How to Write a Position Paper

In academia and the professional world, one of the most valuable writing skills to develop is the ability to clearly express and support a position in writing. When you write a position paper, this is the skill you’re strengthening.

Give your writing extra polish Grammarly helps you communicate confidently Write with Grammarly

What is a position paper?

A position paper is a type of academic writing that supports the author’s position on a topic through statistics, facts, and other pieces of well-researched, relevant evidence.

The purpose of a position paper is to clearly and concisely communicate the author’s position on a topic. For example, a teaching assistant may write a position paper about students’ use of AI writing tools in academic assignments. In this example, the author acknowledges how certain AI tools can enable students to work more efficiently while also acknowledging the tools’ drawbacks, such as other AI tools allowing students to avoid doing the actual writing. The author clearly states and supports their position with credible sources, and readers come away understanding the author’s exact position on the topic.

Position papers aren’t always individuals’ positions. They can also communicate groups’ and organizations’ positions on topics. To go back to our previous example, a university writing department may publish a paper on its official position regarding AI writing tools. This paper, which would be approximately one page long, would then become a go-to resource for students and faculty with questions about the department’s position on such tools. These are a few areas where position papers are frequently published and used this way:

- Government and organizational policy

How to write a position paper in 5 steps

1 choose a topic.

The first step in writing a position paper is choosing your topic. You may be assigned a topic, or you may need to develop a topic yourself. In either case, a good topic for a position paper is one that allows you to take a definable, defendable stance that you can back up with relevant data. This is why thoroughly researching your topic is critical to writing a strong position paper—which we’ll explore further in the next section.

2 Conduct research

Once you’ve determined your paper’s topic, the next step is to do a deep dive into it. At this stage, you may not have a clear position yet—that’s perfectly fine. You’ll determine your position by researching the subject.

Consult sources that support multiple positions on your topic. This way, you can find any logical fallacies , misunderstandings, and other shortcomings behind various positions one can take on the subject. Through your research, determine the most logical position to take in your paper. Remember, though, that a position paper isn’t based on opinions—although you’re taking the position that best reflects your understanding of the topic, you need to support that position with credible facts.

3 Write a thesis

Once you’ve determined the position you’ll take in your paper, write your thesis statement . Your paper’s thesis statement is the sentence that concisely states the position the rest of your paper will support.

4 Challenge your thesis

After you write a thesis statement, you need to challenge it. Arguing against your thesis statement in good faith demonstrates that you understand the topic from all angles and support your position from a place of logic and careful reasoning.

5 Collect supporting evidence

Including quotes from experts in your position paper can be beneficial, but be careful to avoid the appeal to authority fallacy . Their expertise must be directly relevant to your position, as do the quotes you include. An example of a relevant quote would be an excerpt from a pediatrician’s research on adolescent circadian rhythms in a position paper supporting later starting times for high schools. An irrelevant quote would be a parent’s anecdote that their teen often sleeps late and misses the bus. While this anecdote may be true, it’s not a researched or tested fact from an expert.

Position paper outline (with examples)

Introduction.

In the introduction, hook your reader with an engaging opening, then introduce your thesis statement. Then, briefly include your supporting argument.

Body paragraphs

The body paragraphs are where you support your thesis statement. You can include as many paragraphs as you need, but remember that a position paper is typically a short piece of writing . Include one body paragraph per argument—including counterarguments. In each counterargument paragraph, demonstrate the flaws in the counterargument using relevant, credible facts and figures.

Be careful to strike a balance between paragraphs supporting your position and paragraphs discrediting counterarguments. Overall, your paper should do more supporting than discrediting because the focus is your position’s strength, not its opposition’s weakness.

In the final section, restate your position and summarize your argument. You don’t need to restate your thesis statement word for word, but you should reinforce it here with a summary of the points you made in your paper’s body paragraphs.

Tips for writing a position paper

Identify your audience.

Before you begin to write, determine who will read your position paper. This will help you choose the right tone to use and which details and sources to include. A position paper meant to be read by others in your industry, for example, can use a more technical tone and include more jargon and industry-specific knowledge than a position paper you plan to publish for a wider audience.

Once you’ve determined your paper’s audience, figure out which sources make sense for that audience. If it’s an academic position paper, support your thesis statement with scholarly sources. If it’s a professional paper, support your thesis with industry-relevant statistics and insights from key leaders. And if you’re publishing your position paper as a blog post or opinion piece to be read by the general public, be sure to use sources that will resonate with them.

Include supporting research and data

Weave your sources into your paper. You can use direct quotes, paraphrasing, or both. Including credible sources, both in support of and against your position, demonstrates that you did your research and can back up any statement you make or refute others’ claims.

Choose a topic with two (or more) opposing sides

A strong position paper takes a clear position on a topic that people can disagree about. When there’s no disagreement about a topic, it’s difficult to write a compelling position paper.

For example, a position paper about why humans need to drink water wouldn’t be very compelling. You’d be hard-pressed to find someone who disagrees with your position that everyone needs to drink water every day. A better topic for a position paper would be whether it’s more harmful or beneficial for people to drink coffee every day because there is detailed research to support both positions.

Cite your sources

It’s not enough to include references; you need to cite your sources as well. In most cases, you’re required to include a bibliography that lists the sources you used to research your position paper. Even when this isn’t a requirement, citations show that you have credible sources to support your position.

As with any other type of writing, proofread your position paper before you send it to your professor, colleagues, or supervisor, or before you publish it on your LinkedIn profile or website. A spelling or grammatical mistake can undermine your position—and it takes only a second to fix.

Position paper vs. argumentative essay

A position paper states a position and supports it through references to credible sources. An argumentative essay is similar, but it generally presents its position as an argument or question rather than as a statement. Here are a few examples of titles for both:

Position paper: A Car-Free Campus Is Healthier for Everyone

Argumentative essay: Should Cars Be Banned From Campus?

Position paper: Legacy Status Is an Outdated Metric

Argumentative essay: Is It Time to Stop Considering Legacy Status?

In many ways, a position paper is similar to an argumentative essay , with the key difference being their goals. An argumentative essay’s goal is to sway the reader’s opinion on its topic by guiding them through a nuanced, balanced look at various positions, leading them to the position the author supports. A position paper is a shorter piece of writing that spends less time exploring opposing positions and instead simply presents the reasons the author holds their position.

Position paper FAQs

A position paper is a type of academic writing that supports an author’s or organization’s position on a topic through statistics, facts, and other pieces of well-researched, relevant evidence.

Which professions publish position papers?

Professional areas that use position papers include legal, research, healthcare, government, and organizational policy.

What’s the difference between a position paper and an argumentative essay?

A position paper states a position and supports it through evidence from credible sources. An argumentative essay has a broader scope and generally presents its position as a reasoned argument or question rather than as an evidence-driven position.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Position Paper – Example, Format and Writing Guide

Position Paper – Example, Format and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

A position paper is a critical document that outlines an individual’s or organization’s stance on a particular issue or topic. It provides a well-reasoned argument supported by evidence, aiming to persuade readers to adopt a specific viewpoint. Whether for academic purposes, policy advocacy, or professional discussions, a well-crafted position paper demonstrates analytical thinking and effective communication. This article explores the format, provides an example, and offers a step-by-step guide for writing a compelling position paper.

Position Paper

A position paper is a formal essay that presents a detailed argument on a specific issue, articulating the author’s position and backing it with evidence, research, and logical reasoning. Its primary goal is to clarify the stance and convince the audience of its validity.

