What is Video Research?

By Insight Platforms

- Video Research

- Video Diary Studies

- Video Analytics

- Webcam Groups

- Agile Qualitative Research

- Webcam Interviews

- Facial Coding

- NLP (Natural Language Processing)

- User Testing

- User Experience (UX) Research

This article will explore what video research is, its benefits and uses, alongside ways of analysing and sharing findings.

The use of video has exploded in the last decade. YouTube boasts shy of 3 billion active monthly users, and people watch over a billion hours of video every day. Just on YouTube. Let that sink in for a moment. And that’s not taking into account videos watched on other social media platforms.

This trend towards video has been amplified since the recent global pandemic. Even technophobes have been involved in Zoom meetings and conferences, virtual quizzes, and spoken to friends and family on FaceTime.

Video is here to stay. It has become fundamental to how we communicate. But how can that be translated into research?

Video can be a great way of getting high-quality insight. It can help us better understand people by observing their needs, attitudes and behaviour (rather than just asking questions). But getting to that quality insight might be time-consuming, expensive, and overwhelming.

However, while that used to be true, technological advancements have massively improved the ability to use video for research purposes. It enables easier capture of video, easier analysis, and easier sharing.

This article is broken into 3 parts:

- How you can start using video to capture data to enhance your market and user research.

- Ways to analyse video research.

- How you can use video to create compelling outputs.

Part 1: Capturing Video Data

Here are some examples of how and why you would collect video data. This won’t be exhaustive – uses for video research are growing all the time, but this should give some inspiration.

Live Streaming In-Person Focus Groups

Sometimes travel is not feasible. Other times, there’s a finite number of people who sit in a viewing facility or no viewing facility at all.

By streaming focus groups you retain the benefits of traditional face-to-face qual while allowing for more people to witness the conversations. This can increase involvement and engagement with stakeholders, and encourages wider collaboration.

Mobile Video Capture

This method asks research participants to capture videos, whether that be their behaviour, thoughts and feelings about certain topics. This could be either through video diaries, or through mobile ethnography .

There are several benefits of mobile ethnography vs. traditional ethnography. It is often a lot cheaper and can be scaled to a larger number of participants. It also usually provides access to results in real time. Additionally, behaviour is likely to be more natural than when you have a researcher physically observing you.

Video Focus Groups

Video focus groups offer a layer of flexibility that physical focus groups can’t. Research participants are asked to join a virtual room at a set time with their webcams. It typically includes a similar number of participants to traditional focus groups (somewhere between 6-12), and has a similar format.

This method offers a range of benefits. It allows for more diversity in the group. Participants can live anywhere in the world to take part, provided they have access to a webcam and an internet connection. This also makes it easier to involve people in remote areas, which is often not feasible with face-to-face methodologies.

It also lets you integrate different participant engagement, such as polls, stimulus annotation, and private chats. You can share videos, links and stimulus easily, and all interactions are automatically recorded.

Video Response Open-Ends

Open-ended questions are a staple in survey research. However, it is a great idea to give people the option to answer with a video instead.

According to Medallia ’s LivingLens , people use 6x more words in a video response than they do in a written response. This means you get far more depth to an answer, and often access to insight you otherwise wouldn’t.

Additionally, allowing people to answer with video is a more inclusive approach. Typed open-ended answers can be a challenge for some; particularly if they have physical difficulties with typing or learning difficulties with spelling. By providing people with alternative ways to answer, you gain a deeper understanding of experiences that may otherwise be missed.

Fixed Camera Observations

This is a way of running ethnographies without sending a person to actually observe. A camera is set up in a home, for instance in a person’s kitchen, and the natural behaviour is monitored.

This method has a few benefits. It doesn’t rely on participants remembering to record their own behaviour – a pitfall for some mobile ethnography. It also limits disrupting natural behaviour. Once the camera is set up it’s likely forgotten about, which is a challenge if there’s another person in the room watching you.

In-the-Moment OOH Behaviour

Participants are given portable cameras, like Go-Pros, and asked to take them out and about with them. This footage is then analysed to monitor OOH behaviour.

This has a variety of uses. It can measure how people navigates stores to show the customer journey. It also has applications with events, to understand where people have been within a venue and what they’ve been exposed to.

Additionally, it’s reasonably easy to provide someone with the necessary equipment making it easier to scale than with accompanied research. Behaviour is also likely to be true to normal, and uninfluenced by the researcher.

In-Store Cameras

For this method, a fixed camera is set up in a store and observes behaviour. It can be used to understand how people navigate a store. Alternatively it can monitor a specific aisle or store feature (like a POS display).

This method is simple to set up, and means that the conditions are consistent for each shopper. It is also a more natural way of observing behaviour, and doesn’t require a researcher to physically be in the store. This allows you to scale your approach, by adding more stores, without adding more researchers. This also enables research in harder to reach areas, which can be useful if you want to understand emerging markets.

Facial Reactions / Facial Coding

What people say they think and what they actually think aren’t always one in the same. Facial reactions can give us a wealth of information about someone’s initial response to something. This method uses a camera, typically a webcam, to record someone’s reactions to a stimulus.

This is particularly useful for video advertising. By recording people’s authentic responses you can see slight facial expressions that could be the difference between being engaged and not. Do they sit forward when they are shown advert? Do they roll their eyes at a product claim?

Thankfully, there now a host of different tools available that can automate the process of understanding these slight nuances. We will discuss this further, though a good place to start is with this demo from Element Human .

Screen Capture with Front Facing Video

Video can be really useful for UX research. By recording how people navigate your site while simultaneously recording their facial expressions you can identify pain points or anything that delights users.

Similar to facial coding above, this method provides meaning behind micro expressions. You can measure the emotions users have while they use your site or app. For instance, a furrowed brow while searching for an option showing confusion is detail that could not be picked this up with screen capture alone.

Part 2: Analysing Video Data

So you’ve captured your video, now you need to understand its contents.

Here are some of the AI-powered analytics tools that make light work of analysing video data.

Automated Transcriptions

Many platforms provide automatic transcriptions for videos uploaded. This can be incredibly useful, especially if there are large quantities of video to analyse. This then allows you to use text analytics tools to help you navigate themes. If this is coupled with features that automatically time stamp quotes to the video then you can easily watch back pertinent points.

Automated Translations

This is a great feature if you are running video research in a variety of markets. Automated translations work in a similar way to automated transcriptions, but instead help you review all the content across the different markets in your native language.

This is sometimes offered alongside subtitles, which can be great for show reels that demonstrate different responses across multiple markets.

Facial / Emotion Coding

This looks at the different video and identifies key emotions throughout the clip by analysing facial expressions. If the platform allows, you can then find moments where this emotion has been exhibited and review the context in which it was felt. Additionally, you can see what percentage of your participants have the same emotions by topics, or filter responses based on that emotion.

Object Recognition

Object recognition identifies objects within a video, such as products, brands, or items. It can also help you understand the context in which the object was shown.

This is very useful for a range of different video research. It is great for diary studies, by measuring the different products that are shown. For in-store video monitoring, it can identify which products customers put in their basket or pick up to look at.

This, again, makes it quicker and easier to find what you are looking for. It can also measure the number of times an item has appeared in video helping to quantify unstructured data.

Sentiment Analysis

While facial coding looks at expressions to understand how people implicitly feel, sentiment analysis measures how they explicitly feel by analysing language.

It can show how positively or negatively someone talks about certain topics. It can sometimes be very granular, for instance a person might speak positively about a category, but negatively about a specific product.

Sentiment analysis can give you an overview which helps summarise your data.

Part 3: Video Research Outputs

Once you’ve analysed your video research data you’ll want to create outputs that help tell impactful stories to your stakeholders. There are two main avenues for this.

Video Presentation

I once heard that video for research can either be used for exploration, or for presentation. That is no longer the case.

The Field Notes platform helps create high quality user generated content (watch the demo here ). It gives clear instructions to participants about how to make good videos, meaning content can be used to provide insight on a topic and to illustrate your story.

