- Privacy Policy

Home » Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Table of Contents

Observational research is a method of data collection where researchers observe participants in their natural settings without interference or manipulation. Unlike experimental research, which relies on controlling variables, observational research captures data as it unfolds naturally, making it an invaluable method for studying real-world behaviors, interactions, and environments. This approach is particularly useful in social sciences, anthropology, psychology, and marketing, providing insights into complex phenomena in authentic contexts.

Observational Research

Observational research is a qualitative research method involving the systematic observation and recording of behaviors, actions, and interactions. It allows researchers to gather detailed, context-rich data directly from participants or environments, rather than relying on self-reports or controlled experiments.

Key Characteristics of Observational Research :

- Non-Intrusive : Observes participants without altering their environment.

- Qualitative Focus : Emphasizes detailed, descriptive data, though quantitative methods can also be used.

- Natural Settings : Conducted in real-world locations where participants normally exist, such as schools, workplaces, or homes.

- Flexible : Allows researchers to adapt observations based on unexpected events or behaviors.

Example : Observing customer behavior in a retail store to understand purchasing decisions and engagement with product displays.

Methods of Observational Research

Observational research methods can be divided into several types based on the level of involvement of the researcher and the structure of the observations. The four main types are participant observation , non-participant observation , structured observation , and unstructured observation .

1. Participant Observation

Definition : In participant observation, the researcher actively participates in the environment being studied. By engaging with participants and experiencing the setting firsthand, researchers gain an in-depth perspective on group dynamics and behaviors.

Purpose : To gain a deeper understanding of social contexts by immersing in the environment and developing relationships with participants.

Example : A sociologist joins a workplace team as an employee to study organizational culture and employee interactions.

Advantages :

- Provides rich, detailed data and insights.

- Builds trust with participants, encouraging open behavior.

Disadvantages :

- May lead to researcher bias.

- Time-consuming and may influence participant behavior.

2. Non-Participant Observation

Definition : In non-participant observation, the researcher observes participants without actively engaging or influencing the environment. This approach minimizes bias by maintaining the researcher as an outsider, simply observing and recording data.

Purpose : To objectively observe behaviors without influencing participants or intervening in their environment.

Example : A psychologist observes children playing at a park to study social behavior without interacting with them.

- Minimizes observer influence on participants.

- Enables objective, unbiased observations.

- Limited depth of understanding compared to participant observation.

- May miss subtle contextual details without interaction.

3. Structured Observation

Definition : Structured observation involves using a predefined framework or checklist to systematically record specific behaviors or events. This method is often quantitative, as it focuses on observing and counting occurrences of certain behaviors.

Purpose : To collect data on specific behaviors in a controlled, standardized manner.

Example : In a classroom setting, a researcher observes how many times students raise their hands during a lesson to gauge engagement.

- Allows for replicability and consistency across observations.

- Simplifies data analysis by using a structured format.

- May overlook unexpected or nuanced behaviors.

- Limits flexibility to adapt observations based on context.

4. Unstructured Observation

Definition : Unstructured observation does not follow a strict framework; instead, the researcher observes behaviors freely, noting anything deemed relevant to the study. This method allows for flexibility and adaptability to capture rich, qualitative data.

Purpose : To explore behaviors and interactions without restrictions, capturing comprehensive insights into complex phenomena.

Example : An anthropologist observes a tribal ceremony, taking notes on customs, gestures, and interactions without a predefined checklist.

- Provides comprehensive, in-depth data.

- Captures unexpected behaviors and interactions.

- Data can be challenging to analyze due to lack of structure.

- Subjectivity may lead to researcher bias.

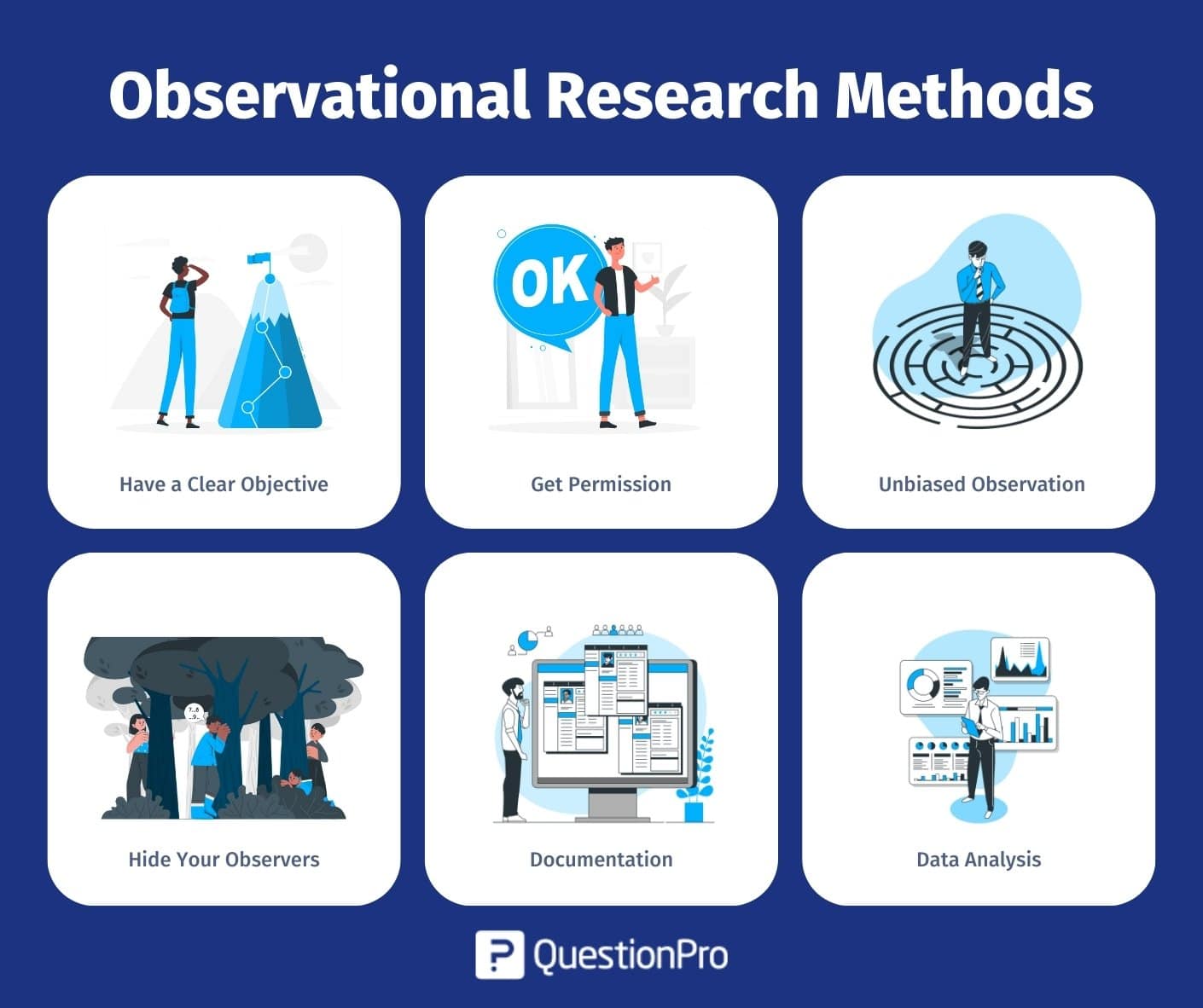

Guide to Conducting Observational Research

Step 1: define the research objective.

