What is a Directional Hypothesis? (Definition & Examples)

A statistical hypothesis is an assumption about a population parameter . For example, we may assume that the mean height of a male in the U.S. is 70 inches.

The assumption about the height is the statistical hypothesis and the true mean height of a male in the U.S. is the population parameter .

To test whether a statistical hypothesis about a population parameter is true, we obtain a random sample from the population and perform a hypothesis test on the sample data.

Whenever we perform a hypothesis test, we always write down a null and alternative hypothesis:

- Null Hypothesis (H 0 ): The sample data occurs purely from chance.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H A ): The sample data is influenced by some non-random cause.

A hypothesis test can either contain a directional hypothesis or a non-directional hypothesis:

- Directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the less than (“<“) or greater than (“>”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is a positive or negative effect.

- Non-directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the not equal (“≠”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is some effect, without specifying the direction of the effect.

Note that directional hypothesis tests are also called “one-tailed” tests and non-directional hypothesis tests are also called “two-tailed” tests.

Check out the following examples to gain a better understanding of directional vs. non-directional hypothesis tests.

Example 1: Baseball Programs

A baseball coach believes a certain 4-week program will increase the mean hitting percentage of his players, which is currently 0.285.

To test this, he measures the hitting percentage of each of his players before and after participating in the program.

He then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = .285 (the program will have no effect on the mean hitting percentage)

- H A : μ > .285 (the program will cause mean hitting percentage to increase)

This is an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the greater than “>” sign. The coach believes that the program will influence the mean hitting percentage of his players in a positive direction.

Example 2: Plant Growth

A biologist believes that a certain pesticide will cause plants to grow less during a one-month period than they normally do, which is currently 10 inches.

To test this, she applies the pesticide to each of the plants in her laboratory for one month.

She then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = 10 inches (the pesticide will have no effect on the mean plant growth)

- H A : μ < 10 inches (the pesticide will cause mean plant growth to decrease)

This is also an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the less than “<” sign. The biologist believes that the pesticide will influence the mean plant growth in a negative direction.

Example 3: Studying Technique

A professor believes that a certain studying technique will influence the mean score that her students receive on a certain exam, but she’s unsure if it will increase or decrease the mean score, which is currently 82.

To test this, she lets each student use the studying technique for one month leading up to the exam and then administers the same exam to each of the students.

- H 0 : μ = 82 (the studying technique will have no effect on the mean exam score)

- H A : μ ≠ 82 (the studying technique will cause the mean exam score to be different than 82)

This is an example of a non-directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the not equal “≠” sign. The professor believes that the studying technique will influence the mean exam score, but doesn’t specify whether it will cause the mean score to increase or decrease.

Additional Resources

Introduction to Hypothesis Testing Introduction to the One Sample t-test Introduction to the Two Sample t-test Introduction to the Paired Samples t-test

Featured Posts

Hey there. My name is Zach Bobbitt. I have a Masters of Science degree in Applied Statistics and I’ve worked on machine learning algorithms for professional businesses in both healthcare and retail. I’m passionate about statistics, machine learning, and data visualization and I created Statology to be a resource for both students and teachers alike. My goal with this site is to help you learn statistics through using simple terms, plenty of real-world examples, and helpful illustrations.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Join the Statology Community

Sign up to receive Statology's exclusive study resource: 100 practice problems with step-by-step solutions. Plus, get our latest insights, tutorials, and data analysis tips straight to your inbox!

By subscribing you accept Statology's Privacy Policy.

psychologyrocks

Hypotheses; directional and non-directional, what is the difference between an experimental and an alternative hypothesis.

Nothing much! If the study is a true experiment then we can call the hypothesis “an experimental hypothesis”, a prediction is made about how the IV causes an effect on the DV. In a study which does not involve the direct manipulation of an IV, i.e. a natural or quasi-experiment or any other quantitative research method (e.g. survey) has been used, then we call it an “alternative hypothesis”, it is the alternative to the null.

Directional hypothesis: A directional (or one-tailed hypothesis) states which way you think the results are going to go, for example in an experimental study we might say…”Participants who have been deprived of sleep for 24 hours will have more cold symptoms the week after exposure to a virus than participants who have not been sleep deprived”; the hypothesis compares the two groups/conditions and states which one will ….have more/less, be quicker/slower, etc.

If we had a correlational study, the directional hypothesis would state whether we expect a positive or a negative correlation, we are stating how the two variables will be related to each other, e.g. there will be a positive correlation between the number of stressful life events experienced in the last year and the number of coughs and colds suffered, whereby the more life events you have suffered the more coughs and cold you will have had”. The directional hypothesis can also state a negative correlation, e.g. the higher the number of face-book friends, the lower the life satisfaction score “

Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional (or two tailed hypothesis) simply states that there will be a difference between the two groups/conditions but does not say which will be greater/smaller, quicker/slower etc. Using our example above we would say “There will be a difference between the number of cold symptoms experienced in the following week after exposure to a virus for those participants who have been sleep deprived for 24 hours compared with those who have not been sleep deprived for 24 hours.”

When the study is correlational, we simply state that variables will be correlated but do not state whether the relationship will be positive or negative, e.g. there will be a significant correlation between variable A and variable B.

Null hypothesis The null hypothesis states that the alternative or experimental hypothesis is NOT the case, if your experimental hypothesis was directional you would say…

Participants who have been deprived of sleep for 24 hours will NOT have more cold symptoms in the following week after exposure to a virus than participants who have not been sleep deprived and any difference that does arise will be due to chance alone.

or with a directional correlational hypothesis….

There will NOT be a positive correlation between the number of stress life events experienced in the last year and the number of coughs and colds suffered, whereby the more life events you have suffered the more coughs and cold you will have had”

With a non-directional or two tailed hypothesis…

There will be NO difference between the number of cold symptoms experienced in the following week after exposure to a virus for those participants who have been sleep deprived for 24 hours compared with those who have not been sleep deprived for 24 hours.

or for a correlational …

there will be NO correlation between variable A and variable B.

When it comes to conducting an inferential stats test, if you have a directional hypothesis , you must do a one tailed test to find out whether your observed value is significant. If you have a non-directional hypothesis , you must do a two tailed test .

Exam Techniques/Advice

- Remember, a decent hypothesis will contain two variables, in the case of an experimental hypothesis there will be an IV and a DV; in a correlational hypothesis there will be two co-variables

- both variables need to be fully operationalised to score the marks, that is you need to be very clear and specific about what you mean by your IV and your DV; if someone wanted to repeat your study, they should be able to look at your hypothesis and know exactly what to change between the two groups/conditions and exactly what to measure (including any units/explanation of rating scales etc, e.g. “where 1 is low and 7 is high”)

- double check the question, did it ask for a directional or non-directional hypothesis?

- if you were asked for a null hypothesis, make sure you always include the phrase “and any difference/correlation (is your study experimental or correlational?) that does arise will be due to chance alone”

Practice Questions:

- Mr Faraz wants to compare the levels of attendance between his psychology group and those of Mr Simon, who teaches a different psychology group. Which of the following is a suitable directional (one tailed) hypothesis for Mr Faraz’s investigation?

A There will be a difference in the levels of attendance between the two psychology groups.

B Students’ level of attendance will be higher in Mr Faraz’s group than Mr Simon’s group.

C Any difference in the levels of attendance between the two psychology groups is due to chance.

D The level of attendance of the students will depend upon who is teaching the groups.

2. Tracy works for the local council. The council is thinking about reducing the number of people it employs to pick up litter from the street. Tracy has been asked to carry out a study to see if having the streets cleaned at less regular intervals will affect the amount of litter the public will drop. She studies a street to compare how much litter is dropped at two different times, once when it has just been cleaned and once after it has not been cleaned for a month.