For example, a student may write a position paper arguing for the benefits of renewable energy policies, supporting the stance with data on environmental impact, economic advantages, and technological advancements.

Purpose of a Position Paper

- Clarify Position : Helps articulate a clear and concise stance on an issue.

- Persuade Audience : Aims to convince readers by presenting compelling arguments and evidence.

- Promote Dialogue : Encourages constructive discussion and critical thinking about the topic.

- Demonstrate Knowledge : Shows the author’s depth of understanding and ability to analyze complex issues.

Format of a Position Paper

A position paper typically follows a standard format to ensure clarity and logical flow. Below is the general structure:

- A concise and descriptive title that reflects the issue and stance.

- Example : “The Case for Renewable Energy: Addressing Climate Change Through Sustainable Solutions.”

2. Introduction

- Briefly introduce the topic and its relevance.

- Clearly state your position or thesis statement.

- Provide context or background information on the issue.

- Example : “With climate change posing a significant threat to global ecosystems, transitioning to renewable energy is imperative. This paper argues that renewable energy policies are essential for mitigating environmental degradation and fostering sustainable economic growth.”

3. Arguments Supporting Your Position

- Present 2–3 strong arguments that justify your stance.

- Back each argument with credible evidence, such as data, research studies, or expert opinions.

- Use logical reasoning to connect evidence with your claims.

- Evidence : Studies show solar and wind energy can reduce CO2 emissions by up to 80% compared to fossil fuels.

- Evidence : Job creation in renewable energy industries outpaces traditional energy sectors.

4. Counterarguments and Rebuttals

- Address potential opposing viewpoints or criticisms.

- Provide reasoned rebuttals to demonstrate why your position remains valid.

- Example : “Critics argue that renewable energy is costly. However, recent advancements in solar panel technology have significantly reduced costs, making renewables more affordable than fossil fuels in many regions.”

5. Conclusion

- Summarize the key points made in the paper.

- Reinforce the importance of your position and its implications.

- Include a call to action or suggest further research.

- Example : “Embracing renewable energy is not just a necessity but a responsibility. Governments and organizations must prioritize policies that accelerate this transition for a sustainable future.”

6. References

- Provide a list of sources cited in your paper to enhance credibility.

- Follow the required citation style (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago).

Example of a Position Paper

“Reducing Plastic Waste: A Call for Global Action”

Introduction :

Plastic pollution has reached alarming levels, threatening marine ecosystems and public health. With over 8 million tons of plastic entering the oceans annually, immediate action is necessary to address this crisis. This paper argues that implementing strict regulations on plastic production and promoting biodegradable alternatives are essential for mitigating the impacts of plastic waste.

Arguments Supporting the Position :

- Environmental Impact : Plastic waste harms marine life and ecosystems. Studies indicate that over 1 million marine animals die annually due to plastic ingestion or entanglement. Regulating plastic production can reduce this catastrophic impact.

- Health Concerns : Microplastics have been detected in food, water, and air, posing health risks to humans. Policies reducing plastic use will decrease exposure to these harmful particles.

- Economic Benefits of Alternatives : Promoting biodegradable materials can stimulate new industries and create green jobs. For example, a study by the Environmental Policy Institute highlights that transitioning to biodegradable packaging could generate over 100,000 jobs globally.

Counterarguments and Rebuttals :

- Counterargument : Plastic is cheap and versatile, making it difficult to replace.

- Rebuttal : While plastic is inexpensive, its environmental and health costs far outweigh its short-term economic benefits. Investments in research and subsidies for biodegradable alternatives can address affordability concerns.

Conclusion :

Reducing plastic waste requires a collaborative effort between governments, industries, and individuals. By implementing stricter regulations and fostering innovation, we can protect ecosystems, improve public health, and create sustainable economic opportunities. The time to act is now.

References :

- Jambeck, J. R., et al. (2015). “Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean.” Science , 347(6223), 768–771.

- World Economic Forum. (2020). The New Plastics Economy .

- Environmental Policy Institute. (2021). “Economic Opportunities in Biodegradable Packaging.”

Step-by-Step Writing Guide

Step 1: choose a relevant topic.

Select a topic that aligns with your interests and is significant to your audience. Ensure the topic allows for a clear position to be taken.

- Example Topics :

- “Should Social Media Be Regulated to Prevent Misinformation?”

- “The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Education.”

Step 2: Research Thoroughly

Gather credible evidence to support your position. Use academic articles, books, reputable websites, and expert opinions to build a strong foundation.

Step 3: Outline Your Paper

Organize your arguments, counterarguments, and supporting evidence into a logical structure. Use the format provided earlier to create a clear outline.

Step 4: Write the Draft

Start with a compelling introduction that captures the reader’s attention and clearly states your position. Develop each section systematically, ensuring smooth transitions between paragraphs.

Step 5: Revise and Edit

Review your paper for clarity, coherence, and accuracy. Eliminate redundant arguments, strengthen weak points, and proofread for grammar and formatting errors.

Step 6: Cite Your Sources

Provide proper citations for all sources used to enhance credibility and avoid plagiarism.

Tips for Writing an Effective Position Paper

- Be Clear and Concise : Avoid vague statements and focus on presenting a clear position.

- Use Credible Evidence : Support your arguments with reliable and well-documented evidence.

- Address Counterarguments : Acknowledge opposing views to demonstrate thorough understanding.

- Maintain a Formal Tone : Use professional language and avoid overly emotional appeals.

- Stay Focused : Stick to the main topic and avoid deviating into unrelated issues.

A position paper is a powerful tool for presenting well-reasoned arguments and influencing discussions on critical issues. By following the format, leveraging credible evidence, and addressing counterarguments, writers can craft compelling papers that effectively communicate their stance. Whether in academia, policymaking, or professional settings, mastering the art of position paper writing is invaluable for making an impact.

- Corey, S. (2020). Writing Effective Position Papers: A Practical Guide for Researchers and Advocates . Sage Publications.

- Purdue Online Writing Lab. (2023). “Position Paper Resources.”

- Babbie, E. (2021). The Practice of Social Research (15th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . Sage Publications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Predictive Analytics in Cyber Security –...

Scholarly Paper – Format, Example and Writing...

Artist – Definition,Types and Work Area

Theory – Definition, Types and Examples

Biologist – Definition, Types and Work Area

What is Science – Definition, Methods, Types

10.5 Writing Process: Creating a Position Argument

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Demonstrate brainstorming processes and tools as means to discover topics, ideas, positions, and details.

- Apply recursive strategies for organizing drafting, collaborating, peer reviewing, revising, rewriting, and editing.

- Compose a position argument that integrates the writer’s ideas with those from appropriate sources.

- Give and act on productive feedback to works in progress.

- Apply or challenge common conventions of language or grammar in composing and revising.

Now is the time to try your hand at writing a position argument. Your instructor may provide some possible topics or a singular topic. If your instructor allows you to choose your own topic, consider a general subject you feel strongly about and whether you can provide enough support to develop that subject into an essay. For instance, suppose you think about a general subject such as “adulting.” In looking back at what you have learned while becoming an adult, you think of what you wish you had known during your early teenage years. These thoughts might lead you to brainstorm about details of the effects of money in your life or your friends’ lives. In reviewing your brainstorming, you might zero in on one topic you feel strongly about and think it provides enough depth to develop into a position argument. Suppose your brainstorming leads you to think about negative financial concerns you or some of your friends have encountered. Thinking about what could have helped address those concerns, you decide that a mandated high school course in financial literacy would have been useful. This idea might lead you to formulate your working thesis statement —first draft of your thesis statement—like this: To help students learn how to make sensible financial decisions, a mandatory class in financial literacy should be offered in high schools throughout the country.