Start by clearly defining the purpose of your research. Establish the research question or objective that guides the observational study, ensuring it aligns with the chosen observation method.

Example : For a study on customer satisfaction, the objective might be to observe customer interactions with staff in a retail environment.

Step 2: Choose the Observation Type

Select the type of observation that best fits the research objective. Consider factors such as the level of involvement, structure, and setting needed to answer the research question effectively.

Example : Structured observation may be ideal for counting specific customer behaviors, while unstructured observation may work better for exploring general customer experiences.

Step 3: Select the Observation Site and Participants

Identify the location and participant group to observe. If necessary, obtain permission to observe in specific settings, especially if it’s a private or controlled environment.

Example : Choose a retail store to observe customer-staff interactions, or select a particular demographic of customers for focused observation.

Step 4: Prepare Data Collection Tools

For structured observation, prepare a checklist or framework that specifies which behaviors or interactions to observe and record. Unstructured observation may require a journal or voice recorder for detailed note-taking.

Example : A checklist could include metrics like “number of customer inquiries” or “time spent engaging with a product.”

Step 5: Conduct the Observation

Begin the observation by immersing yourself in the environment, whether as a participant or observer. Take detailed notes on behaviors, interactions, and environmental factors that may be relevant to the research objective.

- Maintain a non-intrusive presence to reduce observer influence on participants.

- Capture as much detail as possible, even if it seems irrelevant, to provide context during analysis.

Step 6: Record Observations and Data

Use appropriate methods to record observations. Structured observations may involve tally sheets or digital devices to count occurrences, while unstructured observations may require detailed field notes or audio recordings.

Example : For participant observation, the researcher might write down field notes each day, describing interactions, behaviors, and context.

Step 7: Analyze Data

Depending on the type of observation, analyze the data for patterns, themes, or frequencies of specific behaviors. Quantitative data from structured observations can be statistically analyzed, while qualitative data from unstructured observations can be coded for thematic analysis.

Example : A researcher might use statistical software to analyze frequency counts, or qualitative software like NVivo for thematic analysis of unstructured data.

Step 8: Interpret Findings

Draw conclusions based on the observed data, linking them back to the research objectives. Consider how the observations provide insights into the research question, and address any limitations or potential biases.

Example : Observing that customer satisfaction improves with staff engagement may support the hypothesis that staff interaction is key to a positive shopping experience.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Observational Research

- Realistic Insights : Observes behaviors in natural settings, providing authentic data.

- Context-Rich Data : Captures details that other methods may miss, providing a fuller picture.

- Flexible and Adaptive : Unstructured observation allows researchers to adjust their focus based on emerging behaviors.

Disadvantages

- Observer Bias : Researcher expectations or interpretations may influence observations.

- Time-Consuming : Observation can require extensive time to capture sufficient data.

- Limited Control : Lack of control over variables can make it challenging to isolate specific factors.

Tips for Effective Observational Research

- Stay Objective : Minimize personal biases by focusing on factual details rather than subjective interpretations.

- Be Consistent : For structured observations, adhere to the checklist or framework to ensure reliable data.

- Record Contextual Information : Document details about the setting, time, and environmental factors that may influence observations.

- Use Multiple Observers if Possible : Involving multiple researchers can increase reliability and reduce bias.

- Practice Ethical Observation : Ensure participants’ privacy and confidentiality, especially in settings where informed consent is required.

Ethical Considerations in Observational Research

Ethical considerations are essential, particularly when observing people in sensitive environments or private settings. Researchers should:

- Obtain Consent : Seek permission to observe in private settings, and inform participants about the study when appropriate.

- Ensure Confidentiality : Avoid identifying specific individuals in reports to maintain privacy.

- Minimize Harm : Avoid interfering with the participants’ natural behaviors or environment.

Observational research is a valuable method for studying natural behaviors, interactions, and environments. By carefully selecting the type of observation, defining objectives, and employing ethical practices, researchers can gain insights that other methods may not provide. Whether structured or unstructured, observational research allows for in-depth exploration of complex phenomena, making it an essential approach in fields like psychology, anthropology, education, and market research.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social Research Methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Angrosino, M. (2007). Doing Ethnographic and Observational Research . SAGE Publications.

- Silverman, D. (2016). Qualitative Research (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Bernard, H. R. (2017). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (6th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Transformative Design – Methods, Types, Guide

Applied Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types...

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

15 Participant Observation Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Participant observation is research method where the researcher not only observes the research subjects, but also actively engages in the activities of the subjects (Musante & DeWalt, 2010; Kawulich, 2005). They are both observing and participating .

This method is particularly useful in the social sciences, where researchers aim to understand complex socio-cultural phenomena from an insider’s view. This can involve long-term immersion in the field to gather detailed and nuanced data.

Participant Observation Examples

1. Workplace Observation A researcher studying the dynamics of a corporation might take a job within the company. This way, they can observe the corporate culture, hierarchies, office dynamics, and interactions in their natural settings from an employee’s perspective.

Sample Study: Among the agilists: participant observation in a rapidly evolving workplace

Brief Explanation: This participant observation study discussed in this paper focused on researchers embedding themselves within an agile software development community. They aimed to understand how this community works and evolves over time. The researchers used methods like interviews and close interaction to gain insights.

Citation: Kumar, S., & Wallace, C. (2016, May). Among the agilists: participant observation in a rapidly evolving workplace. In Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Cooperative and Human Aspects of Software Engineering (pp. 52-55).

2. Cultural Immersion A researcher moves to a foreign country or unfamiliar community, immersing themselves in the new culture. They observe social customs, languages, and day-to-day activities to understand the group’s socio-cultural practices.

3. Formal or Informal Group Meetings A researcher might participate in group meetings (civic organizations, religious bodies, support groups, etc.) to observe group dynamics, decision-making processes, or the impacts and implementation of collective regulations.

4. Online Groups A researcher might join an online community, game, or forum to understand the virtual behaviors, online social interactions, dynamics, etiquette, and patterns. This is often a part of ‘digital ethnography’.

Sample Study: Legitimate Peripheral Participation by Novices in a Dungeons and Dragons Community

Brief Explanation: This participant observation study focused on how new players learn to join the Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) community and culture. The researchers watched and interviewed both experienced and new players to understand how novices become part of the D&D world. They found that some novices needed in-game training to learn their roles, while others quickly learned by participating in online communities and watching games. The study showed that becoming a part of the D&D community involves both playing at the table and engaging with the wider online D&D world.

Citation: Giordano, M. J. (2022). Legitimate Peripheral Participation by Novices in a Dungeons and Dragons Community. Simulation & Gaming , 53 (5), 446-469.

5. Police Work A researcher may ride along with police officers to observe their day-to-day activities, decision-making processes , and their interactions with the community.

6. Homeless Community A researcher might spend time incognito in homeless communities to observe first-hand the struggles, social norms, coping mechanisms, and the impact of local policies on these communities.

7. Religious Festivals A researcher participates in religious festivals or public ceremonies to understand the associated cultural symbols, rituals, conduct, and beliefs.