Write a fully operationalised non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis for Tracy’s study. (2)

3. Jamila is conducting a practical investigation to look at gender differences in carrying out visuo-spatial tasks. She decides to give males and females a jigsaw puzzle and will time them to see who completes it the fastest. She uses a random sample of pupils from a local school to get her participants.

(a) Write a fully operationalised directional (one tailed) hypothesis for Jamila’s study. (2) (b) Outline one strength and one weakness of the random sampling method. You may refer to Jamila’s use of this type of sampling in your answer. (4)

4. Which of the following is a non-directional (two tailed) hypothesis?

A There is a difference in driving ability with men being better drivers than women

B Women are better at concentrating on more than one thing at a time than men

C Women spend more time doing the cooking and cleaning than men

D There is a difference in the number of men and women who participate in sports

Revision Activities

writing-hypotheses-revision-sheet

Quizizz link for teachers: https://quizizz.com/admin/quiz/5bf03f51add785001bc5a09e

By Psychstix by Mandy wood

Share this:

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

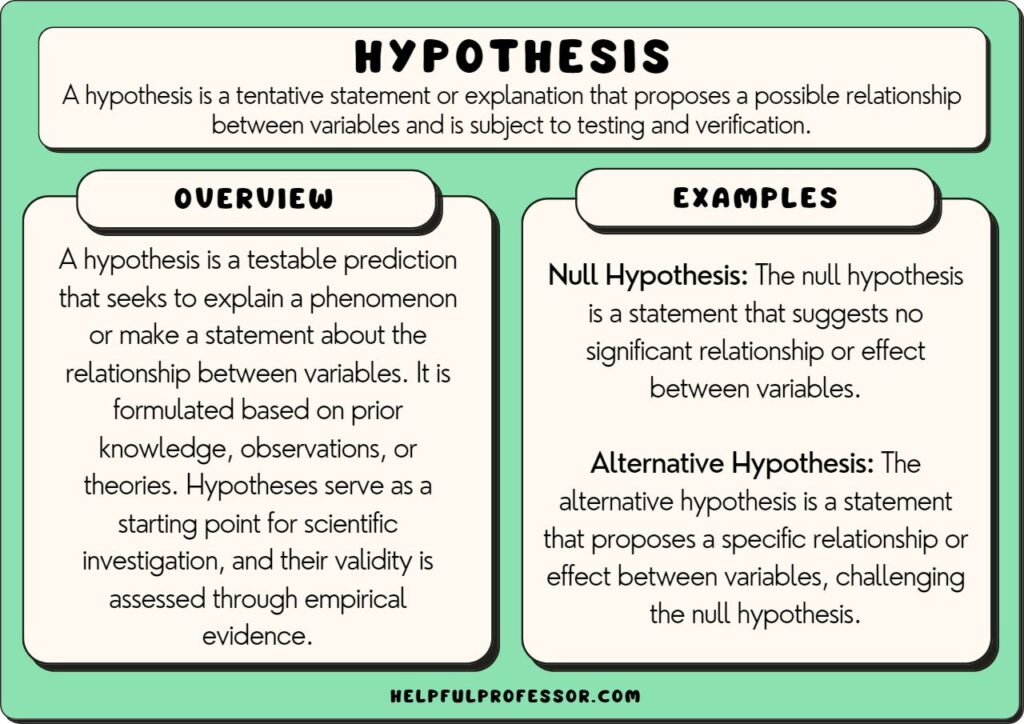

13 Different Types of Hypothesis

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

There are 13 different types of hypothesis. These include simple, complex, null, alternative, composite, directional, non-directional, logical, empirical, statistical, associative, exact, and inexact.

A hypothesis can be categorized into one or more of these types. However, some are mutually exclusive and opposites. Simple and complex hypotheses are mutually exclusive, as are direction and non-direction, and null and alternative hypotheses.

Below I explain each hypothesis in simple terms for absolute beginners. These definitions may be too simple for some, but they’re designed to be clear introductions to the terms to help people wrap their heads around the concepts early on in their education about research methods .

Types of Hypothesis

Before you Proceed: Dependent vs Independent Variables

A research study and its hypotheses generally examine the relationships between independent and dependent variables – so you need to know these two concepts:

- The independent variable is the variable that is causing a change.

- The dependent variable is the variable the is affected by the change. This is the variable being tested.

Read my full article on dependent vs independent variables for more examples.

Example: Eating carrots (independent variable) improves eyesight (dependent variable).

1. Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a hypothesis that predicts a correlation between two test variables: an independent and a dependent variable.

This is the easiest and most straightforward type of hypothesis. You simply need to state an expected correlation between the dependant variable and the independent variable.

You do not need to predict causation (see: directional hypothesis). All you would need to do is prove that the two variables are linked.

Simple Hypothesis Examples

2. complex hypothesis.

A complex hypothesis is a hypothesis that contains multiple variables, making the hypothesis more specific but also harder to prove.

You can have multiple independent and dependant variables in this hypothesis.

Complex Hypothesis Example

In the above example, we have multiple independent and dependent variables:

- Independent variables: Age and weight.

- Dependent variables: diabetes and heart disease.

Because there are multiple variables, this study is a lot more complex than a simple hypothesis. It quickly gets much more difficult to prove these hypotheses. This is why undergraduate and first-time researchers are usually encouraged to use simple hypotheses.

3. Null Hypothesis

A null hypothesis will predict that there will be no significant relationship between the two test variables.

For example, you can say that “The study will show that there is no correlation between marriage and happiness.”

A good way to think about a null hypothesis is to think of it in the same way as “innocent until proven guilty”[1]. Unless you can come up with evidence otherwise, your null hypothesis will stand.

A null hypothesis may also highlight that a correlation will be inconclusive . This means that you can predict that the study will not be able to confirm your results one way or the other. For example, you can say “It is predicted that the study will be unable to confirm a correlation between the two variables due to foreseeable interference by a third variable .”

Beware that an inconclusive null hypothesis may be questioned by your teacher. Why would you conduct a test that you predict will not provide a clear result? Perhaps you should take a closer look at your methodology and re-examine it. Nevertheless, inconclusive null hypotheses can sometimes have merit.

Null Hypothesis Examples

4. alternative hypothesis.

An alternative hypothesis is a hypothesis that is anything other than the null hypothesis. It will disprove the null hypothesis.

We use the symbol H A or H 1 to denote an alternative hypothesis.

The null and alternative hypotheses are usually used together. We will say the null hypothesis is the case where a relationship between two variables is non-existent. The alternative hypothesis is the case where there is a relationship between those two variables.

The following statement is always true: H 0 ≠ H A .

Let’s take the example of the hypothesis: “Does eating oatmeal before an exam impact test scores?”

We can have two hypotheses here:

- Null hypothesis (H 0 ): “Eating oatmeal before an exam does not impact test scores.”

- Alternative hypothesis (H A ): “Eating oatmeal before an exam does impact test scores.”

For the alternative hypothesis to be true, all we have to do is disprove the null hypothesis for the alternative hypothesis to be true. We do not need an exact prediction of how much oatmeal will impact the test scores or even if the impact is positive or negative. So long as the null hypothesis is proven to be false, then the alternative hypothesis is proven to be true.

5. Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a hypothesis that does not predict the exact parameters, distribution, or range of the dependent variable.

Often, we would predict an exact outcome. For example: “23 year old men are on average 189cm tall.” Here, we are giving an exact parameter. So, the hypothesis is not composite.

