Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

Health Conditions

- Breast Cancer

- Cancer Care

- Caregiving for Alzheimer's Disease

- Chronic Kidney Disease

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

- Digestive Health

- Heart Health

- Mental Health

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

- Sleep Health

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Weight Management

Condition Spotlight

Wellness Topics

- Mental Well-Being

- Sexual Health

- Vitamins and Supplements

- Women's Wellness

Product Reviews

- At-Home Testing

- Men's Health

- Women's Health

Featured Programs

- Video Series

- Pill Identifier

- Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Essentials

- Diabetes Nutrition

- High Cholesterol

- Taming Inflammation in Psoriasis

- Taming Inflammation in Psoriatic Arthritis

Newsletters

- Anxiety and Depression

- Nutrition Edition

- Wellness Wire

Lifestyle Quizzes

- Find a Diet

- Find Healthy Snacks

- How Well Do You Sleep?

- Are You a Workaholic?

Find Your Bezzy Community

Bezzy communities provide meaningful connections with others living with chronic conditions. Join Bezzy on the web or mobile app.

Follow us on social media

Can't get enough? Connect with us for all things health.

Health News

Is too much homework bad for kids’ health.

Research shows that some students regularly receive higher amounts of homework than experts recommend, which may cause stress and negative health effects.

Research suggests that when students are pushed to handle a workload that’s out of sync with their development level, it can lead to significant stress — for children and their parents.

Both the National Education Association (NEA) and the National PTA (NPTA) support a standard of “10 minutes of homework per grade level” and setting a general limit on after-school studying.

For kids in first grade, that means 10 minutes a night, while high school seniors could get two hours of work per night.

Experts say there may be real downsides for young kids who are pushed to do more homework than the “10 minutes per grade” standard.

“The data shows that homework over this level is not only not beneficial to children’s grades or GPA, but there’s really a plethora of evidence that it’s detrimental to their attitude about school, their grades, their self-confidence, their social skills, and their quality of life,” Donaldson-Pressman told CNN .

But the most recent study to examine the issue found that kids in their study who were in early elementary school received about three times the amount of recommended homework.

Published in The American Journal of Family Therapy, the 2015 study surveyed more than 1,100 parents in Rhode Island with school-age children.

The researchers found that first and second graders received 28 and 29 minutes of homework per night.

Kindergarteners received 25 minutes of homework per night, on average. But according to the standards set by the NEA and NPTA, they shouldn’t receive any at all.

A contributing editor of the study, Stephanie Donaldson-Pressman, told CNN that she found it “absolutely shocking” to learn that kindergarteners had that much homework.

And all those extra assignments may lead to family stress, especially when parents with limited education aren’t confident in their ability to talk with the school about their child’s work.

The researchers reported that family fights about homework were 200 percent more likely when parents didn’t have a college degree.

Some parents, in fact, have decided to opt out of the whole thing. The Washington Post reported in 2016 that some parents have just instructed their younger children not to do their homework assignments.

They report the no-homework policy has taken the stress out of their afternoons and evenings. In addition, it’s been easier for their children to participate in after-school activities.

Consequences for high school students

Other studies have found that high school students may also be overburdened with homework — so much that it’s taking a toll on their health.

In 2013, research conducted at Stanford University found that students in high-achieving communities who spend too much time on homework experience more stress, physical health problems, a lack of balance in their lives, and alienation from society.

That study, published in The Journal of Experimental Education , suggested that any more than two hours of homework per night is counterproductive.

However, students who participated in the study reported doing slightly more than three hours of homework each night, on average.

To conduct the study, researchers surveyed more than 4,300 students at 10 high-performing high schools in upper middle-class California communities. They also interviewed students about their views on homework.

When it came to stress, more than 70 percent of students said they were “often or always stressed over schoolwork,” with 56 percent listing homework as a primary stressor. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

The researchers asked students whether they experienced physical symptoms of stress, such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss, and stomach problems.

More than 80 percent of students reported having at least one stress-related symptom in the past month, and 44 percent said they had experienced three or more symptoms.

The researchers also found that spending too much time on homework meant that students were not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills. Students were more likely to forgo activities, stop seeing friends or family, and not participate in hobbies.

Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” said Denise Pope, PhD, a senior lecturer at the Stanford University School of Education, and a co-author of a study.

Pressure to work as hard as adults takes a toll

A smaller New York University study published in 2015 noted similar findings.

It focused more broadly on how students at elite private high schools cope with the combined pressures of school work, college applications, extracurricular activities, and parents’ expectations.

That study, which appeared in Frontiers in Psychology, noted serious health effects for high schoolers, such as chronic stress, emotional exhaustion, and alcohol and drug use.

The research involved a series of interviews with students, teachers, and administrators, as well as a survey of a total of 128 juniors from two private high schools.

About half of the students said they received at least three hours of homework per night. They also faced pressure to take college-level classes and excel in activities outside of school.

Many students felt they were being asked to work as hard as adults, and noted that their workload seemed inappropriate for their development level. They reported having little time for relaxing or creative activities.