8. Healthcare Settings A researcher could embed themselves in a hospital or clinic to observe interactions between healthcare providers and patients, to understand patient-care protocols, or assess workflow efficiency.

Sample Study: Participant observation in obesity research with children

Brief Explanation: This participant observation study was about researching obesity in children by observing them in their everyday activities. The researchers wanted to understand how children think about food and their bodies. They found that talking to children through regular interviews might limit their responses. Instead, by watching children in their natural environments, the researchers gained better insights into how children view their bodies and health. This approach allowed them to see beyond the typical spaces where research is done and understand children’s experiences more deeply.

Citation: Gunson, J. S., Warin, M., Zivkovic, T., & Moore, V. (2016). Participant observation in obesity research with children: Striated and smooth spaces. Children’s Geographies , 14 (1), 20-34.

9. Subculture Observation A researcher might immerse themselves in a particular subculture, such as biker clubs, punk or goth communities, or online fandoms, to observe their practices, codes, relationship dynamics, and shared identities.

10. Sporting Events A researcher could join a soccer league, a boxing gym, or an extreme sports club to examine the dynamics, customs, procedures, and participant motivation within these organizations.

11. Ethnobotany Study A researcher could join a community in a remote location to study their use of plants for medicinal, nutritional, and other purposes, their knowledge transfer methodologies, and associated cultural practices.

12. Educational Settings A researcher might participate as a teacher or a student in a classroom to understand teaching methods, student behavior, the impact of classroom environments on learning, or the effectiveness of certain educational policies.

Sample Study: The place of humor in the classroom

Brief Explanation: This study looked at humor in classrooms, specifically how much and what kind of humor teachers and students use. The study explored both positive and negative effects of humor, as inappropriate humor can be bad. The researchers were participant observes in 105 Greek primary school classrooms and found that teachers used humor about twice per teaching hour on average.

Citation: Chaniotakis, N., & Papazoglou, M. (2019). The place of humor in the classroom. Research on young children’s humor: Theoretical and practical implications for early childhood education , 127-144.

13. Consumer Behavior A researcher might pose as a shopper in a retail store to observe and understand consumer behavior, shopping habits, influences on purchasing decisions, effectiveness of product placements, and impacts of store environments on consumer choices.

14. Campaign Observation A researcher may join a political or social campaign to observe the strategies utilized, the internal structures and conduct, and the dynamics of public engagement.

15. Prison Settings A researcher might work as a guard or administrator in a prison setting to study the attitudes, behaviors, and interactions of inmates and prison staff.

Pros and Cons of Participant Observation

- Generation of rich and detailed data: Participant observation allows the researcher to collect data that is in-depth and rich in detail due to the firsthand experience (Balsiger & Lambelet, 2014; Gunn & Logstrup, 2014). The researcher can record observations, feelings, and interpretations, capturing the complexity of human behavior and providing a context for understanding it.

- The naturalistic and real-world context: In participant observation, data is collected in the natural environment of the subject, thus providing a more realistic picture of what is being studied. Observations are less artificial than controlled settings, such as in laboratory experiments (Spradley, 2016; Musante & DeWalt, 2010).

- Flexibility: The researcher has the ability to adjust the research focus as the study progresses. If during the course of observation, the researcher identifies new aspects of the research question or encounters new paths of enquiry, there is the possibility to explore these (Spradley, 2016).

- Insider perspective: By participating actively in the group or community being observed, the researcher acquires an internal perspective, thus gaining access to the members’ perceptions, values, and views which might not surface through other research methods (Kawulich, 2005).

- Risk of subjectivity: Personal biases and the involvement of the researcher in the group being studied can lead to the observed behavior being interpreted subjectively (Jorgensen, 2020). The researcher’s presence might alter the research environment and the behavior of those being observed, which could further influence the data’s validity.

- Time and resource intensity: The participant observation method often requires the researcher to spend a large amount of time in the field. It may also necessitate the learning of a new language or culture, or it can involve travel and accommodation expenses, if the observation is taking place in a different region (Lambelet, 2014; Jorgensen, 2020).

- Difficulties in replication: Since the observations are not only determined by the observed phenomena and participants, but also the unique interpretation of the observer, replication of studies can be very difficult (Jorgensen, 2020).

- Ethical considerations: There can be ethical dilemmas, such as concerns about privacy and informed consent. In participant observation, the line between observing and participating can sometimes blur, potentially leading to ethical dilemmas if subjects do not know they are part of a study (Musante & DeWalt, 2010).

- Problem of data overload: Participant observations can generate a significant amount of data, including personal observations, conversations, interviews, and documents, presenting a challenge when it comes to data management, coding, and analysis (Spradley, 2016). As a result, effectively synthesizing all the available information can pose a significant complication.

Participant Observation vs Ethnography

Participant observation generally occurs in the social sciences during qualitative field research . The participant enters the setting, participates and observes, then leaves.

However, an extended version of participant observation, where the participant remains immersed in the setting for a sustained period of time, is called ethnography (Spradley, 2016).

While the two methods overlap, there are some key differences, explored below:

- Participant Observation: This approach involves a researcher immersing themselves in a social setting and observing behaviors, interactions, events, and activities (Jorgensen, 2020; Kawulich, 2005). The researcher participates in the activities to a certain extent to better understand the group or culture while also maintaining a level of detachment, often entering and leaving settings.

- Ethnography: This is a broader research method that often includes participant observation, but goes further, where the researcher becomes a member of the group for a sustained period of time. This provides an in-depth ‘thick description’ of everyday life and practices. The goal of ethnography is to understand the social world in the same way as the people being studied. It typically involves a variety of data collection methods such as interviews, surveys, and document analysis, in addition to participant observation.

Overall, while participant observation focuses on observation and participation in certain activities, ethnography seeks to provide a broader cultural context and deep understanding of the socio-cultural phenomena at play.

Participant observation is a useful tool for qualitative research, often generating richer insights than quantitative research or even other qualitative methods like interviewing alone. It can be done in a range of settings, including workplace, school, religious, cultural, and even prison settings! Overall, it’s useful for helping researchers to dig beneath the surface, but does have drawbacks such as lack of generalizability and researcher subjectivity.

Balsiger, P., & Lambelet, A. (2014). Participant observation: how participant observation changes our view on social movements. Methodological practices in social movement research , 144-172.

Chaniotakis, N., & Papazoglou, M. (2019). The place of humor in the classroom. Research on young children’s humor: Theoretical and practical implications for early childhood education , 127-144.

Giordano, M. J. (2022). Legitimate Peripheral Participation by Novices in a Dungeons and Dragons Community. Simulation & Gaming , 53 (5), 446-469.

Gunn, W., & Logstrup, L. B. (2014). Participant observation, anthropology methodology and design anthropology research inquiry. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education , 13 (4), 428-442.

Gunson, J. S., Warin, M., Zivkovic, T., & Moore, V. (2016). Participant observation in obesity research with children: Striated and smooth spaces. Children’s Geographies , 14 (1), 20-34.

Jorgensen, D. L. (2020). Principles, approaches and issues in participant observation . Routledge.

Kawulich, B. B. (2005, May). Participant observation as a data collection method. In Forum qualitative sozialforschung/forum: Qualitative social research (Vol. 6, No. 2).