But, often, we cannot exactly hypothesize something. We assume that something will happen, but we’re not exactly sure what. In these cases, we might say: “23 year old men are not on average 189cm tall.”

We haven’t set a distribution range or exact parameters of the average height of 23 year old men. So, we’ve introduced a composite hypothesis as opposed to an exact hypothesis.

Generally, an alternative hypothesis (discussed above) is composite because it is defined as anything except the null hypothesis. This ‘anything except’ does not define parameters or distribution, and therefore it’s an example of a composite hypothesis.

6. Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis makes a prediction about the positivity or negativity of the effect of an intervention prior to the test being conducted.

Instead of being agnostic about whether the effect will be positive or negative, it nominates the effect’s directionality.

We often call this a one-tailed hypothesis (in contrast to a two-tailed or non-directional hypothesis) because, looking at a distribution graph, we’re hypothesizing that the results will lean toward one particular tail on the graph – either the positive or negative.

Directional Hypothesis Examples

7. non-directional hypothesis.

A non-directional hypothesis does not specify the predicted direction (e.g. positivity or negativity) of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable.

These hypotheses predict an effect, but stop short of saying what that effect will be.

A non-directional hypothesis is similar to composite and alternative hypotheses. All three types of hypothesis tend to make predictions without defining a direction. In a composite hypothesis, a specific prediction is not made (although a general direction may be indicated, so the overlap is not complete). For an alternative hypothesis, you often predict that the even will be anything but the null hypothesis, which means it could be more or less than H 0 (or in other words, non-directional).

Let’s turn the above directional hypotheses into non-directional hypotheses.

Non-Directional Hypothesis Examples

8. logical hypothesis.

A logical hypothesis is a hypothesis that cannot be tested, but has some logical basis underpinning our assumptions.

These are most commonly used in philosophy because philosophical questions are often untestable and therefore we must rely on our logic to formulate logical theories.

Usually, we would want to turn a logical hypothesis into an empirical one through testing if we got the chance. Unfortunately, we don’t always have this opportunity because the test is too complex, expensive, or simply unrealistic.

Here are some examples:

- Before the 1980s, it was hypothesized that the Titanic came to its resting place at 41° N and 49° W, based on the time the ship sank and the ship’s presumed path across the Atlantic Ocean. However, due to the depth of the ocean, it was impossible to test. Thus, the hypothesis was simply a logical hypothesis.

- Dinosaurs closely related to Aligators probably had green scales because Aligators have green scales. However, as they are all extinct, we can only rely on logic and not empirical data.

9. Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is the opposite of a logical hypothesis. It is a hypothesis that is currently being tested using scientific analysis. We can also call this a ‘working hypothesis’.

We can to separate research into two types: theoretical and empirical. Theoretical research relies on logic and thought experiments. Empirical research relies on tests that can be verified by observation and measurement.

So, an empirical hypothesis is a hypothesis that can and will be tested.

- Raising the wage of restaurant servers increases staff retention.

- Adding 1 lb of corn per day to cows’ diets decreases their lifespan.

- Mushrooms grow faster at 22 degrees Celsius than 27 degrees Celsius.

Each of the above hypotheses can be tested, making them empirical rather than just logical (aka theoretical).

10. Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis utilizes representative statistical models to draw conclusions about broader populations.

It requires the use of datasets or carefully selected representative samples so that statistical inference can be drawn across a larger dataset.

This type of research is necessary when it is impossible to assess every single possible case. Imagine, for example, if you wanted to determine if men are taller than women. You would be unable to measure the height of every man and woman on the planet. But, by conducting sufficient random samples, you would be able to predict with high probability that the results of your study would remain stable across the whole population.

You would be right in guessing that almost all quantitative research studies conducted in academic settings today involve statistical hypotheses.

Statistical Hypothesis Examples

- Human Sex Ratio. The most famous statistical hypothesis example is that of John Arbuthnot’s sex at birth case study in 1710. Arbuthnot used birth data to determine with high statistical probability that there are more male births than female births. He called this divine providence, and to this day, his findings remain true: more men are born than women.

- Lady Testing Tea. A 1935 study by Ronald Fisher involved testing a woman who believed she could tell whether milk was added before or after water to a cup of tea. Fisher gave her 4 cups in which one randomly had milk placed before the tea. He repeated the test 8 times. The lady was correct each time. Fisher found that she had a 1 in 70 chance of getting all 8 test correct, which is a statistically significant result.

11. Associative Hypothesis

An associative hypothesis predicts that two variables are linked but does not explore whether one variable directly impacts upon the other variable.

We commonly refer to this as “ correlation does not mean causation ”. Just because there are a lot of sick people in a hospital, it doesn’t mean that the hospital made the people sick. There is something going on there that’s causing the issue (sick people are flocking to the hospital).

So, in an associative hypothesis, you note correlation between an independent and dependent variable but do not make a prediction about how the two interact. You stop short of saying one thing causes another thing.

Associative Hypothesis Examples

- Sick people in hospital. You could conduct a study hypothesizing that hospitals have more sick people in them than other institutions in society. However, you don’t hypothesize that the hospitals caused the sickness.

- Lice make you healthy. In the Middle Ages, it was observed that sick people didn’t tend to have lice in their hair. The inaccurate conclusion was that lice was not only a sign of health, but that they made people healthy. In reality, there was an association here, but not causation. The fact was that lice were sensitive to body temperature and fled bodies that had fevers.

12. Causal Hypothesis

A causal hypothesis predicts that two variables are not only associated, but that changes in one variable will cause changes in another.

A causal hypothesis is harder to prove than an associative hypothesis because the cause needs to be definitively proven. This will often require repeating tests in controlled environments with the researchers making manipulations to the independent variable, or the use of control groups and placebo effects .

If we were to take the above example of lice in the hair of sick people, researchers would have to put lice in sick people’s hair and see if it made those people healthier. Researchers would likely observe that the lice would flee the hair, but the sickness would remain, leading to a finding of association but not causation.

Causal Hypothesis Examples

13. exact vs. inexact hypothesis.

For brevity’s sake, I have paired these two hypotheses into the one point. The reality is that we’ve already seen both of these types of hypotheses at play already.

An exact hypothesis (also known as a point hypothesis) specifies a specific prediction whereas an inexact hypothesis assumes a range of possible values without giving an exact outcome. As Helwig [2] argues:

“An “exact” hypothesis specifies the exact value(s) of the parameter(s) of interest, whereas an “inexact” hypothesis specifies a range of possible values for the parameter(s) of interest.”

Generally, a null hypothesis is an exact hypothesis whereas alternative, composite, directional, and non-directional hypotheses are all inexact.

See Next: 15 Hypothesis Examples

This is introductory information that is basic and indeed quite simplified for absolute beginners. It’s worth doing further independent research to get deeper knowledge of research methods and how to conduct an effective research study. And if you’re in education studies, don’t miss out on my list of the best education studies dissertation ideas .

[1] https://jnnp.bmj.com/content/91/6/571.abstract

[2] http://users.stat.umn.edu/~helwig/notes/SignificanceTesting.pdf

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Free Social Skills Worksheets

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

2 thoughts on “13 Different Types of Hypothesis”

Wow! This introductionary materials are very helpful. I teach the begginers in research for the first time in my career. The given tips and materials are very helpful. Chris, thank you so much! Excellent materials!

You’re more than welcome! If you want a pdf version of this article to provide for your students to use as a weekly reading on in-class discussion prompt for seminars, just drop me an email in the Contact form and I’ll get one sent out to you.