Additionally, Medallia ’s LivingLens has a built-in feature which allows you to put together and edit show reels with video excerpts from a range of research participants, making video editors out of us all.

Creating an illustrative video montage is a great use of this data. Video is more compelling and more memorable than traditional presentations, and plays to the strengths of the method.

You can also use the data that you have gathered to create compelling presentations. Many platforms will offer a range of exportable outputs such as quantitative charts, word clouds, sentiment analysis data, segmentations, and illustrative clips.

These can all add a lot of depth to your video research and help summarise the wealth of information that you may have gathered in an easily digestible format.

Mike Stevens

Leave a comment cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Change Location

Find awesome listings near you.

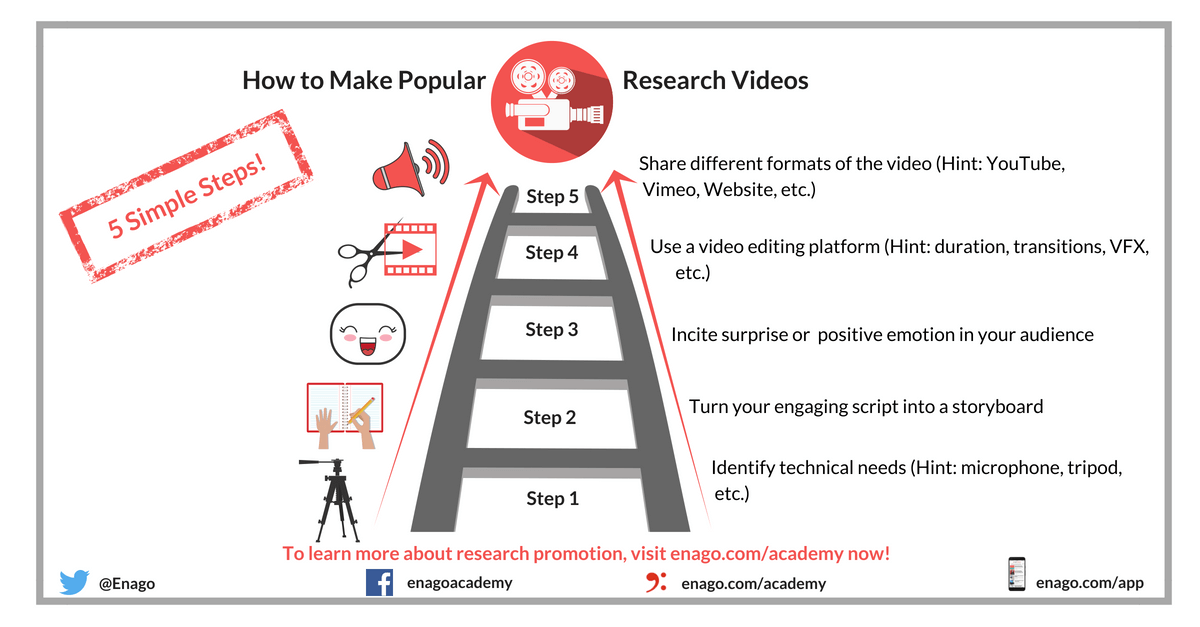

The 8 Science Video Types Every Researcher Should Master

Once upon a time in a bustling university, a group of dedicated PhD students and researchers worked hard in their labs, uncovering groundbreaking findings that had the potential to change the world. And while their data was revolutionary, their groundbreaking work lingered in the shadows, buried under jargon and complex figures, struggling to reach beyond the academic ivory tower.

But then, they stumbled upon the untapped goldmine of science communication through video, a medium that promised to bridge the gap between their research and the public. Therefore, they embarked on a journey to transform their dense papers into captivating stories, using the power of video to illuminate their discoveries and share their knowledge with the world.

Now, it's your turn to explore the goldmine of science video types that can catapult your research into the spotlight.

1. The Thrill of Video Competitions

First up, let's talk about video competitions. Yes, they're a thing, and yes, they're as cool as they sound. From your home institution to global scientific societies, there's a treasure trove of contests begging for your ingenious video submissions. Ever heard of the Visualise Your Thesis Competition? It's like the Olympics for PhD students' videos, and it's just as rewarding.

And hey, winning up to 5,000 euros in the Nature Awards: Science in Shorts isn't too shabby either. And you know what’s useful about competitions? Deadlines. Nothing lights a fire under you quite like a ticking clock ⏰. Participating in—and winning!—a science video competition during my PhD days was the catalyst for my passion for science communication. It's an incredibly rewarding experience that I wholeheartedly recommend!

Need some inspiration? Why not checking out the past winning videos? This one is one of my favourites 👇

Visualise Your Thesis 2022 winner - Drew Cylinder - Neural correlates of behavioural changes

2. Video Applications: The New Cover Letter

Competitions aside, let's chat about video applications. Whether it's for that grant you've been eyeing or your dream job, the world's moving away from heavy written applications to dynamic videos. At Animate Your Science, for instance, we ditched written cover letters ages ago.

Why? Because if a picture's worth a thousand words, a video's worth infinitely more. However, bear in mind that not all organisations are riding the wave of innovation; some still prefer traditional methods and might not accept video applications at all. It's crucial to check the submission guidelines of each organisation to ensure your application meets their standards.

Want to see a brilliant example of how a video can land you a score of job offers? Meet Marta and her viral personal intro video 👇

3. Conference Presentations: The Virtual Stage

Ah, the pandemic pivot – while many conferences have eagerly returned to their in-person traditions, a significant number have embraced the virtual format or a hybrid approach. This shift means you could be delivering your next presentation without stepping outside your home. And for those times when life throws a curveball – maybe you're under the weather or out doing fieldwork – a pre-recorded presentation can step in, ensuring your research still hits the spotlight, no matter where you are.

4. Lab and Research Explainer Videos

Think of this as your research's elevator pitch to the world. Whether you're showcasing your lab's world-changing work or explaining your field's biggest questions, a well-crafted explainer video can make your work accessible and intriguing to potential funders, investors, collaborators, students and the public. Such a video shouldn't just be a part of your communication dinner spread; it should be the main dish!

Embed it right at the top of your personal or lab's website, ensuring it's the first thing visitors see. Likewise, pin it as the top post on your social media profiles to capture the attention of your network from the get-go. This strategy ensures your key message is unmissable, amplifying your reach and impact.

Need an example? Check out the video we produced for the Gillanders Lab 👇

5. Social Media: Your Research's Megaphone

From the short videos of TikTok to the in-depth explorations on YouTube, social media is your research's ticket to visibility. Pick your platform, find your voice, and don't be afraid to start small. The key? Just start. Every top account started with 0 followers.

For some inspo see how this climate scientist is doing her bit by informing the public about the latest climate research with her YouTube channel 👇

6. Video Abstracts: The Teaser Trailer

With studies showing a significant boost in citations and engagement for papers with video abstracts, overlooking this tool is akin to bypassing an investment with a high return rate. Sure, it requires some initial effort, but the potential payoff in terms of visibility and impact is immense. Why miss out on that opportunity?

Crafting video abstracts is our specialty, and we're proud of it. Dive into our portfolio with this example we created on the elusive DNA pick-pocket bacterium 🥷. Take a peek here 👇

7. Screen Recording Tutorials: Show, Don't Tell

Ever tried explaining a complex process over email? It's about as fun as watching paint dry. Enter screen recording. Whether it's a new software trick or a data analysis walkthrough, showing how something works beats a lengthy written explanation every time. Plus, it's a gift that keeps on giving, saving you from endless repeat explanations. Get onto the free plan of Loom and thank me later. 😉

8. Video Research Papers

Method papers can often be dense and hard to follow. Video research papers change the game, turning complex procedures into digestible, visual instructions. This not only makes your research more accessible but also easier to replicate, meaning more citations for you 😉. JOVE is the go-to platform for both publishing and discovering these video papers.

So, What's Next?

There you have it, eight types of videos await to transform your academic presence. These insights are designed to lift your work from obscurity to spotlight, inviting engagement and dialogue.