More than two-thirds of students said they used alcohol and drugs, primarily marijuana, to cope with stress.

The researchers expressed concern that students at high-pressure high schools can get burned out before they even get to college.

“School, homework, extracurricular activities, sleep, repeat — that’s what it can be for some of these students,” said Noelle Leonard, PhD, a senior research scientist at the New York University College of Nursing, and lead study author, in a press release .

The quality of homework assignments matters more than quantity

Experts continue to debate the benefits and drawbacks of homework.

But according to an article published this year in Monitor on Psychology , there’s one thing they agree on: the quality of homework assignments matters.

In the Stanford study, many students said that they often did homework they saw as “pointless” or “mindless.”

Pope, who co-authored that study, argued that homework assignments should have a purpose and benefit, and should be designed to cultivate learning and development.

It’s also important for schools and teachers to stick to the 10-minutes per grade standard.

In an interview with Monitor on Psychology, Pope pointed out that students can learn challenging skills even when less homework is assigned.

Pope described one teacher she worked with who taught Advanced Placement biology, and experimented by dramatically cutting down homework assignments. First the teacher cut homework by a third, and then cut the assignments in half.

The students’ test scores didn’t change.

“You can have a rigorous course and not have a crazy homework load,” Pope said.

Editor’s Note: The story was originally reported by Sandra Levy on April 11, 2017. Its current publication date reflects an update, which includes a medical review by Karen Gill, MD .

Share this article

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Don't Forget to Enter Today's Very Merry Giveaway!🎁

Should Homework Be Banned? Here’s What Real Educators Think

Plus, what research on the subject really tells us.

Every kid dreams of it: “Homework banned forevermore!” For as long as anyone can remember, homework has just been one of those things kids have to do because it’s good for them, like eating their vegetables. But is it really as important to do hours of homework every night as it is to eat broccoli and carrots? New research suggests homework might not have a whole lot of value. This leads to a big question: Should we ban homework?

“I think parents already have enough stress just in providing for their families!” says one Arizona 1st grade teacher. “I can imagine one more chore of having to sit down and do homework with their child would add that much more stress. Kids don’t like doing homework, so it frustrates them, which in turn frustrates parents. They spend time fighting about homework that they could be spending quality time over a board game or family meal!”

We wanted to know more, as every educator should. So, we combed through recent research to see what experts say, and explored the news to see what schools in the United States and abroad have tried. Plus, we asked 40+ active K-12 educators to share their thoughts. Here’s what we found out.

Does homework actually work?

This is one of the biggest questions people have around homework bans. Is it worth the time students are spending on it? How many kids actually do it consistently? How involved do parents need to be? In short: Does homework have value?

What the Research Says

Educators first started asking serious questions about homework more than 20 years ago, when an article that evaluated decades of research on homework suggested that it might not be as effective as we thought, at least in the lower grades . But other studies on homework indicate that students who do homework as assigned have higher academic outcomes overall, especially in grades 7 through 12.

What Real Educators Say

Most of the teachers that responded to our survey felt homework (especially for upper grades) does have at least some value. Many, though, were less concerned with academic benefits and more with developing general life skills like time management and responsibility.

- “For older students, reasonable homework that is preparation for class the next day helps students learn how to manage their time, meet deadlines, and take responsibility for their learning. I am a fan of flipped learning—students watch the lesson for homework and then use class time to ask questions, work together, work with their teacher, and do the work.” —Julie Mason, MS/HS English teacher

- “In middle school and high school, homework is important because it helps build stamina and potential study habits for college or trade schools.” —Desiree T., elementary teacher

- “Homework is good practice for subjects like math. In other subjects, it is good for reviewing subject matter.” —Ohio 8th grade social studies teacher

- “The proper amount of homework that is relevant to the daily lessons will help reinforce the skill and allow parents to see what their child is learning.” —Joanie B., Texas 4th/6th grade teacher

- “It’s not beneficial; parents today have not been taught how to help with new strategies. They are also often so busy that they cannot be bothered to help so they just give the answers. I saw a lot of this during the pandemic and even after when I would have 1st graders tell me they knew the answer ‘because they just know it.’ Not to mention the students who would actually benefit from having the extra practice of homework oftentimes do not have the support at home.” —Georgia 3rd grade teacher

- “In my 8 years of teaching, homework has never been successful for families or me. For the majority of parents and kids, it’s overwhelming. It is also additional work for teachers to manage. This is another extension and overreach of the expectations of the teacher.” —Lauren Anderson, Ohio 4th grade teacher

- “Homework isn’t busy work. How will today’s youth become tomorrow’s leaders (or survive college/trades classes) if they aren’t practicing skills to the next level?” —Arizona 1st grade teacher

Should we ban homework in elementary school?

Most adults today didn’t have homework in kindergarten, so they’re surprised when their child arrives home with a backpack full of worksheets. Older elementary students frequently bring home big projects like making a diorama or creating a family tree, something that usually means a lot of parent involvement. Is homework at this age reasonable and meaningful?

