Background Essay: Gaining the Right to Vote

Directions:

Keep these discussion questions in mind as you read the background essay, making marginal notes as desired. Respond to the reflection and analysis questions at the end of the essay.

Discussion Questions

- How had the work of women to end slavery helped them develop skills that would ultimately be useful in the women’s suffrage struggle?

- What might be meant by the term, “the conscience of the nation,” and how did the fight against slavery help demonstrate that concept?

- What arguments might have been made against women’s suffrage?

- Why were Western states the first to grant suffrage to women?

Introduction

After the Civil War, the nation was finally poised to extend the promise of liberty expressed in the Declaration of Independence to newly emancipated African Americans. But the women’s suffrage movement was split: Should women push to be included in the Fifteenth Amendment? Should they wait for the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to be adopted before turning to women’s suffrage, or should they seize the moment and demand the vote now? Not content to wait, Susan B. Anthony and other workers in the movement engaged in civil disobedience to wake the conscience of a nation. Meanwhile, railroads opened the West to settlement, and Western territories tried to boost population by offering votes for women.

Life for women in the mid-nineteenth century was as diverse as it is now. What was considered socially appropriate behavior for women varied widely across the country, based on region, social class, and other factors. Branches of the women’s suffrage movement disagreed regarding tactics, and some women (and many men) did not even believe women’s suffrage was appropriate or necessary. Ideals of the Cult of Domesticity, in which women were believed to possess the natural virtues of piety, purity, domesticity, and submissiveness, were still a powerful influence on culture. An important debate and split in the women’s suffrage movement between a state and national strategy emerged during this period.

The Cult of True Womanhood

The Cult of Domesticity, also known as the Cult of True Womanhood, affirmed the idea that natural differences between the sexes meant women, especially those of the upper and middle classes, were too delicate for work outside the home. According to this view, such women were more naturally suited to parenting, teaching, and making homes, which were their natural “sphere,” happy and peaceful for their families. In other words, it was unnatural and unladylike for women to work outside the home.

Educator and political activist Catharine Beecher wrote in 1871, “Woman’s great mission is to train immature, weak, and ignorant creatures [children] to obey the laws of God . . . first in the family, then in the school, then in the neighborhood, then in the nation, then in the world.” For Beecher and other writers, the role of homemaker was held up as an honored and dignified position for women, worthy of high esteem. Their contribution to public life would include managing the home in a manner that would support their husbands. According to this conception of the roles of men and women, men were considered to be exhausted, soiled, and corrupted by their participation in work and politics, and needed a peaceful, pure home life to enable them to recover their virtue.

Increasingly, women found their political voice through their work in social reform movements. Jane Addams, co-founder with Helen Gates Starr of Hull House and pioneer of social work in America, wrote in 1902, “The sphere of morals is the sphere of action . . . It is well to remind ourselves, from time to time, that ‘Ethics’ is but another word for ‘righteousness . . . ’” She noted that, to solve problems related to the needs of children, public health, and other social concerns that affected the home, women needed the vote.

In keeping with the feminine ideals of piety and purity, many women continued work within the temperance movement to campaign against the excesses of drunkenness. This cause was considered a socially permissible moral effort through which women could participate in public life, because of the damaging effects of alcohol abuse on the family. Annie Wittenmyer, a social reformer and war widow from Ohio who had reported on terrible hospital conditions during the Civil War, founded the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1874 to build support for the idea of abstaining from alcohol use.

According to the tradition of Republican Motherhood, education should prepare girls to become mothers who raised educated citizens for the republic. In a challenge to the Cult of Domesticity, the latter half of the nineteenth century saw an expansion of broader academic opportunities for upper class females of college age in the United States. In the Northeast, liberal arts schools modeled after Wesleyan College (1836) in Macon, Georgia, opened. In 1844, Hillsdale College opened in Michigan, one of the first American colleges whose charter prohibited any discrimination based on race, religion, or sex. Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, founded in 1861, and Wellesley College in Wellesley, Massachusetts, founded in 1875, also expanded educational opportunities for women. Teaching was among the first professions women entered in large numbers. During and after the Civil War, new opportunities also developed for women to become nurses.

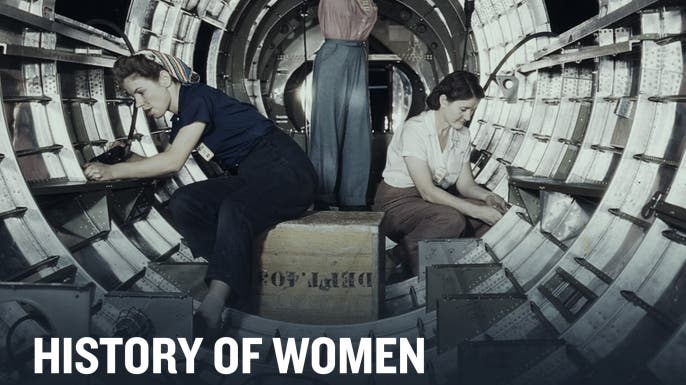

New York City — The sewing-room at A.T. Stewart’s, between Ninth and Tenth Streets, Broadway and Fourth Avenue / Hyde, 1875. Library of Congress.

The Changing Roles of Women

While these career options did not radically challenge the cultural ideal of traditional womanhood, the work landscape of America was changing. As the United States economy grew to provide more options, people began to see themselves as consumers as well as producers. Indeed, mass consumerism drove new manufacturing methods. During the second industrial revolution, the United States started moving from an agricultural economy toward incorporating new modes of production, manufacturing, and consumer behavior.

Young working-class women worked in the same laundries, factories, and textile mills as poor and immigrant men, often spending twelve hours a day, seven days a week, in hot, dangerous conditions. Also, women found work as store clerks in the many new department stores that opened to sell factory-made clothing and other mass-produced items.

The Suffrage Movement Grows

Women continued to work to secure their right to vote. The Civil War ended in April of 1865 and the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified eight months later, banning slavery throughout the United States. A burning question remained: How would the rights of former slaves be protected? As the nation’s attention turned to civil rights and voting with the debates surrounding the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, many women hoped to seize the opportunity to gain the vote alongside African American men.

The Civil War had forced women’s suffrage advocates to pause their efforts toward winning the vote, but in 1866 they came together at the eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention in New York. The group voted to call itself the American Equal Rights Association and work for the rights of all Americans. Appealing to the Cult of Domesticity, they argued that giving women the vote would improve government by bringing women’s virtues of piety and purity into politics, resulting in a more civilized, “maternal commonwealth.”

The Movement Splits

The American Equal Rights Association seemed poised for success with such well-known leaders as Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, and Frederick Douglass. But internal divisions soon became clear. Whose rights should be secured first? Some, especially former abolitionist leaders, wanted to wait until newly emancipated African American men had been given the vote before working to win it for women. Newspaper editor Horace Greeley urged, “This is a critical period for the Republican Party and the life of our Nation . . . I conjure you to remember that this is ‘the negro’s hour,’ and your first duty now is to go through the State and plead his claims.” Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe agreed.

But for Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the time for women also was now. Along with many others, they saw the move to put the cause of women’s suffrage on hold as a betrayal of both the principles of equality and republicanism. Frederick Douglass, who saw suffrage for African American men as a matter of life or death, challenged Anthony on this question, asking whether she believed granting women the vote would truly do anything to change the inequality under law between the sexes. Without missing a beat, Anthony responded:

“ It will change the nature of one thing very much, and that is the dependent condition of woman. It will place her where she can earn her own bread, so that she may go out into the world an equal competitor in the struggle for life.”

In the wake of this bitter debate, not one but two national organizations for women’s suffrage were established in 1869. Stone and Blackwell founded the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Worried that the Fifteenth Amendment would not pass if it included votes for women, the AWSA put their energy into convincing the individual states to give women the vote in their state constitutions. Anthony and Stanton founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). They worked to win votes for women via an amendment to the U.S. Constitution at the same time as it would protect the right of former slaves to vote. Anthony and Stanton started the NWSA’s newspaper, The Revolution, in 1868. Its motto was, “Men, their rights, and nothing more; women, their rights, and nothing less.”

The NWSA was a broad coalition that included some progressives who questioned the fitness of African Americans and immigrants to vote because of the prevailing views of Social Darwinism. The racism against black males voting was especially prevalent in the South where white women supported women’s suffrage as a means of preserving white supremacy. In addition, throughout the country strong sentiment reflected the view that any non-white or immigrant individual was racially inferior and too ignorant to vote. In this vein, Anthony and Stanton used racially charged language in advocating for an educational requirement to vote. Unfortunately for many, universal suffrage challenged too many of their assumptions about the prevailing social structure.

Photograph of Lucy Stone between 1840 and 1860. Library of Congress.

The New Departure: Testing the Fourteenth Amendment

But there was another amendment which interested NWSA: the Fourteenth. In keeping with NWSA’s more confrontational approach, Anthony decided to test the meaning of the newly ratified Fourteenth Amendment. The Amendment stated in part, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States…” Anthony thought it was clear that this language protected the right of women to vote. After all, wasn’t voting a privilege of citizens?

The Fourteenth Amendment went on to state that representation in Congress would be reduced for states which denied the vote to male inhabitants over 21. In other words, states could choose to deny men over 21 the vote, but they would be punished with proportionally less representation (and therefore less power) in Congress. So in the end, the Fourteenth Amendment encouraged states to give all men over 21 the vote, but did not require it. The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, banned states from denying the vote based on race, color, or having been enslaved in the past.

Susan B. Anthony on Trial

It was the Fourteenth Amendment’s protection of “privileges or immunities” that Anthony decided to test. On November 5, 1872, she and two dozen other women walked into the local polling place in Rochester, New York, and cast a vote in the presidential election. (Anthony voted for Ulysses S. Grant.) She was arrested and charged with voting in a federal election “without having a lawful right to vote.”

Before her trial, 52-year-old Anthony traveled all over her home county giving a speech entitled “Is it a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?” In it, she called on all her fellow citizens, from judges to potential jurors, to support equal rights for women.

At her trial, Anthony’s lawyer pointed out the unequal treatment under the law:

“ If this same act [voting] had been done by her brother, it would have been honorable. But having been done by a woman, it is said to be a crime . . . I believe this is the first instance in which a woman has been arraigned [accused] in a criminal court merely on account of her sex.”

The judge refused to let Anthony testify in her own defense, found her guilty of voting without the right to do so, and ordered her to pay a $100 fine. Anthony responded:

“ In your ordered verdict of guilty, you have trampled underfoot every vital principle of our government. My natural rights, my civil rights, my political rights, my judicial rights are all alike ignored . . . I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty. And I shall earnestly and persistently continue to urge all women.” She concluded by quoting Thomas Jefferson: “Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.”

Anthony’s case did not make it all the way to the Supreme Court. However, the Court did rule three years later in a different case, Minor v. Happersett (1875), that voting was not among the privileges or immunities of citizens and the Fourteenth Amendment did not protect a woman’s right to vote.

A caricature of Susan B. Anthony that appeared in a New York newspaper right before her trial. Thomas Wust, June 5, 1873. Library of Congress.

Suffrage in the West

While Anthony and other suffragists were agitating in the Northeast, railroads had helped open up the Great Plains and the American West to settlement. The Gold Rush of 1849 had enticed many thousands of settlers to the rugged West, and homesteading pioneers continued to push the frontier. These territories (and later states), were among the first to give women the right to vote: Wyoming Territory in 1869, followed by Utah Territory (1870), and Washington Territory (1883).

These territories had many reasons for extending suffrage to women, most related to the need to increase population. They would need to meet minimum population requirements to apply for statehood, and the free publicity they would get for giving women the vote might bring more people. And they did not just need more people—they needed women: There were six males for every female in some places. Some were motivated to give white women the vote to offset the influence of African American votes. And finally, there were, of course, those who genuinely believed that giving women the vote was the right thing to do.

Though several western legislatures had considered proposals to give women the vote since the 1850s, in 1869 Wyoming became the first territory to give women full political rights, including voting and eligibility to hold public office. In 1870, Louisa Garner Swain was the first woman in Wyoming to cast a ballot, and a life-sized statue honors her memory in Laramie.

Under territorial government, Wyoming’s population had grown slowly and most people lived on ranches or in small towns. Territorial leaders believed Wyoming would be more attractive to newcomers once statehood was achieved, as had been the case in other western states. The territory came close to reaching the threshold of 60,000 people for statehood, but many doubted whether that number had actually been reached.

Territorial Governor Francis E. Warren refused to wait for more people to move there. He set in motion the plans for a constitutional convention. Though they had the right to do so, no women ran for seats at the Wyoming constitutional convention. Borrowing passages from other state constitutions, delegates quickly drafted the constitution in September 1889. The new element of this constitution is that it enshrined the protections of women’s political rights by simply stating that equality would exist without reference to gender. Only one delegate, Louis J. Palmer, objected to women’s suffrage. Wyoming voters approved the document in November, and the territory applied for statehood.

In the House of Representatives there was some opposition, mostly from Democrats, because the territory was known to lean Republican. Debate did not openly center on party affiliation, but on a combination of doubts about whether Wyoming had truly achieved the required population and on reluctance to admit a state where women had political rights. In response, Wyoming’s legislature sent a telegram: “We will remain out of the Union a hundred years rather than come in without our women!” Wyoming officially joined the union in 1890, becoming the 44th state. Anthony praised Wyoming for its adherence to the nation’s Founding principles: “Wyoming is the first place on God’s green earth which could consistently claim to be the land of the free!”

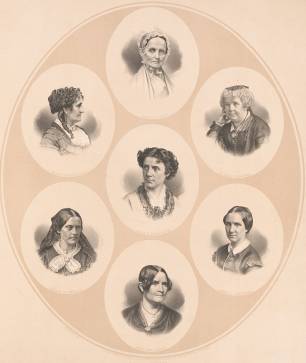

Representative Women, seven prominent figures of the suffrage and women’s rights movement. Clockwise from the top: Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mary Livermore, Lydia Marie Child, Susan B. Anthony, Grace Greenwood, and Anna E. Dickinson (center). L. Schamer; L. Prang & Co. publisher, 1870. Library of Congress.

REFLECTION AND ANALYSIS QUESTIONS

- What was the Cult of True Womanhood, or Cult of Domesticity?

- How did the Industrial Revolution challenge the notion that upper- and middle-class women’s bodies were too delicate for work outside the home?

- Describe the events leading to the split in the women’s movement in 1869.

- What are some actions in which Susan B. Anthony worked for the cause of women’s suffrage in a very personal way?

- The Fourteenth Amendment is ratified

- Susan B. Anthony is jailed for voting

- Western territories give women the vote

- Other (explain)

- Principles: equality, republican/representative government, popular sovereignty, federalism, inalienable rights, freedom of speech/press/assembly

- Virtues: perseverance, contribution, moderation, resourcefulness, courage, respect, justice

03 Nov 2001 Susan B. Anthony on a Woman’s Right to Vote – 1873

Woman’s Rights to the Suffrage

by Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906)

This speech was delivered in 1873, after Anthony was arrested, tried and fined $100 for voting in the 1872 presidential election.

Friends and Fellow Citizens: I stand before you tonight under indictment for the alleged crime of having voted at the last presidential election, without having a lawful right to vote. It shall be my work this evening to prove to you that in thus voting, I not only committed no crime, but, instead, simply exercised my citizen’s rights, guaranteed to me and all United States citizens by the National Constitution, beyond the power of any State to deny.

The preamble of the Federal Constitution says:

“We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people–women as well as men. And it is a downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government–the ballot.

For any State to make sex a qualification that must ever result in the disfranchisement of one entire half of the people is to pass a bill of attainder, or an ex post facto law, and is therefore a violation of the supreme law of the land. By it the blessings of liberty are for ever withheld from women and their female posterity. To them this government has no just powers derived from the consent of the governed. To them this government is not a democracy. It is not a republic. It is an odious aristocracy; a hateful oligarchy of sex; the most hateful aristocracy ever established on the face of the globe; an oligarchy of wealth, where the right govern the poor. An oligarchy of learning, where the educated govern the ignorant, or even an oligarchy of race, where the Saxon rules the African, might be endured; but this oligarchy of sex, which makes father, brothers, husband, sons, the oligarchs over the mother and sisters, the wife and daughters of every household–which ordains all men sovereigns, all women subjects, carries dissension, discord and rebellion into every home of the nation.

Webster, Worcester and Bouvier all define a citizen to be a person in the United States, entitled to vote and hold office.

The only question left to be settled now is: Are women persons? And I hardly believe any of our opponents will have the hardihood to say they are not. Being persons, then, women are citizens; and no State has a right to make any law, or to enforce any old law, that shall abridge their privileges or immunities. Hence, every discrimination against women in the constitutions and laws of the several States is today null and void, precisely as in every one against Negroes.

The National Center for Public Policy Research is a communications and research foundation supportive of a strong national defense and dedicated to providing free market solutions to today’s public policy problems. We believe that the principles of a free market, individual liberty and personal responsibility provide the greatest hope for meeting the challenges facing America in the 21st century. Learn More About Us Subscribe to Our Updates

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The woman suffrage movement in the united states.