When I’ve taught this seminar, I’ve put my students into groups, cut these definitions into strips, and handed them out to the groups. Then I get them to try to come up with hypotheses that fit into each ‘type’. You can either just rotate hypothesis types so they get a chance at creating a hypothesis of each type, or get them to “teach” their hypothesis type and examples to the class at the end of the seminar.

Cheers, Chris

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The What, Why and How of Directional Hypotheses

In the world of research and science, hypotheses serve as the starting blocks, setting the pace for the entire study. One such hypothesis type is the directional hypothesis. Here, we delve into what exactly a directional hypothesis is, its significance, and the nitty-gritty of formulating one, followed by pitfalls to avoid and how to apply it in practical situations.

The What: Understanding the Concept of a Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis, often referred to as a one-tailed hypothesis, is an essential part of research that predicts the expected outcomes and their directions. The intriguing aspect here is that it goes beyond merely predicting a difference or connection, it actually suggests the direction that this difference or connection will take.

Let's break it down a bit. If the directional hypothesis is positive, this suggests that the variables being studied are expected to either increase or decrease in unison. On the other hand, if the hypothesis is negative, it implies that the variables will move in opposite directions - as one variable ascends, the other will descend, and vice versa.

This intricacy gives the directional hypothesis its unique value in research and offers a fascinating aspect of study predictions. With a clearer understanding of what a directional hypothesis is, we can now delve into why it holds such significance in research and how to construct one effectively.

The Why: The Significance of a Directional Hypothesis in Research

Ever wondered why the directional hypothesis is held in such high regard? The secret lies in its unique blend of precision and specificity. It provides an edge by paving the way for a more concentrated and focused investigation. Essentially, it helps scientists to have an informed prediction of the correlation between variables, underpinned by prior research, theoretical assumptions, or logical reasoning. This isn't just a game of guesswork but a highly credible route to more definitive and dependable results. As they say, the devil is in the detail. By using a directional hypothesis, we are able to dive into the intricate and exciting world of research, adding a robust foundation to our endeavours, ultimately boosting the credibility and reliability of our findings. By standing firmly on the shoulders of the directional hypothesis, we allow our research to gaze further and see clearer.

The How: Constructing a Strong Directional Hypothesis

Crafting a robust directional hypothesis is indeed a craft that requires a blend of art and science. This process starts with a comprehensive exploration of related literature, immersing oneself in the reservoir of knowledge that already exists around your subject of interest. This immersion enables you to soak up invaluable insights, creating a well-informed base from which to make educated predictions about the directionality between your variables of interest.

The process doesn't stop at a literature review. It's also imperative to fully comprehend your subject. Dive deeper into the layers of your topic, unpick the threads, and question the status quo. Understand what drives your variables, how they may interact, and why you anticipate they'll behave in a certain way.

Then, it's time to define your variables clearly and precisely. This might sound simple, but it's crucial to be as accurate as possible. By doing so, you not only ensure a clear understanding of what you are measuring, but you also set clear parameters for your research.

Following that, comes the exciting part - predicting the direction of the relationship between your variables. This prediction should not be a wild guess, but an informed forecast grounded in your literature review, understanding of the subject, and clear definition of variables.

Finally, remember that a directional hypothesis is not set in stone. It is, by definition, a hypothesis - a proposed explanation or prediction that is subject to testing and verification. So, don’t be disheartened if your directional hypothesis doesn’t pan out as expected. Instead, see it as an opportunity to delve further, learn more and further the boundaries of knowledge in your field. After all, research is not just about confirming hypotheses, but also about the thrill of exploration, discovery, and ultimately, growth.

Pitfalls to Avoid When Formulating a Directional Hypothesis

Crafting a directional hypothesis isn't a walk in the park. A few common missteps can muddy the waters and limit the effectiveness of your hypothesis. The first stumbling block that researchers should watch out for is making baseless presumptions. Although predicting the course of the relationship between variables is integral to a directional hypothesis, this prediction should be firmly rooted in evidence, not just whims or gut feelings.

Secondly, steer clear of being excessively rigid with your hypothesis. Remember, it's a guide, not gospel truth. Science is about exploration, about finding out, about being open to unexpected outcomes. If your hypothesis does not match the results, that's not failure; it's a chance to learn and expand your understanding.

Avoid creating an overly complex hypothesis. Simplicity is the name of the game. You want your hypothesis to be clear, concise, and comprehensible, not wrapped in jargon and unnecessary complexities.

Lastly, ensure that your directional hypothesis is testable. It's not enough to merely state a prediction; it needs to be something you can verify empirically. If it can't be tested, it's not a viable hypothesis. So, when creating your directional hypothesis, be mindful to keep it within the realm of testable claims.

Remember, falling into these traps can derail your research and limit the value of your findings. By keeping these pitfalls at bay, you are better equipped to navigate the fascinating labyrinth of research, while contributing to a deeper understanding of your field. Happy hypothesising!

Putting it All Together: Applying a Directional Hypothesis in Practice

When it comes to applying a directional hypothesis, the real fun begins as you put your prediction to the test using appropriate research methodologies and statistical techniques. Let's put this into perspective using an example. Suppose you're exploring the effect of physical activity on people's mood. Your directional hypothesis might suggest that engaging in exercise would result in an improvement in mood ratings.

To test this hypothesis, you could employ a repeated-measures design. Here, you measure the moods of your participants before they start the exercise routine and then again after they've completed it. If the data reveals an uplift in positive mood ratings post-exercise, you would have empirical evidence to support your directional hypothesis.

However, bear in mind that your findings might not always corroborate your prediction. And that's the beauty of research! Contradictory findings don't necessarily signify failure. Instead, they open up new avenues of inquiry, challenging us to refine our understanding and fuel our intellectual curiosity. Therefore, whether your directional hypothesis is proven correct or not, it still serves a valuable purpose by guiding your exploration and contributing to the ever-evolving body of knowledge in your field. So, go ahead and plunge into the exciting world of research with your well-crafted directional hypothesis, ready to embrace whatever comes your way with open arms. Happy researching!

Directional Hypothesis

Definition:

A directional hypothesis is a specific type of hypothesis statement in which the researcher predicts the direction or effect of the relationship between two variables.

Key Features

1. Predicts direction:

Unlike a non-directional hypothesis, which simply states that there is a relationship between two variables, a directional hypothesis specifies the expected direction of the relationship.

2. Involves one-tailed test:

Directional hypotheses typically require a one-tailed statistical test, as they are concerned with whether the relationship is positive or negative, rather than simply whether a relationship exists.

3. Example:

An example of a directional hypothesis would be: “Increasing levels of exercise will result in greater weight loss.”

4. Researcher’s prior belief:

A directional hypothesis is often formed based on the researcher’s prior knowledge, theoretical understanding, or previous empirical evidence relating to the variables under investigation.

5. Confirmatory nature:

Directional hypotheses are considered confirmatory, as they provide a specific prediction that can be tested statistically, allowing researchers to either support or reject the hypothesis.

6. Advantages and disadvantages:

Directional hypotheses help focus the research by explicitly stating the expected relationship, but they can also limit exploration of alternative explanations or unexpected findings.

What is a directional hypothesis?

Table of Contents

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction (positive or negative) of a relationship between two variables. It is used to determine the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable. It is often tested using statistical methods such as correlation or regression. Directional hypotheses are often used in research studies to determine cause-and-effect relationships.

A statistical hypothesis is an assumption about a . For example, we may assume that the mean height of a male in the U.S. is 70 inches.

The assumption about the height is the statistical hypothesis and the true mean height of a male in the U.S. is the population parameter .