Supporters of a homework ban often cite research from John Hattie, who concluded that elementary school homework has no effect on academic progress. In a podcast he said, “Homework in primary school has an effect of around zero … It’s one of those lower hanging fruits that we should be looking in our primary schools to say, ‘Is it really making a difference?’”

The general wisdom these days seems to point to less homework overall at the elementary level, with one huge exception: reading. The research agrees: kids need to read at home as well as at school. Most educators recommend kids spend at least 20 minutes reading at home every single day.

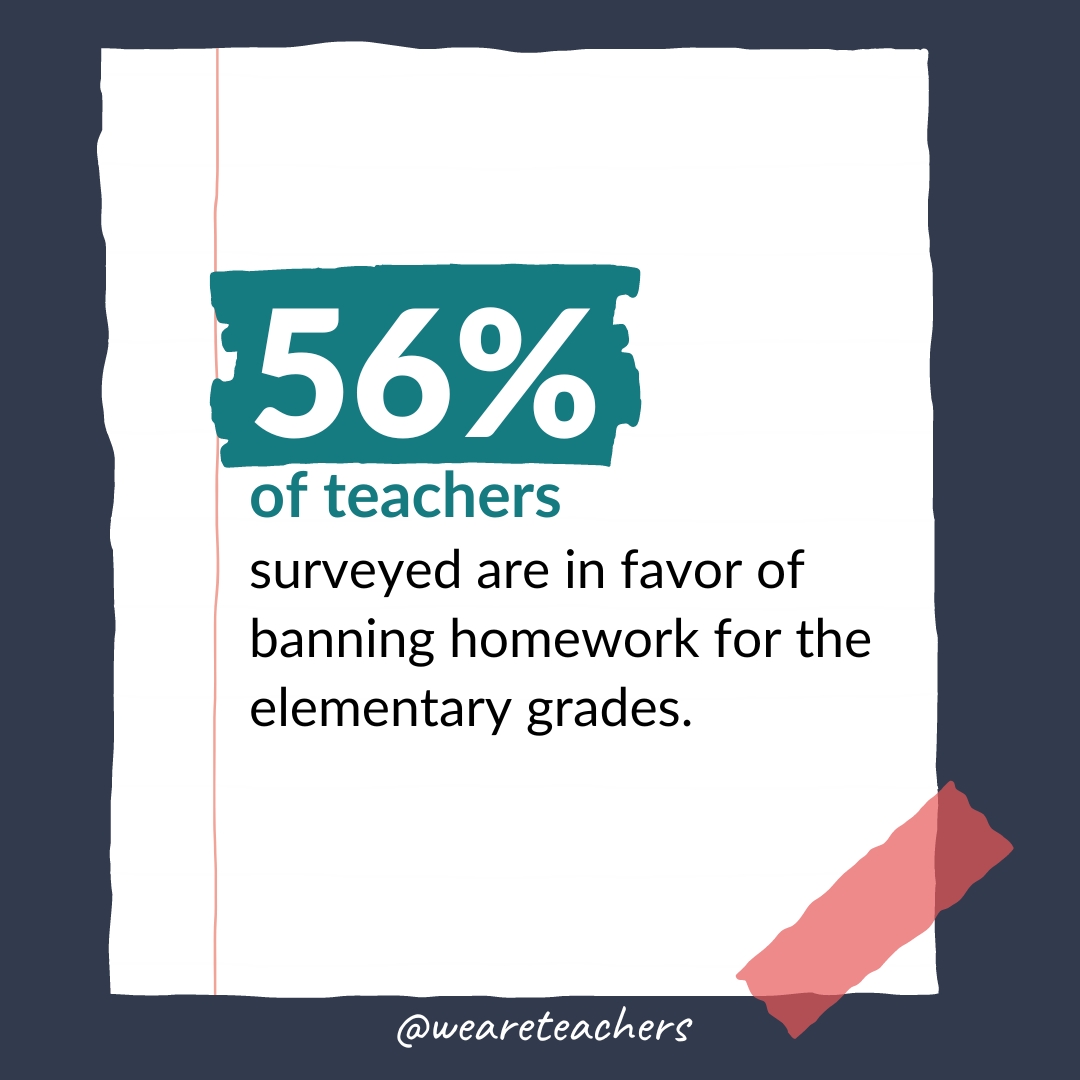

More than half of our survey respondents (56%) are in favor of banning homework for the elementary grades. They worried about kids not having support or resources at home and taking away their time for creative play or family activities. But some teachers still find value in elementary homework, especially for math and reading, as long as it’s minimal. ADVERTISEMENT

- “The common push for homework in elementary schools is ‘to prepare them for high school.’ That’s overreach. The elementary child’s job is to be an elementary child. We need to teach children where they are.” —Lauren Anderson

- “In elementary school, there should be a mixture of homework and unhomework activities. For example, a homework menu with a list of activities to complete for the month or for the week: Read in pajamas for 20 minutes, complete 3 math sheets, help cook dinner, have a family movie night, write your first and last name 10 times, help pack your snack, etc.” —Desiree T.

