Broken Windows Theory of Criminology

Charlotte Ruhl

Research Assistant & Psychology Graduate

BA (Hons) Psychology, Harvard University

Charlotte Ruhl, a psychology graduate from Harvard College, boasts over six years of research experience in clinical and social psychology. During her tenure at Harvard, she contributed to the Decision Science Lab, administering numerous studies in behavioral economics and social psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

The Broken Windows Theory of Criminology suggests that visible signs of disorder and neglect, such as broken windows or graffiti, can encourage further crime and anti-social behavior in an area, as they signal a lack of order and law enforcement.

Key Takeaways

- The Broken Windows theory, first studied by Philip Zimbardo and introduced by George Kelling and James Wilson, holds that visible indicators of disorder, such as vandalism, loitering, and broken windows, invite criminal activity and should be prosecuted.

- This form of policing has been tested in several real-world settings. It was heavily enforced in the mid-1990s under New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, and Albuquerque, New Mexico, Lowell, Massachusetts, and the Netherlands later experimented with this theory.

- Although initial research proved to be promising, this theory has been met with several criticisms. Specifically, many scholars point to the fact that there is no clear causal relationship between lack of order and crime. Rather, crime going down when order goes up is merely a coincidental correlation.

- Additionally, this theory has opened the doors for racial and class bias, especially in the form of stop and frisk.

The United States has the largest prison population in the world and the highest per-capita incarceration rate. In 2016, 2.3 million people were incarcerated, despite a massive decline in both violent and property crimes (Morgan & Kena, 2019).

These statistics provide some insight into why crime regulation and mass incarceration are such hot topics today, and many scholars, lawyers, and politicians have devised theories and strategies to try to promote safety within society.

One such model is broken windows policing, which was first brought to light by American psychologist Philip Zimbardo (famous for his Stanford Prison Experiment) and further publicized by James Wilson and George Kelling. Since its inception, this theory has been both widely used and widely criticized.

What Is the Broken Windows Theory?

The broken windows theory states that any visible signs of crime and civil disorder, such as broken windows (hence, the name of the theory), vandalism, loitering, public drinking, jaywalking, and transportation fare evasion, create an urban environment that promotes even more crime and disorder (Wilson & Kelling, 1982).

As such, policing these misdemeanors will help create an ordered and lawful society in which all citizens feel safe and crime rates, including violent crime rates, are low.

Broken windows policing tries to regulate low-level crime to prevent widespread disorder from occurring. If these small crimes are greatly reduced, then neighborhoods will appear to be more cared for.

The hope is that if these visible displays of disorder and neglect are reduced, violent crimes might go down too, leading to an overall reduction in crime and an increase in public safety.

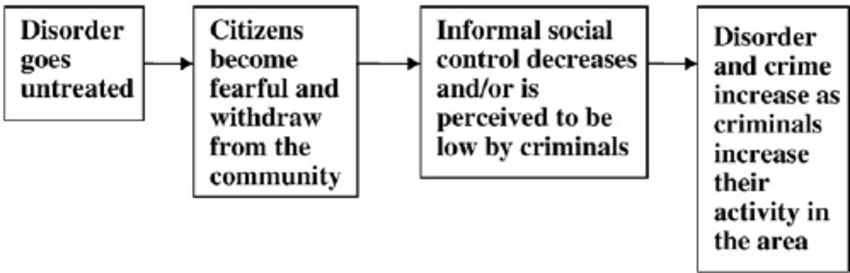

Source: Hinkle, J. C., & Weisburd, D. (2008). The irony of broken windows policing: A micro-place study of the relationship between disorder, focused police crackdowns and fear of crime. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36(6), 503-512.

Academics justify broken windows policing from a theoretical standpoint because of three specific factors that help explain why the state of the urban environment might affect crime levels:

- social norms and conformity;

- the presence or lack of routine monitoring;

- social signaling and signal crime.

In a typical urban environment, social norms and monitoring are not clearly known. As a result, individuals will look for certain signs and signals that provide both insight into the social norms of the area as well as the risk of getting caught violating those norms.

Those who support the broken windows theory argue that one of those signals is the area’s general appearance. In other words, an ordered environment, one that is safe and has very little lawlessness, sends the message that this neighborhood is routinely monitored and criminal acts are not tolerated.

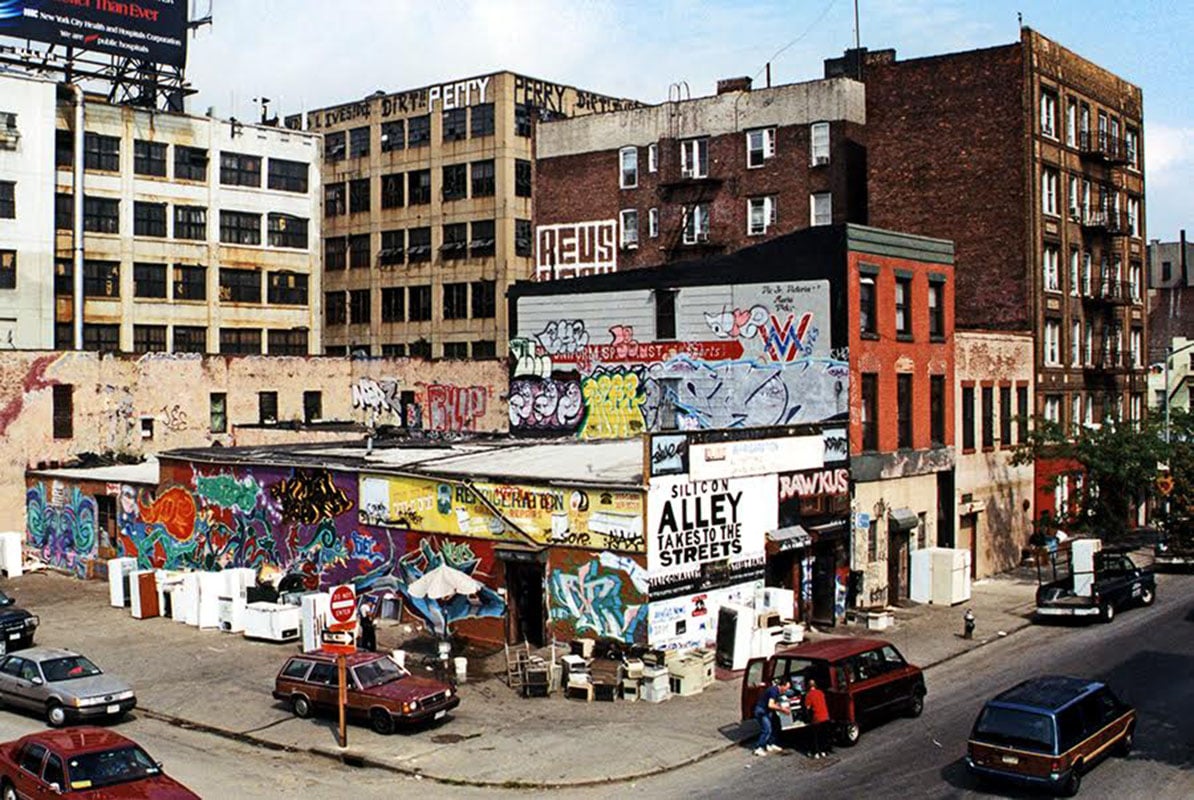

On the other hand, a disordered environment, one that is not as safe and contains visible acts of lawlessness (such as broken windows, graffiti, and litter), sends the message that this neighborhood is not routinely monitored and individuals would be much more likely to get away with committing a crime.

With a decreased likelihood of detection, individuals would be much more inclined to engage in criminal behavior, both violent and nonviolent, in this type of area.

As you might be able to tell, a major assumption that this theory makes is that an environment’s landscape communicates to its residents in some way.