I hope this blog post ignited your enthusiasm for the power of video in science communication. If the thought of creating your own video seems daunting, don't worry. I've condensed over a decade of science communication wisdom into my online course, ' Lights, Camera, Impact! How to Produce Captivating Science Videos. ' This course offers a step-by-step approach to crafting videos that can make your research shine.

Take the leap and learn to narrate your scientific discoveries with impact. Enrol in ' Lights, Camera, Impact! ' and start your journey to masterful science storytelling.

Related Posts

How to promote your research in the media with a video abstract

How to Make Cool Animated Science Videos in PowerPoint

How to transform your research into a compelling science story!

VideoPrism: A foundational visual encoder for video understanding

February 22, 2024

Posted by Long Zhao, Senior Research Scientist, and Ting Liu, Senior Staff Software Engineer, Google Research

Quick links

- Copy link ×

An astounding number of videos are available on the Web, covering a variety of content from everyday moments people share to historical moments to scientific observations, each of which contains a unique record of the world. The right tools could help researchers analyze these videos, transforming how we understand the world around us.

Videos offer dynamic visual content far more rich than static images, capturing movement, changes, and dynamic relationships between entities. Analyzing this complexity, along with the immense diversity of publicly available video data, demands models that go beyond traditional image understanding. Consequently, many of the approaches that best perform on video understanding still rely on specialized models tailor-made for particular tasks. Recently, there has been exciting progress in this area using video foundation models (ViFMs), such as VideoCLIP , InternVideo , VideoCoCa , and UMT . However, building a ViFM that handles the sheer diversity of video data remains a challenge.

With the goal of building a single model for general-purpose video understanding, we introduce “ VideoPrism: A Foundational Visual Encoder for Video Understanding ”. VideoPrism is a ViFM designed to handle a wide spectrum of video understanding tasks, including classification, localization, retrieval, captioning, and question answering (QA). We propose innovations in both the pre-training data as well as the modeling strategy. We pre-train VideoPrism on a massive and diverse dataset: 36 million high-quality video-text pairs and 582 million video clips with noisy or machine-generated parallel text. Our pre-training approach is designed for this hybrid data, to learn both from video-text pairs and the videos themselves. VideoPrism is incredibly easy to adapt to new video understanding challenges, and achieves state-of-the-art performance using a single frozen model.

VideoPrism is a general-purpose video encoder that enables state-of-the-art results over a wide spectrum of video understanding tasks, including classification, localization, retrieval, captioning, and question answering, by producing video representations from a single frozen model.

Pre-training data

A powerful ViFM needs a very large collection of videos on which to train — similar to other foundation models (FMs), such as those for large language models (LLMs). Ideally, we would want the pre-training data to be a representative sample of all the videos in the world. While naturally most of these videos do not have perfect captions or descriptions, even imperfect text can provide useful information about the semantic content of the video.

To give our model the best possible starting point, we put together a massive pre-training corpus consisting of several public and private datasets, including YT-Temporal-180M , InternVid , VideoCC , WTS-70M , etc. This includes 36 million carefully selected videos with high-quality captions, along with an additional 582 million clips with varying levels of noisy text (like auto-generated transcripts). To our knowledge, this is the largest and most diverse video training corpus of its kind.

Two-stage training

The VideoPrism model architecture stems from the standard vision transformer (ViT) with a factorized design that sequentially encodes spatial and temporal information following ViViT . Our training approach leverages both the high-quality video-text data and the video data with noisy text mentioned above. To start, we use contrastive learning (an approach that minimizes the distance between positive video-text pairs while maximizing the distance between negative video-text pairs) to teach our model to match videos with their own text descriptions, including imperfect ones. This builds a foundation for matching semantic language content to visual content.

After video-text contrastive training, we leverage the collection of videos without text descriptions. Here, we build on the masked video modeling framework to predict masked patches in a video, with a few improvements. We train the model to predict both the video-level global embedding and token-wise embeddings from the first-stage model to effectively leverage the knowledge acquired in that stage. We then randomly shuffle the predicted tokens to prevent the model from learning shortcuts.

What is unique about VideoPrism’s setup is that we use two complementary pre-training signals: text descriptions and the visual content within a video. Text descriptions often focus on what things look like, while the video content provides information about movement and visual dynamics. This enables VideoPrism to excel in tasks that demand an understanding of both appearance and motion.

We conduct extensive evaluation on VideoPrism across four broad categories of video understanding tasks, including video classification and localization, video-text retrieval, video captioning, question answering, and scientific video understanding. VideoPrism achieves state-of-the-art performance on 30 out of 33 video understanding benchmarks — all with minimal adaptation of a single, frozen model.

Classification and localization

We evaluate VideoPrism on an existing large-scale video understanding benchmark ( VideoGLUE ) covering classification and localization tasks. We find that (1) VideoPrism outperforms all of the other state-of-the-art FMs, and (2) no other single model consistently came in second place. This tells us that VideoPrism has learned to effectively pack a variety of video signals into one encoder — from semantics at different granularities to appearance and motion cues — and it works well across a variety of video sources.

Combining with LLMs

We further explore combining VideoPrism with LLMs to unlock its ability to handle various video-language tasks. In particular, when paired with a text encoder (following LiT ) or a language decoder (such as PaLM-2 ), VideoPrism can be utilized for video-text retrieval, video captioning, and video QA tasks. We compare the combined models on a broad and challenging set of vision-language benchmarks. VideoPrism sets the new state of the art on most benchmarks. From the visual results, we find that VideoPrism is capable of understanding complex motions and appearances in videos (e.g., the model can recognize the different colors of spinning objects on the window in the visual examples below). These results demonstrate that VideoPrism is strongly compatible with language models.

We show qualitative results using VideoPrism with a text encoder for video-text retrieval (first row) and adapted to a language decoder for video QA (second and third row). For video-text retrieval examples, the blue bars indicate the embedding similarities between the videos and the text queries.

Scientific applications

Finally, we test VideoPrism on datasets used by scientists across domains, including fields such as ethology, behavioral neuroscience, and ecology. These datasets typically require domain expertise to annotate, for which we leverage existing scientific datasets open-sourced by the community including Fly vs. Fly , CalMS21 , ChimpACT , and KABR . VideoPrism not only performs exceptionally well, but actually surpasses models designed specifically for those tasks. This suggests tools like VideoPrism have the potential to transform how scientists analyze video data across different fields.

With VideoPrism, we introduce a powerful and versatile video encoder that sets a new standard for general-purpose video understanding. Our emphasis on both building a massive and varied pre-training dataset and innovative modeling techniques has been validated through our extensive evaluations. Not only does VideoPrism consistently outperform strong baselines, but its unique ability to generalize positions it well for tackling an array of real-world applications. Because of its potential broad use, we are committed to continuing further responsible research in this space, guided by our AI Principles . We hope VideoPrism paves the way for future breakthroughs at the intersection of AI and video analysis, helping to realize the potential of ViFMs across domains such as scientific discovery, education, and healthcare.

Acknowledgements

This blog post is made on behalf of all the VideoPrism authors: Long Zhao, Nitesh B. Gundavarapu, Liangzhe Yuan, Hao Zhou, Shen Yan, Jennifer J. Sun, Luke Friedman, Rui Qian, Tobias Weyand, Yue Zhao, Rachel Hornung, Florian Schroff, Ming-Hsuan Yang, David A. Ross, Huisheng Wang, Hartwig Adam, Mikhail Sirotenko, Ting Liu, and Boqing Gong. We sincerely thank David Hendon for their product management efforts, and Alex Siegman, Ramya Ganeshan, and Victor Gomes for their program and resource management efforts. We also thank Hassan Akbari, Sherry Ben, Yoni Ben-Meshulam, Chun-Te Chu, Sam Clearwater, Yin Cui, Ilya Figotin, Anja Hauth, Sergey Ioffe, Xuhui Jia, Yeqing Li, Lu Jiang, Zu Kim, Dan Kondratyuk, Bill Mark, Arsha Nagrani, Caroline Pantofaru, Sushant Prakash, Cordelia Schmid, Bryan Seybold, Mojtaba Seyedhosseini, Amanda Sadler, Rif A. Saurous, Rachel Stigler, Paul Voigtlaender, Pingmei Xu, Chaochao Yan, Xuan Yang, and Yukun Zhu for the discussions, support, and feedback that greatly contributed to this work. We are grateful to Jay Yagnik, Rahul Sukthankar, and Tomas Izo for their enthusiastic support for this project. Lastly, we thank Tom Small, Jennifer J. Sun, Hao Zhou, Nitesh B. Gundavarapu, Luke Friedman, and Mikhail Sirotenko for the tremendous help with making this blog post.