Kumar, S., & Wallace, C. (2016, May). Among the agilists: participant observation in a rapidly evolving workplace. In Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Cooperative and Human Aspects of Software Engineering (pp. 52-55).

Musante, K., & DeWalt, B. R. (2010). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers . Rowman Altamira.

Spradley, J. P. (2016). Participant observation . Waveland Press.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Free Social Skills Worksheets

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

1 thought on “15 Participant Observation Examples”

Your references have been useful to me and have provided me with invaluable insight and knowledge on my topic of interest. I am extremely grateful for your assistance and appreciate the time and effort

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Qualitative Observation: Examples, Types, and Methods Explained

Explore key examples, types, and effective methods of qualitative observation in research.

Want to understand what your customers really think and feel? Then you’re in the right place. We’re going to introduce you to qualitative observation.

We’ll also cover the different types, benefits, and methods of qualitative research, plus we’ll show you step-by-step how to conduct your own observations in the wild.

But first, a favorite quote from one of our favorite researchers:

“Qualitative research is more important than ever. AI does not replace it and in fact it will increasingly need what it is that people are doing who are on this call today. And the most important thing we can do is make sure we stay the course and say humanity deserves the attention that UX research has to offer it’s core to anything we’re going to do that’s meaningful.” Mary Gray, Senior Principal Researcher at Microsoft

Ready to streamline your qualitative research and unlock deeper insights? Request a free demo of Marvin’s powerful tools.

What is a Qualitative Observation?

Qualitative observation is a form of research in which you use your senses—sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing—to observe the behaviors of your subjects in their natural setting.

Rather than relying on cold, hard data, qualitative observation focuses on the observer’s subjective “feelings” about the situation. It’s often used by psychologists, animal behavioral scientists, healthcare professionals, marketers, and educators to gather real-world experiences.

Here’s an example of qualitative research you might be familiar with…

Imagine you’re the principal at a local high school and want to evaluate a teacher’s performance. What would you do?

You’d probably sit in on their class and observe their tone of voice, facial expressions, and interactions with the class. Based on these observations, you would then make inferences , like “ the kids love when she makes jokes” or “ his students clearly understand the material by the end of the class.”

That’s qualitative observation in action.

The benefits of gaining this type of subjective insight include:

- Gaining deep insight into customer behavior

- Improving communication with customer segments by improving messaging

- Enhancing curriculum design

- Obtaining a better understanding of behaviors and social interactions

- Improving services and public policies for educators, therapists, healthcare workers, and businesses

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Observations

Important note: Understanding the difference between qualitative research vs. quantitative research is crucial.

Qualitative observation relies on using your senses to make observations and describe the qualities of a phenomenon.

Quantitative observation uses statistical data rather than relying on your senses. It’s best for situations where you need to test hypotheses, measure trends, evaluate data, compare data sets, or implement quality control.

Depending on the task, researchers may combine both quantitative and qualitative observations to reach their goal. This is called a mixed-method approach.

Types of Observation in Qualitative Research

Let’s start by understanding the different types of qualitative research. This should help you build an action plan for conducting your first observation.

Participant Observation

Participant observation is when you actively engage in the environment you’re studying rather than observing from the sidelines. This allows you to see your subjects in a natural setting and gather data you’d never otherwise get.

Think of it like going undercover. The secret here is that the others can’t know you are the researcher. As soon as they know, they will act differently around you. We cover more about this phenomenon (the Hawthorne Effect) in our Challenges section.

For example, a retail company might have a manager work on the sales floor to understand customer interactions and identify areas for improvement.

Non-participant Observation

Non-participant observation is the opposite of participant observation — you sit on the sidelines as a neutral observer, watching your subjects go about their business without interfering.

Non-participant observations are best for studying:

- Employees in the office

- Students in a classroom

- Human behavior in a social setting

- Customer behavior in a store

When you aren’t actively participating in the research, you have more time to focus on recording observations. It also maintains the integrity of the group since you aren’t influencing the behaviors of your subjects at all.

Structured Observation

Structured observation is a method of research where the observer uses a predefined framework for observing their subjects, such as checklists or rating scales.

This type of organized research is best used in tandem with quantitative research.

For example, someone observing a classroom might use an observation framework that rates the teacher’s tone of voice, relationship with students, and delivery of the materials. This data could then be used alongside quantitative research to measure their performance over time or compare it to other departments.

Unstructured Observation

Unstructured observation is a “hands-off” style of monitoring subjects where the researcher just watches and records anything they feel is relevant.

This is an open-ended, flexible style of observation that doesn’t use a framework. Normally, in unstructured observation, the researcher will take detailed notes or record video that they can analyze later.

Pro tip: Freestyle observation is best during the early stages of research. Say you want to improve customer care in a healthcare setting. You might start with unstructured observation and note how patients and their families interact with staff. You could then use these notes to define critical goals and create an evaluation framework.

What Are the Key Methods of Qualitative Observation?

To gather rich data by watching people in action, researchers use various techniques:

- Direct Observation. Direct observation is when you watch your subjects in their natural environment without getting in the way. This lets you see real behaviors in real time, so you can gather authentic data.

- Interviews. Interviews let you explore the “why” behind customer behaviors. Researchers love interviews because they can dig deeper to get context and depth that observation alone can’t. ( By the way, Marvin is amazing for this!)

- Inductive Reasoning. Inductive reasoning lets you gather observations, notice patterns, and then build a theory from the ground up. You draw conclusions based on what you experience.

- Understanding Context. Understanding context emphasizes the importance of the “big picture” and how the environment or social connections between people or events affect the outcomes. In a nutshell, you can’t just look at the raw data without understanding the data’s context.

- Subjectivity. This might surprise you, but having your own subjective experiences helps you ask better questions, empathize with your subjects, and analyze the data more efficiently. Your subjective experience is your strength!

How to Conduct a Qualitative Observation

Now that you know what qualitative observation is, the different types of observations you can conduct, and the methods behind the madness, let’s get into how to actually use it to make business decisions ( without wasting a ton of time and money) .

Step 1: Define Your Purpose

What’s the whole point of this observation anyway? You aren’t just sitting around watching live recordings of customers on your website all day for no reason. Write down what you want to learn from this observation, and be as specific as possible .

For example, we’re going to pretend we’re an e-commerce company conducting research on how to improve conversions on our checkout pages. We should define our purpose like this:

“We want to understand why users aren’t converting on our seasonal checkout pages.” NOT, “We are going to observe user behavior on our website.”

Step 2: Define Your Setting and Choose Your Role

Where is this observation going to take place? In a classroom, on the street, on the web? Make sure you know the who, where, and how of your research before you start. This includes defining your role as the researcher, too. Will you actively participate in the research or observe from the sidelines?

Refer to the section above on different types of observations. In our example, the e-commerce company decided to conduct non-participant observation to observe visitors using their website in real time.

Step 3: Plan Your Methodology

How are you going to observe the participants in your study? Are you going to use a rating scale? Will it be totally freestyle with just a notepad? Are you going to watch 14 hours of customer interactions using HotJar? Are you going to collect the data using Marvin and then have your team of researchers share the data with each other (hint, hint!)?

In this case, our fictional e-commerce company chose tools like HotJar and Marvin to record visitor interaction, then store the data in a location that’s easily accessible to all team members. They also came up with a list of criteria for evaluating the user’s behavior on each page.