For example, proponents of this theory would argue that a broken window signals to potential criminals that a community is unable to defend itself against an uptick in criminal activity. It is not the literal broken window that is a direct cause for concern, but more so the figurative meaning that is ascribed to this situation.

It symbolizes a vulnerable and disjointed community that cannot handle crime – opening the doors to all kinds of unwanted activity to occur.

In neighborhoods that do have a strong sense of social cohesion among their residents, these broken windows are fixed (both literally and figuratively), giving these areas a sense of control over their communities.

By fixing these windows, undesired individuals and behaviors are removed, allowing civilians to feel safer (Herbert & Brown, 2006).

However, in environments in which these broken windows are left unfixed, residents no longer see their communities as tight-knit, safe spaces and will avoid spending time in communal spaces (in parks, at local stores, on the street blocks) so as to avoid violent attacks from strangers.

Additionally, when these broken windows are not fixed, it also symbolizes a lack of informal social control. Informal social control refers to the actions that regulate behavior, such as conforming to social norms and intervening as a bystander when a crime is committed, that are independent of the law.

Informal social control is important to help reduce unruly behavior. Scholars argue that, under certain circumstances, informal social control is more effective than laws.

And some will even go so far as to say that nonresidential spaces, such as corner stores and businesses, have a responsibility to actually maintain this informal social control by way of constant surveillance and supervision.

One such scholar is Jane Jacobs, a Canadian-American author and journalist who believed sidewalks were a crucial vehicle for promoting public safety.

Jacobs can be considered one of the original pioneers of the broken windows theory. One of her most famous books, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, describes how local businesses and stores provide a necessary sense of having “eyes on the street,” which promotes safety and helps to regulate crime (Jacobs, 1961).

Although the idea that community involvement, from both residents and non-residents, can make a big difference in how safe a neighborhood is perceived to be, Wilson and Keeling argue that the police are the key to maintaining order.

As major proponents of broken windows policing, they hold that formal social control, in addition to informal social control, is crucial for actually regulating crime.

Although different people have different approaches to the implementation of broken windows (i.e., cleaning up the environment and informal social control vs. an increase in policing misdemeanor crimes), the end goal is the same: crime reduction.

This idea, which largely serves as the backbone of the broken windows theory, was first introduced by Philip Zimbardo.

Examples of Broken Windows Policing

1969: philip zimbardo’s introduction of broken windows in nyc and la.

In 1969, Stanford psychologist Philip Zimbardo ran a social experiment in which he abandoned two cars that had no license plates and the hoods up in very different locations.

The first was a predominantly poor, high-crime neighborhood in the Bronx, and the second was a fairly affluent area of Palo Alto, California. He then observed two very different outcomes.

After just ten minutes, the car in the Bronx was attacked and vandalized. A family first approached the vehicle and removed the radiator and battery. Within the first twenty-four hours after Zimbardo left the car, everything valuable had been stripped and removed from the car.

Afterward, random acts of destruction began – the windows were smashed, seats were ripped up, and the car began to serve as a playground for children in the community.

On the contrary, the car that was left in Palo Alto remained untouched for more than a week before Zimbardo eventually went up to it and smashed the vehicle with a sledgehammer.

Only after he had done this did other people join the destruction of the car (Zimbardo, 1969). Zimbardo concluded that something that is clearly abandoned and neglected can become a target for vandalism.

But Kelling and Wilson extended this finding when they introduced the concept of broken windows policing in the early 1980s.

This initial study cascaded into a body of research and policy that demonstrated how in areas such as the Bronx, where theft, destruction, and abandonment are more common, vandalism would occur much faster because there are no opposing forces to this type of behavior.

As a result, such forces, primarily the police, are needed to intervene and reduce these types of behavior and remove such indicators of disorder.

1982: Kelling and Wilson’s Follow-Up Article

Thirteen years after Zimbardo’s study was published, criminologists George Kelling and James Wilson published an article in The Atlantic that applied Zimbardo’s findings to entire communities.

Kelling argues that Zimbardo’s findings were not unique to the Bronx and Palo Alto areas. Rather, he claims that, regardless of the neighborhood, a ripple effect can occur once disorder begins as things get extremely out of hand and control becomes increasingly hard to maintain.

The article introduces the broader idea that now lies at the heart of the broken windows theory: a broken window, or other signs of disorder, such as loitering, graffiti, litter, or drug use, can send the message that a neighborhood is uncared for, sending an open invitation for crime to continue to occur, even violent crimes.

The solution, according to Kelling and Wilson and many other proponents of this theory, is to target these very low-level crimes, restore order to the neighborhood, and prevent more violent crimes from happening.

A strengthened and ordered community is equipped to fight and deter crime (because a sense of order creates the perception that crimes go easily detected). As such, it is necessary for police departments to focus on cleaning up the streets as opposed to putting all of their energy into fighting high-level crimes.

In addition to Zimbardo’s 1969 study, Kelling and Wilson’s article was also largely inspired by New Jersey’s “Safe and Clean Neighborhoods Program” that was implemented in the mid-1970s.

As part of the program, police officers were taken out of their patrol cars and were asked to patrol on foot. The aim of this approach was to make citizens feel more secure in their neighborhoods.

Although crime was not reduced as a result, residents took fewer steps to protect themselves from crime (such as locking their doors). Reducing fear is a huge goal of broken-windows policing.

As Kelling and Wilson state in their article, the fear of being bothered by disorderly people (such as drunks, rowdy teens, or loiterers) is enough to motivate them to withdraw from the community.

But if we can find a way to make people feel less fear (namely by reducing low-level crimes), then they will be more involved in their communities, creating a higher degree of informal social control and deterring all forms of criminal activity.

Although Kelling and Wilson’s article was largely theoretical, the practice of broken windows policing was implemented in the early 1990s under New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani. And Kelling himself was there to play a crucial role.

Early 1990s: Bratton and Giuliani’s implementation in NYC

In 1985, the New York City Transit Authority hired George Kelling as a consultant, and he was also later hired by both the Boston and Los Angeles police departments to provide advice on the most effective method for policing (Fagan & Davies, 2000).

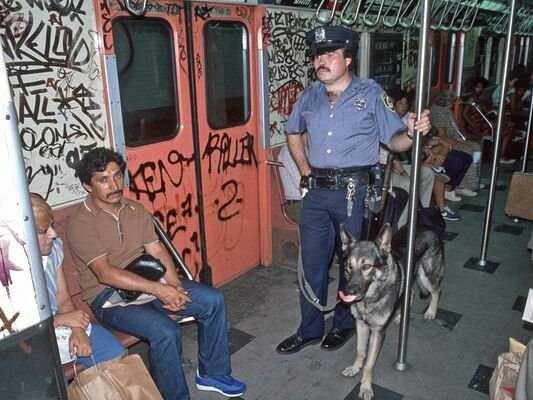

Five years later, in 1990, William J. Bratton became the head of the New York City Transit Police. In his role, Bratton cracked down on fare evasion and implemented faster methods to process those who were arrested.

He attributed a lot of his decisions as head of the transit police to Kelling’s work. Bratton was just the first to begin to implement such measures, but once Rudy Giuliani was elected as mayor in 1993, tactics to reduce crime began to really take off (Vedantam et al., 2016).

Together, Giuliani and Bratton first focused on cleaning up the subway system, where Bratton’s area of expertise lay. They sent hundreds of police officers into subway stations throughout the city to catch anyone who was jumping the turnstiles and evading the fair.

And this was just the beginning.

All throughout the 90s, Giuliani increased misdemeanor arrests in all pockets of the city. They arrested numerous people for smoking marijuana in public, spraying graffiti on walls, selling cigarettes, and they shut down many of the city’s night spots for illegal dancing.

