- For Ophthalmologists

- For Practice Management

- For Clinical Teams

- For Public & Patients

Museum of the Eye

- Museum Home

- Group Tours

- Museum Galleries

- Special Exhibitions

- Current Events

- Past Events

- Research & Resources

- Collection Search

- Online Exhibits

- Oral Histories

- Legacy Project

- Biographies

- Mailing List

- About the Museum

- Eye Witness Blog

- Museum Media Kit

- Museum of the Eye® /

- Eye Openers™

- Eye Diagram

- How Do You See?

- How Does the Eye Focus?

- Activity: Name the Parts of the Eye

- Binocular Vision

- Experiment: Different Views

Experiment: Hole In Your Hand

- Experiment: Blind Spot

What Are Optical Illusions?

- Experiment: Optical Illusions

- Moving Pictures

- Activity: Make a Spinning Disc

- Activity: Make A Flipbook

Purpose: To locate and identify the blind spot

Length of Activity: 20 minutes

- One 3 x 5 inch card (or other stiff paper) per student.

- Black markers.

- 1 ruler per student.

1. Students should be instructed to make a dot and an X on the white side of the index card as pictured.

2. They should then hold the card so the X is on the right side and raise it to eye level about an arm's length away.

3. Have students close their right eye.

4. Student should look directly at the X with their left eye only. They should note that they can also see the dot, but should not focus on it.

5. While looking at the X, and keeping an awareness of the dot, have students bring the cards slowly towards their faces. At some point they should be aware that the dot has disappeared and then reappeared.

6. Now have students repeat but this time close their left eyes. They should use their right eyes to look at the dot while keeping aware of (but not looking directly at) the X. This time the X will disappear and then reappear as the card is slowly brought towards their faces.

7. Now have students take their markers and ruler to draw a straight line through the center of both the dot and the X.

8. Repeat the activity. Note that this time the line seems to be continuous, with no gap, even as the X or dot disappears.

What’s Going On?

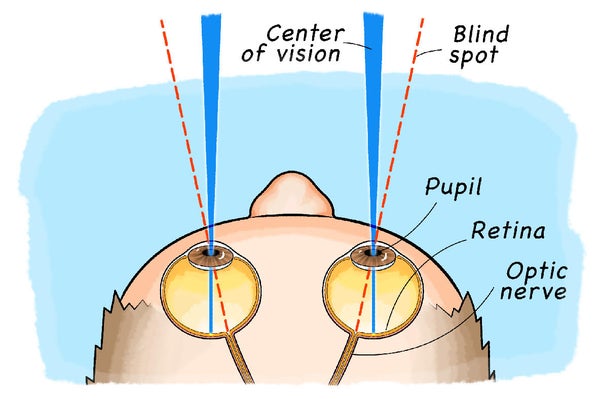

At the back of your eye is the retina. Your retina is made up of light-sensitive cells which send messages to your brain about what you see. Everyone has a spot in their retina where the optic nerve connects. In this area there are no light-sensitive cells so this part of your retina can’t see. We call this the blind spot. The point at which the mark on the card disappears is where your blind spot is.

When you draw a line through the dot and X you set up an optical illusion. The brain knows that a line is there and fills in the gap, even as it loses sight of the dot or X.

All content on the Academy’s website is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service . This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

- About the Academy

- Jobs at the Academy

- Financial Relationships with Industry

- Medical Disclaimer

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Statement on Artificial Intelligence

- For Advertisers

- Ophthalmology Job Center

FOLLOW THE ACADEMY

Medical Professionals

Public & Patients

January 30, 2020

Find Your Blind Spot!

A visual science project from Science Buddies

By Science Buddies & Svenja Lohner

Now you see it... Try this simple activity to locate your own blind spots.

George Retseck

Key Concepts Biology Physiology Senses Vision Perception

Introduction Did you know that you have a blind spot in each of your eyes? This doesn't mean you see a constant black spot in your field of vision. Normally you don't notice these blind spots at all. There are, however, some ways you can make these blind spots come to light, so to speak! This activity will show you how to find them.

Background Our eyes are complex organs that allow us to detect visual objects, colors, motion and other things happening around us. To be able to see, however, we need light. Usually what we see is light that reflects off of objects and then enters our eyes through the pupil (the pupil is the opening in the middle of the front of the eye). How much light gets into the eye is controlled by the iris, which is the colored part around the pupil that can contract and expand to open and close the pupil. Inside the eye the light lands on the retina at the back of the eye, which is a light-sensitive layer of tissue. The retina has two types of light-sensing cells: rods and cones. Rods provide black-and-white vision in dim light whereas the cones are responsible for color vision.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

When light hits the rod and cone cells, nerve impulses are triggered and sent to the brain through the optic nerve. In humans and most vertebrates the optic nerve fibers pass through the retina and out of the back of the eyeball. The area where the bundled nerve fibers pass through the retina does not contain any light sensitive cells. This means we don't see light that hits this exact spot. Although we technically cannot see this light, our brain can usually fill in the information that we are missing based on the other things around the blind spot. This is the reason why we don't usually notice our blind spots. In this activity, however, you will see how under certain circumstances your blind spot can seem to make things disappear. Are you ready to make your blind spot visible?

Cardstock paper

Ruler or measuring tape

Pen or pencil

Preparation

Carefully cut a 2-inch-high and 5-inch-long rectangle from the cardstock paper.

Place the paper rectangle on a surface so that it is lying long-ways (2 inches high and 5 inches wide).

By the left edge of the paper, halfway between the top and bottom, draw a small shape (no wider than 0.5 inches) such as a circle, heart or plus sign.

By the right edge, halfway between the top and bottom, draw another shape of approximately the same size.

Take the rectangle in your right hand. Hold it in the middle so you can see both shapes.

Extend your arm with the rectangle at eye level. Focus your eyes on the left shape. With your eyes still focused on the left shape can you still see the shape on the right side of the paper?

Slowly move your extended arm closer to your face. While moving the paper closer keep your eyes focused on the left shape. While moving the paper can you still see both shapes clearly?

Cover your left eye with your left hand. Extend the right arm with the paper at eye level again. Focus your right eye on the left shape. Can you see the other shape as well?

With your left eye covered and your right eye focusing on the left shape, slowly move the paper closer toward your face. Keep focusing your right eye on the left shape. What happens to the shape on the right side of the paper while you move the paper closer?

Now cover your right eye with your right hand. Extend your left arm with the paper, and look at the right shape. Are you able to still see the left shape while focusing on the right shape with your left eye?

Again slowly move the paper closer to you. Keep your left eye focused on the right shape. What do you notice this time?

Extra: Draw a horizontal line straight across the paper from one edge to the other, running through your two shapes. Repeat the activity. How do your results change?

Extra: Can you measure the size of your blind spot? Cover one of your eyes, and position the paper at a distance where one of the shapes disappears from your vision. Move a pen across the paper and mark where it disappears in your blind spot from all sides. The markings allow you to measure the size of your blind spot in your field of vision.

Extra: Make a new paper card, but this time draw bigger shapes on each side. Does the activity still work?

Observations and Results Did you find your blind spot? When looking at the paper rectangle with both eyes you probably always saw both shapes on each side of the paper—even when you moved your arm closer to your body. When you looked with only your right eye directly at the left shape, however, you should have noticed that at some point the right shape disappeared as you moved the paper closer to your face. At this position the shape just happened to be in your blind spot. This blind spot is there because the optic nerve fibers pass through the back of your retina inside your eye. Where the nerve passes through there are no cells receiving light. At this tiny spot, which is approximately the size of a pinhead, you are technically blind. You know that you have such a blind spot in both of your eyes because you should have seen the same thing happen when you looked at the right shape with your left eye. This time the left shape should have disappeared.

If you did the extra activity with the straight line across the card, you should have noticed that the shape still disappeared but you still saw a continuous straight line all the way to the edge of the paper. This is a great example of how your brain tries to fill in the blanks of the blind spot. Your brain noticed the straight line in the area surrounding your blind spot—and just continued the line even though it technically didn't detect it there. The brain, however, couldn't notice the shape because it was fully inside the blind spot. As a result the shape disappeared, but the straight line was still visible.

More to Explore Sight and the Eye , from Ducksters Why Do I Have a Blind Spot in My Eye? , from Healthline We've All Got a Blind Spot, But It Can Be Shrunk , from Science Daily Put Your Peripheral Vision to the Test , from Scientific American STEM Activities for Kids , from Science Buddies

This activity brought to you in partnership with Science Buddies

IMAGES