Step 4: Execute

It’s time to watch some visitor behavior videos. Fire up your software and grab some popcorn. As you watch each video, use your set criteria to evaluate each interaction and observe why people aren’t buying your eco-friendly clothes.

Be mindful of bias and context as you’re watching.

Step 5: Organize and Analyze

This is when you store the data using software ( if it’s online) and begin to figure out the how and why behind things. Maybe your buttons aren’t the right colors. Maybe the price is too high. Or maybe your web copy isn’t any good. We don’t know your store, so we can’t say why. (Actually wait, this store is fictional, so nobody really knows.)

Once you’ve made your observations, it’s important to build a hypothesis based on the data and start testing.

Qualitative research is an iterative, scientific process. For instance, if people aren’t even getting to your call-to-action buttons, then you probably need to test the web copy and placement of your CTAs.

Since it’s iterative, you probably want a great tool to track all your data, observations, and insights. Mozey on over to this article I wrote about how AI makes qualitative research powerful.

Or hit the super-easy button and sign up for a free Marvin account .

Examples of Qualitative Observation

Here are two examples of how researchers use qualitative observations in real-life situations.

Qualitative Observation in Retail

Have you heard of mystery shopping?

Large retailers often hire people who secretly wander stores to observe employees “in the wild” and take note of the customer experience.

This type of qualitative observation offers incredible insight for retailers, such as how employees are performing and how the company could improve its customer experience.

Qualitative Observation in Education

Just in case you still haven’t recovered from the memories of our 2020 lockdown, let’s bring that sore spot up again.

COVID-19 drove everyone indoors, spawning a massive increase in remote learning. But did kids really learn anything sitting at home and learning via Zoom?

School districts conducted interviews with kids, parents, and educators to learn how effective it was. What did they like or dislike? Were the students engaged during lessons? Did test scores improve? How was student attendance?

What a lot of schools found was that as long as kids had a quiet space dedicated to learning, they performed just fine.

Key Challenges in Conducting Qualitative Observation

Qualitative analysis based on subjective human experiences is extremely nuanced. Sometimes, companies even ignore context and subjectivity altogether, which can lead to poor decisions that end up reducing ROI rather than improving it.

So, keep an eye out for a few challenges…

- Bias. Qualitative analysis is fraught with people seeking confirmation bias. That is, we look for information that merely confirms our previously existing opinions or hypotheses rather than conducting open-minded research. Always consider how your own biases—or those of other researchers—may influence the notes, data, insights, or action steps.

- The Hawthorne Effect. People act differently when they know they’re being watched, which reduces the effectiveness of research. This can be a real problem during user interviews — participants often skew toward more positive answers when asked directly about a product. Using multiple research methods can help you confirm their answers against tangible data.

- Inconsistency. It’s not easy to systemize and analyze thousands of unique observations in different settings. This is where research design and a standardized protocol come into play (wherever applicable). Researchers often create their own framework for studying groups or analyzing data. Sometimes, they review data with peers using a coding system to get a more concrete picture of what’s really happening.

- Inaccurate Data. Data accuracy is a major challenge in qualitative analysis because it is subjective, interpretive, and context-dependent. Use strategies like triangulation — combining multiple data sources or methods to cross-check findings.

The good news? There are plenty of tools designed to improve qualitative observation and analysis. Marvin’s sophisticated AI research assistant automates most of the tasks listed above, which decreases manual errors and speeds up your entire workflow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

In case you still have questions, here are a few more answers.

What Skills Are Essential for Effective Qualitative Observation?

Key skills include attention to detail, remaining objective, and strong note-taking abilities. You also need to be patient, a good listener, and open-minded.

It’s also important to be able to interpret what you observe without jumping to conclusions.

What Are Common Tools Used in Qualitative Observation?

Common tools include notebooks or digital devices for taking detailed notes, audio or video recorders for capturing interactions, and sometimes observation checklists to ensure consistency.

Software like NVivo, Marvin, or HotJar can also be used to organize and analyze the data you collect.

Can Qualitative Observation be Conducted Remotely?

Yes, qualitative observation can be conducted remotely, especially with the help of video conferencing tools, session recordings, or virtual environments.

It’s not the same as in-person observation, but you can still gather valuable insights by watching how people interact in digital spaces.

How to Know if Quantitative or Qualitative Observation is More Suitable for a Study?

Quantitative observation is better suited for measuring and comparing specific variables, like numbers or percentages. But if you need to understand behaviors, experiences, or the “why” behind actions, qualitative observation is better.

Think about whether you need numbers or a deeper understanding to decide which approach fits your study.

Now that you know what qualitative observation is, how it works, how to conduct it, and the challenges you’ll face, it’s time to devise a plan and start gathering data.

What do you want to study? How are you going to study it? And which tools are you going to use?Follow the blueprint we’ve given you here and start building your toolkit for conducting research. If you want an AI-driven tool for collecting, storing, analyzing, and sharing data for qualitative research, request a demo of Marvin today.

Categories:

- Leading the Way

- Marvin Customers

- Marvin Events

- Talk to Your Users

- qualitative research

Related Articles

Qualitative Data Analysis: Methods, Tools, and FAQs Included

(6 Top Picks) Survey Analysis Software – Complete Guide

(Top 8) Best Qualitative Data Analysis Software

- Roxanne Rosewood

- Latest posts

Roxanne Rosewood is a seasoned UX researcher who is passionate about helping users shape the future of products. She leverages her expertise to uncover user insights that inform product design and development. Beyond research, Roxanne shares her knowledge through insightful blog posts about UX design and research on theroxanneperspective.com. She also mentors upcoming UX designers and researchers, fostering the next generation of user experience professionals.

- 7 Best Customer Insight Tools for Data Analysis (Compared)

- From User Insights to Action: How AI Makes Qualitative Research Powerful

withemes on instagram

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

7.6: Observational Research

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 224150

- Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton

- Kwantlen Polytechnic U., Washington State U., & Texas A&M U.—Texarkana

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- List the various types of observational research methods and distinguish between each.

- Describe the strengths and weakness of each observational research method.

What Is Observational Research?

The term observational research is used to refer to several different types of non-experimental studies in which behavior is systematically observed and recorded. The goal of observational research is to describe a variable or set of variables. More generally, the goal is to obtain a snapshot of specific characteristics of an individual, group, or setting. As described previously, observational research is non-experimental because nothing is manipulated or controlled, and as such we cannot arrive at causal conclusions using this approach. The data that are collected in observational research studies are often qualitative in nature but they may also be quantitative or both (mixed-methods). There are several different types of observational methods that will be described below.

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observation is an observational method that involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. Thus naturalistic observation is a type of field research (as opposed to a type of laboratory research). Jane Goodall’s famous research on chimpanzees is a classic example of naturalistic observation. Dr. Goodall spent three decades observing chimpanzees in their natural environment in East Africa. She examined such things as chimpanzee’s social structure, mating patterns, gender roles, family structure, and care of offspring by observing them in the wild. However, naturalistic observation could more simply involve observing shoppers in a grocery store, children on a school playground, or psychiatric inpatients in their wards. Researchers engaged in naturalistic observation usually make their observations as unobtrusively as possible so that participants are not aware that they are being studied. Such an approach is called disguised naturalistic observation. Ethically, this method is considered to be acceptable if the participants remain anonymous and the behavior occurs in a public setting where people would not normally have an expectation of privacy. Grocery shoppers putting items into their shopping carts, for example, are engaged in public behavior that is easily observable by store employees and other shoppers. For this reason, most researchers would consider it ethically acceptable to observe them for a study. On the other hand, one of the arguments against the ethicality of the naturalistic observation of “bathroom behavior” discussed earlier in the book is that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy even in a public restroom and that this expectation was violated.