To test whether a statistical hypothesis about a population parameter is true, we obtain a random sample from the population and perform a hypothesis test on the sample data.

Whenever we perform a hypothesis test, we always write down a null and alternative hypothesis:

- Null Hypothesis (H 0 ): The sample data occurs purely from chance.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H A ): The sample data is influenced by some non-random cause.

A hypothesis test can either contain a directional hypothesis or a non-directional hypothesis:

- Directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the less than (“<“) or greater than (“>”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is a positive or negative effect.

- Non-directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the not equal (“≠”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is some effect, without specifying the direction of the effect.

Note that directional hypothesis tests are also called “one-tailed” tests and non-directional hypothesis tests are also called “two-tailed” tests.

Check out the following examples to gain a better understanding of directional vs. non-directional hypothesis tests.

Example 1: Baseball Programs

A baseball coach believes a certain 4-week program will increase the mean hitting percentage of his players, which is currently 0.285.

To test this, he measures the hitting percentage of each of his players before and after participating in the program.

He then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = .285 (the program will have no effect on the mean hitting percentage)

- H A : μ > .285 (the program will cause mean hitting percentage to increase)

This is an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the greater than “>” sign. The coach believes that the program will influence the mean hitting percentage of his players in a positive direction.

Example 2: Plant Growth

A biologist believes that a certain pesticide will cause plants to grow less during a one-month period than they normally do, which is currently 10 inches.

She then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = 10 inches (the pesticide will have no effect on the mean plant growth)

- H A : μ < 10 inches (the pesticide will cause mean plant growth to decrease)

This is also an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the less than “<” sign. The biologist believes that the pesticide will influence the mean plant growth in a negative direction.

Example 3: Studying Technique

A professor believes that a certain studying technique will influence the mean score that her students receive on a certain exam, but she’s unsure if it will increase or decrease the mean score, which is currently 82.

To test this, she lets each student use the studying technique for one month leading up to the exam and then administers the same exam to each of the students.

- H 0 : μ = 82 (the studying technique will have no effect on the mean exam score)

- H A : μ ≠ 82 (the studying technique will cause the mean exam score to be different than 82)

This is an example of a non-directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the not equal “≠” sign. The professor believes that the studying technique will influence the mean exam score, but doesn’t specify whether it will cause the mean score to increase or decrease.

Related terms:

- Directional Hypothesis

- Somatic Markers Hypothesis (Antonio Damasio)

- Critical Period Hypothesis

- Biophilia Hypothesis

- What’s the difference between a hypothesis test and confidence interval?

- How do you do Hypothesis Testing in Excel?

- What is the Null Hypothesis for Logistic Regression?

- How to run a hypothesis testing in R?

- What is the Null Hypothesis for Linear Regression?

- 4 Examples of Hypothesis Testing in Real Life?

The Leading Source of Insights On Business Model Strategy & Tech Business Models

Directional Hypothesis

Directional hypotheses play a pivotal role in scientific research by guiding investigators in making specific predictions about the outcomes of their studies. These hypotheses provide a clear and testable statement about the expected direction of the relationship between variables. Whether in psychology, biology, economics, or any other scientific field, directional hypotheses enable researchers to formulate focused research questions, design experiments, and analyze data effectively.

Table of Contents

Understanding Directional Hypotheses

A hypothesis is a tentative statement or educated guess that predicts the relationship between variables in a research study. Hypotheses are essential components of the scientific method, serving as the foundation upon which research is built. While hypotheses can take various forms, including non-directional (or null) hypotheses, directional hypotheses offer a more specific and targeted approach to hypothesis testing.

Directional hypotheses , also known as one-tailed hypotheses, make explicit predictions about the direction of the relationship between variables. They state that a change in one variable will lead to a specific change in another variable, and they specify whether the change will be positive or negative. Directional hypotheses are commonly used when researchers have a clear theoretical basis or previous evidence to support their predictions.

In summary, directional hypotheses:

- Predict the direction of the expected relationship between variables.

- Specify whether the relationship will be positive or negative.

- Are based on theory or prior research.

The Structure of Directional Hypotheses

Directional hypotheses typically consist of two main components: the independent variable (IV) and the dependent variable (DV). The IV is the variable that researchers manipulate or examine for its effect on the DV, which is the variable that researchers measure or observe. Here is the general structure of a directional hypothesis:

“If [change in IV], then [specific change in DV].”

- “If” introduces the independent variable or the condition that is being manipulated.

- “[Change in IV]” specifies the nature of the change in the independent variable.

- “Then” signals the expected outcome or change in the dependent variable.

- “[Specific change in DV]” describes the direction (positive or negative) of the expected relationship between the variables.

Let’s break down the structure with a few examples:

- “If the amount of sunlight increases, then the plant growth will also increase.” (Positive relationship )

- “If the dosage of a drug decreases, then the pain experienced by patients will decrease.” (Negative relationship )

- “If the time spent studying for an exam increases, then the exam scores will improve.” (Positive relationship )

Significance and Advantages of Directional Hypotheses

Directional hypotheses offer several advantages in scientific research:

1. Precision:

- Directional hypotheses provide clear and specific predictions about the expected relationship between variables. This precision helps researchers design experiments and collect data with a well-defined focus.

2. Theory-Based Predictions:

- Researchers often formulate directional hypotheses based on existing theory or prior research. This theoretical foundation enhances the scientific validity of the study and contributes to the cumulative knowledge in the field.

3. Hypothesis Testing:

- Directional hypotheses facilitate hypothesis testing by allowing researchers to determine whether the observed results align with their specific predictions. This helps in drawing meaningful conclusions about the research question.

4. Efficient Data Analysis:

- When researchers use directional hypotheses, they can perform one-tailed statistical tests during data analysis . This approach increases the statistical power of the study, making it more likely to detect significant effects.

5. Practical Applications:

- Directional hypotheses are commonly used in applied research, where researchers seek to make practical predictions and recommendations. For example, in medicine or psychology, researchers may want to predict the effectiveness of a treatment or intervention.

Formulating Directional Hypotheses

Creating effective directional hypotheses requires a systematic approach. Here are the steps to formulate a directional hypothesis:

1. Identify the Variables:

- Start by identifying the independent and dependent variables in your study. These variables should be clearly defined and measurable.

2. Review Existing Literature:

- Conduct a thorough literature review to understand the existing knowledge and research related to your topic. This step helps you identify any theoretical or empirical evidence that can inform your hypothesis.

3. Formulate a Research Question:

- Based on your literature review and research goals, formulate a research question that addresses the relationship between the variables. This question serves as the foundation for your hypothesis.

4. Choose the Direction:

- Determine the expected direction of the relationship between the variables. Will it be a positive relationship (increases in one variable lead to increases in the other) or a negative relationship (increases in one variable lead to decreases in the other)?

5. Craft the Hypothesis:

- Use the structure mentioned earlier to craft your directional hypothesis. Be clear and specific about the changes in the independent and dependent variables and the expected direction of the relationship .

6. Ensure Testability:

- Ensure that your directional hypothesis is testable. This means that you should be able to collect data and analyze it to determine whether the observed results support or contradict your hypothesis.

7. Revise and Refine:

- Review your directional hypothesis and refine it as needed. Seek feedback from colleagues or mentors to improve the clarity and specificity of your hypothesis.

Examples of Directional Hypotheses

Directional hypotheses are used in various fields of research to make specific predictions. Here are some examples from different disciplines:

1. Psychology:

- Research Question: Does exposure to violent video games increase aggressive behavior in children?

- Directional Hypothesis: “If children are exposed to violent video games, then their aggressive behavior will increase.”