- “No homework should be part of the teacher motto—work smarter, not harder. Teachers spend too much time grading homework. I believe teachers and students should commit to making every minute count in the classroom so everyone can go home and just be with family.” —Jennifer N., 5th grade teacher

- “Students are learning new concepts. There is not a guarantee that someone will be able to help them with these tasks. Practicing incorrectly is worse than no practice at all.” —High school resource specialist

- “Kids should be encouraged to read [at home] and spend time with families and friends.” —Elementary English language development teacher

How much homework is enough (or too much)?

If we agree that that answer to “should we ban homework altogether” is “no,” then how much homework is reasonable? The answer seems to vary by grade level, as you would expect. But many point out the need to focus on the quality of homework over the quantity. And there have been increasing calls to let kids enjoy their longer school breaks without homework hanging over their heads .

A 2019 study showed that teenagers have doubled the amount of time they spend on homework since the 1990s. This study found that teens spend about an hour a day doing homework on average, which many would argue isn’t unreasonable. But in another study , kids self-reported doing an average of three hours of homework a night, which seems a lot more significant.

The National PTA and the NEA recommend kids do about 10 minutes of homework per night per grade level. In other words, a 3rd grader should do 30 minutes of homework. A 12th grader would do 120 minutes, or two full hours.

Perhaps more important than “How much homework?” is “What kind of homework?” Meaningful practice of what kids learned in class that day can be helpful. Busywork is not. And assigning really difficult work for kids to tackle at home, without any help from a teacher or other expert voice, is likely to simply frustrate them. Unfortunately, most teachers don’t receive training on how to assign homework that is meaningful and relevant to students. This is another area where we really need to consider a major culture shift.

While 75% of those surveyed say homework has some value in the upper grades at least, most feel it shouldn’t be excessive. Teachers stressed that it should never be used as punishment. Plus, it’s important to remember not all kids have the same access to help and resources outside the classroom.

- “Homework is important but I also believe it shouldn’t exceed 30-60 minutes a night.” —Desiree T.

- “I do think elementary students should practice their reading and maybe 10 minutes of math [at home]. That may look different for each child due to how long it may take them to complete something.” —Wisconsin elementary special education teacher

- “Elementary students are not too young to have homework once or twice a week. More than that would be too much.” —Tanya T., HS ELA teacher

- “In order to prepare students for high school, I feel 20-30 minutes of homework is okay [in elementary school].” —Florida 5th grade teacher

- “A ton of homework in every subject is ridiculous. But having to read parts of a book or an article and do several math problems should not be burdensome. And the benefit of those two things has been documented.” —Teresa Rennie, Pennsylvania 8th grade teacher

- “I encourage my elementary students to read a little every day to develop a love of reading.” —Meenal Parikh, Ohio 1st grade teacher

- “I think some homework is reasonable. Should it be a hindrance to other other activities or a major inconvenience? No. Some is good, but it doesn’t need to be an every-night thing.” —Patrick Danz, Michigan high school ELA teacher

Are there benefits to less (or no) homework?

Some schools have already banned homework, both in the United States and around the world. In April 2024, Poland enacted a homework ban for students in grades 1 through 3. In grades 4 through 8, homework must be optional and can’t count toward a student’s grade. Finnish schools are famous for assigning less homework at all ages , yet continuing to score highly in international rankings. So what are the benefits of freeing kids from homework?

Prioritizing mental health is at the forefront of the homework ban movement. Leaders say they want to give students time to develop other hobbies, relationships, and balance in their lives. When two Utah elementary schools officially banned homework , they found psychologist referrals for anxiety decreased by more than 50%.

In some cases, less or no homework can even have a positive effect on academic outcomes. One high school math teacher dramatically reduced the number of practice problems he asked his students to tackle at home. He also decreased the impact of homework on grades (from 25% to 1%). Now kids had more time to spend on just a few practice problems, and they weren’t stressed about getting them wrong. The result of changes like these? Higher standardized test scores on average.

Some schools have experimented with extending the school day in exchange for eliminating homework. This ensures that kids have more time to do independent work while also ensuring access to expert assistance. After all, not all parents have the time or ability to help with homework. And Internet access isn’t a given in every household. Keeping schoolwork at school means giving all kids equal access to the resources they need.

Teachers worry that kids who spend too much time doing homework are losing out in other areas. They want younger students to have more time to play. Older kids should be able to decompress after spending hours in the classroom. And everyone deserves more opportunities for family time and extracurriculars.