In cases where it is not ethical or practical to conduct disguised naturalistic observation, researchers can conduct undisguised naturalistic observation where the participants are made aware of the researcher presence and monitoring of their behavior. However, one concern with undisguised naturalistic observation is reactivity. Reactivity refers to when a measure changes participants’ behavior. In the case of undisguised naturalistic observation, the concern with reactivity is that when people know they are being observed and studied, they may act differently than they normally would. This type of reactivity is known as the Hawthorne effect . For instance, you may act much differently in a bar if you know that someone is observing you and recording your behaviors and this would invalidate the study. So disguised observation is less reactive and therefore can have higher validity because people are not aware that their behaviors are being observed and recorded. However, we now know that people often become used to being observed and with time they begin to behave naturally in the researcher’s presence. In other words, over time people habituate to being observed. Think about reality shows like Big Brother or Survivor where people are constantly being observed and recorded. While they may be on their best behavior at first, in a fairly short amount of time they are flirting, having sex, wearing next to nothing, screaming at each other, and occasionally behaving in ways that are embarrassing.

Participant Observation

Another approach to data collection in observational research is participant observation. In participant observation , researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying. Participant observation is very similar to naturalistic observation in that it involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. As with naturalistic observation, the data that are collected can include interviews (usually unstructured), notes based on their observations and interactions, documents, photographs, and other artifacts. The only difference between naturalistic observation and participant observation is that researchers engaged in participant observation become active members of the group or situations they are studying. The basic rationale for participant observation is that there may be important information that is only accessible to, or can be interpreted only by, someone who is an active participant in the group or situation. Like naturalistic observation, participant observation can be either disguised or undisguised. In disguised participant observation, the researchers pretend to be members of the social group they are observing and conceal their true identity as researchers.

In a famous example of disguised participant observation, Leon Festinger and his colleagues infiltrated a doomsday cult known as the Seekers, whose members believed that the apocalypse would occur on December 21, 1954. Interested in studying how members of the group would cope psychologically when the prophecy inevitably failed, they carefully recorded the events and reactions of the cult members in the days before and after the supposed end of the world. Unsurprisingly, the cult members did not give up their belief but instead convinced themselves that it was their faith and efforts that saved the world from destruction. Festinger and his colleagues later published a book about this experience, which they used to illustrate the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Riecken, & Schachter, 1956) [1] .

In contrast with undisguised participant observation, the researchers become a part of the group they are studying and they disclose their true identity as researchers to the group under investigation. Once again there are important ethical issues to consider with disguised participant observation. First no informed consent can be obtained and second deception is being used. The researcher is deceiving the participants by intentionally withholding information about their motivations for being a part of the social group they are studying. But sometimes disguised participation is the only way to access a protective group (like a cult). Further, disguised participant observation is less prone to reactivity than undisguised participant observation.

Rosenhan’s study (1973) [2] of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward would be considered disguised participant observation because Rosenhan and his pseudopatients were admitted into psychiatric hospitals on the pretense of being patients so that they could observe the way that psychiatric patients are treated by staff. The staff and other patients were unaware of their true identities as researchers.

Another example of participant observation comes from a study by sociologist Amy Wilkins on a university-based religious organization that emphasized how happy its members were (Wilkins, 2008) [3] . Wilkins spent 12 months attending and participating in the group’s meetings and social events, and she interviewed several group members. In her study, Wilkins identified several ways in which the group “enforced” happiness—for example, by continually talking about happiness, discouraging the expression of negative emotions, and using happiness as a way to distinguish themselves from other groups.

One of the primary benefits of participant observation is that the researchers are in a much better position to understand the viewpoint and experiences of the people they are studying when they are a part of the social group. The primary limitation with this approach is that the mere presence of the observer could affect the behavior of the people being observed. While this is also a concern with naturalistic observation, additional concerns arise when researchers become active members of the social group they are studying because that they may change the social dynamics and/or influence the behavior of the people they are studying. Similarly, if the researcher acts as a participant observer there can be concerns with biases resulting from developing relationships with the participants. Concretely, the researcher may become less objective resulting in more experimenter bias.

Structured Observation

Another observational method is structured observation . Here the investigator makes careful observations of one or more specific behaviors in a particular setting that is more structured than the settings used in naturalistic or participant observation. Often the setting in which the observations are made is not the natural setting. Instead, the researcher may observe people in the laboratory environment. Alternatively, the researcher may observe people in a natural setting (like a classroom setting) that they have structured some way, for instance by introducing some specific task participants are to engage in or by introducing a specific social situation or manipulation.

Structured observation is very similar to naturalistic observation and participant observation in that in all three cases researchers are observing naturally occurring behavior; however, the emphasis in structured observation is on gathering quantitative rather than qualitative data. Researchers using this approach are interested in a limited set of behaviors. This allows them to quantify the behaviors they are observing. In other words, structured observation is less global than naturalistic or participant observation because the researcher engaged in structured observations is interested in a small number of specific behaviors. Therefore, rather than recording everything that happens, the researcher only focuses on very specific behaviors of interest.

Researchers Robert Levine and Ara Norenzayan used structured observation to study differences in the “pace of life” across countries (Levine & Norenzayan, 1999) [4] . One of their measures involved observing pedestrians in a large city to see how long it took them to walk 60 feet. They found that people in some countries walked reliably faster than people in other countries. For example, people in Canada and Sweden covered 60 feet in just under 13 seconds on average, while people in Brazil and Romania took close to 17 seconds. When structured observation takes place in the complex and even chaotic “real world,” the questions of when, where, and under what conditions the observations will be made, and who exactly will be observed are important to consider. Levine and Norenzayan described their sampling process as follows:

“Male and female walking speed over a distance of 60 feet was measured in at least two locations in main downtown areas in each city. Measurements were taken during main business hours on clear summer days. All locations were flat, unobstructed, had broad sidewalks, and were sufficiently uncrowded to allow pedestrians to move at potentially maximum speeds. To control for the effects of socializing, only pedestrians walking alone were used. Children, individuals with obvious physical handicaps, and window-shoppers were not timed. Thirty-five men and 35 women were timed in most cities.” (p. 186).

Precise specification of the sampling process in this way makes data collection manageable for the observers, and it also provides some control over important extraneous variables. For example, by making their observations on clear summer days in all countries, Levine and Norenzayan controlled for effects of the weather on people’s walking speeds. In Levine and Norenzayan’s study, measurement was relatively straightforward. They simply measured out a 60-foot distance along a city sidewalk and then used a stopwatch to time participants as they walked over that distance.