Once you decide on a topic and begin moving through the writing process, you may need to fine-tune or even change the topic and rework your initial idea. This fine-tuning may come as you brainstorm, later when you begin drafting, or after you have completed a draft and submitted it to your peers for constructive criticism. These possibilities occur because the writing process is recursive —that is, it moves back and forth almost simultaneously and maybe even haphazardly at times, from planning to revising to editing to drafting, back to planning, and so on.

Summary of Assignment

Write a position argument on a controversial issue that you choose or that your instructor assigns to you. If you are free to choose your own topic, consider one of the following:

- The legal system would be strengthened if ______________________.

- The growing use of technology in college classrooms is weakening _____________.

- For safety reasons, public signage should be _________________.

- For entrance into college, standardized testing _________________________.

- In relation to the cost of living, the current minimum wage _______________________.

- During a pandemic, America __________________________.

- As a requirement to graduate, college students __________________________.

- To guarantee truthfulness of their content, social media platforms have the right to _________________.

- To ensure inclusive and diverse representation of people of all races, learning via virtual classrooms _________________.

- Segments of American cultures have differing rules of acceptable grammar, so in a college classroom ___________________.

In addition, if you have the opportunity to choose your own topic and wish to search further, take the lead from trailblazer Charles Blow and look to media for newsworthy “trends.” Find a controversial issue that affects you or people you know, and take a position on it. As you craft your argument, identify a position opposing yours, and then refute it with reasoning and evidence. Be sure to gather information on the issue so that you can support your position sensibly with well-developed ideas and evidence.

Another Lens. To gain a different perspective on your issue, consider again the people affected by it. Your position probably affects different people in different ways. For example, if you are writing that the minimum wage should be raised, then you might easily view the issue through the lens of minimum-wage workers, especially those who struggle to make ends meet. However, if you look at the issue through the lens of those who employ minimum-wage workers, your viewpoint might change. Depending on your topic and thesis, you may need to use print or online sources to gain insight into different perspectives.

For additional information about minimum-wage workers, you could consult

- printed material available in your college library;

- databases in your college library; and

- pros and cons of raising the minimum wage;

- what happens after the minimum wage is raised;

- how to live on a minimum-wage salary;

- how a raise in minimum wage is funded; and

- minimum wage in various U.S. states.

To gain more insight about your topic, adopt a stance that opposes your original position and brainstorm ideas from that viewpoint. Begin by gathering evidence that would help you refute your previous stance and appeal to your audience.

Quick Launch: Working Thesis Frames and Organization of Ideas

After you have decided on your topic, the next step is to arrive at your working thesis. You probably have a good idea of the direction your working thesis will take. That is, you know where you stand on the issue or problem, but you are not quite sure of how to word your stance to share it with readers. At this point, then, use brainstorming to think critically about your position and to discover the best way to phrase your statement.

For example, after reading an article discussing different state-funded community college programs, one student thought that a similar program was needed in Alabama, her state. However, she was not sure how the program worked. To begin, she composed and answered “ reporters’ questions ” such as these:

- What does a state-funded community college program do? pays for part or all of the tuition of a two-year college student

- Who qualifies for the program? high school graduates and GED holders

- Who benefits from this? students needing financial assistance, employers, and Alabama residents

- Why is this needed? some can’t afford to go to college; tuition goes up every year; colleges would be more diverse if everyone who wanted to go could afford to go

- Where would the program be available? at all public community colleges

- When could someone apply for the program? any time

- How can the state fund this ? use lottery income, like other states

The student then reviewed her responses, altered her original idea to include funding through a lottery, and composed this working thesis:

student sample text To provide equal educational opportunities for all residents, the state of Alabama should create a lottery to completely fund tuition at community colleges. end student sample text

Remember that a strong thesis for a position should

- state your stance on a debatable issue;

- reflect your purpose of persuasion; and

- be based on your opinion or observation.

When you first consider your topic for an argumentative work, think about the reasoning for your position and the evidence you will need—that is, think about the “because” part of your argument. For instance, if you want to argue that your college should provide free Wi-Fi for every student, extend your stance to include “because” and then develop your reasoning and evidence. In that case, your argument might read like this: Ervin Community College should provide free Wi-Fi for all students because students may not have Internet access at home.

Note that the “because” part of your argument may come at the beginning or the end and may be implied in your wording.

As you develop your thesis, you may need help funneling all of your ideas. Return to the possibilities you have in mind, and select the ideas that you think are strongest, that recur most often, or that you have the most to say about. Then use those ideas to fill in one of the following sentence frames to develop your working thesis. Feel free to alter the frame as necessary to fit your position. While there is no limit to the frames that are possible, these may help get you started.

________________ is caused/is not caused by ________________, and _____________ should be done.

Example: A declining enrollment rate in college is caused by high tuition rates, and an immediate freeze on the cost of tuition should be applied.

______________ should/should not be allowed (to) ________________ for a number of reasons.

Example: People who do not wear masks during a pandemic should not be allowed to enter public buildings for a number of reasons.

Because (of) ________________, ___________________ will happen/continue to happen.

Example: Because of a lack of emphasis on STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts, and Mathematics) education in public schools, America will continue to lag behind many other countries.

_____________ is similar to/nothing like ________________ because ______________.

Example: College classes are nothing like high school classes because in college, more responsibility is on the student, the classes are less frequent but more intense, and the work outside class takes more time to complete.

______________ can be/cannot be thought of as __________________ because ______________.

Example: The Black Lives Matter movement can be thought of as an extension of the Civil Rights movement from the 1950s and 1960s because it shares the same mission of fighting racism and ending violence against Black people.