- “The stress and time surrounding homework is unnecessary. Jobs don’t require you take work home so school shouldn’t either. If a kid needs to work more, school could reach out with extra help, but homework is a waste of time. Home is for family time.” —Stephanie G., Maryland 1st grade teacher

- “Homework creates an equity problem. Not all learners have access to the same environment or supports at home as they do in school. The students who have supportive parents and resources (tutors, etc.) will succeed, while others will be penalized.” —Illinois high school teacher

- “If they work at school, they don’t need to work at home. We’re teaching them that it’s okay for someone to tell them how to spend their off-time. School is their job. I don’t like working for free; why should they think that it’s okay?” —North Carolina 1st grade teacher

- “After-school programs, sports, and unstructured play is MUCH more meaningful and impactful for these generations of students.” —Lauren Anderson

- “There are other ways to teach children responsibility and time management than completing homework that will most likely be ungraded.” —4th grade social studies teacher

One Teacher’s Take on the Value of Homework: More Cons Than Pros

One 4th grade social studies teacher from North Carolina shared their thoughts with us in detail. We felt they were worth sharing with a wider audience. (Note: We’ve edited and condensed their words for space and clarity.)

Homework Hurts Families

“There are multiple factors that work together that make homework detrimental to students and their families. Children need to spend time with their parents building relationships of trust and respect. It is difficult because during the limited time families have together, they are forced by the schools to give that up to deal with homework.

“Many parents are unable to answer homework questions to help their children as methodology has changed and evolved. Homework becomes a stressful battlefield. Children with ADHD, autism, and other challenges have such a difficult time keeping focus at school. When they have to do additional work at home, there are increased meltdowns and battles, putting further strains on families.”

Homework’s Time Cost

“Children also have less time to complete work at home due to how overscheduled families have become. Children as young as 3rd grade arrive home from their games as late as 10:00 at night. That is often their first opportunity to sit down to complete their work. When they come to school the next day, they become irritable, unfocused, frustrated, and unable to quickly grasp new material.

“In older grades, teachers don’t plan together and don’t understand how much is required of the student to complete each night. If a high school student has six classes and each teacher assigns only 30 minutes of homework each night, that adds up to three hours. I hear of many teachers that each give an hour each night. I don’t see how it is possible for a high school student to complete six hours of homework every night.

“The additional stress of homework for the teacher, students, and families is not worth it. Give families time to spend together, and free up teacher time by not having to hunt down missing work and reviewing what they are not grading. Allow children to have a better bedtime and avoid meltdowns at home, which lead to additional stress, anxiety, and depression.”

We’d love to hear your thoughts—should homework be banned? Join the discussion in the We Are Teachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

You Might Also Like

150 Debate Topics for Middle School Students

Teach students to make effective arguments. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Are You Down With or Done With Homework?

- Posted January 17, 2012

- By Lory Hough

The debate over how much schoolwork students should be doing at home has flared again, with one side saying it's too much, the other side saying in our competitive world, it's just not enough.

It was a move that doesn't happen very often in American public schools: The principal got rid of homework.

This past September, Stephanie Brant, principal of Gaithersburg Elementary School in Gaithersburg, Md., decided that instead of teachers sending kids home with math worksheets and spelling flash cards, students would instead go home and read. Every day for 30 minutes, more if they had time or the inclination, with parents or on their own.

"I knew this would be a big shift for my community," she says. But she also strongly believed it was a necessary one. Twenty-first-century learners, especially those in elementary school, need to think critically and understand their own learning — not spend night after night doing rote homework drills.

Brant's move may not be common, but she isn't alone in her questioning. The value of doing schoolwork at home has gone in and out of fashion in the United States among educators, policymakers, the media, and, more recently, parents. As far back as the late 1800s, with the rise of the Progressive Era, doctors such as Joseph Mayer Rice began pushing for a limit on what he called "mechanical homework," saying it caused childhood nervous conditions and eyestrain. Around that time, the then-influential Ladies Home Journal began publishing a series of anti-homework articles, stating that five hours of brain work a day was "the most we should ask of our children," and that homework was an intrusion on family life. In response, states like California passed laws abolishing homework for students under a certain age.

But, as is often the case with education, the tide eventually turned. After the Russians launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, a space race emerged, and, writes Brian Gill in the journal Theory Into Practice, "The homework problem was reconceived as part of a national crisis; the U.S. was losing the Cold War because Russian children were smarter." Many earlier laws limiting homework were abolished, and the longterm trend toward less homework came to an end.

The debate re-emerged a decade later when parents of the late '60s and '70s argued that children should be free to play and explore — similar anti-homework wellness arguments echoed nearly a century earlier. By the early-1980s, however, the pendulum swung again with the publication of A Nation at Risk , which blamed poor education for a "rising tide of mediocrity." Students needed to work harder, the report said, and one way to do this was more homework.

For the most part, this pro-homework sentiment is still going strong today, in part because of mandatory testing and continued economic concerns about the nation's competitiveness. Many believe that today's students are falling behind their peers in places like Korea and Finland and are paying more attention to Angry Birds than to ancient Babylonia.

But there are also a growing number of Stephanie Brants out there, educators and parents who believe that students are stressed and missing out on valuable family time. Students, they say, particularly younger students who have seen a rise in the amount of take-home work and already put in a six- to nine-hour "work" day, need less, not more homework.