- Machine Intelligence

- Machine Perception

Other posts of interest

December 19, 2024

- Algorithms & Theory ·

- Climate & Sustainability ·

- General Science ·

- Generative AI ·

- Health & Bioscience ·

- Machine Intelligence ·

- Quantum ·

- Year in Review

December 12, 2024

December 10, 2024

- July 3, 2024

- Research & Metric

Video-Based Qualitative Research: Revolutionizing Insights with Visual Data

In the dynamic world of research methodologies, video-based qualitative research has emerged as a powerful tool, offering rich, visual insights that surpass traditional methods. Research and Metric, a pioneer in this field, is leading the charge with innovative techniques that unlock deeper understanding and more engaging data.

Understanding Qualitative Research

Qualitative research focuses on exploring phenomena through a subjective lens, seeking to understand the underlying reasons, opinions, and motivations. Unlike quantitative research, which relies on numerical data, qualitative research delves into the “how” and “why” of human behavior, providing nuanced insights that are often missed by quantitative methods.

Video-Based Qualitative Research

Video-based qualitative research involves using video recordings to capture participants’ behaviors, interactions, and environments. This approach allows researchers to observe and analyze non-verbal cues, contextual settings, and real-time dynamics, adding a rich layer of data that enhances the overall research quality.

The Evolution of Video-Based Research

The history of video-based research can be traced back to early ethnographic studies where researchers used film to document cultural practices. Over the decades, advancements in technology have made video recording more accessible and cost-effective, paving the way for its widespread adoption in various fields.

Benefits of Video-Based Qualitative Research

Enhanced data richness.

Video recordings provide a depth of data that written transcripts simply cannot match. The visual and auditory elements captured in videos offer a fuller picture of participants’ experiences, emotions, and environments.

Visual Contextualization

Seeing is believing. Videos offer a visual context that helps in better understanding the surroundings, body language, and interactions among participants, leading to more accurate interpretations.

Participant Engagement

Participants often find video recordings less intrusive and more engaging than traditional note-taking or audio recordings. This can lead to more natural behavior and richer data.

Applications of Video-Based Research

Educational settings.

In educational research, videos are used to observe classroom interactions, teaching methods, and student behaviors, providing valuable insights into effective educational practices and learning outcomes.

Healthcare Research

In healthcare, video-based research helps in studying patient-provider interactions, treatment processes, and patient behaviors in clinical settings, contributing to improved healthcare delivery and patient satisfaction.

Marketing and Consumer Insights

Marketers use video-based research to understand consumer behavior, preferences, and reactions to products or advertisements. This approach helps in creating more effective marketing strategies and improving customer experiences.

Techniques in Video-Based Qualitative Research

Ethnographic studies.

Ethnography involves immersive, long-term observation of participants in their natural environments. Videos enhance this method by capturing real-time interactions and behaviors, providing a comprehensive view of the studied phenomena.

Focus Groups

Video recordings of focus groups allow researchers to analyze group dynamics, individual responses, and non-verbal cues, leading to deeper insights into the collective and individual perspectives of participants.

One-on-One Interviews

Recording interviews on video helps in capturing the nuances of participants’ expressions, gestures, and tone, which can be crucial for interpreting their responses accurately.

Data Analysis in Video-Based Research

Coding and categorizing.

Analyzing video data involves coding and categorizing visual and auditory elements. This process helps in identifying patterns, themes, and significant insights from the recorded material.

Software Tools

Advanced software tools like NVivo and ATLAS.ti aid in managing, coding, and analyzing video data, making the process more efficient and comprehensive.

Interpreting Visual Data

Interpreting video data requires a keen eye for detail and an understanding of visual communication. Researchers must consider the context, non-verbal cues, and the interplay between different elements in the video.

Ethical Considerations

Informed consent.

Obtaining informed consent is crucial in video-based research. Participants must be fully aware of the recording process, its purpose, and how the data will be used and stored.

Privacy and Confidentiality

Ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants is paramount. Researchers must take measures to protect the identities and personal information of those involved in the study.

Challenges in Video-Based Research

Technical issues.

Technical challenges, such as poor video quality, inadequate recording equipment, or technical malfunctions, can hinder the research process and affect data quality.

Data Overload

Video recordings generate large amounts of data, which can be overwhelming to analyze. Efficient data management and analysis strategies are essential to handle the volume of information.

Best Practices for Conducting Video-Based Research

Preparing participants.

Preparing participants for video recording involves explaining the process, setting expectations, and addressing any concerns they might have to ensure a smooth and comfortable experience.

Effective Recording Techniques

Using high-quality recording equipment, ensuring good lighting and sound conditions, and positioning cameras to capture the necessary angles are crucial for obtaining clear and useful video data.

Analyzing Non-Verbal Cues

Non-verbal cues, such as body language, facial expressions, and gestures, provide valuable insights. Researchers must be skilled in interpreting these cues to fully understand participants’ behaviors and responses.

Research and Metric’s Offerings

Innovative techniques.

Research and Metric stands out by employing cutting-edge techniques in video-based qualitative research. Their innovative approaches include using multiple cameras for different angles, integrating video analysis software, and employing skilled analysts to interpret the data.

Case Studies and Success Stories

Research and Metric has a track record of successful projects across various fields. Their case studies highlight how video-based research has provided valuable insights and driven positive outcomes for clients.

The future of video-based qualitative research looks promising, with continuous advancements in technology and methodology. As researchers increasingly recognize the value of visual data, video-based research will continue to evolve, offering richer, more nuanced insights.

What is Video-Based Qualitative Research?

Video-based qualitative research involves using video recordings to capture and analyze participants’ behaviors, interactions, and environments, providing a richer data set compared to traditional methods.

How does Video-Based Research differ from traditional methods?

Unlike traditional methods that rely on written or audio data, video-based research captures visual and auditory elements, offering a more comprehensive view of participants’ experiences and behaviors.

What are the benefits of using video in qualitative research?

Benefits include enhanced data richness, visual contextualization, and increased participant engagement, leading to more accurate and insightful findings.

What ethical considerations are important in video-based research?

Key considerations include obtaining informed consent, ensuring privacy and confidentiality, and being transparent about how the data will be used and stored.

What are some common challenges in video-based qualitative research?

Challenges include technical issues, data overload, and the need for skilled interpretation of visual data to extract meaningful insights.

How does Research and Metric ensure the quality of their video-based research?

Research and Metric employs innovative techniques, uses high-quality equipment, and integrates advanced software tools to ensure the accuracy and depth of their video-based qualitative research.

Market Research Gets Faster: The Future of Business Intelligence

Global Economic Outlook 2025: A Data-Driven Perspective

Data Pipeline Management: Revolutionizing Market Research Insights

AI-Powered Survey Design: Leading Market Research Innovation

Revolutionizing Market Research: How Research and Metric Became an Industry Leader

The Digital Health Transformation: AR, VR, AI, Telemedicine, and Telehealth Revolutionizing Care

Blockchain Technology in Market Research

Mobile Market Research

Big Data and Predictive Analytics in Market Research

Hot Research Metrics to Enhance Research Performance

30 N Gould St Ste R Sheridan, WY 82801, USA

- [email protected]

- +1 (307) 776-3002

Case Studies

Evaluation of Patient Adherence to Medication Regimens for Chronic Diseases

To explore consumer preferences and purchasing behaviors regarding over-the-counter pain relief medications.