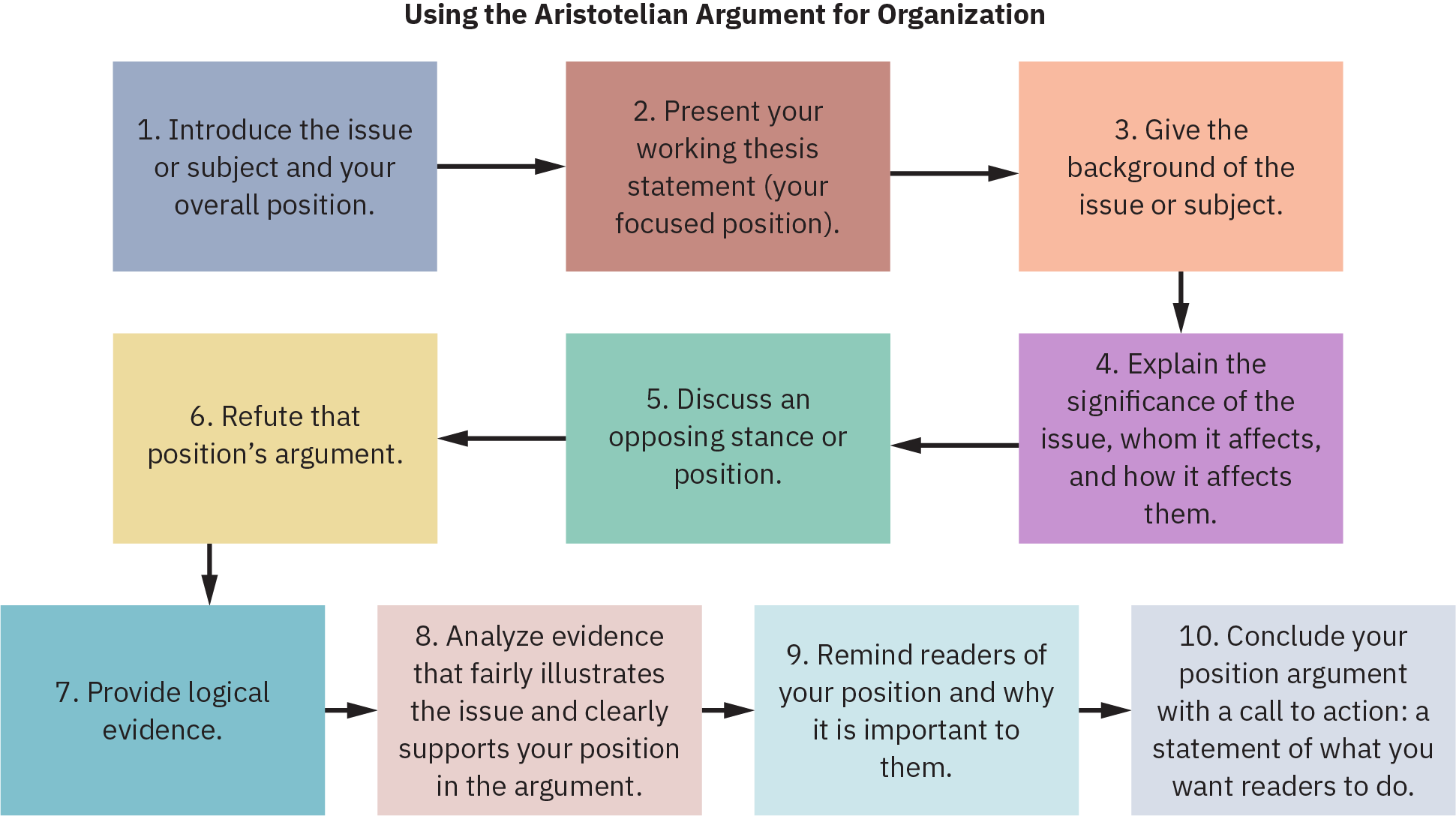

Next, consider the details you will need to support your thesis. The Aristotelian argument structure, named for the Greek philosopher Aristotle , is one that may help you frame the draft of your position argument. For this method, use something like the following chart. In Writing Process: Creating a Position Argument, you will find a similar organizer that you can copy and use for your assignment.

Drafting: Rhetorical Appeals and Types of Supporting Evidence

To persuade your audience to support your position or argument, consider various rhetorical appeals— ethos, logos, pathos, and kairos—and the types of evidence to support your sound reasoning. See Reasoning Strategies: Improving Critical Thinking for more information on reasoning strategies and types of evidence.

Rhetorical Appeals

To establish your credibility, to show readers you are trustworthy, to win over their hearts, and to set your issue in an appropriate time frame to influence readers, consider how you present and discuss your evidence throughout the paper.

- Appeal to ethos . To establish credibility in her paper arguing for expanded mental health services, a student writer used these reliable sources: a student survey on mental health issues, data from the International Association of Counseling Services (a professional organization), and information from an interview with a campus mental health counselor.

- Appeal to logos . To support her sound reasoning, the student writer approached the issue rationally, using data and credible evidence to explain the current situation and its effects.

- Appeal to pathos . To show compassion and arouse audience empathy, the student writer shared the experience of a student on her campus who struggled with anxiety and depression.

- Appeal to kairos . To appeal to kairos, the student emphasized the immediate need for these services, as more students are now aware of their particular mental health issues and trying to deal with them.

The way in which you present and discuss your evidence will reflect the appeals you use. Consider using sentence frames to reflect specific appeals. Remember, too, that sentence frames can be composed in countless ways. Here are a few frames to get you thinking critically about how to phrase your ideas while considering different types of appeals.

Appeal to ethos: According to __________________, an expert in ______________, __________________ should/should not happen because ________________________.

Appeal to ethos: Although ___________________is not an ideal situation for _________________, it does have its benefits.

Appeal to logos: If ____________________ is/is not done, then understandably, _________________ will happen.

Appeal to logos: This information suggests that ____________________ needs to be investigated further because ____________________________.

Appeal to pathos: The story of _____________________ is uplifting/heartbreaking/hopeful/tragic and illustrates the need for ____________________.

Appeal to pathos: ___________________ is/are suffering from ________________, and that is something no one wants.

Appeal to kairos: _________________ must be addressed now because ________________ .

Appeal to kairos: These are times when ______________ ; therefore, _____________ is appropriate/necessary.

Types of Supporting Evidence

Depending on the point you are making to support your position or argument, certain types of evidence may be more effective than others. Also, your instructor may require you to include a certain type of evidence. Choose the evidence that will be most effective to support the reasoning behind each point you make to support your thesis statement. Common types of evidence are these:

Renada G., a junior at Powell College South, worked as a waitress for 15 hours a week during her first three semesters of college. But in her sophomore year, when her parents were laid off during the pandemic, Renada had to increase her hours to 35 per week and sell her car to stay in school. Her grades started slipping, and she began experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety. When she called the campus health center to make an appointment for counseling, Renada was told she would have to wait two weeks before she could be seen.

Here is part of how Lyndon B. Johnson defined the Great Society: “But most of all, the Great Society is not a safe harbor, a resting place, a final objective, a finished work. It is a challenge constantly renewed, beckoning us toward a destiny where the meaning of our lives matches the marvelous products of our labor.”

Bowen Lake is nestled in verdant foothills, lush with tall grasses speckled with wildflowers. Around the lake, the sweet scent of the purple and yellow flowers fills the air, and the fragrance of the hearty pines sweeps down the hillsides in a westerly breeze. Wood frogs’ and crickets’ songs suddenly stop, as the blowing of moose calling their calves echoes across the lake’s soundless surface. Or this was the scene before the deadly destruction of fires caused by climate change.

When elaborating on America’s beauty being in danger, Johnson says, “The water we drink, the food we eat, the very air that we breathe, are threatened with pollution. Our parks are overcrowded, our seashores overburdened. Green fields and dense forests are disappearing.”

Speaking about President Lyndon B. Johnson and the Vietnam War, noted historian and Johnson biographer Doris Kearns Goodwin said, “It seemed the hole in his heart from the loss of work was too big to fill.”

Charles Blow has worked at the Shreveport Times , The Detroit News , National Geographic , and The New York Times .

When interviewed by George Rorick and asked about the identities of his readers, Charles Blow said that readers’ emails do not elaborate on descriptions of who the people are. However, “the kinds of comments that they offer are very much on the thesis of the essay.”

In his speech, Lyndon B. Johnson says, “The Great Society is a place where every child can find knowledge to enrich his mind and to enlarge his talents.”

To support the need for change in classrooms, Johnson uses these statistics: “Each year more than 100,000 high school graduates, with proved ability, do not enter college because they cannot afford it. And if we cannot educate today’s youth, what will we do in 1970 when elementary school enrollment will be five million greater than 1960?”

- Visuals : graphs, photographs, charts, or maps used in addition to written or spoken information.

Brainstorm for Supporting Points

Use one or more brainstorming techniques, such as a web diagram as shown in Figure 10.8 or the details generated from “because” statements, to develop ideas or particular points in support of your thesis. Your goal is to get as many ideas as possible. At this time, do not be concerned about how ideas flow, whether you will ultimately use an idea (you want more ideas than will end up in your finished paper), spelling, or punctuation.

When you have finished, look over your brainstorming. Then circle three to five points to incorporate into your draft. Also, plan to answer “ reporters’ questions ” to provide readers with any needed background information. For example, the student writing about the need for more mental health counselors on her campus created and answered these questions:

What is needed? More mental health counseling is needed for Powell College South.