Who is right? Are students not working hard enough or is homework not working for them? Here's where the story gets a little tricky: It depends on whom you ask and what research you're looking at. As Cathy Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework , points out, "Homework has generated enough research so that a study can be found to support almost any position, as long as conflicting studies are ignored." Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth and a strong believer in eliminating all homework, writes that, "The fact that there isn't anything close to unanimity among experts belies the widespread assumption that homework helps." At best, he says, homework shows only an association, not a causal relationship, with academic achievement. In other words, it's hard to tease out how homework is really affecting test scores and grades. Did one teacher give better homework than another? Was one teacher more effective in the classroom? Do certain students test better or just try harder?

"It is difficult to separate where the effect of classroom teaching ends," Vatterott writes, "and the effect of homework begins."

Putting research aside, however, much of the current debate over homework is focused less on how homework affects academic achievement and more on time. Parents in particular have been saying that the amount of time children spend in school, especially with afterschool programs, combined with the amount of homework given — as early as kindergarten — is leaving students with little time to run around, eat dinner with their families, or even get enough sleep.

Certainly, for some parents, homework is a way to stay connected to their children's learning. But for others, homework creates a tug-of-war between parents and children, says Liz Goodenough, M.A.T.'71, creator of a documentary called Where Do the Children Play?

"Ideally homework should be about taking something home, spending a few curious and interesting moments in which children might engage with parents, and then getting that project back to school — an organizational triumph," she says. "A nag-free activity could engage family time: Ask a parent about his or her own childhood. Interview siblings."

Instead, as the authors of The Case Against Homework write, "Homework overload is turning many of us into the types of parents we never wanted to be: nags, bribers, and taskmasters."

Leslie Butchko saw it happen a few years ago when her son started sixth grade in the Santa Monica-Malibu (Calif.) United School District. She remembers him getting two to four hours of homework a night, plus weekend and vacation projects. He was overwhelmed and struggled to finish assignments, especially on nights when he also had an extracurricular activity.

"Ultimately, we felt compelled to have Bobby quit karate — he's a black belt — to allow more time for homework," she says. And then, with all of their attention focused on Bobby's homework, she and her husband started sending their youngest to his room so that Bobby could focus. "One day, my younger son gave us 15-minute coupons as a present for us to use to send him to play in the back room. … It was then that we realized there had to be something wrong with the amount of homework we were facing."

Butchko joined forces with another mother who was having similar struggles and ultimately helped get the homework policy in her district changed, limiting homework on weekends and holidays, setting time guidelines for daily homework, and broadening the definition of homework to include projects and studying for tests. As she told the school board at one meeting when the policy was first being discussed, "In closing, I just want to say that I had more free time at Harvard Law School than my son has in middle school, and that is not in the best interests of our children."

One barrier that Butchko had to overcome initially was convincing many teachers and parents that more homework doesn't necessarily equal rigor.

"Most of the parents that were against the homework policy felt that students need a large quantity of homework to prepare them for the rigorous AP classes in high school and to get them into Harvard," she says.

Stephanie Conklin, Ed.M.'06, sees this at Another Course to College, the Boston pilot school where she teaches math. "When a student is not completing [his or her] homework, parents usually are frustrated by this and agree with me that homework is an important part of their child's learning," she says.

As Timothy Jarman, Ed.M.'10, a ninth-grade English teacher at Eugene Ashley High School in Wilmington, N.C., says, "Parents think it is strange when their children are not assigned a substantial amount of homework."

That's because, writes Vatterott, in her chapter, "The Cult(ure) of Homework," the concept of homework "has become so engrained in U.S. culture that the word homework is part of the common vernacular."

These days, nightly homework is a given in American schools, writes Kohn.

"Homework isn't limited to those occasions when it seems appropriate and important. Most teachers and administrators aren't saying, 'It may be useful to do this particular project at home,'" he writes. "Rather, the point of departure seems to be, 'We've decided ahead of time that children will have to do something every night (or several times a week). … This commitment to the idea of homework in the abstract is accepted by the overwhelming majority of schools — public and private, elementary and secondary."

Brant had to confront this when she cut homework at Gaithersburg Elementary.

"A lot of my parents have this idea that homework is part of life. This is what I had to do when I was young," she says, and so, too, will our kids. "So I had to shift their thinking." She did this slowly, first by asking her teachers last year to really think about what they were sending home. And this year, in addition to forming a parent advisory group around the issue, she also holds events to answer questions.

Still, not everyone is convinced that homework as a given is a bad thing. "Any pursuit of excellence, be it in sports, the arts, or academics, requires hard work. That our culture finds it okay for kids to spend hours a day in a sport but not equal time on academics is part of the problem," wrote one pro-homework parent on the blog for the documentary Race to Nowhere , which looks at the stress American students are under. "Homework has always been an issue for parents and children. It is now and it was 20 years ago. I think when people decide to have children that it is their responsibility to educate them," wrote another.

And part of educating them, some believe, is helping them develop skills they will eventually need in adulthood. "Homework can help students develop study skills that will be of value even after they leave school," reads a publication on the U.S. Department of Education website called Homework Tips for Parents. "It can teach them that learning takes place anywhere, not just in the classroom. … It can foster positive character traits such as independence and responsibility. Homework can teach children how to manage time."