Assessing Physician Attitudes towards Digital Health Solutions

Sign up to newsletters, next steps: sync an email add-on.

- ©2024 Research & Metric C Corp

- Methodology

- Open access

- Published: 28 July 2018

Research as storytelling: the use of video for mixed methods research

- Erica B. Walker ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9258-3036 1 &

- D. Matthew Boyer 2

Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy volume 3 , Article number: 8 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

6 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Mixed methods research commonly uses video as a tool for collecting data and capturing reflections from participants, but it is less common to use video as a means for disseminating results. However, video can be a powerful way to share research findings with a broad audience especially when combining the traditions of ethnography, documentary filmmaking, and storytelling.

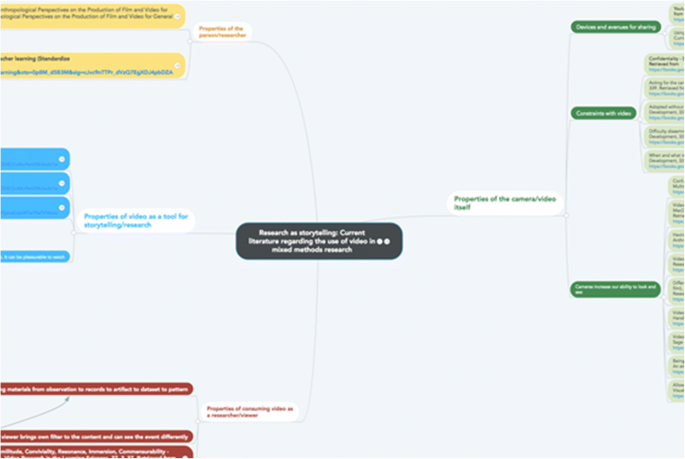

Our literature review focused on aspects relating to video within mixed methods research that applied to the perspective presented within this paper: the history, affordances and constraints of using video in research, the application of video within mixed methods design, and the traditions of research as storytelling. We constructed a Mind Map of the current literature to reveal convergent and divergent themes and found that current research focuses on four main properties in regards to video: video as a tool for storytelling/research, properties of the camera/video itself, how video impacts the person/researcher, and methods by which the researcher/viewer consumes video. Through this process, we found that little has been written about how video could be used as a vehicle to present findings of a study.

From this contextual framework and through examples from our own research, we present current and potential roles of video storytelling in mixed methods research. With digital technologies, video can be used within the context of research not only as data and a tool for analysis, but also to present findings and results in an engaging way.

Conclusions

In conclusion, previous research has focused on using video as a tool for data collection and analysis, but there are emerging opportunities for video to play an increased role in mixed methods research as a tool for the presentation of findings. By leveraging storytelling techniques used in documentary film, while staying true to the analytical methods of the research design, researchers can use video to effectively communicate implications of their work to an audience beyond academics and use video storytelling to disseminate findings to the public.

Using motion pictures to support ethnographic research began in the late nineteenth century when both fields were early in their development (Henley, 2010 ; “Using Film in Ethnographic Field Research, - The University of Manchester,” n.d ). While technologies have changed dramatically since the 1890s, researchers are still employing visual media to support social science research. Photographic imagery and video footage can be integral aspects of data collection, analysis, and reporting research studies. As digital cameras have improved in quality, size, and affordability, digital video has become an increasingly useful tool for researchers to gather data, aid in analysis, and present results.

Storytelling, however, has been around much longer than either video or ethnographic research. Using narrative devices to convey a message visually was a staple in the theater of early civilizations and remains an effective tool for engaging an audience today. Within the medium of video, storytelling techniques are an essential part of a documentary filmmaker’s craft. Storytelling can also be a means for researchers to document and present their findings. In addition, multimedia outputs allow for interactions beyond traditional, static text (R. Goldman, 2007 ; Tobin & Hsueh, 2007 ). Digital video as a vehicle to share research findings builds on the affordances of film, ethnography, and storytelling to create new avenues for communicating research (Heath, Hindmarsh, & Luff, 2010 ).

In this study, we look at the current literature regarding the use of video in research and explore how digital video affordances can be applied in the collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative human subject data. We also investigate how video storytelling can be used for presenting research results. This creates a frame for how data collection and analysis can be crafted to maximize the potential use of video data to create an audiovisual narrative as part of the final deliverables from a study. As researchers we ask the question: have we leveraged the use of video to communicate our work to its fullest potential? By understanding the role of video storytelling, we consider additional ways that video can be used to not only collect and analyze data, but also to present research findings to a broader audience through engaging video storytelling. The intent of this study is to develop a frame that improves our understanding of the theoretical foundations and practical applications of using video in data collection, analysis, and the presentation of research findings.

Literature review

The review of relevant literature includes important aspects for situating this exploration of video research methods: the history, affordances and constraints of using video in research, the use of video in mixed methods design, and the traditions of research as storytelling. Although this overview provides an extensive foundation for understanding video research methods, this is not intended to serve as a meta-analysis of all publications related to video and research methods. Examples of prior work provide a conceptual and operational context for the role of video in mixed methods research and present theoretical and practical insights for engaging in similar studies. Within this context, we examine ethical and logistical/procedural concerns that arise in the design and application of video research methods, as well as the affordances and constraints of integrating video. In the following sections, the frame provided by the literature is used to view practical examples of research using video.

The history of using video in research is founded first in photography and next in film followed more recently, by digital video. All three tools provide the ability to create instant artifacts of a moment or period of time. These artifacts become data that can be analyzed at a later date, perhaps in a different place and by a different audience, giving researchers the chance to intricately and repeatedly examine the archive of information contained within. These records “enable access to the fine details of conduct and interaction that are unavailable to more traditional social science methods” (Heath et al., 2010 , p. 2).

In social science research, video has been used for a range of purposes and accompanies research observation in many situations. For example, in classroom research, video is used to record a teacher in practice and then used as a guide and prompt to interview the teacher as they reflect upon their practice (e.g. Tobin & Hsueh, 2007 ). Video captures events from a situated perspective, providing a record that “resists, at least in the first instance, reduction to categories or codes, and thus preserves the original record for repeated scrutiny” (Heath et al., 2010 , p. 6). In analysis, these audio-visual recordings allow the social science researcher the chance to reflect on their subjectivities throughout analysis and use the video as a microscope that “allow(s) actions to be observed in a detail not even accessible to the actors themselves” (Knoblauch & Tuma, 2011 , p. 417).

Examining the affordances and constraints of video in research provides a researcher the opportunity to examine the value of including video within a study . An affordance of video, when used in research, is that it allows the researcher to see an event through the camera lens either actively or passively and later share what they have seen, or more specifically, the way they saw it (Chalfen, 2011 ). Cameras can be used to capture an event in three different modes: Responsive, Interactive, and Constructive. Responsive mode is reactive. In this mode, the researcher captures and shows the viewer what is going on in front of the lens but does not directly interfere with the participants or events. Interactive mode puts the filmmaker into the storyline as a participant and allows the viewer to observe the interactions between the researcher and participant. One example of video captured in Interactive mode is an interview. In Constructive mode, the researcher reprocesses the recorded events to create an explicitly interpretive final product through the process of editing the video (MacDougall, 2011 ). All of these modes, in some way, frame or constrain what is captured and consequently shared with the audience.

Due to the complexity of the classroom-research setting, everything that happens during a study cannot be captured using video, observation, or any other medium. Video footage, like observation, is necessarily selective and has been stripped of the full context of the events, but it does provide a more stable tool for reflection than the ever-changing memories of the researcher and participants (Roth, 2007 ). Decisions regarding inclusion and exclusion are made by the researcher throughout the entire research process from the initial framing of the footage to the final edit of the video. Members of the research team should acknowledge how personal bias impacts these decisions and make their choices clear in the research protocol to ensure inclusivity (Miller & Zhou, 2007 ).