Who would benefit from this? The students and faculty would benefit.

- Why is this needed? The college does not have enough counselors to meet all students’ needs.

- Where are more counselors needed? More counselors are needed at the south campus.

- When are the counselors needed? Counselors need to be hired now and be available both day and night to accommodate students’ schedules.

- How can the college afford this ? Instead of hiring daycare workers, the college could use students and faculty from the Early Childhood Education program to run the program and use the extra money to pay the counselors.

Using Logic

In a position argument, the appropriate use of logic is especially important for readers to trust what you write. It is also important to look for logic in material you read and possibly cite in your paper so that you can determine whether writers’ claims are reasonable. Two main categories of logical thought are inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning .

- Inductive reasoning moves from specific to broad ideas. You begin by collecting details, observations, incidents, or facts; examining them; and drawing a conclusion from them. Suppose, for example, you are writing about attendance in college classes. For three weeks, you note the attendance numbers in all your Monday, Wednesday, and Friday classes (specific details), and you note that attendance is lower on Friday than on the other days (a specific detail). From these observations, you determine that many students prefer not to attend classes on Fridays (your conclusion).

- Deductive reasoning moves from general to specific ideas. You begin with a hypothesis or premise , a general concept, and then examine possibilities that would lead to a specific and logical conclusion. For instance, suppose you think that opportunities for foreign students at your college are inadequate (general concept). You examine the specific parts of that concept (e.g., whether your college provides multicultural clubs, help with language skills, or work-study opportunities) and determine that those opportunities are not available. You then determine that opportunities for foreign students are lacking at your college.

Logical Fallacies and Propaganda

Fallacies are mistakes in logic. Readers and writers should be aware of these when they creep into writing, indicating that the points the writers make may not be valid. Two common fallacies are hasty generalizations and circular arguments. See Glance at Genre: Rhetorical Strategies for more on logical fallacies.

- A hasty generalization is a conclusion based on either inadequate or biased evidence. Consider this statement: “Two students in Math 103 were nervous before their recent test; therefore, all students in that class must have text anxiety.” This is a hasty generalization because the second part of the statement (the generalization about all students in the class) is inadequate to support what the writer noted about only two students.

- A circular argument is one that merely restates what has already been said. Consider this statement: “ The Hate U Give is a well-written book because Angie Thomas, its author, is a good novelist.” The statement that Thomas is a good novelist does not explain why her book is well written.

In addition to checking work for fallacies, consider propaganda , information worded so that it endorses a particular viewpoint, often of a political nature. Two common types of propaganda are bandwagon and fear .

- In getting on the bandwagon , the writer encourages readers to conform to a popular trend and endorse an opinion, a movement, or a person because everyone else is doing so. Consider this statement: “Everyone is behind the idea that 7 a.m. classes are too early and should be changed to at least 8 a.m. Shouldn’t you endorse this sensible idea, too?”

- In using fear, the writer presents a dire situation, usually followed by what could be done to prevent it. Consider this statement: “Our country is at a turning point. Enemies threaten us with their power, and our democracy is at risk of being crushed. The government needs a change, and Paul Windhaus is just the man to see we get that change.” This quotation appeals to fear about the future of the country and implies that electing a certain individual will solve the predicted problems.

Organize the Paper

To begin, write your thesis at the top of a blank page. Then select points from your brainstorming and reporters’ questions to organize and develop support for your thesis. Keep in mind that you can revise your thesis whenever needed.

To begin organizing her paper on increased mental health services on her college campus, the student wrote this thesis at the top of a page:

student sample text Because mental health is a major concern at Powell College South, students could benefit from expanding the services offered . end student sample text

Next she decided the sequence in which to present the points. In a position or an argument essay, she could choose one of two methods: thesis-first organization or delayed-thesis organization.

Thesis-First Organization

Leading with a thesis tells readers from the beginning where you stand on the issue. In this organization, the thesis occupies both the first and last position in the essay, making it easy for readers to remember.

Introduce the issue and assert your thesis. Make sure the issue has at least two debatable sides. Your thesis establishes the position from which you will argue. Writers often state their thesis as the last sentence in the first paragraph, as the student writer has done:

student sample text The problem of mental health has become front-page news in the last two months. Hill’s Herald , Powell College South’s newspaper, reported 14 separate incidents of students who sought counseling but could not get appointments with college staff. Since mental health problems are widespread among the student population, the college should hire more health care workers to address this problem. end student sample text

Summarize the counterclaims . Before elaborating on your claims, explain the opposition’s claims. Including this information at the beginning gives your argument something to focus on—and refute—throughout the paper. If you ignore counterclaims, your argument may appear incomplete, and readers may think you have not researched your topic sufficiently. When addressing a counterclaim, state it clearly, show empathy for those who have that view, and then immediately refute it with support developed through reasoning and evidence. Squeezing the counterclaims between the thesis and the evidence reserves the strongest places—the opening and closing—for your position.

student sample text Counterclaim 1 : Powell College South already employs two counselors, and that number is sufficient to meet the needs of the student population. end student sample text

student sample text Counterclaim 2 : Students at Powell College South live in a metropolitan area large enough to handle their mental health needs. end student sample text

Refute the counterclaims. Look for weak spots in the opposition’s argument, and point them out. Use your opponent’s language to show you have read closely but still find problems with the claim. This is the way the writer refuted the first counterclaim:

student sample text While Powell College South does employ two counselors, those counselors are overworked and often have no time slots available for students who wish to make appointments. end student sample text

State and explain your points, and then support them with evidence. Present your points clearly and precisely, using Reasoning Strategies: Improving Critical Thinking to explain and cite your evidence. The writer plans to use a problem-solution reasoning strategy to elaborate on these three points using these pieces of evidence:

student sample text Point 1: Wait times are too long. end student sample text

student sample text Kay Payne, one of the campus counselors, states that the wait time for an appointment with her is approximately 10 days. end student sample text

student sample text Point 2: Mental health issues are widespread within the student community. end student sample text

student sample text In a recent on-campus student survey, 75 percent of 250 students say they have had some kind of mental health issues at some point in their life. end student sample text

student sample text Point 3: The staff-to-student ratio is too high. end student sample text

student sample text The International Accreditation of Counseling Services states that the recommended ratio is one full-time equivalent staff member for every 1,000 to 1,500 students. end student sample text

Restate your position as a conclusion. Near the end of your paper, synthesize your accumulated evidence into a broad general position, and restate your thesis in slightly different language.

student sample text The number of students who need mental health counseling is alarming. The recent news articles that attest to their not being able to schedule appointments add to the alarm. While Powell College South offers some mental health counseling, the current number of counselors and others who provide health care is insufficient to handle the well-being of all its students. Action must be taken to address this problem. end student sample text

Delayed-Thesis Organization

In this organizational pattern, introduce the issue and discuss the arguments for and against it, but wait to take a side until late in the essay. By delaying the stance, you show readers you are weighing the evidence, and you arouse their curiosity about your position. Near the end of the paper, you explain that after carefully considering both pros and cons, you have arrived at the most reasonable position.