Annie Brown, Ed.M.'01, feels this is particularly critical at less affluent schools like the ones she has worked at in Boston, Cambridge, Mass., and Los Angeles as a literacy coach.

"It feels important that my students do homework because they will ultimately be competing for college placement and jobs with students who have done homework and have developed a work ethic," she says. "Also it will get them ready for independently taking responsibility for their learning, which will need to happen for them to go to college."

The problem with this thinking, writes Vatterott, is that homework becomes a way to practice being a worker.

"Which begs the question," she writes. "Is our job as educators to produce learners or workers?"

Slate magazine editor Emily Bazelon, in a piece about homework, says this makes no sense for younger kids.

"Why should we think that practicing homework in first grade will make you better at doing it in middle school?" she writes. "Doesn't the opposite seem equally plausible: that it's counterproductive to ask children to sit down and work at night before they're developmentally ready because you'll just make them tired and cross?"

Kohn writes in the American School Board Journal that this "premature exposure" to practices like homework (and sit-and-listen lessons and tests) "are clearly a bad match for younger children and of questionable value at any age." He calls it BGUTI: Better Get Used to It. "The logic here is that we have to prepare you for the bad things that are going to be done to you later … by doing them to you now."

According to a recent University of Michigan study, daily homework for six- to eight-year-olds increased on average from about 8 minutes in 1981 to 22 minutes in 2003. A review of research by Duke University Professor Harris Cooper found that for elementary school students, "the average correlation between time spent on homework and achievement … hovered around zero."

So should homework be eliminated? Of course not, say many Ed School graduates who are teaching. Not only would students not have time for essays and long projects, but also teachers would not be able to get all students to grade level or to cover critical material, says Brett Pangburn, Ed.M.'06, a sixth-grade English teacher at Excel Academy Charter School in Boston. Still, he says, homework has to be relevant.

"Kids need to practice the skills being taught in class, especially where, like the kids I teach at Excel, they are behind and need to catch up," he says. "Our results at Excel have demonstrated that kids can catch up and view themselves as in control of their academic futures, but this requires hard work, and homework is a part of it."

Ed School Professor Howard Gardner basically agrees.

"America and Americans lurch between too little homework in many of our schools to an excess of homework in our most competitive environments — Li'l Abner vs. Tiger Mother," he says. "Neither approach makes sense. Homework should build on what happens in class, consolidating skills and helping students to answer new questions."

So how can schools come to a happy medium, a way that allows teachers to cover everything they need while not overwhelming students? Conklin says she often gives online math assignments that act as labs and students have two or three days to complete them, including some in-class time. Students at Pangburn's school have a 50-minute silent period during regular school hours where homework can be started, and where teachers pull individual or small groups of students aside for tutoring, often on that night's homework. Afterschool homework clubs can help.

Some schools and districts have adapted time limits rather than nix homework completely, with the 10-minute per grade rule being the standard — 10 minutes a night for first-graders, 30 minutes for third-graders, and so on. (This remedy, however, is often met with mixed results since not all students work at the same pace.) Other schools offer an extended day that allows teachers to cover more material in school, in turn requiring fewer take-home assignments. And for others, like Stephanie Brant's elementary school in Maryland, more reading with a few targeted project assignments has been the answer.

"The routine of reading is so much more important than the routine of homework," she says. "Let's have kids reflect. You can still have the routine and you can still have your workspace, but now it's for reading. I often say to parents, if we can put a man on the moon, we can put a man or woman on Mars and that person is now a second-grader. We don't know what skills that person will need. At the end of the day, we have to feel confident that we're giving them something they can use on Mars."

Read a January 2014 update.

Homework Policy Still Going Strong

Ed. Magazine

The magazine of the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Commencement Marshal Sarah Fiarman: The Principal of the Matter

Making Math “Almost Fun”

Alum develops curriculum to entice reluctant math learners

Reshaping Teacher Licensure: Lessons from the Pandemic

Olivia Chi, Ed.M.'17, Ph.D.'20, discusses the ongoing efforts to ensure the quality and stability of the teaching workforce

Status updates

The New York Times

Motherlode | the mechanics of homework, the mechanics of homework.

The homework wars among education wonks, teachers and parents don’t, as my friend and colleague Bruce Feiler writes in “The Homework Squabbles,” his This Life column for Sunday Styles, matter much on the scale at which most families are dealing with homework. To us, the question of how valuable homework is has to be set aside daily in the name of the backpacks, folders, binders and worksheets full of the stuff that our children actually bring home. And it’s worth noting that this idea of “too much homework” as a national problem is a myth . Instead, homework is something of an ironic twist in the American inequality story, with the more pressing problem being with the children who have too little rather than those who have too much.

But for the privileged families to whom homework unquestionably does not feel like a privilege (and mine is one of them), the mechanics of how to get the homework done loom large. Especially at this time of year, as parents and students are getting back into the groove of homework, questions of when and how and where can make us feel like we’re once again reinventing the homework wheel. That’s true at my house. In spite of a long-standing hands-off approach, and an attempt to set timers to focus my younger children on staying on task while limiting the time homework takes, homework is really wreaking havoc on our afternoons and evenings.