As another example, researchers Robert Kraut and Robert Johnston wanted to study bowlers’ reactions to their shots, both when they were facing the pins and then when they turned toward their companions (Kraut & Johnston, 1979) [5] . But what “reactions” should they observe? Based on previous research and their own pilot testing, Kraut and Johnston created a list of reactions that included “closed smile,” “open smile,” “laugh,” “neutral face,” “look down,” “look away,” and “face cover” (covering one’s face with one’s hands). The observers committed this list to memory and then practiced by coding the reactions of bowlers who had been videotaped. During the actual study, the observers spoke into an audio recorder, describing the reactions they observed. Among the most interesting results of this study was that bowlers rarely smiled while they still faced the pins. They were much more likely to smile after they turned toward their companions, suggesting that smiling is not purely an expression of happiness but also a form of social communication.

In yet another example (this one in a laboratory environment), Dov Cohen and his colleagues had observers rate the emotional reactions of participants who had just been deliberately bumped and insulted by a confederate after they dropped off a completed questionnaire at the end of a hallway. The confederate was posing as someone who worked in the same building and who was frustrated by having to close a file drawer twice in order to permit the participants to walk past them (first to drop off the questionnaire at the end of the hallway and once again on their way back to the room where they believed the study they signed up for was taking place). The two observers were positioned at different ends of the hallway so that they could read the participants’ body language and hear anything they might say. Interestingly, the researchers hypothesized that participants from the southern United States, which is one of several places in the world that has a “culture of honor,” would react with more aggression than participants from the northern United States, a prediction that was in fact supported by the observational data (Cohen, Nisbett, Bowdle, & Schwarz, 1996) [6] .

When the observations require a judgment on the part of the observers—as in the studies by Kraut and Johnston and Cohen and his colleagues—a process referred to as coding is typically required . Coding generally requires clearly defining a set of target behaviors. The observers then categorize participants individually in terms of which behavior they have engaged in and the number of times they engaged in each behavior. The observers might even record the duration of each behavior. The target behaviors must be defined in such a way that guides different observers to code them in the same way. This difficulty with coding illustrates the issue of interrater reliability, as mentioned in Chapter 4. Researchers are expected to demonstrate the interrater reliability of their coding procedure by having multiple raters code the same behaviors independently and then showing that the different observers are in close agreement. Kraut and Johnston, for example, video recorded a subset of their participants’ reactions and had two observers independently code them. The two observers showed that they agreed on the reactions that were exhibited 97% of the time, indicating good interrater reliability.

One of the primary benefits of structured observation is that it is far more efficient than naturalistic and participant observation. Since the researchers are focused on specific behaviors this reduces time and expense. Also, often times the environment is structured to encourage the behaviors of interest which again means that researchers do not have to invest as much time in waiting for the behaviors of interest to naturally occur. Finally, researchers using this approach can clearly exert greater control over the environment. However, when researchers exert more control over the environment it may make the environment less natural which decreases external validity. It is less clear for instance whether structured observations made in a laboratory environment will generalize to a real world environment. Furthermore, since researchers engaged in structured observation are often not disguised there may be more concerns with reactivity.

Case Studies

A case study is an in-depth examination of an individual. Sometimes case studies are also completed on social units (e.g., a cult) and events (e.g., a natural disaster). Most commonly in psychology, however, case studies provide a detailed description and analysis of an individual. Often the individual has a rare or unusual condition or disorder or has damage to a specific region of the brain.

Like many observational research methods, case studies tend to be more qualitative in nature. Case study methods involve an in-depth, and often a longitudinal examination of an individual. Depending on the focus of the case study, individuals may or may not be observed in their natural setting. If the natural setting is not what is of interest, then the individual may be brought into a therapist’s office or a researcher’s lab for study. Also, the bulk of the case study report will focus on in-depth descriptions of the person rather than on statistical analyses. With that said some quantitative data may also be included in the write-up of a case study. For instance, an individual’s depression score may be compared to normative scores or their score before and after treatment may be compared. As with other qualitative methods, a variety of different methods and tools can be used to collect information on the case. For instance, interviews, naturalistic observation, structured observation, psychological testing (e.g., IQ test), and/or physiological measurements (e.g., brain scans) may be used to collect information on the individual.

HM is one of the most notorious case studies in psychology. HM suffered from intractable and very severe epilepsy. A surgeon localized HM’s epilepsy to his medial temporal lobe and in 1953 he removed large sections of his hippocampus in an attempt to stop the seizures. The treatment was a success, in that it resolved his epilepsy and his IQ and personality were unaffected. However, the doctors soon realized that HM exhibited a strange form of amnesia, called anterograde amnesia. HM was able to carry out a conversation and he could remember short strings of letters, digits, and words. Basically, his short term memory was preserved. However, HM could not commit new events to memory. He lost the ability to transfer information from his short-term memory to his long term memory, something memory researchers call consolidation. So while he could carry on a conversation with someone, he would completely forget the conversation after it ended. This was an extremely important case study for memory researchers because it suggested that there’s a dissociation between short-term memory and long-term memory, it suggested that these were two different abilities sub-served by different areas of the brain. It also suggested that the temporal lobes are particularly important for consolidating new information (i.e., for transferring information from short-term memory to long-term memory),

The history of psychology is filled with influential cases studies, such as Sigmund Freud’s description of “Anna O.” (see Note 6.1 “The Case of “Anna O.””) and John Watson and Rosalie Rayner’s description of Little Albert (Watson & Rayner, 1920) [7] , who allegedly learned to fear a white rat—along with other furry objects—when the researchers repeatedly made a loud noise every time the rat approached him.

The Case of “Anna O.”

Sigmund Freud used the case of a young woman he called “Anna O.” to illustrate many principles of his theory of psychoanalysis (Freud, 1961) [8] . (Her real name was Bertha Pappenheim, and she was an early feminist who went on to make important contributions to the field of social work.) Anna had come to Freud’s colleague Josef Breuer around 1880 with a variety of odd physical and psychological symptoms. One of them was that for several weeks she was unable to drink any fluids. According to Freud,

She would take up the glass of water that she longed for, but as soon as it touched her lips she would push it away like someone suffering from hydrophobia.…She lived only on fruit, such as melons, etc., so as to lessen her tormenting thirst. (p. 9)

But according to Freud, a breakthrough came one day while Anna was under hypnosis.

[S]he grumbled about her English “lady-companion,” whom she did not care for, and went on to describe, with every sign of disgust, how she had once gone into this lady’s room and how her little dog—horrid creature!—had drunk out of a glass there. The patient had said nothing, as she had wanted to be polite. After giving further energetic expression to the anger she had held back, she asked for something to drink, drank a large quantity of water without any difficulty, and awoke from her hypnosis with the glass at her lips; and thereupon the disturbance vanished, never to return. (p.9)

Freud’s interpretation was that Anna had repressed the memory of this incident along with the emotion that it triggered and that this was what had caused her inability to drink. Furthermore, he believed that her recollection of the incident, along with her expression of the emotion she had repressed, caused the symptom to go away.

As an illustration of Freud’s theory, the case study of Anna O. is quite effective. As evidence for the theory, however, it is essentially worthless. The description provides no way of knowing whether Anna had really repressed the memory of the dog drinking from the glass, whether this repression had caused her inability to drink, or whether recalling this “trauma” relieved the symptom. It is also unclear from this case study how typical or atypical Anna’s experience was.