Introduce the issue. Here, the writer begins with action that sets the scene of the problem.

student sample text Tapping her foot nervously, Serena looked at her watch again. She had been waiting three hours to see a mental health counselor at Powell College South, and she did not think she could wait much longer. She had to get to work. end student sample text

Summarize the claims for one position. Before stating which side you support, explain how the opposition views the issue. This body paragraph presents evidence about the topic of more counselors:

student sample text Powell College South has two mental health counselors on staff. If the college hires more counselors, more office space will have to be created. Currently Pennington Hall could accommodate those counselors. Additional counselors would allow more students to receive counseling. end student sample text

Refute the claims you just stated. Still not stating your position, point out the other side of the issue.

student sample text While office space is available in Pennington Hall, that location is far from ideal. It is in a wooded area of campus, six blocks from the nearest dorm. Students who would go there might be afraid to walk through the woods or might be afraid to walk that distance. The location might deter them from making appointments. end student sample text

Now give the best reasoning and evidence to support your position. Because this is a delayed-thesis organization, readers are still unsure of your stance. This section should be the longest and most carefully documented part of the paper. After summarizing and refuting claims, the writer then elaborates on these three points using problem-solution reasoning supported by this evidence as discussed in Reasoning Strategies: Improving Critical Thinking, implying her position before moving to the conclusion, where she states her thesis.

student sample text The International Association of Counseling Services states that one full-time equivalent staff member for every 1,000 to 1,500 students is the recommended ratio. end student sample text

State your thesis in your conclusion. Your rhetorical strategy is this: after giving each side a fair hearing, you have arrived at the most reasonable conclusion.

student sample text According to the American Psychological Association, more than 40 percent of all college students suffer from some form of anxiety. Powell College South students are no different from college students elsewhere: they deserve to have adequate mental health counseling. end student sample text

Drafting begins when you organize your evidence or research notes and then put them into some kind of written form. As you write, focus on building body paragraphs through the techniques presented in Reasoning Strategies: Improving Critical Thinking that show you how to support your position and then add evidence. Using a variety of evidence types builds credibility with readers. Remember that the recursiveness of the writing process allows you to move from composing to gathering evidence and back to brainstorming ideas or to organizing your draft at any time. Move around the writing process as needed.

Keep in mind that a first draft is just a beginning—you will revise it into a better work in later drafts. Your first draft is sometimes called a discovery draft because you are discovering how to shape your paper: which ideas to include and how to support those ideas. These suggestions and graphic organizer may be helpful for your first draft:

- Write your thesis at the top of the paper.

- Compose your body paragraphs: those that support your argument through reasoning strategies and those that address counterclaims.

- Leave your introduction, conclusion, and title for later drafts.

Use a graphic organizer like Table 10.1 to focus points, reasoning, and evidence for body paragraphs. You are free to reword your thesis, reasoning, counterclaim(s), refutation of counterclaim(s), concrete evidence, and explanation/elaboration/clarification at any time. You are also free to adjust the order in which you present your reasoning, counterclaim(s), and refuting of counterclaim(s).

Develop a Writing Project through Multiple Drafts

Your first draft is a kind of experiment in which you are concerned with ideas and with getting the direction and concept of the paper clear. Do not think that your first draft must be perfect; remind yourself that you are just honing your work. In most serious writing, every phase of the process can be considered recursive, helping you shape the best paper possible.

Peer Review: Critical Thinking and Counterclaims

After you have completed the first draft, begin peer review. Peer reviewers can use these sentence starters when thinking critically about overall strengths and developmental needs.

- One point about your position that I think is strong is ______ because ________.

- One point about your position that I think needs more development is _____ because _______.

- One area that I find confusing is _____________; I was confused about _______.

- One major point that I think needs more explanation or detail is _______.

- In my opinion, the purpose of your paper is to persuade readers _______.

- In my opinion, the audience for your paper is _______.

- One area of supporting evidence that I think could use more development is _______.

- One counterclaim you include is ________________.

- Your development of the counterclaim is __________________ because ________________.

Refuting Counterclaims

Peer reviewers are especially helpful with position and argument writing when it comes to refuting counterclaims. Have your peer reviewer read your paper again and look for supporting points and ideas to argue against , trying to break down your argument. Then ask your reviewer to discuss the counterclaims and corresponding points or ideas in your paper. This review will give you the opportunity to think critically about ways to refute the counterclaims your peer reviewer suggests.

As preparation for peer review, match each of the following arguments with their counterarguments.

Revising: Reviewing a Draft and Responding to Counterclaims

Revising means reseeing, rereading, and rethinking your thoughts on paper until they fully match your intention. Mentally, it is conceptual work focused on units of meaning larger than the sentence. Physically, it is cutting, pasting, deleting, and rewriting until the ideas are satisfying. Be ready to spend a great deal of time revising your drafts, adding new information and incorporating sources smoothly into your prose.

The Revising Process

To begin revising, return to the basic questions of topic ( What am I writing about? ), purpose ( Why am I writing about this topic? ), audience ( For whom am I writing? ), and culture ( What is the background of the people for whom I am writing? ).

- What is the general scope of my topic? __________________________________

- What is my thesis? __________________________________________________

- Does my thesis focus on my topic? ______________________________________

- Does my thesis clearly state my position? ______________________

- What do I hope to accomplish in writing about this topic? ____________________

- Do all parts of the paper advance this purpose? ____________________________

- Does my paper focus on my argument or position? _________________________

- What does my audience know about this subject? _______________________

- What does my audience need to know to understand the point of my paper? _______________________________________________________________

What questions or objections do I anticipate from my audience? ___________

________________________________________________________________

- What is the culture of the people for whom I am writing? Do all readers share the same culture? ________________________________________________________

How do my beliefs, values, and customs differ from those of my audience?

____________________________________________________________________

- How do the cultures of the authors of sources I cite differ from my culture or the culture(s) of my audience? ______________________________________________

Because of the recursivity of the writing process, returning to these questions will help you fine-tune the language and structure of your writing and target the support you develop for your audience.

Responding to Counterclaims

The more complex the issue, the more opposing sides it may have. For example, a writer whose position is that Powell College South Campus should offer daycare to its students with children might find opposition for different reasons. Someone may oppose the idea out of concern for cost; someone else may support the idea if the daycare is run on a volunteer basis; someone else may support the idea if the services are offered off campus.

As you revise, continue studying your peer reviewer’s comments about counterclaims. If you agree with any counterclaim, then say so in the paragraph in which you address counterclaims. This agreement will further establish your credibility by showing your fairness and concern for the issue. Look over your paper and peer review comments, and then consider these questions:

- In what ways do you address realistic counterclaims? What other counterclaims should you address? Should you add to or replace current counterclaims?

- In what ways do you successfully refute counterclaims? What other refutations might you include?

- Are there any counterclaims with which you agree? If so, how do you concede to them in your paper? In what ways does your discussion show fairness?

After completing your peer review and personal assessment, make necessary revisions based on these notes. See Annotated Student Sample an example of a student’s argumentative research essay. Note how the student

- presents the argument;

- supports the viewpoint with reasoning and evidence;

- includes support in the form of facts, opinions, paraphrases, and summaries;

- provides citations (correctly formatted) about material from other sources in the paper;

- uses ethos, pathos, and logos throughout the paper; and

- addresses counterclaims (dissenting opinions).

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/10-5-writing-process-creating-a-position-argument

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Writing a Position Paper: A Student’s Guide to Success

You know those moments when you’re trying to explain your side of an argument, and the other person just doesn’t get it? That’s kind of what a position paper is, except on a bigger stage, with higher stakes.

Writing a position paper means putting together facts, research, and a perspective so compelling that readers can’t help but take notice. Whether it’s for class, a conference, or even a mock debate, a great position paper shows you’re not just informed — you’re ready to lead the conversation.