Bruce pulled together advice from experts and from parents whose experience makes them expert on everything from the when and where of homework to how involved a parent should be. How is the self-reliance we all hope our children will achieve best encouraged? What kind of help motivates, and what kind is too much? Is there any defense for the beloved teenage (and adult) habit of multitasking? Their answers are worth reading .

In spite of our timers (which we’re using more when necessary than as a habit, with two children relying more on them than others), and in spite of the fact that at the moment, homework is feeling like an instrument of torture designed to destroy my relationship with my two younger children, homework mechanics at our house haven’t changed much this year, and they won’t. It’s done in the kitchen unless you’d prefer to go elsewhere, or unless your method of objecting to the homework you’ve been given is detrimental to the ability of others to do theirs. Need help? I help sound out spelling on difficult words, but your teacher doesn’t want to know what I’ve learned through research about horse hooves. Frustrated with how much there is? I sing one song again and again in many keys: If you put the time into doing the homework that you’ve put into complaining about it, you’d be done by now. Just put one foot in front of the other, my friend.

Right now, two weeks in, it feels like I’ll be repeating myself all year. Like we’ll never pass another evening without a child strewn across the floor of the kitchen, screaming “but it’s too hard” or somehow managing to spend 90 minutes copying 20 spelling words 3 times each. Like every night, the homework, timers or no, will drag on past dinner, past soccer practice, toward bedtime and beyond.

But I’m relying on the curative powers of time and habit to work their magic. I know that what takes over an hour now will take far less time once my children stop spinning their pencils and get down to it. I know that once she knows it isn’t going to help, the child will get up off the floor and get it done. And I know that the homework habit, timers or no, takes time to develop.

We go through this every September. Some things change, some thing stay the same. The second grader who could gaze into space for hours at our house turned into the fifth grader who could buckle down, but couldn’t plan, who eventually turned into the eighth grader who knows that if it’s due next week, now’s the time to start, even if he doesn’t always pull it off. He still has plenty of room to improve, but he will. His siblings, I hope, will follow, but it doesn’t have to happen — it isn’t going to happen — today, or even this week.

What will happen is that the mechanics, like everything else, will evolve along with the children and the year. Some nights homework will progress in an orderly fashion in the kitchen; other nights someone will be stuck doing it in the lobby of a hockey rink. Some projects will happen in a timely way, others will be left until the last minute. Some homework will be a child’s best work. Some won’t be done at all.

When things go wrong‚ and they will, I’ll fall back on this: Learning to deal with your mistakes and roll with the things you can’t control is an important lesson. The one thing I know about homework at our house is that it’s pretty much guaranteed to offer my kids the opportunity to learn it.

Note: The original post stated that the author’s children were capable of spending 90 minutes copying 20 spelling words 30 times each. They have never been assigned so much; they are asked to copy the words 3 times each.

What's Next

IMAGES

COMMENTS

"Homework has perennially acted as a source of stress for students, so that piece of it is not new," Galloway says. "But especially in upper-middle-class communities, where the focus is on getting ahead, I think the pressure on students has been ratcheted up." Yet homework can be a problem at the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum as well.

A Stanford researcher found that students in high-achieving communities who spend too much time on homework experience more stress, physical health problems, a lack of balance and even alienation ...

The researchers also found that spending too much time on homework meant that students were not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills. Students were more ...

“In middle school and high school, homework is important because it helps build stamina and potential study habits for college or trade schools.” —Desiree T., elementary teacher “Homework is good practice for subjects like math. In other subjects, it is good for reviewing subject matter.” —Ohio 8th grade social studies teacher

Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth and a strong believer in eliminating all homework, writes that, "The fact that there isn't anything close to unanimity among experts belies the widespread assumption that homework helps." At best, he says, homework shows only an association, not a causal relationship, with academic achievement.

Im a sophomore and there is a plethora amount of homework its crazy especially from Ap World History in which im always getting projects and english sometimes i stay up late till 12 am and then continue my homework at school during breakfast sometimes students in grade levels below mine have to stay after school and during school for something ...

Student Opinion: Homework is torture Some believe homework should be optional because it causes stress and takes away from free time. Photo: Westend61/Getty Images

In spite of our timers (which we’re using more when necessary than as a habit, with two children relying more on them than others), and in spite of the fact that at the moment, homework is feeling like an instrument of torture designed to destroy my relationship with my two younger children, homework mechanics at our house haven’t changed ...

2022] TORTURE IN OUR SCHOOLS? 513 misguided legislative policy preferences, but a violation of their funda-mental legal rights. The most directly applicable treaty on ill-treatment (but not the only one) is the U.N. Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment5 (UNCAT or the Torture Convention).

Homework has been a deeply rooted feature of the primary and secondary education system for well over a century. And it’s an extremely divisive topic—homework seems to be considered either all good or all bad. There’s no in-between. Throughout the 20th century, the debate about homework seemed to be guided by cultural and political pressures.