2. Biology:

- Research Question: How does temperature affect the rate of enzyme activity?

- Directional Hypothesis: “If the temperature increases, then the rate of enzyme activity will also increase.”

3. Economics:

- Research Question: Does an increase in the minimum wage lead to a decrease in unemployment rates?

- Directional Hypothesis: “If the minimum wage increases, then the unemployment rate will decrease.”

4. Education:

- Research Question: Does the use of interactive learning software improve students’ math skills?

- Directional Hypothesis: “If students use interactive learning software, then their math skills will improve.”

5. Sociology:

- Research Question: Does income inequality lead to higher crime rates in urban areas?

- Directional Hypothesis: “If income inequality increases in urban areas, then crime rates will also increase.”

Directional Hypotheses vs. Non-Directional (Null) Hypotheses

Directional hypotheses differ from non-directional (null) hypotheses in their focus and predictions:

- Directional Hypotheses make specific predictions about the direction of the relationship between variables. They state whether the relationship will be positive or negative.

- Non-Directional (Null) Hypotheses do not make specific predictions about the direction of the relationship . They typically state that there will be no significant relationship or difference between variables.

For example, in a study examining the effect of a new drug on blood pressure:

- Directional Hypothesis: “If participants take the new drug, then their blood pressure will decrease

- Non-Directional (Null) Hypothesis: “There will be no significant difference in blood pressure between participants who take the new drug and those who do not.”

Directional hypotheses are used when researchers have a clear expectation of the direction of the relationship based on theory or prior research. Non-directional hypotheses are used when researchers do not have a specific expectation and want to test for any possible relationship or difference.

Testing Directional Hypotheses

Once a directional hypothesis is formulated, researchers proceed with data collection and statistical analysis to test their predictions. The choice of statistical test depends on the nature of the variables and the research design . Common statistical tests for directional hypotheses include t-tests, chi-squared tests, and correlation analyses.

During the analysis , researchers compare the observed results to the predictions stated in the directional hypothesis. If the observed results align with the predicted direction of the relationship , the hypothesis is considered supported. If the observed results contradict the prediction, the hypothesis is not supported.

It’s important to note that not all directional hypotheses are supported by empirical data. In scientific research, both supported and unsupported hypotheses contribute to the advancement of knowledge. Unsupported hypotheses may lead to new questions, refinements in theory, or adjustments in research methods.

Directional hypotheses are powerful tools in scientific research, enabling researchers to make specific predictions about the relationship between variables. These hypotheses provide clarity, focus, and testability to research questions, contributing to the systematic advancement of knowledge across various disciplines.

By formulating and testing directional hypotheses, researchers can gain valuable insights, confirm or challenge existing theories, and ultimately expand our understanding of the complex phenomena that shape our world. Whether in the natural sciences, social sciences, or humanities, directional hypotheses continue to play a central role in the quest for scientific discovery and innovation .

Connected Thinking Frameworks

Convergent vs. Divergent Thinking

Critical Thinking

Second-Order Thinking

Lateral Thinking

Bounded Rationality

Dunning-Kruger Effect

Occam’s Razor

Lindy Effect

Antifragility

Systems Thinking

Vertical Thinking

Maslow’s Hammer

Peter Principle

Straw Man Fallacy

Streisand Effect

Recognition Heuristic

Representativeness Heuristic

Take-The-Best Heuristic

Bundling Bias

Barnum Effect

First-Principles Thinking

Ladder Of Inference

Goodhart’s Law

Six Thinking Hats Model

Mandela Effect

Crowding-Out Effect

Bandwagon Effect

Moore’s Law

Disruptive Innovation

Value Migration

Bye-Now Effect

Stereotyping

Murphy’s Law

Law of Unintended Consequences

Fundamental Attribution Error

Outcome Bias

Hindsight Bias

Read Next: Biases , Bounded Rationality , Mandela Effect , Dunning-Kruger Effect , Lindy Effect , Crowding Out Effect , Bandwagon Effect .

Main Guides:

- Business Models

- Business Strategy

- Marketing Strategy

- Business Model Innovation

- Platform Business Models

- Network Effects In A Nutshell

- Digital Business Models

More Resources

About The Author

Gennaro Cuofano

Discover more from fourweekmba.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

an Excelsior University site

Types of Research Hypotheses

Write | Read | Educators

Grumble... Applaud... Please give us your feedback!

- Research Hypotheses »

- Types of Research Hypotheses »

Directional Hypothesis Statement

Ai generator.

Grasping the intricacies of a directional hypothesis is a stepping stone in advanced research. It offers a clear perspective, pointing towards a specific prediction. From meticulously crafted examples to a thesis statement writing guide, and invaluable tips – this segment shines a light on the essence of formulating a precise and informed directional hypothesis. Embark on this enlightening journey and amplify the quality and clarity of your research endeavors.

What is a Directional hypothesis?

A directional hypothesis, often referred to as a one-tailed hypothesis , is a specific type of hypothesis that predicts the direction of the expected relationship between variables. This type of hypothesis is used when researchers have enough preliminary evidence or theoretical foundation to predict the direction of the relationship, rather than merely stating that a relationship exists.

For example, based on previous studies or established theories, a researcher might hypothesize that a specific intervention will lead to an increase (or decrease) in a certain outcome, rather than just hypothesizing that the intervention will have some effect without specifying the direction of that effect.

What is an example of a Directional hypothesis Statement?

“Children exposed to interactive educational software will demonstrate a higher increase in mathematical skills compared to children who receive traditional classroom instruction.” In this statement, the direction of the expected relationship is clear – the use of interactive educational software is predicted to have a positive effect on mathematical skills. You may also be interested in our non directional .

100 Directional Hypothesis Statement Examples

Size: 244 KB

Directional hypotheses are pivotal in streamlining research focus, providing a clear trajectory by anticipating a specific trend or outcome. They’re an embodiment of informed predictions, crafted based on prior knowledge or insightful observations. Discover below a plethora of examples showcasing the essence of these one-tailed, directional assertions.

- Effect of Diet on Weight: Individuals on a high-fiber diet will lose more weight over a month compared to those on a low-fiber diet.

- Physical Activity and Heart Health: Regular aerobic exercise will lead to a more significant reduction in blood pressure than anaerobic exercise.

- Learning Methods: Students taught via hands-on methods will retain information longer than those taught through lectures.

- Music and Productivity: Employees listening to classical music during work hours will demonstrate higher productivity than those listening to pop music.

- Medication Efficacy: Patients administered Drug X will show faster recovery rates from the flu than those given a placebo.

- Sleep and Memory: Individuals sleeping for 8 hours nightly will have better memory recall than those sleeping only 5 hours.

- Training Intensity and Muscle Growth: Athletes undergoing high-intensity training will exhibit more muscle growth than those in low-intensity programs.

- Organic Foods and Health: Consuming organic foods will lead to lower cholesterol levels compared to consuming non-organic foods.

- Stress and Immunity: Individuals exposed to chronic stress will have a lower immune response than those with minimal stress.

- Digital Learning Platforms: Students utilizing digital learning platforms will score higher in standardized tests than those relying solely on textbooks.

- Caffeine and Alertness: People drinking three cups of coffee daily will show higher alertness levels than non-coffee drinkers.

- Therapy Types: Patients undergoing cognitive-behavioral therapy will show greater reductions in depressive symptoms than those in talk therapy.

- E-Books and Reading Speed: Individuals reading from e-books will process content faster than those reading traditional paper books.

- Urban Living and Mental Health: Residents in urban areas will report higher stress levels than those living in rural regions.

- UV Exposure and Skin Health: Consistent exposure to UV rays will lead to faster skin aging compared to limited sun exposure.