Conveniently, during this time, crime was also falling in the city and the murder rate was rapidly decreasing, earning Giuliani re-election in 1997 (Vedantam et al., 2016).

To further support the outpouring success of this new approach to regulating crime, George Kelling ran a follow-up study on the efficacy of broken windows policing and found that in neighborhoods where there was a stark increase in misdemeanor arrests (evidence of broken windows policing), there was also a sharp decline in crime (Kelling & Sousa, 2001).

Because this seemed like an incredibly successful mode, cities around the world began to adopt this approach.

Late 1990s: Albuquerque’s Safe Streets Program

In Albuquerque, New Mexico, a Safe Streets Program was implemented to deter and reduce unsafe driving and crime rates by increasing surveillance in these areas.

Specifically, the traffic enforcement program influenced saturation patrols (that operated over a large geographic area), sobriety checkpoints, follow-up patrols, and freeway speed enforcement.

The effectiveness of this program was analyzed in a study done by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (Stuser, 2001).

Results demonstrated that both Part I crimes, including homicide, forcible rape, robbery, and theft, and Part II crimes, such as sex offenses, kidnapping, stolen property, and fraud, experienced a total decline of 5% during the 1996-1997 calendar year in which this program was implemented.

Additionally, this program resulted in a 9% decline in both robbery and burglary, a 10% decline in assault, a 17% decline in kidnapping, a 29% decline in homicide, and a 36% decline in arson.

With these promising statistics came a 14% increase in arrests. Thus, the researchers concluded that traffic enforcement programs can deter criminal activity. This approach was initially inspired by both Zimbardo’s and Kelling and Wilson’s work on broken windows and provides evidence that when policing and surveillance increase, crime rates go down.

2005: Lowell, Massachusetts

Back on the east coast, Harvard University and Suffolk University researchers worked with local police officers to pinpoint 34 different crime hotspots in Lowell, Massachusetts. In half of these areas, local police officers and authorities cleaned up trash from the streets, fixed streetlights, expanded aid for the homeless, and made more misdemeanor arrests.

There was no change made in the other half of the areas (Johnson, 2009).

The researchers found that in areas in which police service was changed, there was a 20% reduction in calls to the police. And because the researchers implemented different ways of changing the city’s landscape, from cleaning the physical environment to increasing arrests, they were able to compare the effectiveness of these various approaches.

Although many proponents of the broken windows theory argue that increasing policing and arrests is the solution to reducing crime, as the previous study in Albuquerque illustrates. Others insist that more arrests do not solve the problem but rather changing the physical landscape should be the desired means to an end.

And this is exactly what Brenda Bond of Suffolk University and Anthony Braga of Harvard Kennedy’s School of Government found. Cleaning up the physical environment was revealed to be very effective, misdemeanor arrests were less so, and increasing social services had no impact.

This study provided strong evidence for the effectiveness of the broken windows theory in reducing crime by decreasing disorder, specifically in the context of cleaning up the physical and visible neighborhood (Braga & Bond, 2008).

2007: Netherlands

The United States is not the only country that sought to implement the broken windows ideology. Beginning in 2007, researchers from the University of Groningen ran several studies that looked at whether existing visible disorder increased crimes such as theft and littering.

Similar to the Lowell experiment, where half of the areas were ordered and the other half disorders, Keizer and colleagues arranged several urban areas in two different ways at two different times. In one condition, the area was ordered, with an absence of graffiti and littering, but in the other condition, there was visible evidence for disorder.

The team found that in disorderly environments, people were much more likely to litter, take shortcuts through a fenced-off area, and take an envelope out of an open mailbox that was clearly labeled to contain five Euros (Keizer et al., 2008).

This study provides additional support for the effect perceived order can have on the likelihood of criminal activity. But this broken windows theory is not restricted to the criminal legal setting.

2008: Tokyo, Japan

The local government of Adachi Ward, Tokyo, which once had Tokyo’s highest crime rates, introduced the “Beautiful Windows Movement” in 2008 (Hino & Chronopoulos, 2021).

The intervention was twofold. The program, on one hand, drawing on the broken windows theory, promoted policing to prevent minor crimes and disorder. On the other hand, in partnership with citizen volunteers, the authorities launched a project to make Adachi Ward literally beautiful.

Following 11 years of implementation, the reduction in crime was undeniable. Felony had dropped from 122 in 2008 to 35 in 2019, burglary from 104 to 24, and bicycle theft from 93 to 45.

This Japanese case study seemed to further highlight the advantages associated with translating the broken widow theory into both aggressive policing and landscape altering.

Other Domains Relevant to Broken Windows

There are several other fields in which the broken windows theory is implicated. The first is real estate. Broken windows (and other similar signs of disorder) can indicate low real estate value, thus deterring investors (Hunt, 2015).

As such, some recommend that the real estate industry adopt the broken windows theory to increase value in an apartment, house, or even an entire neighborhood. They might increase in value by fixing windows and cleaning up the area (Harcourt & Ludwig, 2006).

Consequently, this might lead to gentrification – the process by which poorer urban landscapes are changed as wealthier individuals move in.

Although many would argue that this might help the economy and provide a safe area for people to live, this often displaces low-income families and prevents them from moving into areas they previously could not afford.

This is a very salient topic in the United States as many areas are becoming gentrified, and regardless of whether you support this process, it is important to understand how the real estate industry is directly connected to the broken windows theory.

Another area that broken windows are related to is education. Here, the broken windows theory is used to promote order in the classroom. In this setting, the students replace those who engage in criminal activity.

The idea is that students are signaled by disorder or others breaking classroom rules and take this as an open invitation to further contribute to the disorder.

As such, many schools rely on strict regulations such as punishing curse words and speaking out of turn, forcing strict dress and behavioral codes, and enforcing specific classroom etiquette.

Similar to the previous studies, from 2004 to 2006, Stephen Plank and colleagues conducted a study that measured the relationship between the physical appearance of mid-Atlantic schools and student behavior.

They determined that variables such as fear, social order, and informal social control were statistically significantly associated with the physical conditions of the school setting.

Thus, the researchers urged educators to tend to the school’s physical appearance to help promote a productive classroom environment in which students are less likely to propagate disordered behavior (Plank et al., 2009).

Despite there being a large body of research that seems to support the broken windows theory, this theory does not come without its stark criticisms, especially in the past few years.

Major Criticisms

At the turn of the 21st century, the rhetoric surrounding broken windows drastically shifted from praise to criticism. Scholars scrutinized conclusions that were drawn, questioned empirical methodologies, and feared that this theory was morphing into a vehicle for discrimination.

Misinterpreting the Relationship Between Disorder and Crime

A major criticism of this theory argues that it misinterprets the relationship between disorder and crime by drawing a causal chain between the two.

Instead, some researchers argue that a third factor, collective efficacy, or the cohesion among residents combined with shared expectations for the social control of public space, is the causal agent explaining crime rates (Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999).

A 2019 meta-analysis that looked at 300 studies revealed that disorder in a neighborhood does not directly cause its residents to commit more crimes (O’Brien et al., 2019).

The researchers examined studies that tested to what extent disorder led people to commit crimes, made them feel more fearful of crime in their neighborhoods, and affected their perceptions of their neighborhoods.

In addition to drawing out several methodological flaws in the hundreds of studies that were included in the analysis, O’Brien and colleagues found no evidence that the disorder and crime are causally linked.

Similarly, in 2003, David Thatcher published a paper in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology arguing that broken windows policing was not as effective as it appeared to be on the surface.

Crime rates dropping in areas such as New York City were not a direct result of this new law enforcement tactic. Those who believed this were simply conflating correlation and causality.

Rather, Thatcher claims, lower crime rates were the result of various other factors, none of which fell into the category of ramping up misdemeanor arrests (Thatcher, 2003).