One affordance of video research is that analysis of footage can actually disrupt the initial assumptions of a study. Analysis of video can be standardized or even mechanized by seeking out predetermined codes, but it can also disclose the subjective by revealing the meaning behind actions and not just the actions themselves (S. Goldman & McDermott, 2007 ; Knoblauch & Tuma, 2011 ). However, when using subjective analysis the researcher needs to keep in mind that the footage only reveals parts of an event. Ideally, a research team has a member who acts as both a researcher and a filmmaker. That team member can provide an important link between the full context of the event and the narrower viewpoint revealed through the captured footage during the analysis phase.

Although many participants are initially camera-shy, they often find enjoyment from participating in a study that includes video (Tobin & Hsueh, 2007 ). Video research provides an opportunity for participants to observe themselves and even share their experience with others through viewing and sharing the videos. With increased accessibility of video content online and the ease of sharing videos digitally, it is vital from an ethical and moral perspective that participants understand the study release forms and how their image and words might continue to be used and disseminated for years after the study is completed.

Including video in a research study creates both affordances and constraints regarding the dissemination of results. Finding a journal for a video-based study can be difficult. Traditional journals rely heavily on static text and graphics, but newly-created media journals include rich and engaging data such as video and interactive, web-based visualizations (Heath et al., 2010 ). In addition, videos can provide opportunities for research results to reach a broader audience outside of the traditional research audience through online channels such as YouTube and Vimeo.

Use of mixed methods with video data collection and analysis can complement the design-based, iterative nature of research that includes human participants. Design-based video research allows for both qualitative and quantitative collection and analysis of data throughout the project, as various events are encapsulated for specific examination as well as analyzed comparatively for changes over time. Design research, in general, provides the structure for implementing work in practice and iterative refinement of design towards achieving research goals (Collins, Joseph, & Bielaczyc, 2004 ). Using an integrated mixed method design that cycles through qualitative and quantitative analyses as the project progresses gives researchers the opportunity to observe trends and patterns in qualitative data and quantitative frequencies as each round of analysis informs additional insights (Gliner et al., 2009 ). This integrated use also provides a structure for evaluating project fidelity in an ongoing basis through a range of data points and findings from analyses that are consistent across the project. The ability to revise procedures for data collection, systematic analysis, and presenting work does not change the data being collected, but gives researchers the opportunity to optimize procedural aspects throughout the process.

Research as storytelling refers to the narrative traditions that underpin the use of video methods to analyze in a chronological context and present findings in a story-like timeline. These traditions are evident in ethnographic research methods that journal lived experiences through a period of time and in portraiture methods that use both aesthetic and scientific language to construct a portrait (Barone & Eisner, 2012 ; Heider, 2009 ; Lawrence-Lightfoot, 2005 ; Lenette, Cox & Brough, 2013 ).

In existing research, there is also attention given to the use of film and video documentaries as sources of data (e.g. Chattoo & Das, 2014 ; Warmington, van Gorp & Grosvenor, 2011 ), however, our discussion here focuses on using media to capture information and communicate resulting narratives for research purposes. In our work, we promote a perspective on emergent storytelling that develops from data collection and analysis, allowing the research to drive the narrative, and situating it in the context from where data was collected. We rely on theories and practices of research and storytelling that leverage the affordances of participant observation and interview for the construction of narratives (Bailey & Tilley, 2002 ; de Carteret, 2008 ; de Jager, Fogarty & Tewson, 2017 ; Gallagher, 2011 ; Hancox, 2017 ; LeBaron, Jarzabkowski, Pratt & Fetzer, 2017 ; Lewis, 2011 ; Meadows, 2003 ).

The type of storytelling used with research is distinctly different from methods used with documentaries, primarily with the distinction that, while documentary filmmakers can edit their film to a predetermined narrative, research storytelling requires that the data be analyzed and reported within a different set of ethical standards (Dahlstrom, 2014 ; Koehler, 2012 ; Nichols, 2010 ). Although documentary and research storytelling use a similar audiovisual medium, creating a story for research purposes is ethically-bounded by expectations in social science communities for being trustworthy in reporting and analyzing data, especially related to human subjects. Given that researchers using video may not know what footage will be useful for future storytelling, they may need to design their data collection methods to allow for an abundance of video data, which can impact analysis timelines as well. We believe it important to note these differences in the construction of related types of stories to make overt the essential need for research to consider not only analysis but also creation of the reporting narrative when designing and implementing data collection methods.

This study uses existing literature as a frame for understanding and implementing video research methods, then employs this frame as perspective on our own work, illuminating issues related to the use of video in research. In particular, we focus on using video research storytelling techniques to design, implement, and communicate the findings of a research study, providing examples from Dr. Erica Walker’s professional experience as a documentary filmmaker as well as evidence from current and former academic studies. The intent is to improve understanding of the theoretical foundations and practical applications for video research methods and better define how those apply to the construction of story-based video output of research findings.

The study began with a systematic analysis of theories and practices, using interpretive analytic methods, with thematic coding of evidence for conceptual and operational aspects of designing and implementing video research methods. From this information, a frame was constructed that includes foundational aspects of using digital video in research as well as the practical aspects of using video to create narratives with the intent of presenting research findings. We used this frame to interpret aspects of our own video research, identifying evidence that exemplifies aspects of the frame we used.

A primary goal for the analysis of existing literature was to focus on evidentiary data that could provide examples that illuminate the concepts that underpin the understanding of how, when, and why video research methods are useful for a range of publishing and dissemination of transferable knowledge from research. This emphasis on communicating results in both theoretical and practical ways highlighted areas within the analysis for potential contextual similarities between our work and other projects. A central reason for interpreting findings and connecting them with evidence was the need to provide examples that could serve as potentially transferable findings for others using video with their research. Given the need for a fertile environment (Zhao & Frank, 2003 ) and attention to contextual differences to avoid lethal mutations (Brown & Campione, 1996 ), understand that these examples may not work for every situation, but the intent is to provide clear evidence of how video research methods can leverage storytelling to report research findings in a way that is consumable by a broader audience.

In the following section, we present findings from the review of research and practice, along with evidence from our work with video research, connecting the conceptual and operational frame to examples and teasing out aspects from existing literature.

Results and findings

When looking at the current literature regarding the use of video in research, we developed a Mind Map to categorize convergent and divergent themes in the current literature, see Fig. 1 . Although this is far from a complete meta-analysis on video research (notably absent is a comprehensive discussion of ethical concerns regarding video research), the Mind Map focuses on four main properties in regards to video: video as a tool for storytelling/research, properties of the camera/video itself, how video impacts the person/researcher, and methods by which the researcher/viewer consumes video.

Mind Map of current literature regarding the use of video in mixed methods research. Link to the fully interactive Mind Map- http://clemsongc.com/ebwalker/mindmap/

Video, when used as a tool for research, can document and share ethnographic, epistemic, and storytelling data to participants and to the research team (R. Goldman, 2007 ; Heath et al., 2010 ; Miller & Zhou, 2007 ; Tobin & Hsueh, 2007 ). Much of the research in this area focuses on the properties (both positive and negative) inherent in the camera itself such as how video footage can increase the ability to see and experience the world, but can also act as a selective lens that separates an event from its natural context (S. Goldman & McDermott, 2007 ; Jewitt, n.d .; Knoblauch & Tuma, 2011 ; MacDougall, 2011 ; Miller & Zhou, 2007 ; Roth, 2007 ; Sossi, 2013 ).

Some research speaks to the role of the video-researcher within the context of the study, likening a video researcher to a participant-observer in ethnographic research (Derry, 2007 ; Roth, 2007 ; Sossi, 2013 ). The final category of research within the Mind Map focuses on the process of converting the video from an observation to records to artifact to dataset to pattern (Barron, 2007 ; R. Goldman, 2007 ; Knoblauch & Tuma, 2011 ; Newbury, 2011 ). Through this process of conversion, the video footage itself becomes an integral part of both the data and findings.