- Yoga and Flexibility: Engaging in daily yoga practices will increase flexibility more significantly than bi-weekly practices.

- Meditation and Stress Reduction: Practicing daily meditation will lead to a more substantial decrease in cortisol levels than sporadic meditation.

- Parenting Styles and Child Independence: Children raised with authoritative parenting styles will demonstrate higher levels of independence than those raised with permissive styles.

- Economic Incentives: Workers receiving performance-based bonuses will exhibit higher job satisfaction than those with fixed salaries.

- Sugar Intake and Energy: Consuming high sugar foods will lead to a more rapid energy decline than low-sugar foods.

- Language Acquisition: Children exposed to bilingual environments before age five will develop superior linguistic skills compared to those exposed later in life.

- Herbal Teas and Sleep: Drinking chamomile tea before bedtime will result in a better sleep quality compared to drinking green tea.

- Posture and Back Pain: Individuals who practice regular posture exercises will experience less chronic back pain than those who don’t.

- Air Quality and Respiratory Issues: Residents in cities with high air pollution will report more respiratory issues than those in cities with cleaner air.

- Online Marketing and Sales: Businesses employing targeted online advertising strategies will see a higher increase in sales than those using traditional advertising methods.

- Pet Ownership and Loneliness: Seniors who own pets will report lower levels of loneliness than those who don’t have pets.

- Dietary Supplements and Immunity: Regular intake of vitamin C supplements will lead to fewer instances of common cold than a placebo.

- Technology and Social Skills: Children who spend over five hours daily on electronic devices will exhibit weaker face-to-face social skills than those who spend less than an hour.

- Remote Work and Productivity: Employees working remotely will report higher job satisfaction than those working in a traditional office setting.

- Organic Farming and Soil Health: Farms employing organic methods will have richer soil nutrient content than those using conventional methods.

- Probiotics and Digestive Health: Consuming probiotics daily will lead to improved gut health compared to not consuming any.

- Art Therapy and Trauma Recovery: Individuals undergoing art therapy will show faster emotional recovery from trauma than those using only talk therapy.

- Video Games and Reflexes: Regular gamers will demonstrate quicker reflex actions than non-gamers.

- Forest Bathing and Stress: Engaging in monthly forest bathing sessions will reduce stress levels more significantly than urban recreational activities.

- Vegan Diet and Heart Health: Individuals following a vegan diet will have a lower risk of heart diseases compared to those on omnivorous diets.

- Mindfulness and Anxiety: Practicing mindfulness meditation will result in a more significant reduction in anxiety levels than general relaxation techniques.

- Solar Energy and Cost Efficiency: Over a decade, households using solar energy will report more cost savings than those relying on traditional electricity sources.

- Active Commuting and Fitness Level: People who cycle or walk to work will have better cardiovascular health than those who commute by car.

- Online Learning and Retention: Students who engage in interactive online learning will retain subject matter better than those using passive video lectures.

- Gardening and Mental Wellbeing: Engaging in regular gardening activities will lead to improved mental well-being compared to non-gardening related hobbies.

- Music Therapy and Memory: Alzheimer’s patients exposed to regular music therapy sessions will display better memory retention than those who aren’t.

- Organic Foods and Allergies: Individuals consuming primarily organic foods will report fewer food allergies compared to those consuming non-organic foods.

- Class Size and Learning Efficiency: Students in smaller class sizes will demonstrate higher academic achievements than those in larger classes.

- Sports and Leadership Skills: Teenagers engaged in team sports will develop stronger leadership skills than those engaged in solitary activities.

- Virtual Reality and Pain Management: Patients using virtual reality as a distraction method during minor surgical procedures will report lower pain levels than those using traditional methods.

- Recycling and Environmental Awareness: Communities with mandatory recycling programs will demonstrate higher environmental awareness than those without such programs.

- Acupuncture and Migraine Relief: Migraine sufferers receiving regular acupuncture treatments will experience fewer episodes than those relying only on medication.

- Urban Green Spaces and Mental Health: Residents in cities with ample green spaces will show lower rates of depression compared to cities predominantly built-up.

- Aquatic Exercises and Joint Health: Individuals with arthritis participating in aquatic exercises will report greater joint mobility than those who do land-based exercises.

- E-books and Reading Comprehension: Students using e-books for study will demonstrate similar reading comprehension levels as those using traditional textbooks.

- Financial Literacy Programs and Debt Management: Adults who attended financial literacy programs in school will manage their debts more effectively than those who didn’t.

- Play-based Learning and Creativity: Children educated through play-based learning methods will exhibit higher creativity levels than those in a strictly academic environment.

- Caffeine Consumption and Cognitive Function: Moderate daily caffeine consumption will lead to improved cognitive function compared to high or no caffeine intake.

- Vegetable Intake and Skin Health: Individuals consuming a diet rich in colorful vegetables will have healthier skin compared to those with minimal vegetable intake.

- Physical Activity and Bone Density: Post-menopausal women engaging in weight-bearing exercises will maintain better bone density than those who don’t.

- Intermittent Fasting and Metabolism: Individuals practicing intermittent fasting will demonstrate a more efficient metabolism rate than those on regular diets.

- Public Transport and Air Quality: Cities with extensive public transport systems will have better air quality than cities primarily reliant on individual car use.

- Sleep Duration and Immunity: Adults sleeping between 7-9 hours nightly will have stronger immune responses than those sleeping less or more than this range.

- Hands-on Learning and Skill Retention: Students taught through hands-on practical methods will retain technical skills better than those taught purely theoretically.

- Nature Exposure and Concentration: Regular breaks involving nature exposure during work will result in higher concentration levels than indoor breaks.

- Yoga and Stress Reduction: Individuals practicing daily yoga sessions will experience a more significant reduction in stress levels compared to non-practitioners.

- Pet Ownership and Loneliness: People who own pets, especially dogs or cats, will report lower feelings of loneliness than those without pets.

- Bilingualism and Cognitive Flexibility: Individuals who are bilingual will exhibit higher cognitive flexibility compared to those who speak only one language.

- Green Tea and Weight Loss: Regular consumption of green tea will result in a higher rate of weight loss than those who consume other beverages.

- Plant-based Diets and Heart Health: Individuals following a plant-based diet will show a reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases compared to those on omnivorous diets.

- Forest Bathing and Mental Wellbeing: People who frequently engage in forest bathing or nature walks will demonstrate improved mental wellbeing than those who don’t.

- Online Learning and Independence: Students who predominantly learn through online platforms will develop stronger independent study habits than those in traditional classroom settings.

- Gardening and Life Satisfaction: Individuals engaged in regular gardening will report higher life satisfaction scores than non-gardeners.

- Video Games and Reflexes: People who play action video games frequently will exhibit quicker reflexes than non-gamers.

- Daily Meditation and Anxiety Levels: Individuals who practice daily meditation sessions will experience reduced anxiety levels compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Volunteering and Self-esteem: Regular volunteers will have higher self-esteem and a more positive outlook than those who don’t volunteer.

- Art Therapy and Emotional Expression: Individuals undergoing art therapy will exhibit a broader range of emotional expression than those undergoing traditional counseling.

- Morning Sunlight and Sleep Patterns: Exposure to morning sunlight will result in better nighttime sleep quality than exposure to late afternoon sunlight.

- Probiotics and Digestive Health: Regular intake of probiotics will lead to improved gut health and fewer digestive issues than those not consuming probiotics.

- Digital Detox and Social Skills: Individuals who frequently engage in digital detoxes will develop better face-to-face social skills than constant device users.