In terms of the specific factors that were actually playing a role in the decrease in crime, some scholars point to the waning of the cocaine epidemic and strict enforcement of the Rockefeller drug laws that contributed to lower crime rates (Metcalf, 2006).

Other explanations include trends such as New York City’s economic boom in the late 1990s that helped directly contribute to the decrease of crime much more so than enacting the broken windows policy (Sridhar, 2006).

Additionally, cities that did not implement broken windows also saw a decrease in crime (Harcourt, 2009), and similarly, crime rates weren’t decreasing in other cities that adopted the broken windows policy (Sridhar, 2006).

Specifically, Bernard Harcourt and Jens Ludwig examined the Department of Housing and Urban Development program that placed inner-city project residents into housing in more orderly neighborhoods.

Contrary to the broken windows theory, which would predict that these tenants would now commit fewer crimes once relocated into more ordered neighborhoods, they found that these individuals continued to commit crimes at the same rate.

This study provides clear evidence why broken windows may not be the causal agent in crime reduction (Harcourt & Ludwig, 2006).

Falsely Assuming Why Crimes Are Committed

The broken windows theory also assumes that in more orderly neighborhoods, there is more informal social control. As a result, people understand that there is a greater likelihood of being caught committing a crime, so they shy away from engaging in such activity.

However, people don’t only commit crimes because of the perceived likelihood of detection. Rather, many individuals who commit crimes do so because of factors unrelated to or without considering the repercussions.

Poverty, social pressure, mental illness, and more are often driving factors that help explain why a person might commit a crime, especially a misdemeanor such as theft or loitering.

Resulting in Racial and Class Bias

One of the leading criticisms of the broken windows theory is that it leads to both racial and class bias. By giving the police broad discretion to define disorder and determine who engages in disorderly acts allows them to freely criminalize communities of color and groups that are socioeconomically disadvantaged (Roberts, 1998).

For example, Sampson and Raudenbush found that in two neighborhoods with equal amounts of graffiti and litter, people saw more disorder in neighborhoods with more African Americans.

The researchers found that individuals associate African Americans and other minority groups with concepts of crime and disorder more so than their white counterparts (Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004).

This can lead to unfair policing in areas that are predominantly people of color. In addition, those who suffer from financial instability and may be of minority status are more likely to commit crimes in the first place.

Thus, they are simply being punished for being poor as opposed to being given resources to assist them. Further, many acts that are actually legal but are deemed disorderly by police officers are targeted in public settings but aren’t targeted when the same acts are conducted in private settings.

As a result, those who don’t have access to private spaces, such as homeless people, are unnecessarily criminalized.

It follows then that by policing these small misdemeanors, or oftentimes actions that aren’t even crimes at all, police departments are fighting poverty crimes as opposed to fighting to provide individuals with the resources that will make crime no longer a necessity.

Morphing into Stop and Frisk

Stop and frisk, a brief non-intrusive police stop of a suspect is an extremely controversial approach to policing. But critics of the broken windows theory argue that it has morphed into this program.

With broken-windows policing, officers have too much discretion when determining who is engaging in criminal activity and will search people for drugs and weapons without probable cause.

However, this method is highly unsuccessful. In 2008, the police made nearly 250,000 stops in New York, but only one-fifteenth of one percent of those stops resulted in finding a gun (Vedantam et al., 2016).

And three years later, in 2011, more than 685,000 people were stopped in New York. Of those, nine out of ten were found to be completely innocent (Dunn & Shames, 2020).

Thus, not only does this give officers free reins to stop and frisk minority populations at disproportionately high levels, but it also is not effective in drawing out crime.

Although broken windows policing might seem effective from a theoretical perspective, major valid criticisms put the practical application of this theory into question.

Given its controversial nature, broken windows policing is not explicitly used today to regulate crime in most major cities. However, there are still traces of this theory that remain.

Cities such as Ferguson, Missouri, are heavily policed and the city issues thousands of warrants a year on broken window types of crimes – from parking infractions to traffic violations.

And the racial and class biases that result from such an approach to law enforcement have definitely not disappeared.

Crime regulation is not easy, but the broken windows theory provides an approach to reducing offenses and maintaining order in society.

What is the broken glass principle?

The broken glass principle, also known as the Broken Windows Theory, posits that visible signs of disorder, like broken glass, can foster further crime and anti-social behavior by signaling a lack of regulation and community care in an area.

How does social context affect crime according to the broken windows theory?

The Broken Windows Theory proposes that the social context, specifically visible signs of disorder like vandalism or littering, can encourage further crime.

It suggests that these signs indicate a lack of community control and care, which can foster a climate of disregard for laws and social norms, leading to more severe crimes over time.

How did broken windows theory change policing?

The Broken Windows Theory influenced policing by promoting proactive attention to minor crimes and maintaining urban environments.

It led to strategies like “zero-tolerance” or “quality-of-life” policing, focusing on reducing visible signs of disorder to prevent more serious crime.

Braga, A. A., & Bond, B. J. (2008). Policing crime and disorder hot spots: A randomized controlled trial. Criminology, 46(3), 577-607.

Dunn, C., & Shames, M. (2020). Stop-and-Frisk data . Retrieved from https://www.nyclu.org/en/stop-and-frisk-data

Fagan, J., & Davies, G. (2000). Street stops and broken windows: Terry, race, and disorder in New York City. Fordham Urb. LJ , 28, 457.

Harcourt, B. E. (2009). Illusion of order: The false promise of broken windows policing . Harvard University Press.

Harcourt, B. E., & Ludwig, J. (2006). Broken windows: New evidence from New York City and a five-city social experiment. U. Chi. L. Rev., 73 , 271.

Herbert, S., & Brown, E. (2006). Conceptions of space and crime in the punitive neoliberal city. Antipode, 38 (4), 755-777.

Hunt, B. (2015). “Broken Windows” theory can be applied to real estate regulation- Realty Times. Retrieved from https://realtytimes.com/agentnews/agentadvice/item/40700-20151208-broken-windws-theory-can-be-applied-to-real-estate-regulation

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities . Vintage.

Johnson, C. Y. (2009). Breakthrough on “broken windows.” Boston Globe.

Keizer, K., Lindenberg, S., & Steg, L. (2008). The spreading of disorder. Science, 322 (5908), 1681-1685.

Kelling, G. L., & Sousa, W. H. (2001). Do police matter?: An analysis of the impact of new york city’s police reforms . CCI Center for Civic Innovation at the Manhattan Institute.

Metcalf, S. (2006). Rudy Giuliani, American president? Retrieved from https://slate.com/culture/2006/05/rudy-giuliani-american-president.html

Morgan, R. E., & Kena, G. (2019). Criminal victimization, 2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics , 253043.

O”Brien, D. T., Farrell, C., & Welsh, B. C. (2019). Looking through broken windows: The impact of neighborhood disorder on aggression and fear of crime is an artifact of research design. Annual Review of Criminology, 2 , 53-71.

Plank, S. B., Bradshaw, C. P., & Young, H. (2009). An application of “broken-windows” and related theories to the study of disorder, fear, and collective efficacy in schools. American Journal of Education, 115 (2), 227-247.

Roberts, D. E. (1998). Race, vagueness, and the social meaning of order-maintenance policing. J. Crim. L. & Criminology, 89 , 775.

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1999). Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology, 105 (3), 603-651.

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2004). Seeing disorder: Neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “broken windows”. Social psychology quarterly, 67 (4), 319-342.

Sridhar, C. R. (2006). Broken windows and zero tolerance: Policing urban crimes. Economic and Political Weekly , 1841-1843.

Stuster, J. (2001). Albuquerque police department’s Safe Streets program (No. DOT-HS-809-278). Anacapa Sciences, inc.

Thacher, D. (2003). Order maintenance reconsidered: Moving beyond strong causal reasoning. J. Crim. L. & Criminology, 94 , 381.

Vedantam, S., Benderev, C., Boyle, T., Klahr, R., Penman, M., & Schmidt, J. (2016). How a theory of crime and policing was born, and went terribly wrong . Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2016/11/01/500104506/broken-windows-policing-and-the-origins-of-stop-and-frisk-and-how-it-went-wrong

Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken windows. Atlantic monthly, 249 (3), 29-38.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1969). The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order versus deindividuation, impulse, and chaos. In Nebraska symposium on motivation. University of Nebraska press.

Further Information

- Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken windows. Atlantic monthly, 249(3), 29-38.

- Fagan, J., & Davies, G. (2000). Street stops and broken windows: Terry, race, and disorder in New York City. Fordham Urb. LJ, 28, 457.

- Fagan, J. A., Geller, A., Davies, G., & West, V. (2010). Street stops and broken windows revisited. In Race, ethnicity, and policing (pp. 309-348). New York University Press.

Broken Windows Thesis

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 27 November 2018

- Cite this reference work entry

- Joshua C. Hinkle 5

1187 Accesses

3 Citations

Incivilities thesis ; Order maintenance

Few ideas in criminology have had the type of direct impact on criminal justice policy exhibited by the broken windows thesis. From its inauspicious beginnings in a nine-page article by James Q. Wilson and George Kelling in The Atlantic Monthly , the broken windows thesis has impacted policing strategies around the world. From the “quality of life policing” efforts in New York City (Kelling and Sousa 2001 ) to “Zero Tolerance” policing in England (Dennis and Mallon 1998 ), police agencies around the world have embraced Wilson and Kelling’s idea that focusing on less serious offenses can yield important benefits in terms of community safety and prevention of more serious crime. Despite this broad policy influence, research on the theory itself has been relatively weak and has produced equivocal findings as will be detailed in this entry.

The Broken Windows Model

In a nutshell, the broken windows thesis (Wilson and Kelling 1982 )...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Recommended Reading and References

Bratton WJ, Kelling GL (2006) There are no cracks in the broken windows. Natl Rev Online, February 28.Retrieved from http://www.nationalreview.com/comment/bratton_kelling200602281015.asp

Covington J, Taylor RB (1991) Fear of crime in urban residential neighborhoods: implication of between- and within-neighborhood sources for current models. Sociol Q 32(2):231–249

Google Scholar

Dennis N, Mallon R (1998) Confident policing in Hartlepool. In: Dennis N (ed) Zero tolerance: policing a free society. Institute of Economic Affairs Health and Welfare Unit, London, pp 62–87

Ford JM, Beveridge AA (2004) “Bad” neighborhoods, fast food, “sleazy” businesses, and drug dealers: relationships between the location of licit and illicit businesses in the urban environment. J Drug Issues 34(1):51–76

Garafalo J (1981) The fear of crime: causes and consequences. J Crim Law Criminol 72(2):839–857

Garofalo J, Laub JH (1978) The fear of crime: broadening our perspective. Victimology 3(3–4):242–253

Gault M, Silver E (2008) Spuriousness or mediation? Broken windows according to Sampson and Raudenbush (1999). J Crim Just 36(3):240–243

Hinkle JC (2009) Making sense of broken windows: the relationship between perceptions of disorder, fear of crime, collective efficacy and perceptions of crime. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park

Hunter A (1978) Symbols of incivility: Social disorder and fear of crime in urban neighborhoods. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology, Dallas, TX

Keizer K, Lindenberg S, Steg L (2008) The spreading of disorder. Science 12:1681–1685

Kelling GL, Coles C (1996) Fixing broken windows: restoring order and reducing crime in American cities. Free Press, New York

Kelling GL, Sousa WH (2001) Do police matter? An analysis of the impact of New York City's police reforms (Civic report No., 22). Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, New York

Kelling GL, Pate T, Ferrara A, Utne M, Brown CE (1981) The newark foot patrol experiment. The Police Foundation, Washington, DC

LaGrange RL, Ferraro KP, Supancic M (1992) Perceived risk and fear of crime: role of social and physical incivilities. J Res Crime Delinq 29(3):311–334

Markowitz FE, Bellair PE, Liska AE, Liu J (2001) Extending social disorganization theory: modeling the relationships between cohesion, disorder and fear. Criminology 39(2):293–320

Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (2001) Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology 39(3):517–560

Robinson JB, Lawton BA, Taylor RB, Perkins DD (2003) Multilevel longitudinal impacts of incivilities: fear of crime, expected safety, and block satisfaction. J Quant Criminol 19(3):237–274

Sabol WJ, Coulton CJ, Korbin JE (2004) Building community capacity for violence prevention. J Interpers Violence 19(3):322–340

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (1999) Systematic social observation of public spaces: a new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. Am J Sociol 105(3):603–651

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277(5328):918–924

St. Jean PKB (2007) Pockets of crime: broken windows, collective efficacy, and the criminal point of view. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Taylor RB (2001) Breaking away from broken windows: Baltimore neighborhoods and the nationwide fight against crime, grime, fear, and decline. Westview Press, Boulder

Taylor RB, Shumaker SA (1990) Local crime as a natural hazard: implications for understanding the relationship between disorder and fear of crime. Am J Community Psychol 18(5):619–641

Wilson JQ (1975) Thinking about crime. Basic Books, New York

Wilson JQ, Boland B (1978) The effect of the police on crime. Law Soc Rev 12:367–390

Wilson JQ, Kelling GL (1982) Broken windows: the police and neighborhood safety. Atl Mon 211:29–38

Xu Y, Fiedler ML, Flaming KH (2005) Discovering the impact of community policing: the broken windows thesis, collective efficacy and citizens’ judgment. J Res Crime Delinq 42(2):147–186

Yang S (2007) Causal or merely co-existing: a longitudinal study of disorder and violence at places. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park

Yang S (2010) Assessing the spatial-temporal relationship between disorder and violence. J Quant Criminol 26(1):139–163

Zimbardo PG (1969) The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order versus deindividuation, impulse, and chaos. Nebr Sym Motiv 17:237–307

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology, Georgia State University, 4018, Atlanta, GA, 30302, USA

Joshua C. Hinkle

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joshua C. Hinkle .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement (NSCR), Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Gerben Bruinsma

VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Department of Criminology, Law and Society, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA

David Weisburd

Faculty of Law, The Hebrew University, Mt. Scopus, Jerusalem, Israel

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Hinkle, J.C. (2014). Broken Windows Thesis. In: Bruinsma, G., Weisburd, D. (eds) Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5690-2_14

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5690-2_14

Published : 27 November 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4614-5689-6

Online ISBN : 978-1-4614-5690-2

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Broken windows thesis, quick reference.

A thesis which links disorderly behaviour to fear of crime, the potential for serious crime, and to urban decay in American cities. It is often cited as an example of communitarian ideas informing public policy.

In 1982 political scientist James Wilson and criminologist George Kelling published an article under the title ‘Broken Windows’, arguing that policing in neighbourhoods should be based on a clear understanding of the connection between order-maintenance and crime prevention. In their view the best way to fight crime is to fight the disorder that precedes it. They used the image of broken windows to explain how neighbourhoods might decay into disorder and crime if no one attends to their maintenance: a broken factory window suggests to passers-by that no one is in Charge or cares; in time a few more windows are broken by rock-throwing youths; passers-by begin to think that no one cares about the whole street; soon, only the young and criminals are prepared to use the street; which then attracts prostitution, drug-dealing, and such like; until, in due course, someone is murdered. In this way, small disorders lead to larger disorders, and eventually to serious crimes.

This analysis implies that if disorderly behaviours in public places (including all forms of petty vandalism, begging, vagrancy, and so forth) are controlled then a significant drop in serious crime will follow. Wilson and Kelling therefore argue in favour of ‘community policing’ in neighbourhoods. This means many more officers on foot-patrol and fewer in police cars responding to emergency calls. Law enforcement should be a technique for crime prevention rather than a vehicle for reacting to crime.

These ideas were taken up by the New York Transit Authority, which adopted a policy of zero tolerance towards graffiti on trains, urinating in public, intimidation of commuters, and such like, and dramatically reduced the incidence of serious crime in New York City subways. Similar initiatives have also achieved notable successes in reducing crime-rates and urban decay in many other American cities. Typically these involve some mixture of Neighbourhood Watch programmes, zero tolerance of minor public disorders, a shift towards ‘community-oriented’ (preventive) and away from ‘incident-oriented’ (reactive) policing, police involvement in local youth projects, decentralization of authority to individual police officers, and community involvement in setting priorities for and collaborating with prosecutors, police, probation officers, and other criminal justice officials (see George Kelling and Catherine Coles, Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in our Communities, 1996). See also criminology.

From: broken windows thesis in A Dictionary of Sociology »

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries.

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'broken windows thesis' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 23 December 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|162.248.224.4]

- 162.248.224.4

Character limit 500 /500

- Sociology Questions & Answers

- Sociology Dictionary

- Books, Journals, Papers

- Guides & How To’s

- Life Around The World

- Research Methods

- Functionalism

- Postmodernism

- Social Constructionism

- Structuralism

- Symbolic Interactionism

- Sociology Theorists

- General Sociology

- Social Policy

- Social Work

- Sociology of Childhood

- Sociology of Crime & Deviance

- Sociology of Art

- Sociology of Dance

- Sociology of Food

- Sociology of Sport

- Sociology of Disability

- Sociology of Economics

- Sociology of Education

- Sociology of Emotion

- Sociology of Family & Relationships

- Sociology of Gender

- Sociology of Health

- Sociology of Identity

- Sociology of Ideology

- Sociology of Inequalities

- Sociology of Knowledge

- Sociology of Language

- Sociology of Law

- Sociology of Anime

- Sociology of Film

- Sociology of Gaming

- Sociology of Literature

- Sociology of Music

- Sociology of TV

- Sociology of Migration

- Sociology of Nature & Environment

- Sociology of Politics

- Sociology of Power

- Sociology of Race & Ethnicity

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Sexuality

- Sociology of Social Movements

- Sociology of Technology

- Sociology of the Life Course

- Sociology of Travel & Tourism

- Sociology of Violence & Conflict

- Sociology of Work

- Urban Sociology

- Changing Relationships Within Families

- Conjugal Role Relationships

- Criticisms of Families

- Family Forms

- Functions of the Family

- Featured Articles

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Broken Windows Theory: An Outline and Explanation

Table of Contents

Theoretical foundations, development and popularization.

- Policy Implications

- Case Studies

- Critiques and Counter-Theories

The Broken Windows Theory, first articulated by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling in a 1982 article for The Atlantic , posits that visible signs of disorder and neglect, such as broken windows, can lead to an increase in crime and antisocial behavior. This theory suggests a direct correlation between the maintenance of urban environments and the overall safety and security of those areas. By addressing minor forms of disorder, communities can prevent more serious crimes from occurring. This paper outlines the foundational concepts of the Broken Windows Theory, its development, empirical studies supporting and critiquing it, and its implications for public policy and urban management.

Conceptual Origins

The Broken Windows Theory is rooted in earlier sociological and criminological theories that link environmental conditions to behavioral outcomes. Key influences include:

- The Chicago School of Sociology: This school emphasized the role of social and physical environments in shaping human behavior. The idea of social disorganization, a key concept from the Chicago School, posits that a breakdown in community controls can lead to increased crime and deviance.

- Routine Activities Theory: Developed by Lawrence E. Cohen and Marcus Felson in 1979, this theory argues that crime occurs when a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of a capable guardian converge in time and space. Disorder in public spaces can reduce guardianship and increase opportunities for crime.

Core Premises

The Broken Windows Theory is based on several core premises:

- Disorder Begets Disorder: Visible signs of neglect and disorder, such as graffiti, litter, and broken windows, signal to potential offenders that the area is not monitored or cared for, thereby inviting more serious crimes.

- Normative Influence: Maintaining order in public spaces can reinforce social norms and community standards, which in turn discourages deviant behavior.

- The Role of Policing: The theory advocates for a proactive approach to policing, focusing on maintaining order and addressing minor offenses to prevent more significant crimes.

Initial Publication

Wilson and Kelling’s 1982 article introduced the concept to a broad audience, emphasizing the psychological impact of disorder on community members and potential offenders. They argued that visible neglect fosters an environment where norms of civility are eroded, leading to more serious criminal activity.

Implementation in New York City

The most notable application of Broken Windows Theory occurred in New York City during the 1990s. Under Mayor Rudy Giuliani and Police Commissioner William Bratton, the New York City Police Department (NYPD) implemented policies targeting minor offenses such as vandalism, fare evasion, and public drinking. This approach, known as “zero tolerance” policing, aimed to restore order and reduce crime rates.

Empirical Support and Criticism

Membership required.

You must be a member to access this content.

View Membership Levels

Easy Sociology

Easy Sociology is your go-to resource for clear, accessible, and expert sociological insights. With a foundation built on advanced sociological expertise and a commitment to making complex concepts understandable, Easy Sociology offers high-quality content tailored for students, educators, and enthusiasts. Trusted by readers worldwide, Easy Sociology bridges the gap between academic research and everyday understanding, providing reliable resources for exploring the social world.

Related Articles

Understanding Systemic Corruption in Sociology

Learn about systemic corruption, its causes, manifestations, and consequences. Understand the impact of systemic corruption on society and the need...

Primary and Secondary Deviation

Deviance is a fundamental concept in sociology that refers to actions or behaviors that violate social norms. Understanding the nuances...

How Institutions Limit Free Will and Agency

Us destabilisation of venezuela.

The Washington Consensus

Get the latest sociology.

How would you rate the content on Easy Sociology?

Recommended

Understanding Cultural Pluralism: Embracing Diversity and Inclusion

Understanding and Explaining ‘Lad Culture’ in Sociology

24 hour trending.

Robert Merton’s Strain Theory Explained

The british class system: an outline and explanation, understanding conflict theories in sociology, the connection between education and social stratification, understanding the concept of liquid modernity in sociology.

Easy Sociology makes sociology as easy as possible. Our aim is to make sociology accessible for everybody. © 2023 Easy Sociology

© 2025 Easy Sociology

Your privacy settings

Manage consent preferences, embedded videos, google fonts.

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Sociology news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Sociology Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Study Notes

Broken Windows Theory

Last updated 2 Apr 2018

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

James Q. Wilson concluded that the extent to which a community regulates itself has a dramatic impact on crime and deviance. The "broken windows" referred to in the theory’s name is the idea that where there is one broken window left unreplaced there will be many.

A broken window is a physical symbol that the residents of a particular neighbourhood do not especially care about their environment and that low-level deviance is tolerated. The theory influenced policy-makers on both sides of the Atlantic and, most famously, in New York in the 1990s.

Their response was zero tolerance policing where the criminal justice system took low-level crime and anti-social behaviour much more seriously than they had in the past. This included "three strikes and you're out" policies where people could get serious custodial sentences for repeated minor offences, such as unsolicited windscreen cleaning, prostitution, drunk and disorderly behaviour, etc.

The idea was that low-level crime should not be tolerated and severe penalties needed to be meted out for anti-social behaviour and minor incivilities in order to deter more serious crime and ensure that collective conscience and social solidarity is maintained by clear boundary maintenance.

Evaluating Broken Windows Theory

- The impact of the policy in New York appeared to be dramatic with crime levels (including very serious crimes like murder) falling rapidly. There was a 40% drop in overall crime and over 50% in homicide. Fans of Broken Windows on the political right in America hailed this as a success, but there are two main criticisms.

- This policy coincided with a period of economic growth and a reduction in poverty. Those who feel that social conditions are a stronger driver of crime than broken windows suggest that the crime rates in New York fell because the social conditions for people in New York significantly improved. As such it is possible that it was purely a coincidence that it happened at the same time as the implementation of broken windows. Just because there was a correlation does not mean that there was causality .

- Some accused Broken Windows of achieving control without justice. Yes, the crime rates fell, but people were in prison, sometimes serving long sentences, for very minor misdemeanours. Furthermore, there was evidence showing that the policy impacted much more heavily on minority ethnic groups, particularly African Americans and Latin Americans, than on the majority white population. While poor black people might be arrested for public drunkenness or jay-walking, white middle-class students celebrating the start of their freshman year by doing the same things are tolerated. Therefore, police discretion makes the implementation of broken windows unjust. Supporters of the theory, however, would counter that zero tolerance should mean zero tolerance and white students shouldn't get away with public drunkenness either.

Digital Topic Companions for AQA A Level Sociology

Resource Collection

- Right realism

- Broken Windows Theory

- Crime and Deviance

You might also like

Domestic abuse: precursor to mass violence.

2nd November 2017

19th January 2018

Crime Prevention: Sociological Explanations of Surveillance

Money laundering.

14th May 2019

Video of white woman calling police on black man in Central Park draws outrage

1st June 2020

Gilroy - Theories of Crime and Deviance

Topic Videos

Fines and jail sentences for Covid travel rule breakers

26th February 2021

Crime & Deviance Checklist for AQA A Level Sociology

Exam Support

Our subjects

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

- Everyday Sociology

- Symbolic Interactionism

- Sociology of Crime & Deviance

- Sociology of Disability

- Sociology of Education

- Sociology of Family

- Sociology of Body & Health

- Sociology of Identity

- Sociology of Inequalities

- Sociology of Media

- Sociology of Power

- Sociology of Race & Ethnicity

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Sexuality & Gender

- Sociology of Social Exclusion

- Sociology of Social Movements

- Sociology of Stratification

- Sociology of Technology

- Sociology of Work

- Research Methods

- Guides & How To’s

- Bibliographies

- Conferences & Events

- The Interlocutor

- How to Use This Site

- Write For Us

What is Broken Windows Theory?

Photo by Matt Artz on Unsplash

Broken Windows Theory originated from a 1982 article in Atlantic Monthly written by George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson. The basic idea was that when there is some form of environmental decay, such as broken windows, it gives the impression that the neighbourhood or area is uncared for. In turn, this leads to an increase in crime, especially petty crime such as graffiti or further damage to property. Subsequently, the more decay, the greater the increase and severity of crime and the greater likelihood that social cohesion itself will also break down.

Philip Zimbardo

Kelling & Wilson’s article draws upon a 1969 psychology experiment into human behaviour by Philip Zimbardo (the same Zimbardo who did the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment). Although the psychology element here is of no particular concern in this article, Zimbardo nonetheless had turned his attention to vandalism and the mindless destruction of property along with its associated costs.

Zimbardo ran “ A Field Experiment on “Auto-Shaping” ” to observe vandalism in action. He bought two cars and left one in upmarket Palo Alto in California and one in the Bronx area of New York. As observed:

What happened in New York was unbelievable! Within ten minutes the 1959 Oldsmobile received its first auto strippers—a father, mother, and eight-year-old son. The mother appeared to be a lookout, while the son aided the father’s search of the trunk, glove compartment, and motor. He handed his father the tools necessary to remove the battery and radiator. Total time of destructive contact: seven minutes.

After three days of observation, Zimbardo concluded that the vehicle left in the Bronx had been targeted 23 times leaving the vehicle a complete wreck. Most of the vandalism happened during the day and was perpetrated by “clean-cut whites” who seemingly had the appearance of responsible citizens. On the other hand:

In startling contrast, the Palo Alto car not only emerged untouched, but when it began to rain, one passerby lowered the hood so that the motor would not get wet!

Order vs. Disorder

Kelling & Wilson’s article is very much premised on a dichotomy of order versus disorder. One of the problems here is the idea of what constitutes order and what constitutes disorder especially when Kelling & Wilson argue that “disorder and crime are usually inextricably linked in a kind of developmental sequence”. It seems that they believe order to be what is normal for a specific neighbourhood. This creates a problem where every neighbourhood has a different normal. Further, the use of the term “developmental sequence” seems to suggest small offences inevitably lead to more serious crime. Thus, without addressing minor disorder, more serious problems will inevitably occur. It is a similar argument to that of drug use whereby it is claimed that if a person starts with a soft drug, they will inevitably turn to hard drugs. This could be seen as a slippery slope fallacy.

Zero tolerance

In the 1990’s, New York mayor Rudy Giuliani began a new zero tolerance initiative reportedly on the logic of Broken Windows Theory. Through a heavy crackdown on minor offences such as drunkenness, graffiti, and even jaywalking, the New York police were credited with a 37% drop in crime over three years (Bratton, 1998: 29-43). On the surface, this seems to indicate a success. However, similar reductions in crime rates were also seen across other major U.S. cities around the same time but utilising much different policing methods.

Wacquant (2009b: 265) noted that zero tolerance action was targeted towards those already dispossessed and living in dispossessed districts. Rather than being the restoration of order as theorised by Kelling & Wilson, it was actually a “concentration of police and penal repression” that accounted for the drop in crime. Wacquant also argues that this repression was not linked to any criminological theory and that Broken Windows Theory was actually discovered after the fact and used to mask repressive police activities by presenting them as rational. Essentially, it was a form of punishing the poor.

Other Areas

Broken Windows Theory has also been applied in other areas. Some of these areas are quite unexpected but include tourism (Liu et al., 2019), work environments (Ramos & Torgler, 2012), consumer behaviour (Guido et al., 2015), and education (Kelly, 2017). Shipley & Bowker (2014: 379) also consider Broken Windows Theory as it applies to internet crime.

Internet Policing

The internet is made up of innumerable communities just like the outside world. When online communities are not policed to maintain order, disorder and therefore crime begin to manifest. We could perhaps view this kind of application of Broken Windows Theory to the infamous 4Chan website. Over time, 4Chan grew from a kind of alternative community to being one of the most infamous producers of trouble on the internet. This trouble manifested from low-level trolling to major harassment campaigns as well as other more illegal content. It is important to note that it is individuals in the community who acted in this way but the Broken Windows argument would have it that this is due to lack of policing and orderliness. Individual actions however, bring us to some of the criticisms of Broken Windows Theory.

As Risjord (2014: 130) notes, Broken Windows Theory seems to command a response which demands that areas of decay should be cleaned up and that this itself would then deter crime. However, Risjord argues that “broken windows don’t steal purses”. In other words, investing in the visual quality of an area will make no difference as it is the behaviour of the individual which is the true source of order or disorder. Unless the behaviours and attitudes of those who commit petty crime are turned away from such actions, then nothing is going to change.

Loic Wacquant (2009b: 15) also describes how the conservative-aligned broken windows approach to crime was in fact a “pseudo-criminological alibi for the reorganisation of police work”. Through adopting a punitive approach to crime and masking it behind the veneer of theoretical respectability, it would in turn also be a vote winner amongst the middle and upper classes.

Kelling & Wilson’s original article, like many conservative approaches, widely ignores many other possibilities which could contribute to crime such as:

- Unemployment

- Mental health issues

- Discrimination

This in itself creates a logical issue. These contributors to the causes of crime are ignored which suggests on the one hand that responsibility for crime is therefore located within the individual committing the crime. And yet, on the other hand, it is suggested that some broken windows can encourage crime. Ultimately, the source of crime becomes logically unlocatable. As such, how does one target the sources of crime?

Bratton, W. (1998). Crime is Down in New York City: Blame the Police. In: Zero tolerance: policing a free society . London: Iea Health And Welfare Unit, Cop.

Kelling, G.L. and Wilson, J.Q. (1982). Broken Windows . [online] The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1982/03/broken-windows/304465/.

Kelly, J. M. (2017). The Achievement and Non-Achievement Effects of Repeating Another Year With a Teacher and Reversing Broken Windows Theory . Temple University.

Guido, G., Pino, G., Prete, M. I., & Bruno, I. (2015). Explaining the Deterioration of Elderly Consumers’ Behaviour through the Broken Windows Theory. Journal of Research for Consumers , (28), 1.

Liu, J., Wu, J.S. and Che, T. (2019). Understanding perceived environment quality in affecting tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviours: A broken windows theory perspective. Tourism Management Perspectives , 31, pp.236–244.

Ramos, J. and Torgler, B. (2012). Are Academics Messy? Testing the Broken Windows Theory with a Field Experiment in the Work Environment. Review of Law & Economics , 8(3).

Risjord, M. (2014). Philosophy of Social Science . Routledge.

Shipley, T.G. and Bowker, A. (2014). Investigating internet crimes: an introduction to solving crimes in cyberspace . Waltham, Ma: Syngress.

Wacquant, L. (2009a). Prisons of poverty . Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press.

Wacquant, L. (2009b). Punishing the poor: the neoliberal government of social insecurity . Durham NC: Duke University Press.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1969). The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order versus deindividuation, impulse, and chaos. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 17, 237–307.

Further Reading

Brisman, A., Carrabine, E., & South, N. (2017). The Routledge Companion to Criminological Theory and Concepts . Routledge.

Carrabine, E., Cox, P., Fussey, P., Hobbs, D., South, N., Thiel, D., & Turton, J. (2020). Criminology: A Sociological Introduction . Routledge.

Clinard, M.B. and Meier, R.F. (2015). Sociology of deviant behavior . Boston, Ma, Usa: Cengage Learning.

Downes, D. M., Mclaughlin, E., & Rock, P. E. (2016). Understanding deviance : a guide to the sociology of crime and rule-breaking (7th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gau, J. M., & Pratt, T. C. (2010). Revisiting broken windows theory: Examining the sources of the discriminant validity of perceived disorder and crime. Journal of criminal justice , 38 (4), 758-766.

Harcourt, B. E. (1998). Reflecting on the subject: A critique of the social influence conception of deterrence, the broken windows theory, and order-maintenance policing New York style. Mich. L. Rev. , 97 , 291.

Harcourt, B. E. (2005). Illusion of order: The false promise of broken windows policing . Harvard University Press.

Harcourt, B. E., & Ludwig, J. (2006). Broken windows: New evidence from New York City and a five-city social experiment. U. Chi. L. Rev. , 73 , 271.

Konkel, R. H., Ratkowski, D., & Tapp, S. N. (2019). The effects of physical, social, and housing disorder on neighborhood crime: A contemporary test of broken windows theory. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information , 8 (12), 583.

Newburn, T. (2017). Criminology (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Should I Study Sociology? An Unconventional Guide

Access to he: sociology essay example – social control, dr brian waldock.

Brian has a PhD in sociology. His thesis focused on a range of concepts including platonism, bureaucracy, and abstract space. When not destroying his mind with theories, he indulges in the occasional video game, anime, chinese takeaway, or maybe even a very rare pint.

Related Posts

What are moral panics.

This article looks at the origins of moral panics, the different types of moral panics, and finally some examples which have happened over the course of history

Access to HE: Sociology Essay Example - Social Control

The Zones of Regulation: Institutionalised Emotional Control

The Academic Phrasebank

Help spread sociology.

If you like what I do please support me on Ko-fi

SociologyMag brings you sociology as it occurs within the everyday. SociologyMag also serves you with guides, how-to's, and knowledge to help you succeed within academic sociology at all levels. If you are new here, check out our How to Use This Site page to get the most out of your visit.

Universal Basic Income

Experiences of single-fathers & lone-fathers, attitudes towards single-parents and lone-parents, bibliography: perceptions and attitudes to single-parents & lone-parents, single-mother, bibliography: stepfamilies.

What Are Stepfamilies, Reconstituted Families, and Blended Families?

Stepfamilies, reconstituted families, and blended families are all the same thing. Learn more about these family types...

What is Totemism?

What are Extended Families?

What Are Lone-Parent and Single-Parent Families?

SociologyMag is an educational website designed to bring sociology to a wider audience. We look at how sociology can be used in the everyday by creating content which draws on academic sociology. We also target sociology from the academic side by publishing articles to help students at all levels from beginner to PhD.

Follow us on social media:

© 2022 SociologyMag

- Sociological Perspectives

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Feb 13, 2024 · The Broken Windows Theory of Criminology suggests that visible signs of disorder and neglect, such as broken windows or graffiti, can encourage further crime and anti-social behavior in an area, as they signal a lack of order and law enforcement.

Nov 27, 2018 · In a nutshell, the broken windows thesis (Wilson and Kelling 1982) suggests that police could more effectively fight crime by focusing on more minor annoyances which plague communities – hereafter referred to as disorder (some works also label these issues as “incivilities”). Disorder includes both rundown physical conditions in the form ...

Dec 16, 2024 · They used the image of broken windows to explain how neighbourhoods might decay into disorder and crime if no one attends to their maintenance: a broken factory window suggests to passers-by that no one is in Charge or cares; in time a few more windows are broken by rock-throwing youths; passers-by begin to think that no one cares about the ...

Jun 19, 2024 · The Broken Windows Theory, first articulated by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling in a 1982 article for The Atlantic, posits that visible signs of disorder and neglect, such as broken windows, can lead to an increase in crime and antisocial behavior. This theory suggests a direct correlation between the maintenance of ...

Nov 22, 2024 · Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice - Assessing “Broken Windows”: A Brief Critique; Psychology Today - Broken Windows Theory; Biomed Central - BMC Health Services Research - An empirical application of “broken windows” and related theories in healthcare: examining disorder, patient safety, staff outcomes, and collective efficacy in ...

broken windows in theory and action can prevent more serious crimes from occurring if minor offenses are aggressively policed. Since 1982, broken windows has been inspirational to a number of policing styles and programs in the United States and frequently implemented. With broken windows increasing in popularity, discussion

29 Wilson and Kelling‟s (1982) incivilities/broken windows thesis is graphically represented thus: Figure 3: Broken Windows Theory . Source: Taylor (1996:67) However, the broken windows theory suffers from what Harcourt (2001) referred to as „pervasive lack of empirical evidence‟.

Oct 1, 2013 · The broken windows thesis suggests that disorder is a key part of a cycle of community decline that leaves neighborhoods vulnerable to crime. Some recent research has challenged this thesis by finding limited support for a direct relationship between disorder and crime.

Apr 2, 2018 · The "broken windows" referred to in the theory’s name is the idea that where there is one broken window left unreplaced there will be many. A broken window is a physical symbol that the residents of a particular neighbourhood do not especially care about their environment and that low-level deviance is tolerated. The theory influenced policy ...

Mar 5, 2023 · Broken Windows Theory originated from a 1982 article in Atlantic Monthly written by George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson. The basic idea was that when there is some form of environmental decay, such as broken windows, it gives the impression that the nei