The focus throughout current literature was on video as data and the role it plays in collection and analysis during a study, but little has been written about how video could be used as a vehicle to present findings of a study. Current literature also did not address whether video-data could be used as a tool to communicate the findings of the research to a broader audience.

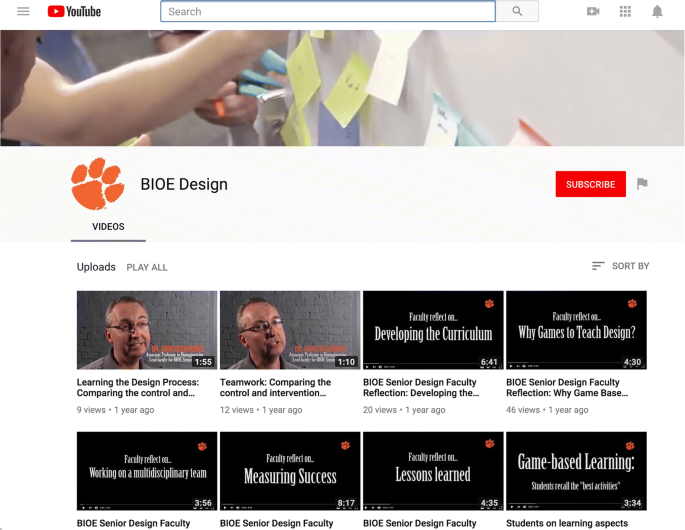

In a recent two-year study, the research team led by Dr. Erica Walker collected several types of video footage with the embedded intent to use video as both data and for telling the story of the study and findings once concluded (Walker, 2016 ). The study focused on a multidisciplinary team that converted a higher education Engineering course from lecture-based to game-based learning using the Cognitive Apprenticeship educational framework. The research questions examined the impact that the intervention had on student learning of domain content and twenty-first Century Skills. Utilizing video as both a data source and a delivery method was built into the methodology from the beginning. Therefore, interviews were conducted with the researchers and instructors before, during, and after the study to document consistency and changes in thoughts and observations as the study progressed. At the conclusion of the study, student participants reflected on their experience directly through individual video interviews. In addition, every class was documented using two static cameras, placed at different angles and framing, and a mobile camera unit to capture closeup shots of student-instructor, student-student, and student-content interactions. This resulted in more than six-hundred minutes of interview footage and over five-thousand minutes of classroom footage collected for the study.

Video data can be analyzed through quantitative methods (frequencies and word maps) as well as qualitative methods (emergent coding and commonalities versus outliers). Ideally, both methods are used in tandem so that preliminary results can continue to inform the overall analysis as it progresses. In order to capitalize on both methods, each interview was transcribed. The researchers leveraged digital and analog methods of coding such as digital word-search alongside hand coding the printed transcripts. Transcriptions contained timecode notations throughout, so coded segments could quickly be located in the footage and added to a timeline creating preliminary edits.

There are many software workflows that allow researchers to code, notate timecode for analysis, and pre-edit footage. In the study, Opportunities for Innovation: Game-based Learning in an Engineering Senior Design Course, NVivo qualitative analysis software was used together with paper-based analog coding. In a current study, also based on a higher education curriculum intervention, we are digitally coding and pre-trimming the footage in Adobe Prelude in addition to analog coding on the printed transcripts. Both workflows offer advantages. NVivo has built-in tools to create frequency maps and export graphs and charts relevant to qualitative analysis whereas Adobe Prelude adds coding notes directly into the footage metadata and connects directly with Adobe Premiere video editing software, which streamlines the editing process.

From our experience with both workflows, Prelude works better for a research team that has multiple team members with more video experience because it aligns with video industry workflows, implements tools that filmmakers already use, and Adobe Team Projects allows for co-editing and coding from multiple off-site locations. On the other hand, NVivo works better for research teams where members have more separate roles. NVivo is a common qualitative-analysis software so team members more familiar with traditional qualitative research can focus on coding and those more familiar with video editing can edit based on those codes allowing each team member to work within more familiar software workflows.

In both of these studies, assessments regarding storytelling occurred in conjunction with data processing and analysis. As findings were revealed, appropriate clips were grouped into timelines and edited to produce a library of short, topic-driven videos posted online , see Fig. 2 . A collection of story-based, topic-driven videos can provide other practitioners and researchers a first-hand account of how a study was designed and conducted, what worked well, recommendations of what to do differently, participant perspectives, study findings, and suggestions for further research. In fact, the videos cover many of the same topics traditionally found in publications, but in a collection of short videos accessible to a broad audience online.

The YouTube channel created for Opportunities for Innovation: Game-based Learning in an Engineering Senior Design Course containing twenty-four short topical videos. Direct link- https://goo.gl/p8CBGG

By sharing the results of the study publicly online, conversations between practitioners and researchers can develop on a public stage. Research videos are easy to share across social media channels which can broaden the academic audience and potentially open doors for future research collaborations. As more journals move to accept multi-media studies, publicly posted videos provide additional ways to expose both academics and the general public to important study results and create easy access to related resources.

Video research as storytelling: The intersection and divergence of documentary filmmaking and video research

“Film and writing are such different modes of communication, filmmaking is not just a way of communicating the same kinds of knowledge that can be conveyed by an anthropological text. It is a way of creating different knowledge” (MacDougall, 2011 ).

When presenting research, choosing either mode of communication comes with affordances and constraints for the researcher, the participants, and the potential audience.

Many elements of documentary filmmaking, but not all, are relevant and appropriate when applied to gathering data and presenting results in video research. Documentary filmmakers have a specific angle on a story that they want to share with a broad audience. In many cases, they hope to incite action in viewers as a response to the story that unfolds on screen. In order to further their message, documentarians carefully consider the camera shots and interview clips that will convey the story clearly in a similar way to filmmakers in narrative genres. Decisions regarding what to capture and how to use the footage happen throughout the entire filmmaking process: prior to shooting footage (pre-production), while capturing footage (production), and during the editing phase (post-production).

Video researchers can employ many of the same technical skills from documentary filmmaking including interview techniques such as pre-written questions; camera skills such as framing, exposure, and lighting; and editing techniques that help draw a viewer through the storyline (Erickson, 2007 ; Tobin & Hsueh, 2007 ). In both documentary filmmaking and in video research, informed decisions are made about what footage to capture and how to employ editing techniques to produce a compelling final video.

Where video research diverges from documentary filmmaking is in how the researcher thinks about, captures, and processes the footage. Video researchers collect video as data in a more exploratory way whereas documentary filmmakers often look to capture preconceived video that will enable them to tell a specific story. For a documentary filmmaker, certain shots and interview responses are immediately discarded as they do not fit the intended narrative. For video researchers, all the video that is captured throughout a study is data and potentially part of the final research narrative. It is during the editing process (post-production) where the distinction between data and narrative becomes clear.

During post-production, video researchers are looking for clips that clearly reflect the emergent storylines seen in the collective data pool rather than the footage necessary to tell a predetermined story. Emergent storylines can be identified in several ways. Researchers look for divergent statements (where an interview subject makes unique observation different from other interviewees), convergent statements (where many different interviewees respond similarly), and unexpected statements (where something different from what was expected is revealed) (Knoblauch & Tuma, 2011 ).

When used thoughtfully, video research provides many sources of rich data. Examples include reflections of the experience, in the direct words of participants, that contain insights provided by body language and tone, an immersive glimpse into the research world as it unfolds, and the potential to capture footage throughout the entire research process rather than just during prescribed times. Video research becomes especially powerful when combined with qualitative and quantitative data from other sources because it can help reveal the context surrounding insights discovered during analysis.

We are not suggesting that video researchers should become documentary filmmakers, but researchers can learn from the stylistic approaches employed in documentary filmmaking. Video researchers implementing these tools can leverage the strengths of short-format video as a storytelling device to share findings with a more diverse audience, increase audience understanding and consumption of findings, and encourage a broader conversation around the research findings.