- Physical Libraries and Reading Habits: Students with access to physical libraries will exhibit more consistent reading habits than those relying solely on digital sources.

- Public Speaking Training and Confidence: Individuals who undergo public speaking training will express higher confidence levels in various social scenarios than those who don’t.

- Music Lessons and Mathematical Abilities: Children who take music lessons, especially in instruments like the piano, will show improved mathematical abilities compared to non-musical peers.

- Dance and Coordination: Engaging in dance classes will lead to better physical coordination and balance than other forms of exercise.

- Home Cooking and Nutritional Intake: Individuals who predominantly consume home-cooked meals will have a more balanced nutritional intake than those relying on take-out or restaurant meals.

- Organic Foods and Health Outcomes: Individuals consuming predominantly organic foods will exhibit fewer health issues related to preservatives and pesticides than those consuming conventionally grown foods.

- Podcast Consumption and Listening Skills: People who regularly listen to podcasts will demonstrate better active listening skills compared to those who rarely or never listen to podcasts.

- Urban Farming and Community Engagement: Urban areas with community farming initiatives will experience higher levels of community engagement and social interaction than areas without such initiatives.

- Mindfulness Practices and Emotional Regulation: Individuals practicing mindfulness techniques, like deep breathing or body scans, will manage their emotional responses better than those not practicing mindfulness.

- E-books and Reading Speed: People who primarily read e-books will exhibit a faster reading speed compared to those reading printed books.

- Aerobic Exercises and Endurance: Engaging in regular aerobic exercises will lead to higher endurance levels compared to anaerobic exercises.

- Digital Note-taking and Information Retention: Students who use digital platforms for note-taking will retain and recall information less effectively than those taking handwritten notes.

- Cycling to Work and Cardiovascular Health: Individuals who cycle to work will have better cardiovascular health than those who commute using motorized transportation.

- Active Learning Techniques and Academic Performance: Students exposed to active learning strategies will perform better academically than students in traditional lecture-based settings.

- Ergonomic Workspaces and Physical Discomfort: Workers who use ergonomic office furniture will report fewer musculoskeletal problems than those using conventional office furniture.

- Reforestation Initiatives and Air Quality: Areas with proactive reforestation initiatives will have significantly better air quality than areas without such efforts.

- Mediterranean Diet and Lifespan: People following a Mediterranean diet will generally have a longer lifespan compared to those following Western diets.

- Virtual Reality Training and Skill Acquisition: Individuals trained using virtual reality platforms will acquire new skills more rapidly than those trained using traditional methods.

- Solar Energy Adoption and Electricity Bills: Households that adopt solar energy solutions will experience lower monthly electricity bills than those relying solely on grid electricity.

- Journaling and Stress Reduction: Regular journaling will lead to a more significant reduction in perceived stress levels than non-journaling practices.

- Noise-cancelling Headphones and Productivity: Workers using noise-cancelling headphones in open office environments will show higher productivity levels than those not using such headphones.

- Early Birds and Task Efficiency: Individuals who start their day early, or “early birds”, will generally be more efficient in completing tasks than night owls.

- Coding Bootcamps and Job Placement: Graduates from coding bootcamps will find job placements more rapidly than those with only traditional computer science degrees.

- Plant-based Milks and Lactose Intolerance: Consuming plant-based milks, such as almond or oat milk, will cause fewer digestive problems for lactose-intolerant individuals than cow’s milk.

- Sensory Deprivation Tanks and Creativity: Regular sessions in sensory deprivation tanks will lead to heightened creativity levels compared to traditional relaxation methods.

Directional Hypothesis Statement Examples for Psychology

In the realm of psychology, directional psychology hypothesis are valuable as they specifically predict the nature and direction of a relationship or effect. These statements make pointed predictions about expected outcomes in psychological studies, paving the way for focused investigations.

- Emotion Regulation Techniques: Individuals trained in emotion regulation techniques will exhibit lower levels of anxiety than those untrained.

- Positive Reinforcement in Learning: Children exposed to positive reinforcement will exhibit faster learning rates than those exposed to negative reinforcement.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Depression: Patients undergoing cognitive-behavioral therapy will show more significant improvements in depressive symptoms than those using other therapeutic methods.

- Social Media Use and Self-esteem: Adolescents with higher social media usage will report lower self-esteem than their less active counterparts.

- Mindfulness Meditation and Attention Span: Regular practitioners of mindfulness meditation will have longer attention spans than non-practitioners.

- Childhood Trauma and Adult Relationships: Individuals who experienced trauma in childhood will display more attachment issues in adult romantic relationships than those without such experiences.

- Group Therapy and Social Skills: Individuals attending group therapy will demonstrate improved social skills compared to those receiving individual therapy.

- Extrinsic Motivation and Task Performance: Students driven by extrinsic motivation will have lower task persistence than those driven by intrinsic motivation.

- Visual Imagery and Memory Retention: Participants using visual imagery techniques will recall lists of items more effectively than those using rote memorization.

- Parenting Styles and Adolescent Rebellion: Adolescents raised with authoritarian parenting styles will show higher levels of rebellion than those raised with permissive styles.

Directional Hypothesis Statement Examples for Research

In research, a directional research hypothesis narrows down the prediction to a specific direction of the effect. These hypotheses can serve various fields, guiding researchers toward certain anticipated outcomes, making the study’s goal clearer.

- Online Learning Platforms and Student Engagement: Students using interactive online learning platforms will have higher engagement levels than those using traditional online formats.

- Work from Home and Employee Productivity: Employees working from home will report higher job satisfaction but slightly reduced productivity compared to office-going employees.

- Green Spaces and Urban Well-being: Urban areas with more green spaces will have residents reporting higher well-being scores than areas dominated by concrete.

- Dietary Fiber Intake and Digestive Health: Individuals consuming diets rich in fiber will have fewer digestive issues than those on low-fiber diets.

- Public Transportation and Air Quality: Cities that invest more in public transportation will experience better air quality than cities reliant on individual car usage.

- Gamification and Learning Outcomes: Educational modules that incorporate gamification will yield better learning outcomes than traditional modules.

- Open Source Software and System Security: Systems using open-source software will encounter fewer security breaches than those using proprietary software.

- Organic Farming and Soil Health: Farmlands practicing organic farming methods will have richer soil quality than conventionally farmed lands.

- Renewable Energy Sources and Power Grid Stability: Power grids utilizing a higher percentage of renewable energy sources will experience fewer outages than those predominantly using fossil fuels.

- Artificial Sweeteners and Weight Gain: Regular consumers of artificial sweeteners will not necessarily exhibit lower weight gain compared to consumers of natural sugars.

Directional Hypothesis Statement Examples for Correlation Study

Correlation studies evaluate the relationship between two or more variables. Directional hypotheses in correlation studies anticipate a specific type of association – either positive, negative, or neutral.

- Physical Activity and Mental Health: There will be a positive correlation between regular physical activity levels and self-reported mental well-being.

- Sedentary Lifestyle and Cardiovascular Issues: An increased sedentary lifestyle duration will correlate positively with cardiovascular health issues.

- Reading Habits and Vocabulary Size: There will be a positive correlation between the frequency of reading and the breadth of an individual’s vocabulary.

- Fast Food Consumption and Health Risks: A higher frequency of fast food consumption will correlate with increased health risks, such as obesity or high blood pressure.

- Financial Literacy and Debt Management: Individuals with higher financial literacy will have a negative correlation with unmanaged debts.

- Sleep Duration and Cognitive Performance: There will be a positive correlation between the optimal sleep duration (7-9 hours) and cognitive performance in adults.