrons in a bar, and each card has their drink on one side and their age in years on the other. You are given a rule about the four patrons: If a patron is drinking a beer, then they must be 21 years or older . You are asked, which card(s) do you need to turn over in order to determine if the rule is being followed?

[expand title=”Click here to show typical results for this experiment.”] This permission-schema (alcohol) form of the Wason selection task generally yields the following distribution of answers (Griggs & Cox, 1982, Exp. 3):

~ 0% pick the BEER card and the 35 card ~ 20% pick the BEER card alone ~ 3% pick the BEER card, 35 card, and the 19 card ~ 72% pick the BEER card and the 19 card [ correct ] ~ 5% pick other combinations of cards [/expand]

It seems unsurprising that people would understand that in this bar context, one would need to check a 19-year-old to make sure they weren’t drinking. It’s likely that subjects are familiar with the concept of alcohol laws and underaged drinking, and would readily recognize that a 19-year-old could potentially violate the rule whereas a 35-year-old could not. This is an instance in which subjects readily reason by modus tollens , because the contrapositive of the rule (“If you are NOT 21 years or older, then you must NOT be drinking beer”) seems much more obvious than the contrapositive in the abstract case (and certain other thematic domains). One reason for this difference is that subjects would not have personal experience with, for example, the abstract vowel-even number context from Problem 1, such that subjects would not be able to pull up a relevant memory to arrive at the normatively logical solution.

But the memory-cueing theory would not last long, because it was soon found that performance could be facilitated in contexts for which most people would not have had specific experience (e.g., a certain system of monitoring sales receipts in a department store; D’Andrade, 1982). Reasoners seem to be able to draw on some sort of more general knowledge––more abstract than specific memories but less abstract than formal logic.

In the next post on the Wason selection task, I will discuss the two popular theories that emerged in the 1980s and generated a new wave of interest in research with the task. Stay tuned for more!

Update: Part II

D’Andrade, R. (1982, April). Reason versus logic . Paper presented at the Symposium on the Ecology of Cognition: Biological, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives, Greensboro, NC.

Golding, E. (1981). The effect of past experience on problem solving. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the British Psychological Society, Surrey University.

Griggs, R. A., & Cox, J. R. (1982). The elusive thematic-materials effect in Wason’s selection task. British Journal of Psychology, 73 , 407–420.

Johnson-Laird, P., Legrenzi, P., & Legrenzi, M. S. (1972). Reasoning and a sense of reality. British Journal of Psychology , 63 (3), 395–400.

Manktelow, K. I., & Evans, J. St. B. T. (1979). Facilitation of reasoning by realism: Effect or non-effect? British Journal of Psychology, 70 , 477–488.

Wason, P. C. (1966). Reasoning. In B. Foss (Ed.), New horizons in psychology (pp. 135–151). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Wason, P. C. (1968). Reasoning about a rule. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 20 , 273–281.

Wason, P. C. (1969a). Structural simplicity and psychological complexity: Some thoughts on a novel problem. Bulletin of the British Psychological Society, 22 , 281–284.

Wason, P. C. (1969b). Regression in reasoning? British Journal of Psychology, 60 , 471–480.

Wason, P. C., & Shapiro, D. (1971). Natural and contrived experience in a reasoning problem. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology , 23 , 63–71.

Making Sense of Wason

Parallel mentalistic/mechanistic cognition resolves the controversy..

Updated November 6, 2024 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

One of the longest-running debates in modern psychology centers on the correct interpretation of the Wason Selection Task. Peter Wason originally designed the test to see if people applied logic that would disprove a hypothesis by falsifying it as well as by confirming it. It goes like this:

Imagine that you have the job of checking that cards have been sorted correctly. You have to make sure that, if a person has a "D" on one side of a card, they have a "3" on the other. The four below have to be checked to see if they conform . Which card or cards do you definitely have to turn over in order to see if it violates the rule?

Less than one in four people get this right. Most people either choose D and 3, or D alone. The correct answer is D and 7. The reason is that the rule says simply that a card with a D on one side must have a 3 on the other, not that a card with a 3 must have a D on the other side. So whether the 3 has a D on its back or not is irrelevant. However, it is important to know what is on the other side of the 7, because, if that were a D, the rule would be violated, and the correction would have to be made.

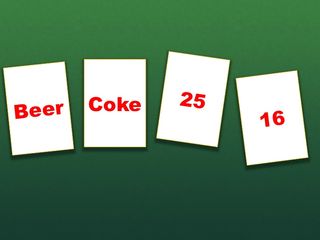

Now consider a second situation:

You are serving at a bar and have to enforce the rule that if a person is drinking beer, they must be over 20 years of age. The four cards below have information about people sitting at a table. One side of the card tells you what a person is drinking and the other side tells their age. Which card or cards must you turn over to see if the rule is being broken?

The correct answer is the cards with beer and 16. However, about 75 percent of people get this one right. Why is this so when only one in four get the previous version right? How is it that people are seemingly more intelligent with drinks and ages of drinkers than with letters and numbers?

The evolutionary psychologists, Cosmides and Tooby,* claim that both tests are logically exactly the same, but that in the second one, a “cheat-detection” mental module kicks in which helps people to get it right most of the time. They argue that the problem with enforcing the law about the drinking age is a “social contract” issue that mobilizes the cheat-detection module of the mind to get the answer right in the majority of cases. However, if cheat-detection is not involved, as it isn't with the card-checking problem, most people get the answer wrong.

Evolutionary psychologists often give the impression that this conclusion is widely accepted in the Wason-testing community. But in fact, this is not the case. On the contrary, an alternative explanation is that in the second example it is immediately apparent that a person who is 16 years old may be violating the rule. However, in the first case, it is not obvious until you think about it that the rule which says that a card with D on one side must have a 3 on the other also means that a card with any number other than 3 must be checked to see if the letter on its other side violates the rule. In spite of a superficial similarity, these are simply different tasks. Indeed, some believe that reasoning is not involved in the selection task at all, which is much more a question of judging the relevance of the information presented, as the following example of the test illustrates:

The City Council has asked for volunteers to take care of visiting school children. Volunteers have to fill in a card. Rossi and Bianchi, two clerks of the City Council, are about to sort the cards. There are two scenarios:

Scenario A. Bianchi believes that only women will volunteer, but Rossi asserts that there are male volunteers. Bianchi bets Rossi that all the male volunteers are married, and Rossi accepts the bet. Cards filled in by the volunteers show sex on one side and marital status on the other. Because sex and marital status are on different sides of the card, it is impossible to find out if Bianchi has won the bet without turning over one or more cards.

Your task is to decide which card or cards it is absolutely necessary for Rossi to turn over in order to see if Bianchi has won the bet that if a volunteer is male, then he is married. The four cards are:

Scenario B. Bianchi bets that men with dark hair will volunteer to take the children and Rossi accepts the bet. Cards filled in by the volunteers show sex on one side and hair color on the other. In front of the clerks on the table are four cards.

Your task is to decide which card or cards it is absolutely necessary for Rossi to turn over in order to see if Bianchi has won the bet that if a volunteer is male, he has dark hair. The four cards are:

Thirty-six undergraduates at the University of Padua took part in the experiment and were randomly assigned scenarios A or B. The correct answers are cards 1 and 4 in both scenarios. However, only 16 percent got the right answer in scenario B, while 65 percent got it right in scenario A. Sperber, Cara, and Girotto interpret this finding to prove that the relevance of information to the selection task is more important than any other factor. For example, in this case, marital status is often relevant to childcare, whereas hair color never is.

However, these findings also cast doubt on Cosmides and Tooby’s claim that a specific “cheat-detection module” is involved because there is no question of deception in either case, and both versions are logically and semantically the same.