Writing one isn’t like rattling off your thoughts in a group chat, though. You need focus, structure, and evidence to make your case. But don’t worry, we’re about to explore how to write a position paper with clear steps, examples, and tips that’ll make it something you’re actually proud to submit.

Need some extra help pulling it all together? Check out our qualified essay writers for hire here (because sometimes, it’s okay to let the pros take over!).

What is a Position Paper

A position paper is a written presentation of your stance on a specific issue, supported by evidence and analysis. Think of it as your chance to show you’ve done the research, understood the issue from all angles, and have something meaningful to say.

For instance, if the topic is climate change, a position paper might argue for renewable energy adoption. It wouldn’t stop at saying, “Renewables are better” ; it would add statistics about carbon emissions, case studies of successful green initiatives, and expert opinions.

In academic settings, position papers test your ability to think critically, argue persuasively, and communicate effectively. They’re also a tool for dealing with real-world problems — skills you’ll use far beyond the classroom.

Purpose of a Position Paper

Position papers are about making an impact. Their purpose is to take an issue and argue your case with clarity and confidence. Whether you’re advocating for change or explaining a complex topic, position papers help others see the issue from your perspective.

.webp)

Here’s what a position paper does:

- Advocates : Let’s say you’re passionate about mental health in schools. A position paper could argue for more funding, backed by stats on how it helps students thrive.

- Persuades : You have opinions, but the goal is to make others see your point of view using solid evidence and examples.

- Educates : Break down big, messy issues like climate change or AI ethics into something people can actually understand.

- Solves Problems : If there’s an issue (like rising student debt), a position paper is where you suggest real, actionable solutions.

- Analyzes Policies : Have thoughts on government policies? Use a position paper to explore what’s working, what’s not, and what needs to change.

Position papers also have a simple structure: state your argument, support it with evidence, tackle counterarguments, and finish strong. They’re used in everything from academic settings to debates, government meetings, and even business discussions.

Wednesday Addams

Mysterious, dark, and sarcastic

You’re the master of dark humor and love standing out with your unconventional style. Your perfect costume? A modern twist on Wednesday Addams’ gothic look. You’ll own Halloween with your unapologetically eerie vibe. 🖤🕸️

We Write, You Win

Get a professional position paper that’s persuasive, polished, and ready to impress. Let our experts handle the writing for you.

Position Paper Structure

Knowing how to structure a position paper makes everything so much easier. You’ll know exactly where to start, what to include, and how to wrap it up so your argument hits home.

.webp)

Introduction

The introduction is your chance to hook the reader and set the stage for everything that follows. Start strong and keep it clear:

- Hook : Begin with something that grabs attention. Maybe it’s a surprising fact, a bold statement, or a story that makes the topic feel real. For example: “Every minute, a truckload of plastic enters the ocean that’s enough to fill a football field every single day.”

- Background : Help your reader understand why this matters. Give a quick rundown of the issue, keeping it simple but meaningful. “Plastic pollution has been piling up for decades, and it’s now threatening marine life, ecosystems, and even human health as microplastics end up in our food and water.”

- Thesis Statement : Get to the point. Clearly say where you stand and what you’ll argue in your paper. “The only way to tackle this crisis is by banning single-use plastics and investing in reusable alternatives on a global scale.”

- Roadmap (Optional) : Let them know what to expect. “In this paper, we’ll look at the environmental damage caused by plastic, examine current efforts to reduce waste, and explore practical solutions to make a real difference.”

Body Paragraphs

The body of your position paper is where the real work happens. Each paragraph takes a single idea, backs it up with evidence, and ties it to your thesis. Here’s how to make each one count and stick to a clear position paper format:

- Topic Sentence : Start with a clear sentence that tells the reader what this paragraph is about. For example: “Plastic pollution poses a direct threat to marine life, with devastating consequences.”

- Supporting Evidence : Bring in facts, stats, or expert opinions that prove your point. For instance: “According to a study by the World Wildlife Fund, over 100,000 marine animals die every year from plastic entanglement or ingestion.” Be specific and use credible sources — this is your proof.

- Analysis : Explain the facts. Why does this evidence matter? Tie it back to your thesis. “This highlights the urgent need for strict global regulations to limit plastic production, as the harm to biodiversity has cascading effects on ecosystems and human industries like fishing.”

- Counterargument and Rebuttal : Address opposing views, but don’t let them win. For example: “Some argue that plastic bans harm businesses. However, many companies have successfully transitioned to sustainable alternatives, like compostable packaging, proving that eco-friendly doesn’t mean unprofitable.”

Keep the flow going. End one paragraph smoothly and connect it to the next so your paper reads naturally.

Building strong arguments doesn’t have to be a solo mission. Let our argumentative essay helper step in and make it easier for you.

The conclusion is where you wrap it all up and leave your reader with something to think about. Keep it clear, confident, and focused.

- Restate Your Thesis : Remind the reader what you’ve been arguing all along. “If we want to deal with the plastic crisis, we need to cut back on single-use plastics, push for better alternatives, and enforce stricter policies.”

- Summarize Key Points : Quickly hit the highlights of your argument. “We’ve looked at how plastic pollution is wrecking marine life, how current efforts aren’t enough, and why shifting to sustainable materials can make a real difference.”

- Call to Action : Leave your reader with the next step. “It’s time to act. Start by cutting down your own plastic use, support businesses that go green, and speak up for stronger environmental laws.”

Position Paper Structure Example

Let’s look at another position paper example to see how everything fits together. Here’s how you would structure a paper arguing for universal basic income (UBI):

- Hook : “Nearly 10% of the global population lives on less than $2 a day. UBI could change that.”

- Background : “Universal basic income is a system where every citizen receives a regular, unconditional payment to meet their basic needs, a concept gaining traction worldwide.”

- Thesis : “To address income inequality and improve quality of life, governments must adopt universal basic income policies.”

- Topic Sentence : “UBI has proven to reduce poverty in pilot programs.”

- Evidence : “In Finland’s UBI experiment, recipients reported lower stress levels, better mental health, and improved job prospects.”

- Analysis : “By providing financial stability, UBI allows people to focus on education, health, and employment opportunities.”

- Counterargument and Rebuttal : “Critics argue it’s too expensive, but reallocating subsidies and cutting bureaucratic costs make it feasible.”

- Topic Sentence : “UBI can boost local economies by increasing consumer spending.”

- Evidence : “A study in Kenya found that cash transfers significantly increased spending in local markets, benefiting businesses and communities.”

- Analysis : “This economic stimulation creates a ripple effect, improving livelihoods far beyond the individual recipients.”

- Counterargument and Rebuttal : “Some worry it disincentivizes work, but research shows recipients still seek employment, using UBI as a safety net.”

- Restate Thesis : “Universal basic income is a practical, proven solution to combat poverty and boost economies.”

- Call to Action : “It’s time for policymakers to stop debating and start piloting UBI at scale to create a fairer future.”

Want to skip the heavy lifting? You can buy a persuasive essay that’s tailored to your exact topic and tone.

How to Write a Position Paper

Writing a position paper might seem like an intimidating task, but it’s really just a chance to voice your opinion in a well-organized way. Daunting? Maybe. Doable? Absolutely. The secret lies in breaking it down into manageable steps and keeping your focus sharp.

Some fields to explore for position paper topics:

- Technology and its ethical implications (e.g., AI regulation).

- Environmental strategies like sustainable farming or urban green spaces.

- Economic solutions such as universal basic income or tax reform.

- Education reforms, like addressing student loan debt.

- Public health policies, such as mandatory vaccinations.