Case studies are useful because they provide a level of detailed analysis not found in many other research methods and greater insights may be gained from this more detailed analysis. As a result of the case study, the researcher may gain a sharpened understanding of what might become important to look at more extensively in future more controlled research. Case studies are also often the only way to study rare conditions because it may be impossible to find a large enough sample of individuals with the condition to use quantitative methods. Although at first glance a case study of a rare individual might seem to tell us little about ourselves, they often do provide insights into normal behavior. The case of HM provided important insights into the role of the hippocampus in memory consolidation.

However, it is important to note that while case studies can provide insights into certain areas and variables to study, and can be useful in helping develop theories, they should never be used as evidence for theories. In other words, case studies can be used as inspiration to formulate theories and hypotheses, but those hypotheses and theories then need to be formally tested using more rigorous quantitative methods. The reason case studies shouldn’t be used to provide support for theories is that they suffer from problems with both internal and external validity. Case studies lack the proper controls that true experiments contain. As such, they suffer from problems with internal validity, so they cannot be used to determine causation. For instance, during HM’s surgery, the surgeon may have accidentally lesioned another area of HM’s brain (a possibility suggested by the dissection of HM’s brain following his death) and that lesion may have contributed to his inability to consolidate new information. The fact is, with case studies we cannot rule out these sorts of alternative explanations. So, as with all observational methods, case studies do not permit determination of causation. In addition, because case studies are often of a single individual, and typically an abnormal individual, researchers cannot generalize their conclusions to other individuals. Recall that with most research designs there is a trade-off between internal and external validity. With case studies, however, there are problems with both internal validity and external validity. So there are limits both to the ability to determine causation and to generalize the results. A final limitation of case studies is that ample opportunity exists for the theoretical biases of the researcher to color or bias the case description. Indeed, there have been accusations that the woman who studied HM destroyed a lot of her data that were not published and she has been called into question for destroying contradictory data that didn’t support her theory about how memories are consolidated. There is a fascinating New York Times article that describes some of the controversies that ensued after HM’s death and analysis of his brain that can be found at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/07/magazine/the-brain-that-couldnt-remember.html?_r=0

Archival Research

Another approach that is often considered observational research involves analyzing archival data that have already been collected for some other purpose. An example is a study by Brett Pelham and his colleagues on “implicit egotism”—the tendency for people to prefer people, places, and things that are similar to themselves (Pelham, Carvallo, & Jones, 2005) [9] . In one study, they examined Social Security records to show that women with the names Virginia, Georgia, Louise, and Florence were especially likely to have moved to the states of Virginia, Georgia, Louisiana, and Florida, respectively.

As with naturalistic observation, measurement can be more or less straightforward when working with archival data. For example, counting the number of people named Virginia who live in various states based on Social Security records is relatively straightforward. But consider a study by Christopher Peterson and his colleagues on the relationship between optimism and health using data that had been collected many years before for a study on adult development (Peterson, Seligman, & Vaillant, 1988) [10] . In the 1940s, healthy male college students had completed an open-ended questionnaire about difficult wartime experiences. In the late 1980s, Peterson and his colleagues reviewed the men’s questionnaire responses to obtain a measure of explanatory style—their habitual ways of explaining bad events that happen to them. More pessimistic people tend to blame themselves and expect long-term negative consequences that affect many aspects of their lives, while more optimistic people tend to blame outside forces and expect limited negative consequences. To obtain a measure of explanatory style for each participant, the researchers used a procedure in which all negative events mentioned in the questionnaire responses, and any causal explanations for them were identified and written on index cards. These were given to a separate group of raters who rated each explanation in terms of three separate dimensions of optimism-pessimism. These ratings were then averaged to produce an explanatory style score for each participant. The researchers then assessed the statistical relationship between the men’s explanatory style as undergraduate students and archival measures of their health at approximately 60 years of age. The primary result was that the more optimistic the men were as undergraduate students, the healthier they were as older men. Pearson’s r was +.25.

This method is an example of content analysis —a family of systematic approaches to measurement using complex archival data. Just as structured observation requires specifying the behaviors of interest and then noting them as they occur, content analysis requires specifying keywords, phrases, or ideas and then finding all occurrences of them in the data. These occurrences can then be counted, timed (e.g., the amount of time devoted to entertainment topics on the nightly news show), or analyzed in a variety of other ways.

- Festinger, L., Riecken, H., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails: A social and psychological study of a modern group that predicted the destruction of the world. University of Minnesota Press. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

- Wilkins, A. (2008). “Happier than Non-Christians”: Collective emotions and symbolic boundaries among evangelical Christians. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71 , 281–301. ↵

- Levine, R. V., & Norenzayan, A. (1999). The pace of life in 31 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30 , 178–205. ↵

- Kraut, R. E., & Johnston, R. E. (1979). Social and emotional messages of smiling: An ethological approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 , 1539–1553. ↵

- Cohen, D., Nisbett, R. E., Bowdle, B. F., & Schwarz, N. (1996). Insult, aggression, and the southern culture of honor: An "experimental ethnography." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 (5), 945-960. ↵

- Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3 , 1–14. ↵

- Freud, S. (1961). Five lectures on psycho-analysis . New York, NY: Norton. ↵

- Pelham, B. W., Carvallo, M., & Jones, J. T. (2005). Implicit egotism. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14 , 106–110. ↵

- Peterson, C., Seligman, M. E. P., & Vaillant, G. E. (1988). Pessimistic explanatory style is a risk factor for physical illness: A thirty-five year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55 , 23–27. ↵

Updated on 29 Oct, 2024

What is an observational study? Examples, types & definitions

Guides • Aakash Jethwani • 8 Mins reading time

When it comes to understanding human behavior and interactions, researchers often rely on methods that go beyond mere statistics. One such method is the observational study . But what is an observational study?

At its core, it involves watching and recording individuals in their natural environments without manipulating any variables. This approach allows researchers to gather rich, qualitative data about how people behave and interact in real-world settings.

Observational studies are widely used across fields like psychology , sociology , and market research to uncover insights that might be missed in controlled experiments.

In this design journal ’s blog, we will explore what is an observational study, the different types of observational studies, and how they can be effectively used to gain valuable insights into human behavior.

Observational study definition

An observational study is a research method where the researcher observes and records behavior, events, or phenomena without intervening or manipulating any variables.

The goal is to gather data on how things naturally occur in their usual setting, providing insights into real-world conditions. This type of study can be descriptive, focusing on detailing characteristics or behaviors, or analytical, investigating relationships between variables.

Observational studies are valuable for capturing data in a natural context, but they have limitations, including establishing cause-and-effect relationships and potential biases in data collection and interpretation.

Overall, they are useful for exploring phenomena and generating hypotheses for further research.

You may also like to read: What is a diary study?

Observational study examples

1. naturalistic observation.

In this type of observational study, researchers might observe wildlife in their natural habitats.

Let’s consider this observational study example: a biologist studying the social behaviors of elephants in the wild would document their interactions and movements without disturbing their environment.

This allows for a genuine understanding of the animals’ natural behaviors.

2. Participant observation

Here, researchers immerse themselves in the environment they are studying.

For instance, a sociologist might join a local community group to observe and participate in their activities.

This firsthand experience provides deeper insights into the group’s social dynamics and behaviors.