Nevertheless, the cheat-detection versus social-relevance interpretations can be reconciled as stressing different aspects of mentalistic cognition . Detecting cheating is an obvious aspect of mentalism understood as interpersonal, psychological interaction, as indeed is putting things in their correct social context and judging their relevance accordingly. The original, purely abstract version of the Wason Selection Task, by contrast, epitomizes mechanistic cognition. Indeed, the latter is something you can imagine a computer being programmed to do very readily. But serving drinks at a bar or assigning school children in the other two examples could not be entrusted to machines because both rely on good social skills, common-sense, and contextual understanding of people’s behavior: in a word, mentalism. And because people are people and not machines, the mentalistic versions of the Wason Task are easy, and the original, mechanistic version, hard.

An obvious implication is that autistics — or at least high functioning ones — ought to do worse on the cheat-detection Wason Task than normal thanks to their symptomatic deficits in mentalism. A paper published in 2009** claiming to be the first to do so compared 20 autistics with 20 non- autistic controls matched for age, sex, and IQ on a Wason test involving intentional versus unintentional cheating. The autistics did indeed do worse than the controls on both, but showed exactly the same 30 percent difference between the intentional versus the unintentional cheating scenarios: controls 80/50 percent correct on intentional cheating/unintentional cheating; autistics 60/30 percent.

The researchers offer their own explanations, but my prediction is that if tested on the non-cheating, social relevance version of the Wason Task above, the autistics would do worse still. This is because autistics are good at rule-learning and rule-enforcement — often naively and very literally so, thanks to their mentalistic deficits and tendency to think mechanistically. This may explain their relative success with scenarios involving the detection of cheating, which is always a question of breaking a rule or acting unfairly in some way. Clearly, more research is needed, but it would help if researchers were aware that the Wason Task findings might in fact hinge on the difference between mechanistic and mentalistic modes of cognition .

* Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. Cognitive Adaptations for Social Exchange. in The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture (eds. Barkow, J.H., Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J.) pp. 163-228 (Oxford University Press, New York, 1992).

** Rutherford, M.D. & Ray, D. Cheater Detection is Preserved in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Social, Evolutionary and Cultural Psychology 3, 105-117 (2009).

Christopher Robert Badcock, Ph.D. , is the author of The Imprinted Brain: How Genes Set the Balance Between Autism and Psychosis.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Centre

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- Calgary, AB

- Edmonton, AB

- Hamilton, ON

- Montréal, QC

- Toronto, ON

- Vancouver, BC

- Winnipeg, MB

- Mississauga, ON

- Oakville, ON

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

When we fall prey to perfectionism, we think we’re honorably aspiring to be our very best, but often we’re really just setting ourselves up for failure, as perfection is impossible and its pursuit inevitably backfires.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Psychology Labs and Resources

Department of psychology.

- Lab Information

- Lab Access Form

- Psychology Equipment

- Psychometric Tests & Tools

- PsychoPy Experiment Bank

- Stimulus Banks

- PsychoPy Builder

- Lab Manuals & Software

- Participant Scheme (SONA)

Wason Selection Task

Description.

The Wason selection task (or four-card problem) is a logic puzzle devised by Peter Cathcart Wason in 1966. It is one of the most famous tasks in the study of deductive reasoning.

Wason, P. C. (1968). "Reasoning about a rule". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 20 (3): 273–281. doi:10.1080/14640746808400161

Wason (1966) Selection Task

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 15 October 2018

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Ken Manktelow 3

291 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

The four-card problem ; The Wason selection task ; Wason’s four-card problem ; Wason’s selection task

The Wason (1966) selection task is a reasoning task based on the logic of conditional rules and their violation.

Wason’s selection task is a problem designed to explore the ways people reason with conditional statements, those that can be expressed using “if.” It is one of a suite of reasoning problems invented by the British psychologist Peter Wason (1924–2003) and arose from his interest in, and curiosity about, firstly, the use of conditionals in both everyday and official language and, secondly, a tendency he had uncovered in earlier research using another of his tasks for people to confirm their beliefs rather than test them through attempted falsification. (This story is detailed in Wason and Johnson-Laird 1972 , a monograph reviewing the authors’ early work on reasoning.) Wason ( 1964 ) had previously observed that experimental participants did not adhere to the...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Brown, W. & Moore, C. (2000). Is prospective altruist-detection an evolved solution to the adaptive problem of subtle cheating in cooperative ventures? Supportive evidence using the Wason selection task. Evolution and human behavior, 21 , 25–37.

Article Google Scholar

Cheng, P. W., & Holyoak, K. J. (1985). Pragmatic reasoning schemas. Cognitive Psychology, 17 , 391–416.

Cheng, P. W., & Holyoak, K. J. (1989). On the natural selection of reasoning theories. Cognition, 33 , 285–313.

Cohen, L. J. (1981). Can human irrationality be experimentally demonstrated? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 4 , 317–370.

Cosmides, L. (1989). The logic of social exchange: Has natural selection shaped how humans reason? Studies with the Wason selection task. Cognition, 31 , 187–316.

Cummins, D. D. (1996). Evidence of deontic reasoning in 3- and 4-year-old children. Memory & Cognition, 24 , 823–829.

Fiddick, L. (2004). Domains of deontic reasoning: Resolving the discrepancy between the cognitive and moral reasoning literatures. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 57A , 447–474.

Fiddick, L., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2000). No interpretation without representation: The role of representations and inferences in the Wason selection task. Cognition, 77 , 1–79.

Gigerenzer, G., & Hug, K. (1992). Domain-specific reasoning: Social contracts, cheating and perspective change. Cognition, 43 , 127–171.

Girotto, V., Blaye, A., & Farioli, F. (1989). A reason to reason: Pragmatic bases of children’s search for counterexamples. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 9 , 227–231.

Google Scholar

Griggs, R. A., & Cox, J. R. (1982). The elusive thematic-materials effect in Wason’s selection task. British Journal of Psychology, 73 , 407–420.

Hiraishi, K., & Hasegawa, T. (2001). Sharing-rule and detection of free-riders in cooperative groups: Evolutionarily important deontic reasoning in the Wason selection task. Thinking & Reasoning, 7 , 255–294.

Johnson-Laird, P. N., Legrenzi, P., & Legrenzi, M. S. (1972). Reasoning and a sense of reality. British Journal of Psychology, 63 , 395–400.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow . London: Allen Lane.

Kirby, K. N. (1994). Probabilities and utilities of fictional outcomes in Wason’s four-card selection task. Cognition, 51 , 1–28.

Manktelow, K. I. (2012). Thinking and reasoning: An introduction to the psychology of reason, judgment and decision making . London/New York: Psychology Press.

Manktelow, K. I., & Evans, J. St. B.T. (1979). Facilitation of reasoning by realism: Effect or non-effect? British Journal of Psychology, 70 , 477–488.

Manktelow, K. I., & Over, D. E. (1990). Deontic thought and the selection task. In K. Gilhooly, M. Keane, R. Logie, & G. Erdos (Eds.), Lines of thought: Reflections on the psychology of thinking (Vol. 1). Chichester: Wiley.

Manktelow, K. I., & Over, D. E. (1991). Social roles and utilities in reasoning with deontic conditionals. Cognition, 39 , 85–105.

Manktelow, K. I., Sutherland, E. J., & Over, D. E. (1995). Probabilistic factors in deontic reasoning. Thinking & Reasoning, 1 , 201–220.

O’Brien, D. P. (1995). Finding logic in human reasoning requires looking in the right places. In S. E. Newstead & J. St. B.T. Evans (Eds.), Perspectives on thinking and reasoning: Essays in honour of Peter Wason . Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Over, D. E. (Ed.). (2003). Evolution and the psychology of thinking: The debate . London/New York: Psychology Press.

Sperber, D., Cara, F., & Girotto, V. (1995). Relevance theory explains the selection task. Cognition, 57 , 31–95.

Stenning, K., & van Lambalgen, M. (2008). Human reasoning and cognitive science . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology, 46 , 35–57.

Wason, P. C. (1964). The effect of self-contradiction on fallacious reasoning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 16 , 30–34.

Wason, P. C. (1966). Reasoning. In B. M. Foss (Ed.), New horizons in psychology 1 . Harmondsworth: Pelican.

Wason, P. C. (1968). Reasoning about a rule. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 20 , 273–281.

Wason, P. C. (1969). Structural simplicity and psychological complexity. Bulletin of the British Psychological Society, 22 , 281–284.

Wason, P. C., & Evans, J. St. B. T. (1975). Dual processes in reasoning? Cognition, 3 , 141–154.

Wason, P. C., & Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1970). A conflict between selecting and evaluating information in an inferential task. British Journal of Psychology, 61 , 509–515.

Wason, P. C., & Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1972). Psychology of reasoning: Structure and content . London: Batsford.

Wason, P. C., & Shapiro, D. A. (1971). Natural and contrived experience in a reasoning task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 23 , 63–71.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Emeritus Professor of Psychology, University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton, UK

Ken Manktelow

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ken Manktelow .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA

Todd K. Shackelford

Rochester, MI, USA

Viviana A. Weekes-Shackelford

Section Editor information

Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Kevin Kniffin

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Manktelow, K. (2019). Wason (1966) Selection Task. In: Shackelford, T., Weekes-Shackelford, V. (eds) Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_3439-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_3439-1

Received : 25 September 2018

Accepted : 07 October 2018

Published : 15 October 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-16999-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-16999-6

eBook Packages : Living Reference Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

COMMENTS

That's got to be easy, right? Well maybe, but the Wason Selection Task, as it is called, is one of the most oft repeated tests of logical reasoning in the world of experimental psychology. So let's see how you do. There are three questions to complete, each one associated with a set of four cards. Here's the first question.

The Wason Selection Task. Question 2. You're still working as a quality control technician for a card games manufacturer (it's a good job!). But now you have to check a different rule: If a card has the letter S on one side, then it has the number 3 on the other side.

The Wason selection task (or four-card problem) is a logic puzzle devised by Peter Cathcart Wason in 1966. [1] [2] [3] It is one of the most famous tasks in the study of deductive reasoning. [4] An example of the puzzle is: You are shown a set of four cards placed on a table, each of which has a number on one side and a color on the other.

The Wason Selection Task. Question 3. You've got bored of working for a card games manufacturer, and you're now working as a security executive in a bar (you're a bouncer). It's your job to ensure that the rule governing the consumption of alcohol is strictly enforced. It states:

Oct 7, 2012 · This post is the first of three on the Wason selection task , and part of our ongoing series exploring classic experiments and theories in the history of psychological research. In the 1960s, Peter Cathcart Wason introduced a test of logical reasoning that he termed the selection task (1966, 1968, 1969a, 1969b). Almost fifty years later, the ...

The original, purely abstract version of the Wason Selection Task, by contrast, epitomizes mechanistic cognition. Indeed, the latter is something you can imagine a computer being programmed to do ...

Nov 19, 2024 · PsychoPy Experiment Bank; Stimulus Banks; Qualtrics; PsychoPy Builder; Lab Manuals & Software; Participant Scheme (SONA) Wason Selection Task Download Task Description. The Wason selection task (or four-card problem) is a logic puzzle devised by Peter Cathcart Wason in 1966. It is one of the most famous tasks in the study of deductive reasoning.

Oct 15, 2018 · The selection task made its debut in a book chapter (Wason 1966) and was quickly taken up by researchers around the world: in 1974, a whole conference on it was held in Italy, and it is now common to refer to it as the most, or one of the most, often-used experimental paradigms in the field, “the mother of all reasoning tasks,” in the words ...

The Wason (1966) selection task is a reasoning task based on the logic of conditional rules and their violation. Wason’s selection task is a problem designed to explore the ways people reason with condi-tional statements, those that can be expressed using “if.” It is one of a suite of reasoning prob-lems invented by the British ...

The original Wason (1968) version of this experiment is discussed in Chapter 10 of your textbook (deductive reasoning). How many people get the letter and number version WRONG in Wason's original data?