Conduct Thorough Research

Solid research makes or breaks a position paper, so don’t cut corners. Start by reading reliable sources — think academic journals, books, and legit websites (no Wikipedia citations, please). The more credible your evidence, the stronger your argument.

As you gather info, be picky. Not all sources are created equal. A peer-reviewed study is Perfect. A random blog with zero citations is a hard pass. Look for facts that directly back your point and avoid anything biased or outdated.

Keep track of everything. Whether it’s a notebook, Google Docs, or sticky notes all over your desk, stay organized. It’ll save you so much stress when it’s time to write.

Develop a Strong Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement is the heart of your paper. It’s the one sentence that sums up your argument and sets the tone for everything else. When you’re writing a position paper, make it clear, specific, and debatable. Here’s how:

- Be Clear and Concise : Don’t dance around your point. Say it directly. “Renewable energy is the key to combating climate change.”

- Make It Argumentative : Your thesis should spark debate, not state the obvious. “Government subsidies for renewable energy are essential for reducing carbon emissions.”

- Stay Specific : Narrow it down. Broad claims are too hard to back up. Instead of “Education needs reform,” go for “Reducing class sizes improves student performance in public schools.”

- Avoid Fluff : Phrases like “I believe” or “In my opinion” weaken your thesis. Own your argument.

Structure Your Paper

We’ve already covered the key elements of a position paper’s structure, so this is just a quick reminder to stick to the framework. Your paper should have a clear introduction, strong body paragraphs, and a focused conclusion.

Getting the structure right makes all the difference. Dive into the argumentative essay format for tips that actually work.

Write Clearly and Concisely

Clarity is everything when writing a position paper. Here’s how to nail it:

- Use Simple Language : Skip the fancy words unless they’re absolutely necessary. Instead of “utilize,” just say “use.” Your goal is to be understood, not to sound like a thesaurus.

- Get to the Point : Nobody needs three sentences when one will do. “The policy is ineffective” beats “The policy lacks effectiveness due to multiple inefficiencies.”

- Strong Transitions : Make your paper flow. Use words like “however,” “therefore,” or “in contrast” to guide your reader from one point to the next.

- Edit Ruthlessly : After writing, go back and trim unnecessary words. Think of it as decluttering your argument — it makes everything sharper and easier to follow.

Cite Your Sources

Citing your sources is non-negotiable. It’s how you show you’ve done the work and give credit where it’s due.

- Follow a Style Guide : Whether it’s APA, MLA, or Chicago, stick to the rules. Tools like Zotero or Citation Machine can help.

- Be Consistent : Pick one style and stick with it. Mixing formats looks sloppy and confuses readers.

- Avoid Plagiarism : Always give credit to the original authors. If you paraphrase, cite it. If it’s a direct quote, use quotation marks and cite it.

Bonus tip: Keep track of sources as you research. Nothing’s worse than hunting down a reference at 2 a.m. Proper citations = credibility.

Proofread and Edit

Once you’ve written your paper, don’t just hit submit. Editing is where the magic happens.

- Check for Errors : Scan for grammar, punctuation, and spelling mistakes. Typos can make even the best position paper ideas look careless. Tools like Grammarly are lifesavers here.

- Read Aloud : Hearing your words helps spot awkward sentences or confusing phrasing. If it doesn’t flow out loud, it won’t read well either.

- Get Feedback : A fresh set of eyes can catch things you’ve missed. Share your paper with a friend or classmate who knows the topic, or ask a teacher for a quick review.

Besides, take a break before editing. Coming back with fresh eyes makes it easier to catch mistakes and improve clarity.

Position Paper Example

Here’s an example of a position paper to show how everything comes together, with a clear structure, strong arguments, and credible evidence. Use this as a guide to write your own compelling paper.

Tips for Writing Effective Position Papers

Writing a position paper doesn’t have to be stressful. It’s all about laying out your argument in a way that’s easy to follow and hard to argue against. Here’s how to make sure your position paper is clear, strong, and straight to the point:

Your position paper should sound like you know your stuff, and it should make your reader say, “That makes sense.” Keep it real, back it up, and don’t overthink it. Writing with clarity and confidence always wins.

Not sure where to start? Check out these unique argumentative essay topics and find something that sparks your interest.

The Final Word

Writing a position paper is your chance to showcase your ideas, backed by solid evidence and clear reasoning. Stay focused, write with confidence, and remember to stick to the structure. Whether it’s for class or the real world, a well-written position paper has the power to spark conversations, influence decisions, and make your voice heard.

So, take these tips and write something you’re proud of!

Your Ideas, Perfectly Written

Share your topic, and we’ll write a custom position paper that highlights your perspective with expert research and structure.

What Is the Main Purpose of a Position Paper?

What to avoid in writing position papers, what’s the difference between a position paper and an argumentative essay.

Annie Lambert

specializes in creating authoritative content on marketing, business, and finance, with a versatile ability to handle any essay type and dissertations. With a Master’s degree in Business Administration and a passion for social issues, her writing not only educates but also inspires action. On EssayPro blog, Annie delivers detailed guides and thought-provoking discussions on pressing economic and social topics. When not writing, she’s a guest speaker at various business seminars.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

University of Toronto Model United Nations. (n.d.). Position Papers . University of Toronto. https://www.utmun.org/position-papers

Colorado State University. (n.d.). Position Papers: Writing Arguments for Specific Audiences . Colorado State University. https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/teaching/co301aman/pop8a1.cfm

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Position Argument

In a position argument, your purpose is to present a perspective, or viewpoint, about a debatable issue and persuade readers that your perspective is correct or at least worthy of serious consideration. A debatable issue is one that is subject to uncertainty or to a difference of opinion; in college classes, a debatable issue is one that is complex and involves critical thinking. These issues are not rooted in absolutes; instead, they invite writers to explore all sides to discover the position they support. In examining and explaining their positions, writers provide reasoning and evidence about why their stance is correct.

Many people may interpret the word argument to mean a heated disagreement or quarrel. However, this is only one definition. In writing, argument —or what Aristotle called rhetoric —means “working with a set of reasons and evidence for the purpose of persuading readers that a particular position is not only valid but also worthy of their support.” This approach is the basis of academic position writing.

Note: It is also important to note, however, that the term rhetoric is flexible and has other meanings in the English field involving written, verbal, spatial, and even visual communication, among others.

Overview of a Position Argument

Your instructor likely will require your position argument to include the following elements, which resemble those of Aristotle’s classical argument. However, as you continue the development of your writing identity throughout your composition endeavors, consider ways in which you want to support these conventions or challenge them for rhetorical purposes.

- Introduce the issue and your position on the issue

- Explain and describe the issue

- Address the opposition

- Provide evidence to support your position

- Offer your conclusion

Position arguments must provide reasoning and evidence to support the validity of the author’s viewpoint. By offering strong support, writers seek to persuade their audiences to understand, accept, agree with, or take action regarding their viewpoints. In a college class, an audience is usually an instructor and other classmates. Outside of an academic setting, however, an audience includes anyone who might read the argument—employers, employees, colleagues, neighbors, and people of different ages or backgrounds or with different interests.

Before you think about writing, keep in mind that presenting a position is already part of your everyday life. You present reasoning to frame evidence that supports your opinions, whether you are persuading a friend to go to a certain restaurant or persuading your supervisor to change your work schedule. Your reasoning and evidence emphasize the importance of the issue—to you. Position arguments are also valuable outside of academia. Opinion pieces and letters to the editor are essentially brief position texts that express writers’ viewpoints on current events topics. Moreover, government organizations and political campaigns often use position arguments to present detailed views of one side of a debatable issue.