Implications for future work

As the development of digital media technologies continues to progress, we can expect new functionalities far exceeding current tools. These advancements will continue to expand opportunities for creating and sharing stories through video. By considering the role of video from the first stages of designing a study, researchers can employ methods that capitalize on these emerging technologies. Although they are still rapidly advancing, researchers can look for ways that augmented reality and virtual reality could change data analysis and reporting of research findings. Another emergent area is the use of machine learning and artificial intelligence to rapidly process video footage based on automated thematic coding. Continued advancements in this area could enable researchers to quickly quantify data points in large quantities of footage.

In addition to exploring new functionalities, researchers can still use current tools more effectively for capturing data, supporting analysis, and reporting findings. Mobile devices provide ready access to collect periodic video reflections from study participants and even create research vlogs (video blogs) to document and share ongoing studies as they progress. In addition, participant-created videos are rich artifacts for evaluating technical and conceptual knowledge as well as affective responses. Most importantly, as a community, researchers, designers, and documentarians can continue to take strengths from each field to further the reach of important research findings into the public sphere.

In conclusion, current research is focused on using video as a tool for data collection and analysis, but there are new, emerging opportunities for video to play an increased and diversified role in mixed methods research, especially as a tool for the presentation and consumption of findings. By leveraging the storytelling techniques used in documentary filmmaking, while staying true to the analytical methods of research design, researchers can use video to effectively communicate implications of their work to an audience beyond academia and leverage video storytelling to disseminate findings to the public.

Bailey, P. H., & Tilley, S. (2002). Storytelling and the interpretation of meaning in qualitative research. J Adv Nurs, 38(6), 574–583. http://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.02224.x

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. W. (2012). Arts based research (pp. 1–183). https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230627

Barron B (2007) Video as a tool to advance understanding of learning and development in peer, family, and other informal learning contexts. Video Research in the Learning Sciences:159–187

Brown AL, Campione JC (1996) Psychological theory and the design of innovative learning environments: on procedures, principles and systems. In: Schauble L, Glaser R (eds) Innovations in learning: new environments for education. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ, pp 234–265

Google Scholar

Chalfen, R. (2011). Looking Two Ways: Mapping the Social Scientific Study of Visual Culture. In E. Margolis & L. Pauwels (Eds.), The Sage handbook of visual research methods . books.google.com

Chattoo, C. B., & Das, A. (2014). Assessing the Social Impact of Issues-Focused Documentaries: Research Methods and Future Considerations Center for Media & Social Impact, 24. Retrieved from https://www.namac.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/01/assessing_impact_social_issue_documentaries_cmsi.pdf

Collins, A., Joseph, D., & Bielaczyc, K. (2004). Design research: theoretical and methodological issues. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 15–42. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1301_2

Dahlstrom, M. F. (2014). Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 111(Supplement_4), 13614–13620. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320645111

de Carteret, P. (2008). Storytelling as research praxis, and conversations that enabled it to emerge. Int J Qual Stud Educ, 21(3), 235–249. http://doi.org/10.1080/09518390801998296

de Jager A, Fogarty A, Tewson A (2017) Digital storytelling in research: a systematic review. Qual Rep 22(10):2548–2582

Derry SJ (2007) Video research in classroom and teacher learning (Standardize that!). Video Research in the Learning Sciences:305–320

Erickson F (2007) Ways of seeing video: toward a phenomenology of viewing minimally edited footage. Video Research in the Learning Sciences:145–155

Gallagher, K. M. (2011). In search of a theoretical basis for storytelling in education research: story as method. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 34(1), 49–61. http://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2011.552308

Gliner, J. A., Morgan, G. A., & Leech, N. L. (2009). Research Methods in Applied Settings: An Integrated Approach to Design and Analysis, Second Edition . Taylor & Francis

Goldman R (2007) Video representations and the perspectivity framework: epistemology, ethnography, evaluation, and ethics. Video Research in the Learning Sciences 37:3–37

Goldman S, McDermott R (2007) Staying the course with video analysis Video Research in the Learning Sciences:101–113

Hancox, D. (2017). From subject to collaborator: transmedia storytelling and social research. Convergence, 23(1), 49–60. http://doi.org/10.1177/1354856516675252

Heath, C., Hindmarsh, J., & Luff, P.(2010). Video in Qualitative Research. SAGE Publications. Retrieved from https://market.android.com/details?id=book-MtmViguNi4UC

Heider KG (2009) Ethnographic film: revised edition. University of Texas Press

Henley P (2010) The Adventure of the Real: Jean Rouch and the Craft of Ethnographic Cinema. University of Chicago Press

Jewitt, C. (n.d). An introduction to using video for research - NCRM EPrints Repository. National Centre for Research Methods. Institute for Education, London. Retrieved from http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2259/4/NCRM_workingpaper_0312.pdf

Knoblauch H, Tuma R (2011) Videography: An interpretative approach to video-recorded micro-social interaction. The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods :414–430

Koehler D (2012) Documentary and ethnography: exploring ethical fieldwork models. Elon Journal Undergraduate Research in Communications 3(1):53–59 Retrieved from https://www.elon.edu/docs/e-web/academics/communications/research/vol3no1/EJSpring12_Full.pdf#page=53i

Lawrence-Lightfoot, S. (2005). Reflections on portraiture: a dialogue between art and science. Qualitative Inquiry: QI, 11(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800404270955

LeBaron, C., Jarzabkowski, P., Pratt, M. G., & Fetzer, G. (2017). An introduction to video methods in organizational research. Organ Res Methods, 21(2), 109442811774564. http://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117745649

Lenette, C., Cox, L., & Brough, M. (2013). Digital storytelling as a social work tool: learning from ethnographic research with women from refugee backgrounds. Br J Soc Work, 45(3), 988–1005. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct184

Lewis, P. J. (2011). Storytelling as research/research as storytelling. Qual Inq, 17(6), 505–510. http://doi.org/10.1177/1077800411409883

(2011) Anthropological filmmaking: An empirical art. In: The sage handbook of visual research methods. MacDougall, D, pp 99–113

Meadows D (2003) Digital storytelling: research-based practice in new media. Visual Com(2):189–193

Miller K, Zhou X (2007) Learning from classroom video: what makes it compelling and what makes it hard. Video Research in the Learning Sciences:321–334

Newbury, D. (2011). Making arguments with images: Visual scholarship and academic publishing. In Eric Margolis & (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods . na

Nichols B (2010) Why are ethical issues central to documentary filmmaking? Introduction to Documentary , Second Edition . In: 42–66

Roth W-M (2007) Epistemic mediation: video data as filters for the objectification of teaching by teachers. In: Goldman R, Pea R, Barron B, Derry SJ (eds) Video research in the learning sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Ass Mahwah, NJ, pp 367–382

Sossi, D. (2013). Digital Icarus? Academic Knowledge Construction and Multimodal Curriculum Development, 339

Tobin J, Hsueh Y (2007) The poetics and pleasures of video ethnography of education. Video Research in the Learning Sciences:77–92

Using Film in Ethnographic Field Research - Methods@Manchester - The University of Manchester. (n.d.). Retrieved March 12, 2018, from https://www.methods.manchester.ac.uk/themes/ethnographic-methods/ethnographic-field-research/

Walker, E. B. (2016). Opportunities for Innovation: Game-based Learning in an Engineering Senior Design Course (PhD). Clemson University. Retrieved from http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1805/

Warmington, P., van Gorp, A., & Grosvenor, I. (2011). Education in motion: uses of documentary film in educational research. Paedagog Hist, 47(4), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230.2011.588239

Zhao, Y., & Frank, K. A. (2003). Factors affecting technology uses in schools: an ecological perspective. Am Educ Res J , 40(4), 807–840. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312040004807

Download references

There was no external or internal funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available in the Mind Map online which visually combines and interprets the full reference section available at the end of the full document.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Graphic Communication, Clemson University, 207 Godfrey Hall, Clemson, SC, 29634, USA

Erica B. Walker

College of Education, Clemson University, 207 Tillman Hall, Clemson, SC, 29634, USA

D. Matthew Boyer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions