Literature Reviews

- Getting Started

Selecting a topic

Remember the goal of your literature review, planning your research, popular vs. scholarly, finding scholarly journal articles, finding or requesting full-text articles, why not just use google scholar, finding books, open access resources, manage your own downloads and citations, using your own method, managing your citations, organizing your notes: synthesis matrix.

- Literature Review as a Product: Organizing your Writing

- Finding Examples of Literature Reviews

- Resources and Assistance

One of the most important steps in research is selecting a good research topic. This page on the Capstone Research Guide will guide you through selecting a topic, writing a thesis statement and/or research questions, selecting keywords, and recommended databases for preliminary research.

The goal of the literature review is to provide an analysis of the literature and research already published on your subject. You want to read as much as possible on your topic to gain a foundation of the information which already exists and analyze that information to understand how it all relates. This gives you the opportunity to identify possible gaps in the research or justify your own research in relation to what already exists.

This page will walk through the steps in:

- Planning your research

- Collecting your research

- Organizing your notes

After you have chosen your topic, you will want to make a plan for all of the places you should look for information. This will allow you to organize your search and keep track of information as you find it. In a document, make a list of possible places you might find information on your topic. This list might include:

- Library databases - See section "Finding scholarly journal articles" below

- Research facilities - Are there organizations or institutions which publish and share research in your field of study?

- Open Access Journals - See section "Open Access Journals" below

- Webster University library catalog - See section "Finding books" below

- The catalogs of other libraries - See section "Finding books" below

Keep in mind that a literature review necessitates the use of scholarly research. These are peer-reviewed articles written by graduate or post-graduate students, educators, researchers, or professionals in the field. These types of articles wil include standard citations for the works they reference in their research.

What is a scholarly, peer-reviewed journal article?

Scholarly articles are sometimes "peer-reviewed" or "refereed" because they are evaluated by other scholars or experts in the field before being accepted for publication. A scholarly article is commonly an experimental or research study, or an in-depth theoretical or literature review. It is usually many more pages than a magazine article.

The clearest and most reliable indicator of a scholarly article is the presence of references or citations. Look for a list of works cited, a reference list, and/or numbered footnotes or endnotes. Citations are not merely a check against plagiarism. They set the article in the context of a scholarly discussion and provide useful suggestions for further research.

Many of our databases allow you to limit your search to just scholarly articles. This is a useful feature, but it is not 100% accurate in terms of what it includes and what it excludes. You should still check to see if the article has references or citations.

The table below compares some of the differences between magazines (e.g. Psychology Today) and journals (e.g Journal of Abnormal Psychology).

How to find scholarly, peer-reviewed articles

- FAQ: How do I find peer-reviewed or scholarly articles?

- FAQ: How can I tell if an article is peer-reviewed?

To get a sense of the available research, you may want to start with a multidisciplinary article database such as Academic Search Premier or Business Source Complete (for management and business). Then, you may want to do a more thorough search in additional specialized sources--see the link below.

- Academic Search Premier (EBSCO) A scholarly multidisciplinary database of periodical articles, most with full-text, through Ebscohost.

- Business Source Complete (EBSCO) A great starting point for articles on business and management topics including peer-reviewed journals and classic publications such Harvard Business Review. Also contains SWOT, industry, and market research reports.

- Additional specialized sources for finding journal articles Select the areas that correspond to your topic or academic program to find specialized journal article databases.

From a library database

When the PDF or HTML full-text is not available in one of our databases, use the "Full Text Finder" button. Full Text Finder will allow you to link to the article in another database. If no full text is available you may request an electronic copy of the article through Interlibrary Loan .

From another online source

Many articles that you find online may require payment ( aka paywall) to download the article. In many cases the Library can get the article for you for free to keep you from having to pay out of pocket. For more information, please visit:

- Request Articles and Books page For information on how to request items depending on your campus or location

While Google Scholar can be a useful source for finding journal articles, there are advantages found in using Webster University Libraries' databases, including:

- Features that let you customize your search

- Access to more full text materials

- Integration with other library services (e.g., chat, delivery services, etc.).

For more information on using Google Scholar, view the FAQ: How can I connect Google Scholar to the Library?

Do not forget books when you are surveying the literature. They often provide historical information and overviews of current research in a topic area.

- Search for books in the Library Catalog

- Find an ebook on a topic

- MOBIUS Catalog Here you can borrow from a consortium system of college & university libraries in Missouri and other states. (Some public libraries have also joined MOBIUS.)

Here you can search a large catalog of books and other materials owned by U.S libraries and some worldwide locations. This source shows local libraries where a given book is housed and also indicates if there is an ebook available.

When something is published as an open access resource, it is published online and can be accessed for free with few or no copyright restrictions. Open access resources allows you to search, download, and cite researchers who have chosen to publish open access without paying for each article.

Searching through open access resources might be a great option for your research once you have exhausted the databases. Please note that sometimes, an open resource repository can be difficult to search through as often there are fewer ways to limit the search.

- About Open Access guide This research guide provides information about Open Access (OA) and Open Educational Resources (OER) and includes a list of resources by discipline.

As you download articles and begin to identify helpful resources, you will need to develop a method of keeping track of this research. No matter the method you choose to use, make sure that:

- Any article you've downloaded is saved in a labeled folder which is easy to access

- Any citation you have created is saved and accessible

- EBSCO tools If using an EBSCO database, this document provides information on how to create folders and save links to articles within the database.

You can certainly create a system for organizing your downloads, citations, and other electronic notes. Use the file storage system on your computer, or cloud computing software like Google Drive or Dropbox . Create folders specifically for your project and save everything you think you might use. The benefit of managing your research this way is that these options are often free and allow you to have access to materials beyond your time as a Webster student.

There are a number of software programs available that help students store references and notes, create bibliographies, etc. While not needed for every assignment, they are useful for when you are gathering a large number of articles and other resources for projects such as capstone papers, theses, and dissertations. Some of the main citation management software applications are listed here.

Because the purpose of the literature review is to analyze the research on the topic and find relationships between resources, simply reading the resources and keeping notes may not be enough to help you see the connections between the resources.

One option is to create a document with a chart used solely to compare the ideas and methods of various scholars and researchers. This is called a synthesis matrix . Before starting a matrix, you may want to identify a couple subtopics or themes to track within the articles you read. Other themes will reveal themselves as you read the literature and can be added to the chart.

Below, you will find some examples of synthesis matrixes. Use inspiration from any of them to design your own matrix which works best for your style and ideas. No matter the design of your matrix, some of the items you may want to compare across resources are:

Publishing Date : Show how an idea has developed over time due to continuous research.

Research Methods : Discuss findings based upon research type. You might ask yourself: How does the method used to collect the data impact the findings of the study?

- Themes : Which topics are covered in the article and what does the author believe about that topic?

- Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources (Indiana University Bloomington)

- Synthesis Matrix (NC State University)

- Writing a Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix PDF Document created by North Carolina State University and posted by Wayne State University University.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Literature Review as a Product: Organizing your Writing >>

- Last Updated: Oct 12, 2024 4:46 PM

- URL: https://library.webster.edu/litreview

Peer Reviewed Literature

What is peer review, terminology, peer review what does that mean, what types of articles are peer-reviewed, what information is not peer-reviewed, what about google scholar.

- How do I find peer-reviewed articles?

- Scholarly vs. Popular Sources

Research Librarian

For more help on this topic, please contact our Research Help Desk: [email protected] or 781-768-7303. Stay up-to-date on our current hours . Note: all hours are EST.

This Guide was created by Carolyn Swidrak (retired).

Research findings are communicated in many ways. One of the most important ways is through publication in scholarly, peer-reviewed journals.

Research published in scholarly journals is held to a high standard. It must make a credible and significant contribution to the discipline. To ensure a very high level of quality, articles that are submitted to scholarly journals undergo a process called peer-review.

Once an article has been submitted for publication, it is reviewed by other independent, academic experts (at least two) in the same field as the authors. These are the peers. The peers evaluate the research and decide if it is good enough and important enough to publish. Usually there is a back-and-forth exchange between the reviewers and the authors, including requests for revisions, before an article is published.

Peer review is a rigorous process but the intensity varies by journal. Some journals are very prestigious and receive many submissions for publication. They publish only the very best, most highly regarded research.

The terms scholarly, academic, peer-reviewed and refereed are sometimes used interchangeably, although there are slight differences.

Scholarly and academic may refer to peer-reviewed articles, but not all scholarly and academic journals are peer-reviewed (although most are.) For example, the Harvard Business Review is an academic journal but it is editorially reviewed, not peer-reviewed.

Peer-reviewed and refereed are identical terms.

From Peer Review in 3 Minutes [Video], by the North Carolina State University Library, 2014, YouTube (https://youtu.be/rOCQZ7QnoN0).

Peer reviewed articles can include:

- Original research (empirical studies)

- Review articles

- Systematic reviews

- Meta-analyses

There is much excellent, credible information in existence that is NOT peer-reviewed. Peer-review is simply ONE MEASURE of quality.

Much of this information is referred to as "gray literature."

Government Agencies

Government websites such as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) publish high level, trustworthy information. However, most of it is not peer-reviewed. (Some of their publications are peer-reviewed, however. The journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, published by the CDC is one example.)

Conference Proceedings

Papers from conference proceedings are not usually peer-reviewed. They may go on to become published articles in a peer-reviewed journal.

Dissertations

Dissertations are written by doctoral candidates, and while they are academic they are not peer-reviewed.

Many students like Google Scholar because it is easy to use. While the results from Google Scholar are generally academic they are not necessarily peer-reviewed. Typically, you will find:

- Peer reviewed journal articles (although they are not identified as peer-reviewed)

- Unpublished scholarly articles (not peer-reviewed)

- Masters theses, doctoral dissertations and other degree publications (not peer-reviewed)

- Book citations and links to some books (not necessarily peer-reviewed)

- Next: How do I find peer-reviewed articles? >>

- Last Updated: Aug 14, 2024 10:25 AM

- URL: https://libguides.regiscollege.edu/peer_review

Literature Reviews

- Getting Started

- Steps for Conducting a Lit Review

- Finding "The Literature"

- Organizing/Writing

- Peer Review

- Citation/Style Guides This link opens in a new window

Peer Review Video

This video describes and discusses the importance of peer review and its process.

( NCSU video, 3:15 minutes)

This video is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license.

Peer Review - What Does it Mean?

Peer review, also known as refereed, is a process in which experts in related fields of study review and evaluate literature before it is published. It is largely used with research journals to help ensure that published articles represent the best scholarship currently available. When an article is submitted to a peer-reviewed journal, the editors send it to other scholars in the same field (the author's peers) to get their opinion on the quality of the scholarship, its relevance to the field, its appropriateness for the journal, etc.

Publications that don't use peer review (Time, Discover, Newsweek, U.S. News) rely on the judgment of the editors as to whether an article is quality material or not. They are not as reliable because these journals do not rely on solid, scientific scholarship.

Note: This is an entirely different concept from "Review Articles." Those are book reviews.

How Do I Know if a Journal is Peer Reviewed?

Often, you can tell just by looking. A scholarly journal is visibly different from magazines, but occasionally it can be hard to tell. If you want to be certain that a journal is peer-reviewed, limit your searches to Peer Reviewed results. You can also search with Journal Search in OneSearch. Type the journal's title into the text box and search, and your results will provide a variety of information about the journal, including whether the journal contains articles that are peer-reviewed.

Additional Help

You might find that resources provided by your library can be really helpful, and you can access many of these resources online through your library's website. Don't forget that our Librarians are excellent resources!

- << Previous: Organizing/Writing

- Next: Citation/Style Guides >>

- Last Updated: Oct 30, 2024 7:01 PM

- URL: https://westlibrary.txwes.edu/literaturereview

The Sheridan Libraries

- Evaluating Information

- Sheridan Libraries

Types of Articles in Peer Reviewed Publications

- Evaluating Internet Resources

- Evaluating Social Media

- Propaganda, Misinformation, Disinformation

- Peer Review FAQs

Peer-reviewed publications have both peer-reviewed articles and non-peer-reviewed content, including:

- Literature Reviews

- Columns (often opinion pieces)

- Book Reviews ---Brief critical discussion about the merits and weaknesses of a particular book; scholarly books are typically reviewed by other scholars

- Annotated bibliographies ---A list of citations to books, articles, and documents. Each citation is followed by a brief descriptive and evaluative paragraph, which is the annotation. The purpose of the annotations is to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited.

- Literary Reviews ---A brief critical discussion about the merits and weaknesses of a literary work such as a play, novel, or book of poems.

- << Previous: Peer Review

- Next: Peer Review FAQs >>

- Last Updated: Nov 15, 2024 4:47 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/evaluate

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 14 October 2022

- Volume 16 , pages 2577–2595, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sascha Kraus ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4886-7482 1 , 2 ,

- Matthias Breier 3 ,

- Weng Marc Lim 4 , 8 , 22 ,

- Marina Dabić 5 , 6 ,

- Satish Kumar 7 , 8 ,

- Dominik Kanbach 9 , 10 ,

- Debmalya Mukherjee 11 ,

- Vincenzo Corvello 12 ,

- Juan Piñeiro-Chousa 13 ,

- Eric Liguori 14 ,

- Daniel Palacios-Marqués 15 ,

- Francesco Schiavone 16 , 17 ,

- Alberto Ferraris 18 , 21 ,

- Cristina Fernandes 19 , 20 &

- João J. Ferreira 19

101k Accesses

428 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Review articles or literature reviews are a critical part of scientific research. While numerous guides on literature reviews exist, these are often limited to the philosophy of review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures, triggering non-parsimonious reporting and confusion due to overlapping similarities. To address the aforementioned limitations, we adopt a pragmatic approach to demystify and shape the academic practice of conducting literature reviews. We concentrate on the types, focuses, considerations, methods, and contributions of literature reviews as independent, standalone studies. As such, our article serves as an overview that scholars can rely upon to navigate the fundamental elements of literature reviews as standalone and independent studies, without getting entangled in the complexities of review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature Reviews: An Overview of Systematic, Integrated, and Scoping Reviews

On being ‘systematic’ in literature reviews

Debating systematic literature reviews (SLR) and their ramifications for IS: a rejoinder to Mike Chiasson, Briony Oates, Ulrike Schultze, and Richard Watson

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A literature review – or a review article – is “a study that analyzes and synthesizes an existing body of literature by identifying, challenging, and advancing the building blocks of a theory through an examination of a body (or several bodies) of prior work (Post et al. 2020 , p. 352). Literature reviews as standalone pieces of work may allow researchers to enhance their understanding of prior work in their field, enabling them to more easily identify gaps in the body of literature and potential avenues for future research. More importantly, review articles may challenge established assumptions and norms of a given field or topic, recognize critical problems and factual errors, and stimulate future scientific conversations around that topic. Literature reviews Footnote 1 come in many different formats and purposes:

Some review articles conduct a critical evaluation of the literature, whereas others elect to adopt a more exploratory and descriptive approach.

Some reviews examine data, methodologies, and findings, whereas others look at constructs, themes, and theories.

Some reviews provide summaries by holistically synthesizing the existing research on a topic, whereas others adopt an integrative approach by assessing related and interdisciplinary work.

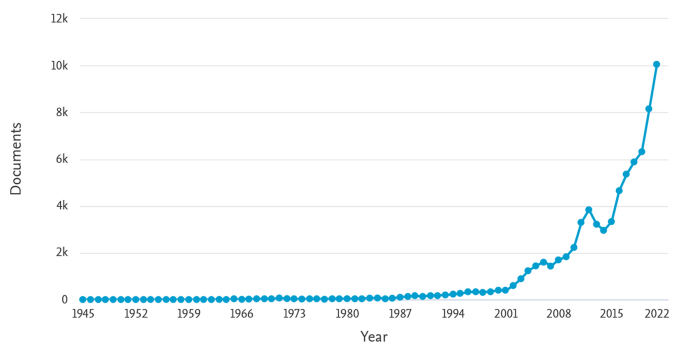

The number of review articles published as independent or standalone studies has been increasing over time. According to Scopus (i.e., search database ), reviews (i.e., document type ) were first published in journals (i.e., source type ) as independent studies in 1945, and they subsequently appeared in three digits yearly from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, four digits yearly from the early 2000s to the late 2010s, and five digits in the year 2021 (Fig. 1 ). This increase is indicative that reviewers and editors in business and management research alike see value and purpose in review articles to such a level that they are now commonly accepted as independent, standalone studies. This development is also reflected in the fact that some academic journals exclusively publish review articles (e.g., the Academy of Management Annals , or the International Journal of Management Reviews ), and journals publishing in various fields often have special issues dedicated to literature reviews on certain topic areas (e.g., the Journal of Management and the Journal of International Business Studies ).

Full-year publication trend of review articles on Scopus (1945–2021)

One of the most important prerequisites of a high-quality review article is that the work follows an established methodology, systematically selects and analyzes articles, and periodically covers the field to identify latest developments (Snyder 2019 ). Additionally, it needs to be reproducible, well-evidenced, and transparent, resulting in a sample inclusive of all relevant and appropriate studies (Gusenbauer and Haddaway 2020; Hansen et al. 2021 ). This observation is in line with Palmatier et al. ( 2018 ), who state that review articles provide an important synthesis of findings and perspectives in a given body of knowledge. Snyder ( 2019 ) also reaffirmed this rationale, pointing out that review articles have the power to answer research questions beyond that which can be achieved in a single study. Ultimately, readers of review articles stand to gain a one-stop, state-of-the-art synthesis (Lim et al. 2022a ; Popli et al. 2022) that encapsulates critical insights through the process of re-interpreting, re-organizing, and re-connecting a body knowledge (Fan et al. 2022 ).

There are many reasons to conduct review articles. Kraus et al. ( 2020 ) explicitly mention the benefits of conducting systematic reviews by declaring that they often represent the first step in the context of larger research projects, such as doctoral dissertations. When carrying out work of this kind, it is important that a holistic overview of the current state of literature is achieved and embedded into a proper synthesis. This allows researchers to pinpoint relevant research gaps and adequately fit future conceptual or empirical studies into the state of the academic discussion (Kraus et al., 2021 ). A review article as an independent or standalone study is a viable option for any academic – especially young scholars, such as doctoral candidates – who wishes to delve into a specific topic for which a (recent) review article is not available.

The process of conducting a review article can be challenging, especially for novice scholars (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic 2015 ). Therefore, it is not surprising that numerous guides have been written in an attempt to improve the quality of review studies and support emerging scholars in their endeavors to have their work published. These guides for conducting review articles span a variety of academic fields, such as engineering education (Borrego et al. 2014 ), health sciences (Cajal et al. 2020 ), psychology (Laher and Hassem 2020 ), supply chain management (Durach et al. 2017 ), or business and entrepreneurship (Kraus et al. 2020 ; Tranfield et al. 2003 ) – the latter were among the first scholars to recognize the need to educate business/management scholars on the roles of review studies in assembling, ascertaining, and assessing the intellectual territory of a specific knowledge domain. Furthermore, they shed light on the stages (i.e., planning the review, conducting the review, reporting, and dissemination) and phases (i.e., identifying the need for a review, preparation of a proposal for a review, development of a review protocol, identification of research, selection of studies, study quality assessment, data extraction and monitoring progress, data synthesis, the report and recommendations, and getting evidence into practice) of conducting a systematic review. Other scholars have either adapted and/or developed new procedures (Kraus et al. 2020 ; Snyder 2019 ) or established review protocols such as the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Moher et al. 2015 ). The latter provides a checklist that improves transparency and reproducibility, thus reducing questionable research practices. The declarative and procedural knowledge of a checklist allows users to derive value from (and, in some cases, produce) methodological literature reviews.

Two distinct and critical gaps or issues provide impetus for our article. First, while the endeavors of the named scholars are undoubtedly valuable contributions, they often encourage other scholars to explain the methodology of their review studies in a non-parsimonious way ( 1st issue ). This can become problematic if this information distracts and deprives scholars from providing richer review findings, particularly in instances in which publication outlets impose a strict page and/or word limit. More often than not, the early parts (i.e., stages/phases, such as needs, aims, and scope) of these procedures or protocols are explained in the introduction, but they tend to be reiterated in the methodology section due to the prescription of these procedures or protocols. Other parts of these procedures or protocols could also be reported more parsimoniously, for example, by filtering out documents, given that scientific databases (such as Scopus or Web of Science ) have since been upgraded to allow scholars to select and implement filtering criteria when conducting a search (i.e., criterion-by-criterion filtering may no longer be necessary). More often than not, the procedures or protocols of review studies can be signposted (e.g., bracket labeling) and disclosed in a sharp and succinct manner while maintaining transparency and replicability.

Other guides have been written to introduce review nomenclatures (i.e., names/naming) and their equivalent philosophical underpinnings. Palmatier et al. ( 2018 ) introduced three clearly but broadly defined nomenclatures of literature reviews as independent studies: domain-based reviews, theory-based reviews, and method-based reviews. However, such review nomenclatures can be confusing due to their overlapping similarities ( 2nd issue ). For example, Lim et al. ( 2022a ) highlighted their observation that the review nomenclatures associated with domain-based reviews could also be used for theory-based and method-based reviews.

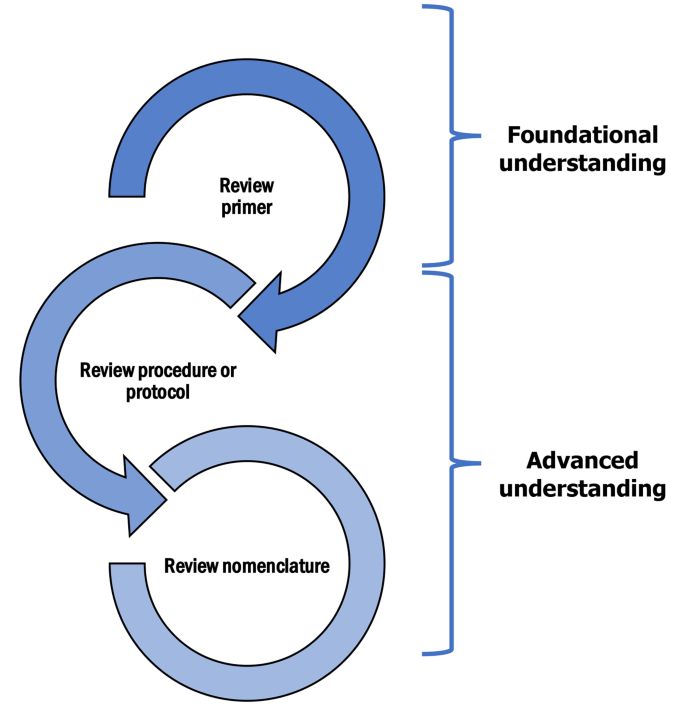

The two aforementioned issues – i.e., the lack of a parsimonious understanding and the reporting of the review methodology , and the confusion emerging from review nomenclatures – are inarguably the unintended outcomes of diving into an advanced (i.e., higher level) understanding of literature review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures from a philosophical perspective (i.e., underpinnings) without a foundational (i.e., basic level) understanding of the fundamental (i.e., core) elements of literature reviews from a pragmatic perspective. Our article aims to shed light on these issues and hopes to provide clarity for future scholarly endeavors.

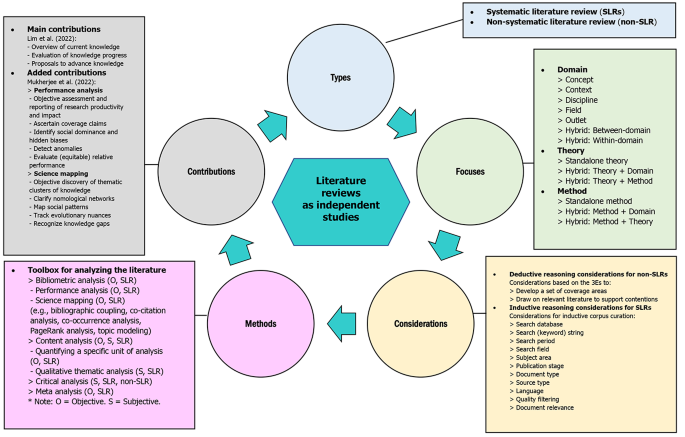

Having a foundational understanding of literature reviews as independent studies is (i) necessary when addressing the aforementioned issues; (ii) important in reconciling and scaffolding our understanding, and (iii) relevant and timely due to the proliferation of literature reviews as independent studies. To contribute a solution toward addressing this gap , we aim to demystify review articles as independent studies from a pragmatic standpoint (i.e., practicality). To do so, we deliberately (i) move away from review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures, and (ii) invest our attention in developing a parsimonious, scaffolded understanding of the fundamental elements (i.e., types, focuses, considerations, methods, and contributions) of review articles as independent studies.

Three contributions distinguish our article. It is worth noting that pragmatic guides (i.e., foundational knowledge), such as the present one, are not at odds with extant philosophical guides (i.e., advanced knowledge), but rather they complement them. Having a foundational knowledge of the fundamental elements of literature reviews as independent studies is valuable , as it can help scholars to (i) gain a good grasp of the fundamental elements of literature reviews as independent studies ( 1st contribution ), and (ii) mindfully adopt or adapt existing review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures to better suit the circumstances of their reviews (e.g., choosing and developing a well-defined review nomenclature, and choosing and reporting on review considerations and steps more parsimoniously) ( 2nd contribution ). Therefore, this pragmatic guide serves as (iii) a foundational article (i.e., preparatory understanding) for literature reviews as independent studies ( 3rd contribution ). Following this, extant guides using a philosophical approach (i.e., advanced understanding) could be relied upon to make informed review decisions (e.g., adoption, adaptation) in response to the conventions of extant review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures (Fig. 2 ).

Foundational and advanced understanding of literature reviews as independent studies

2 Fundamental elements of literature reviews as independent studies

A foundational understanding of literature reviews as independent studies can be acquired through the appreciation of five fundamental elements – i.e., types, focuses, considerations, methods, and contributions – which are illustrated in Fig. 3 and summarized in the following sections.

Fundamental elements of literature reviews as independent studies

There are two types of literature reviews as independent studies: systematic literature reviews ( SLRs ) and non-systematic literature reviews ( non-SLRs ). It is important to recognize that SLRs and non-SLRs are not review nomenclatures (i.e., names/naming) but rather review types (i.e., classifications).

In particular, SLRs are reviews carried out in a systematic way using an adopted or adapted procedure or protocol to guide data curation and analysis, thus enabling transparent disclosure and replicability (Lim et al. 2022a ; Kraus et al. 2020 ). Therefore, any review nomenclature guided by a systematic methodology is essentially an SLR. The origin of this type of literature review can be traced back to the evidence-based medicine movement in the early 1990s, with the objective being to overcome the issue of inconclusive findings in studies for medical treatments (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic 2015 ).

In contrast, non-SLRs are reviews conducted without any systematic procedure or protocol; instead, they weave together relevant literature based on the critical evaluations and (subjective) choices of the author(s) through a process of discovery and critique (e.g., pointing out contradictions and questioning assertions or beliefs); they are shaped by the exposure, expertise, and experience (i.e., the “3Es” in judgement calls) of the author(s). Therefore, non-SLRs are essentially critical reviews of the literature (Lim and Weissmann 2021 ).

2.2 Focuses

Unlike Palmatier et al. ( 2018 ) who considered domain-based reviews, theory-based reviews, and method-based reviews as review nomenclatures, we consider domain , theory , and method as three substantive focuses that can take center stage in literature reviews as independent studies. This is in line with our attempt to move away from review nomenclatures when providing a foundational understanding of literature reviews as independent studies.

A review that is domain-focused can examine: (i) a concept (e.g., customer engagement; Lim et al. 2022b ; digital transformation; Kraus et al. 2021 ; home sharing; Lim et al. 2021 ; sharing economy; Lim 2020 ), (ii) a context (e.g., India; Mukherjee et al. 2022a ), (iii) a discipline (e.g., entrepreneurship; Ferreira et al. 2015 ; international business; Ghauri et al. 2021 ), (iv) a field (e.g., family business; Lahiri et al. 2020 ; Rovelli et al. 2021 ; female entrepreneurship; Ojong et al. 2021 ), or (v) an outlet (e.g., Journal of Business Research ; Donthu et al. 2020 ; Management International Review ; Mukherjee et al. 2021 ; Review of Managerial Science ; Mas-Tur et al. 2020 ), which typically offer broad, overarching insights.

Domain-focused hybrids , such as the between-domain hybrid (e.g., concept-discipline hybrid, such as digital transformation in business and management; Kraus et al. 2022 ; religion in business and entrepreneurship; Kumar et al. 2022a ; personality traits in entrepreneurship; Salmony and Kanbach 2022 ; and policy implications in HR and OB research; Aguinis et al., 2022 ) and the within-domain hybrid (e.g., the concept-concept hybrid, such as customer engagement and social media; Lim and Rasul 2022 ; and global business and organizational excellence; Lim 2022 ; and the discipline-discipline hybrid, such as neuromarketing; Lim 2018 ) are also common as they can provide finer-grained insights.

A review that is theory-focused can explore a standalone theory (e.g., theory of planned behavior; Duan and Jiang 2008 ), as well as a theory in conjunction with a domain , such as the concept-theory hybrid (e.g., behavioral control and theory of planned behavior; Lim and Weissmann 2021 ) and the theory-discipline hybrid (e.g., theory of planned behavior in hospitality, leisure, and tourism; Ulker-Demirel and Ciftci 2020 ), or a theory in conjunction with a method (e.g., theory of planned behavior and structural equation modeling).

A review that is method-focused can investigate a standalone method (e.g., structural equation modeling; Deng et al. 2018 ) or a method in conjunction with a domain , such as the method-discipline hybrid (e.g., fsQCA in business and management; Kumar et al. 2022b ).

2.3 Planning the review, critical considerations, and data collection

The considerations required for literature reviews as independent studies depend on their type: SLRs or non-SLRs.

For non-SLRs, scholars often rely on the 3Es (i.e., exposure, expertise, and experience) to provide a critical review of the literature. Scholars who embark on non-SLRs should be well versed with the literature they are dealing with. They should know the state of the literature (e.g., debatable, underexplored, and well-established knowledge areas) and how it needs to be deciphered (e.g., tenets and issues) and approached (e.g., reconciliation proposals and new pathways) to advance theory and practice. In this regard, non-SLRs follow a deductive reasoning approach, whereby scholars initially develop a set of coverage areas for reviewing a domain, theory, or method and subsequently draw on relevant literature to shed light and support scholarly contentions in each area.

For SLRs, scholars often rely on a set of criteria to provide a well-scoped (i.e., breadth and depth), structured (i.e., organized aspects), integrated (i.e., synthesized evidence) and interpreted/narrated (i.e., describing what has happened, how and why) systematic review of the literature. Footnote 2 In this regard, SLRs follow an inductive reasoning approach, whereby a set of criteria is established and implemented to develop a corpus of scholarly documents that scholars can review. They can then deliver a state-of-the-art overview, as well as a future agenda for a domain, theory, or method. Such criteria are often listed in philosophical guides on SLR procedures (e.g., Kraus et al. 2020 ; Snyder 2019 ) and protocols (e.g., PRISMA), and they may be adopted/adapted with justifications Footnote 3 . Based on their commonalities they can be summarized as follows:

Search database (e.g., “Scopus” and/or “Web of Science”) can be defined based on justified evidence (e.g., by the two being the largest scientific databases of scholarly articles that can provide on-demand bibliographic data or records; Pranckutė 2021 ). To avoid biased outcomes due to the scope covered by the selected database, researchers could utilize two or more different databases (Dabić et al. 2021 ).

Search keywords may be developed by reading scholarly documents and subsequently brainstorming with experts. The expanding number of databases, journals, periodicals, automated approaches, and semi-automated procedures that use text mining and machine learning can offer researchers the ability to source new, relevant research and forecast the citations of influential studies. This enables them to determine further relevant articles.

Boolean operators (e.g., AND, OR) should be strategically used in developing the string of search keywords (e.g., “engagement” AND “customer” OR “consumer” OR “business”). Furthermore, the correct and precise application of quotation marks is important but is very frequently sidestepped, resulting in incorrect selection processes and differentiated results.

Search period (e.g., between a specified period [e.g., 2000 to 2020] or up to the latest full year at the time or writing [e.g., up to 2021]) can be defined based on the justified scope of study (e.g., contemporary evolution versus historical trajectory).

Search field (e.g., “article title, abstract, keywords”) can be defined based on justified assumptions (e.g., it is assumed that the focus of relevant documents will be mentioned in the article title, abstract, and/or keywords).

Subject area (e.g., “business, management, and accounting”) can be defined based on justified principles (e.g., the focus of the review is on the marketing discipline, which is located under the “business, management, and accounting” subject area in Scopus).

Publication stage (e.g., “final”) can be defined based on justified grounds (e.g., enabling greater accuracy in replication).

Document type (e.g., “article” and/or “review”), which reflects the type of scientific/practical contributions (e.g., empirical, synthesis, thought), can be defined based on justified rationales (e.g., articles selected because they are peer-reviewed; editorials not selected because they are not peer-reviewed).

Source type (e.g., “journal”) can be defined based on justified reasons (e.g., journals selected because they publish finalized work; conference proceedings not selected because they are work in progress, and in business/management, they are usually not being considered as full-fledged “publications”).

Language (e.g., “English”) can be determined based on justified limitations (e.g., nowadays, there are not many reasons to use another language besides the academic lingua franca English). Different spellings should also be considered, as the literature may contain both American and British spelling variants (e.g., organization and organisation). Truncation and wildcards in searches are recommended to capture both sets of spellings. It is important to note that each database varies in its symbology.

Quality filtering (e.g., “A*” and “A” or “4*”, “4”, and “3”) can be defined based on justified motivations (e.g., the goal is to unpack the most originally and rigorously produced knowledge, which is the hallmark of premier journals, such as those ranked “A*” and “A” by the Australian Business Deans Council [ABDC] Journal Quality List [JQL] and rated “4*”, “4”, and “3” by the Chartered Association of Business Schools [CABS] Academic Journal Guide [AJG]).

Document relevance (i.e., within the focus of the review) can be defined based on justified judgement (e.g., for a review focusing on customer engagement, articles that mention customer engagement as a passing remark without actually investigating it would be excluded).

Others: Screening process should be accomplished by beginning with the deduction of duplicate results from other databases, tracked using abstract screening to exclude unfitting studies, and ending with the full-text screening of the remaining documents.

Others: Exclusion-inclusion criteria interpretation of the abstracts/articles is obligatory when deciding whether or not the articles dealt with the matter. This step could involve removing a huge percentage of initially recognized articles.

Others: Codebook building pertains to the development of a codebook of the main descriptors within a specific field. An inductive approach can be followed and, in this case, descriptors are not established beforehand. Instead, they are established through the analysis of the articles’ content. This procedure is made up of several stages: (i) the extraction of important content from titles, abstracts, and keywords; (ii) the classification of this content to form a reduced list of the core descriptors; and (iii) revising the codebook in iterations and combining similar categories, thus developing a short list of descriptors (López-Duarte et al. 2016 , p. 512; Dabić et al. 2015 ; Vlacic et al. 2021 ).

2.4 Methods

Various methods are used to analyze the pertinent literature. Often, scholars choose a method for corpus analysis before corpus curation. Knowing the analytical technique beforehand is useful, as it allows researchers to acquire and prepare the right data in the right format. This typically occurs when scholars have decided upon and justified pursuing a specific review nomenclature upfront (e.g., bibliometric reviews) based on the problem at hand (e.g., broad domain [outlet] with a large corpus [thousands of articles], such as a premier journal that has been publishing for decades) (Donthu et al. 2021 ). However, this may not be applicable in instances where (i) scholars do not curate a corpus of articles (non-SLRs), and (ii) scholars only know the size of the corpus of articles once that corpus is curated (SLRs). Therefore, scholars may wish to decide on a method of analyzing the literature depending on (i) whether they rely on a corpus of articles (i.e., yes or no), and (ii) the size of the corpus of articles that they rely on to review the literature (i.e., n = 0 to ∞).

When analytical techniques (e.g., bibliometric analysis, critical analysis, meta-analysis) are decoupled from review nomenclatures (e.g., bibliometric reviews, critical reviews, meta-analytical reviews), we uncover a toolbox of the following methods for use when analyzing the literature:

Bibliometric analysis measures the literature and processes data by using algorithm, arithmetic, and statistics to analyze, explore, organize, and investigate large amounts of data. This enables scholars to identify and recognize potential “hidden patterns” that could help them during the literature review process. Bibliometrics allows scholars to objectively analyze a large corpus of articles (e.g., high hundreds or more) using quantitative techniques (Donthu et al. 2021 ). There are two overarching categories for bibliometric analysis: performance analysis and science mapping. Performance analysis enables scholars to assess the productivity (publication) and impact (citation) of the literature relating to a domain, method, or theory using various quantitative metrics (e.g., average citations per publication or year, h -index, g -index, i -index). Science mapping grants scholars the ability to map the literature in that domain, method, or theory based on bibliographic data (e.g., bibliographic coupling generates thematic clusters based on similarities in shared bibliographic data [e.g., references] among citing articles; co-citation analysis generates thematic clusters based on commonly cited articles; co-occurrence analysis generates thematic clusters based on bibliographic data [e.g., keywords] that commonly appear together; PageRank analysis generates thematic clusters based on articles that are commonly cited in highly cited articles; and topic modeling generates thematic clusters based on the natural language processing of bibliographic data [e.g., article title, abstract, and keywords]). Footnote 4 Given the advancement in algorithms and technology, reviews using bibliometric analysis are considered to be smart (Kraus et al. 2021 ) and technologically-empowered (Kumar et al. 2022b ) SLRs, in which a review has harnessed the benefits of (i) the machine learning of the bibliographic data of scholarly research from technologically-empowered scientific databases, and (ii) big data analytics involving various science mapping techniques (Kumar et al. 2022c ).

Content analysis allows scholars to analyze a small to medium corpus of articles (i.e., tens to low hundreds) using quantitative and qualitative techniques. From a quantitative perspective , scholars can objectively carry out a content analysis by quantifying a specific unit of analysis . A useful method of doing so involves adopting, adapting, or developing an organizing framework . For example, Lim et al. ( 2021 ) employed an organizing (ADO-TCM) framework to quantify content in academic literature based on: (i) the categories of knowledge; (ii) the relationships between antecedents, decisions, and outcomes; and (iii) the theories, contexts, and methods used to develop the understanding for (i) and (ii). The rapid evolution of software for content analysis allows scholars to carry out complex elaborations on the corpus of analyzed articles, so much so that the most recent software enables the semi-automatic development of an organizing framework (Ammirato et al. 2022 ). From a qualitative perspective , scholars can conduct a content analysis or, more specifically, a thematic analysis , by subjectively organizing the content into themes. For example, Creevey et al. ( 2022 ) reviewed the literature on social media and luxury, providing insights on five core themes (i.e., luxury brand strategy, luxury brand social media communications, luxury consumer attitudes and perceptions, engagement, and the influence of social media on brand performance-related outcomes) generated through a content (thematic) analysis. Systematic approaches for inductive concept development through qualitative research are similarly applied in literature reviews in an attempt to reduce the subjectivity of derived themes. Following the principles of the approach by Gioia et al. ( 2012 ), Korherr and Kanbach ( 2021 ) develop a taxonomy of human-related capabilities in big data analytics. Building on a sample of 75 studies for the literature review, 33 first-order concepts are identified. These are categorized into 15 second-order themes and are finally merged into five aggregate dimensions. Using the same procedure, Leemann and Kanbach ( 2022 ) identify 240 idiosyncratic dynamic capabilities in a sample of 34 studies for their literature review. They then categorize these into 19 dynamic sub-capabilities. The advancement of technology also makes it possible to conduct content analysis using computer assisted qualitative data analysis (CAQDA) software (e.g., ATLAS.ti, Nvivo, Quirkos) (Lim et al. 2022a ).

Critical analysis allows scholars to subjectively use their 3Es (i.e., exposure, expertise, and experience) to provide a critical evaluation of academic literature. This analysis is typically used in non-SLRs, and can be deployed in tandem with other analyses, such as bibliometric analysis and content analysis in SLRs, which are used to discuss consensual, contradictory, and underexplored areas of the literature. For SLRs, scholars are encouraged to engage in critical evaluations of the literature so that they can truly contribute to advancing theory and practice (Baker et al. 2022 ; Lim et al. 2022a ; Mukherjee et al. 2022b ).

Meta-analysis allows scholars to objectively establish a quantitative estimate of commonly studied relationships in the literature (Grewal et al. 2018 ). This analysis is typically employed in SLRs intending to reconcile a myriad of relationships (Lim et al. 2022a ). The relationships established are often made up of conflicting evidence (e.g., a positive or significant effect in one study, but a negative or non-significant effect in another study). However, through meta-analysis, scholars are able to identify potential factors (e.g., contexts or sociodemographic information) that may have led to the conflict.

Others: Multiple correspondence analysis helps to map the field, assessing the associations between qualitative content within a matrix of variables and cases. Homogeneity Analysis by Means of Alternating Least Squares ( HOMALS ) is also considered useful in allowing researchers to map out the intellectual structure of a variety of research fields (Gonzalez-Loureiro et al. 2015 ; Gonzalez-Louriero 2021; Obradović et al. 2021 ). HOMALS can be performed in R or used along with a matrix through SPSS software. In summary, the overall objective of this analysis is to discover a low dimensional representation of the original high dimensional space (i.e., the matrix of descriptors and articles). To measure the goodness of fit, a loss function is used. This function is used minimally, and the HOMALS algorithm is applied to the least squares loss functions in SPSS. This analysis provides a proximity map, in which articles and descriptors are shown in low-dimensional spaces (typically on two axes). Keywords are paired and each couple that appears together in a large number of articles is shown to be closer on the map and vice-versa.

When conducting a literature review, software solutions allow researchers to cover a broad range of variables, from built-in functions of statistical software packages to software orientated towards meta-analyses, and from commercial to open-source solutions. Personal preference plays a huge role, but the decision as to which software will be the most useful is entirely dependent on how complex the methods and the dataset are. Of all the commercial software providers, we have found the built-in functions of (i) R and VOSviewer most useful in performing bibliometric analysis (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017 ; R Core Team 2021 ; Van Eck and Waltman 2014 ) and (ii) Stata most useful in performing meta-analytical tasks.

Many different analytical tools have been used. These include simple document counting, citation analysis, word frequency analysis, cluster analysis, co-word analysis, and cooperation analysis (Daim et al. 2006 ). Software has also been produced for bibliometric analysis, such as the Thomson Data Analyzer (TDA), which Thomson Reuters created, and CiteSpace developed by Chen ( 2013 ). VOSviewer helps us to construct and visualize bibliometric networks, which can include articles, journals, authors, countries, and institutions, among others (Van Eck and Waltman 2014 ). These can be organized based on citations, co-citations, bibliographic coupling, or co-authorship relations. In addition, VOSviewer provides text mining functions, which can be used to facilitate a better understanding of co-occurrence networks with regards to the key terms taken from a body of scientific literature (Donthu et al. 2021 ; Wong 2018 ). Other frequently used tools include for bibliometric analysis include Bibliometrix/Biblioshiny in R, CitNetExplorer, and Gephi, among others.

2.5 Contributions

Well-conducted literature reviews may make multiple contributions to the literature as standalone, independent studies.

Generally, there are three primary contributions of literature reviews as independent studies: (i) to provide an overview of current knowledge in the domain, method, or theory, (ii) to provide an evaluation of knowledge progression in the domain, method, or theory, including the establishment of key knowledge, conflicting or inconclusive findings, and emerging and underexplored areas, and (iii) to provide a proposal for potential pathways for advancing knowledge in the domain, method, or theory (Lim et al. 2022a , p. 487). Developing theory through literature reviews can take many forms, including organizing and categorizing the literature, problematizing the literature, identifying and exposing contradictions, developing analogies and metaphors, and setting out new narratives and conceptualizations (Breslin and Gatrell 2020 ). Taken collectively, these contributions offer crystalized, evidence-based insights that both ‘mine’ and ‘prospect’ the literature, highlighting extant gaps and how they can be resolved (e.g., flags paradoxes or theoretical tensions, explaining why something has not been done, what the challenges are, and how these challenges can be overcome). These contributions can be derived through successful bibliometric analysis, content analysis, critical analysis, and meta-analysis.

Additionally, the deployment of specific methods can bring in further added value. For example, a performance analysis in a bibliometric analysis can contribute to: (i) objectively assessing and reporting research productivity and impact ; (ii) ascertaining reach for coverage claims ; (iii) identifying social dominance and hidden biases ; (iv) detecting anomalies ; and (v) evaluating ( equitable ) relative performance ; whereas science mapping in bibliometric analysis can contribute to: (i) objectively discovering thematic clusters of knowledge ; (ii) clarifying nomological networks ; (iii) mapping social patterns ; (iv) tracking evolutionary nuances ; and (v) recognizing knowledge gaps (Mukherjee et al. 2022b , p. 105).

3 Conclusion

Independent literature reviews will continue to be written as a result of their necessity, importance, relevance, and urgency when it comes to advancing knowledge (Lim et al. 2022a ; Mukherjee et al. 2022b ), and this can be seen in the increasing number of reviews being published over the last several years. Literature reviews advance academic discussion. Journal publications on various topics and subject areas are becoming more frequent sites for publication. This trend will only heighten the need for literature reviews. This article offers directions and control points that address the needs of three different stakeholder groups: producers (i.e., potential authors), evaluators (i.e., journal editors and reviewers), and users (i.e., new researchers looking to learn more about a particular methodological issue, and those teaching the next generation of scholars). Future producers will derive value from this article’s teachings on the different fundamental elements and methodological nuances of literature reviews. Procedural knowledge (i.e., using control points to assist in decision-making during the manuscript preparation phase) will also be of use. Evaluators will be able to make use of the procedural and declarative knowledge evident in control points as well. As previously outlined, the need to cultivate novelty within research on business and management practices is vital. Scholars must also be supported to choose not only safe mining approaches; they should also be encouraged to attempt more challenging and risky ventures. It is important to note that abstracts often seem to offer a lot of potential, stating that authors intend to make large conceptual contributions, broadening the horizons of the field.

Our article offers important insights also for practitioners. Noteworthily, our framework can support corporate managers in decomposing and better understanding literature reviews as ad-hoc and independent studies about specific topics that matter for their organization. For instance, practitioners can understand more easily what are the emerging trends within their domain of interest and make corporate decisions in line with such trends.

This article arises from an intentional decoupling from philosophy, in favor of adopting a more pragmatic approach. This approach can assist us in clarifying the fundamental elements of literature reviews as independent studies. Five fundamental elements must be considered: types, focuses, considerations, methods, and contributions. These elements offer a useful frame for scholars starting to work on a literature review. Overview articles (guides) such as ours are thus invaluable, as they equip scholars with a solid foundational understanding of the integral elements of a literature review. Scholars can then put these teachings into practice, armed with a better understanding of the philosophy that underpins the procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures of literature reviews as independent studies.

Data availability

Our manuscript has no associate data.

Our focus here is on standalone literature reviews in contrast with literature reviews that form the theoretical foundation for a research article.

Scoping reviews, structured reviews, integrative reviews, and interpretive/narrative reviews are commonly found in review nomenclature. However, the philosophy of these review nomenclatures essentially reflects what constitutes a good SLR. That is to say, a good SLR should be well scoped, structured, integrated, and interpreted/narrated. This observation reaffirms our position and the value of moving away from review nomenclatures to gain a foundational understanding of literature reviews as independent studies.

Given that many of these considerations can be implemented simultaneously in contemporary versions of scientific databases, scholars may choose to consolidate them into a single (or a few) step(s), where appropriate, so that they can be reported more parsimoniously. For a parsimonious but transparent and replicable exemplar, see Lim ( 2022 ).

Where keywords are present (e.g., author keywords or keywords derived from machine learning [e.g., natural language processing]), it is assumed that each keyword represents a specific meaning (e.g., topic [concept, context], method), and that a collection of keywords grouped under the same cluster represents a specific theme.

Aguinis H, Jensen SH, Kraus S (2022) Policy implications of organizational behavior and human resource management research. Acad Manage Perspect 36(3):1–22

Article Google Scholar

Ammirato S, Felicetti AM, Rogano D, Linzalone R, Corvello V (2022) Digitalising the systematic literature review process: The My SLR platform. Knowl Manage Res Pract. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2022.2041375

Aria M, Cuccurullo C (2017) bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J Informetrics 11(4):959–975

Baker WE, Mukherjee D, Perin MG (2022) Learning orientation and competitive advantage: A critical synthesis and future directions. J Bus Res 144:863–873

Boell SK, Cecez-Kecmanovic D (2015) On being ‘systematic’ in literature reviews. J Inform Technol 30:161–173

Borrego M, Foster MJ, Froyd JE (2014) Systematic literature reviews in engineering education and other developing interdisciplinary fields. J Eng Educ 103(1):45–76

Breslin D, Gatrell C (2020) Theorizing through literature reviews: The miner-prospector continuum. Organizational Res Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120943288 (in press)

Cajal B, Jiménez R, Gervilla E, Montaño JJ (2020) Doing a systematic review in health sciences. Clínica y Salud 31(2):77–83

Chen C (2013) Mapping scientific frontiers: The quest for knowledge visualization. Springer Science & Business Media

Creevey D, Coughlan J, O’Connor C (2022) Social media and luxury: A systematic literature review. Int J Manage Reviews 24(1):99–129

Dabić M, González-Loureiro M, Harvey M (2015) Evolving research on expatriates: what is ‘known’after four decades (1970–2012). Int J Hum Resource Manage 26(3):316–337

Dabić M, Vlačić B, Kiessling T, Caputo A, Pellegrini M(2021) Serial entrepreneurs: A review of literature and guidance for future research.Journal of Small Business Management,1–36

Daim TU, Rueda G, Martin H, Gerdsri P (2006) Forecasting emerging technologies: Use of bibliometrics and patent analysis. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 73(8):981–1012

Deng L, Yang M, Marcoulides KM (2018) Structural equation modeling with many variables: A systematic review of issues and developments. Front Psychol 9:580

Donthu N, Kumar S, Pattnaik D (2020) Forty-five years of Journal of Business Research: A bibliometric analysis. J Bus Res 109:1–14

Donthu N, Kumar S, Mukherjee D, Pandey N, Lim WM (2021) How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J Bus Res 133:285–296

Duan W, Jiang G (2008) A review of the theory of planned behavior. Adv Psychol Sci 16(2):315–320

Google Scholar

Durach CF, Kembro J, Wieland A (2017) A new paradigm for systematic literature reviews in supply chain management. J Supply Chain Manage 53(4):67–85

Fan D, Breslin D, Callahan JL, Szatt-White M (2022) Advancing literature review methodology through rigour, generativity, scope and transparency. Int J Manage Reviews 24(2):171–180

Ferreira MP, Reis NR, Miranda R (2015) Thirty years of entrepreneurship research published in top journals: Analysis of citations, co-citations and themes. J Global Entrepreneurship Res 5(1):1–22

Ghauri P, Strange R, Cooke FL (2021) Research on international business: The new realities. Int Bus Rev 30(2):101794

Gioia DA, Corley KG, Hamilton AL (2012) Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the gioia methodology. Organizational Res Methods 16(1):15–31

Gonzalez-Loureiro M, Dabić M, Kiessling T (2015) Supply chain management as the key to a firm’s strategy in the global marketplace: Trends and research agenda. Int J Phys Distribution Logistics Manage 45(1/2):159–181. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-05-2013-0124

Grewal D, Puccinelli N, Monroe KB (2018) Meta-analysis: Integrating accumulated knowledge. J Acad Mark Sci 46(1):9–30

Hansen C, Steinmetz H, Block J(2021) How to conduct a meta-analysis in eight steps: a practical guide.Management Review Quarterly,1–19

Korherr P, Kanbach DK (2021) Human-related capabilities in big data analytics: A taxonomy of human factors with impact on firm performance. RMS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00506-4 (in press)

Kraus S, Breier M, Dasí-Rodríguez S (2020) The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int Entrepreneurship Manage J 16(3):1023–1042

Kraus S, Durst S, Ferreira J, Veiga P, Kailer N, Weinmann A (2022) Digital transformation in business and management research: An overview of the current status quo. Int J Inf Manag 63:102466

Kraus S, Jones P, Kailer N, Weinmann A, Chaparro-Banegas N, Roig-Tierno N (2021) Digital transformation: An overview of the current state of the art of research. Sage Open 11(3):1–15

Kraus S, Mahto RV, Walsh ST (2021) The importance of literature reviews in small business and entrepreneurship research. J Small Bus Manage. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1955128 (in press)

Kumar S, Sahoo S, Lim WM, Dana LP (2022a) Religion as a social shaping force in entrepreneurship and business: Insights from a technology-empowered systematic literature review. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 175:121393

Kumar S, Sahoo S, Lim WM, Kraus S, Bamel U (2022b) Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) in business and management research: A contemporary overview. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 178:121599

Kumar S, Sharma D, Rao S, Lim WM, Mangla SK (2022c) Past, present, and future of sustainable finance: Insights from big data analytics through machine learning of scholarly research. Ann Oper Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-04410-8 (in press)

Laher S, Hassem T (2020) Doing systematic reviews in psychology. South Afr J Psychol 50(4):450–468

Leemann N, Kanbach DK (2022) Toward a taxonomy of dynamic capabilities – a systematic literature review. Manage Res Rev 45(4):486–501

Lahiri S, Mukherjee D, Peng MW (2020) Behind the internationalization of family SMEs: A strategy tripod synthesis. Glob Strategy J 10(4):813–838

Lim WM (2018) Demystifying neuromarketing. J Bus Res 91:205–220

Lim WM (2020) The sharing economy: A marketing perspective. Australasian Mark J 28(3):4–13

Lim WM (2022) Ushering a new era of Global Business and Organizational Excellence: Taking a leaf out of recent trends in the new normal. Global Bus Organizational Excellence 41(5):5–13

Lim WM, Rasul T (2022) Customer engagement and social media: Revisiting the past to inform the future. J Bus Res 148:325–342

Lim WM, Weissmann MA (2021) Toward a theory of behavioral control. J Strategic Mark. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2021.1890190 (in press)

Lim WM, Kumar S, Ali F (2022a) Advancing knowledge through literature reviews: ‘What’, ‘why’, and ‘how to contribute’. Serv Ind J 42(7–8):481–513

Lim WM, Rasul T, Kumar S, Ala M (2022b) Past, present, and future of customer engagement. J Bus Res 140:439–458

Lim WM, Yap SF, Makkar M (2021) Home sharing in marketing and tourism at a tipping point: What do we know, how do we know, and where should we be heading? J Bus Res 122:534–566

López-Duarte C, González-Loureiro M, Vidal-Suárez MM, González-Díaz B (2016) International strategic alliances and national culture: Mapping the field and developing a research agenda. J World Bus 51(4):511–524

Mas-Tur A, Kraus S, Brandtner M, Ewert R, Kürsten W (2020) Advances in management research: A bibliometric overview of the Review of Managerial Science. RMS 14(5):933–958

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Reviews 4(1):1–9

Mukherjee D, Kumar S, Donthu N, Pandey N (2021) Research published in Management International Review from 2006 to 2020: A bibliometric analysis and future directions. Manage Int Rev 61:599–642

Mukherjee D, Kumar S, Mukherjee D, Goyal K (2022a) Mapping five decades of international business and management research on India: A bibliometric analysis and future directions. J Bus Res 145:864–891

Mukherjee D, Lim WM, Kumar S, Donthu N (2022b) Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. J Bus Res 148:101–115

Obradović T, Vlačić B, Dabić M (2021) Open innovation in the manufacturing industry: A review and research agenda. Technovation 102:102221

Ojong N, Simba A, Dana LP (2021) Female entrepreneurship in Africa: A review, trends, and future research directions. J Bus Res 132:233–248

Palmatier RW, Houston MB, Hulland J (2018) Review articles: Purpose, process, and structure. J Acad Mark Sci 46(1):1–5

Post C, Sarala R, Gatrell C, Prescott JE (2020) Advancing theory with review articles. J Manage Stud 57(2):351–376

Pranckutė R (2021) Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications 9(1):12

R Core Team (2021) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/ Accessed 20th July 2022

Rovelli P, Ferasso M, De Massis A, Kraus S(2021) Thirty years of research in family business journals: Status quo and future directions.Journal of Family Business Strategy,100422

Salmony FU, Kanbach DK (2022) Personality trait differences across types of entrepreneurs: a systematic literature review. RMS 16:713–749

Snyder H (2019) Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J Bus Res 104:333–339

Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P (2003) Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br J Manag 14(3):207–222

Ulker-Demirel E, Ciftci G (2020) A systematic literature review of the theory of planned behavior in tourism, leisure and hospitality management research. J Hospitality Tourism Manage 43:209–219

Van Eck NJ, Waltma L (2014) CitNetExplorer: A new software tool for analyzing and visualizing citation networks. J Informetrics 8(4):802–823

Vlačić B, Corbo L, Silva e, Dabić M (2021) The evolving role of artificial intelligence in marketing: A review and research agenda. J Bus Res 128:187–203

Wong D (2018) VOSviewer. Tech Serv Q 35(2):219–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317131.2018.1425352

Download references

Open access funding provided by Libera Università di Bolzano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Economics & Management, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Bolzano, Italy

Sascha Kraus

Department of Business Management, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

School of Business, Lappeenranta University of Technology, Lappeenranta, Finland

Matthias Breier

Sunway University Business School, Sunway University, Sunway City, Malaysia

Weng Marc Lim

Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia

Marina Dabić

School of Economics and Business, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia

Department of Management Studies, Malaviya National Institute of Technology Jaipur, Jaipur, India

Satish Kumar

Faculty of Business, Design and Arts, Swinburne University of Technology, Kuching, Malaysia

Weng Marc Lim & Satish Kumar

Chair of Strategic Management and Digital Entrepreneurship, HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management, Leipzig, Germany

Dominik Kanbach

School of Business, Woxsen University, Hyderabad, India

College of Business, The University of Akron, Akron, USA

Debmalya Mukherjee

Department of Engineering, University of Messina, Messina, Italy

Vincenzo Corvello

Department of Finance, Santiago de Compostela University, Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Juan Piñeiro-Chousa

Rowan University, Rohrer College of Business, Glassboro, NJ, USA

Eric Liguori

School of Engineering Design, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia, Spain

Daniel Palacios-Marqués

Department of Management and Quantitative Studies, Parthenope University, Naples, Italy

Francesco Schiavone

Paris School of Business, Paris, France

Department of Management, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

Alberto Ferraris

Department of Management and Economics & NECE Research Unit in Business Sciences, University of Beira Interior, Covilha, Portugal

Cristina Fernandes & João J. Ferreira

Centre for Corporate Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Loughborough University, Loughborough, UK

Cristina Fernandes

Laboratory for International and Regional Economics, Graduate School of Economics and Management, Ural Federal University, Yekaterinburg, Russia

School of Business, Law and Entrepreneurship, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sascha Kraus .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Kraus, S., Breier, M., Lim, W.M. et al. Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice. Rev Manag Sci 16 , 2577–2595 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00588-8

Download citation

Received : 15 August 2022

Accepted : 07 September 2022

Published : 14 October 2022

Issue Date : November 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00588-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Literature reviews

- Bibliometrics

- Meta Analysis

- Contributions

JEL classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Tutorial: Evaluating Information: Peer Review

- Evaluating Information

- Scholarly Literature Types

- Primary vs. Secondary Articles

- Peer Review

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analysis

- Gray Literature

- Evaluating Like a Boss

- Evaluating AV

Types of scholarly literature

You will encounter many types of articles and it is important to distinguish between these different categories of scholarly literature. Keep in mind the following definitions.

Peer-reviewed (or refereed): Refers to articles that have undergone a rigorous review process, often including revisions to the original manuscript, by peers in their discipline, before publication in a scholarly journal. This can include empirical studies, review articles, meta-analyses among others.

Empirical study (or primary article): An empirical study is one that aims to gain new knowledge on a topic through direct or indirect observation and research. These include quantitative or qualitative data and analysis. In science, an empirical article will often include the following sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion.

Review article: In the scientific literature, this is a type of article that provides a synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. These are useful when you want to get an idea of a body of research that you are not yet familiar with. It differs from a systematic review in that it does not aim to capture ALL of the research on a particular topic.

Systematic review: This is a methodical and thorough literature review focused on a particular research question. It's aim is to identify and synthesize all of the scholarly research on a particular topic in an unbiased, reproducible way to provide evidence for practice and policy-making. It may involve a meta-analysis (see below).

Meta-analysis: This is a type of research study that combines or contrasts data from different independent studies in a new analysis in order to strengthen the understanding of a particular topic. There are many methods, some complex, applied to performing this type of analysis.

Peer Reviewed Article vs. Review Article

TIP : Review articles and Peer-reviewed articles are not the same thing! Review articles synthesize and analyze the results of multiple studies on a topic; peer-reviewed articles are articles of any kind that have been vetted for quality by an expert or number of experts in the field. The bibliographies of review articles can be a great source of original, peer-reviewed empirical articles.

Peer Review in Three Minutes

Watch this 3 minute intro to peer review video by North Carolina State University or read this short introduction by the University of Texas at Austin Library.

Is It Peer-Reviewed & How Can I Tell?

There are a couple of ways you can tell if a journal is peer-reviewed:

- If it's online, go to the journal home page and check under About This Journal. Often the brief description of the journal will note that it is peer-reviewed or refereed or will list the Editors or Editorial Board.

- Go to the database Ulrich's and do a Title Keyword search for the journal. If it is peer-reviewed or refereed, the title will have a little umpire shirt symbol by it.

- BE CAREFUL! A journal can be refereed/peer-reviewed and still have non-peer reviewed articles in it. Generally if the article is an editorial, brief news item or short communication, it's not been through the full peer-review process. Databases like Web of Knowledge will let you restrict your search only to articles (and not editorials, conference proceedings, etc).

Checking Peer Review in Ulrich's

Using Ulrich's Periodicals Directory to Verify Peer Review of Your Journal Title

To use this, click on the Ulrich's link to enter the database (or search for it on the main library website).

Change the Quick Search dropdown menu to Title (Keyword) and type your full journal title (not your article title or keywords) into the Quick Search box, then click Search.

This will give you a list of journal titles which includes the title you typed in. Check the Legend in the upper right corner to view the Refereed symbol ("refereed" is another term for peer-reviewed.) Then check your journal title to make sure it has the refereed symbol next to it.

NOTE: Though a journal can be peer-reviewed, letters to the editor and news reports in those same scientific journals are not! Make sure your article is a primary research article.