- Rebecca J. Mead Rebecca J. Mead Department of History, Northern Michigan University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.17

- Published online: 28 March 2018

Woman suffragists in the United States engaged in a sustained, difficult, and multigenerational struggle: seventy-two years elapsed between the Seneca Falls convention (1848) and the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment (1920). During these years, activists gained confidence, developed skills, mobilized resources, learned to maneuver through the political process, and built a social movement. This essay describes key turning points and addresses internal tensions as well as external obstacles in the U.S. woman suffrage movement. It identifies important strategic, tactical, and rhetorical approaches that supported women’s claims for the vote and influenced public opinion, and shows how the movement was deeply connected to contemporaneous social, economic, and political contexts.

- woman suffrage

- voting rights

- women’s rights

- women’s movements

- constitutional amendments

Winning woman suffrage in the United States was a long, arduous process that required the dedication and hard work of several generations of women. Before the Civil War, most activists were radical pioneers frequently involved in the antislavery or other reform movements. Later, educational advances and the growth of the women’s-club movement mobilized large numbers of middle-class women, while wage work and trade-union participation galvanized working-class women. In the early 20th century , woman suffrage became a mass movement that effectively utilized modern publicity and outreach methods. Woman suffrage was never a “gift.” Skillful organization, mobilization, and activism were required to build a powerful social movement and achieve the long-sought goal.

Woman suffrage was a radical idea in the 19th century . Suffrage for non-elite white men was still limited in most countries and became the norm in the United States only in the decades before the Civil War—a time when women and people of color were considered deficient in the rational capacities and independent judgment necessary for responsible citizenship. Woman suffrage challenged the legal principle of coverture, which subsumed a married woman’s political and economic identity into her husband’s; it also challenged dominant gender roles that confined women to the domestic sphere. Additionally, suffragists often associated themselves with other radical or reformist political groups who supported the demand as a basic right, a strategy for enhancing democracy, or a practical way to gain allies.

Women’s Status and Women’s Rights in the New Republic

Prior to the American Revolution, property restrictions limited even white male suffrage. Yet some colonial women voted if they paid taxes, owned property, or functioned as independent heads of households, although this was uncommon. The idea of universal suffrage (i.e., voting rights for all citizens) arose from the democratic ideology of the Enlightenment. Revolutionary rhetoric did not automatically result in equal citizenship rights, but it did provide powerful philosophical arguments that supported future struggles. In 1776 , New Jersey enfranchised “all inhabitants” who were worth “fifty pounds” and had resided in the county for a year prior to an election. Coverture still prevented married New Jersey women from voting. But especially after 1797 , unmarried women voted with enough frequency to generate complaints about “petticoat electors” who played critical roles in contested elections, and in 1807 New Jersey disenfranchised women altogether as well as African Americans and aliens. 1

The American Revolution gave rise to the ideal of the “Republican Mother” who educated her children to become future citizens and exerted beneficial moral influences within her family, an ideal that ultimately held important implications for citizenship and voting. To meet the new country’s need for responsible citizens, many schools were established for women (although they did not meet the standards of comparable men’s schools), while the expansion of public elementary education increased the demand for female teachers. By definition, women farmers, slaves, textile-mill operatives, and indigents could not meet emerging middle-class norms of female domesticity. 2

Rapid economic, political, and social change exacerbated prostitution, excessive alcohol consumption, and other problems associated with poverty, particularly in the urbanizing northeast. In response, some urban middle-class women became involved in “moral reform” societies, the most significant of which was the antislavery movement. Both white and African American abolitionist women formed female antislavery societies, but they were criticized when they assumed public roles. Most famously, when Sarah and Angelina Grimké, the transplanted daughters of a slave owner, began to speak before large mixed-race and mixed-sex (“promiscuous”) audiences, they were harshly, even violently, attacked. When the Massachusetts Council of Congregational Ministers issued a pastoral letter in 1837 denouncing their behavior as unwomanly, the sisters responded by defending equality of conscience, emphasizing the importance of female participation in the abolitionist movement, and drawing parallels between slavery and the disadvantaged status of women. 3

The Seneca Falls Convention and the Beginnings of an Organized Women’s Movement

Elizabeth Cady was already deeply embedded in various reform networks in upstate New York when she married fellow activist Henry Stanton and accompanied him to London to attend the World Anti-Slavery Conference in 1840 . At the meeting, a fierce debate erupted over seating female delegates, and the women were forced to retreat to the gallery, where William Lloyd Garrison, the most prominent and radical of the American abolitionists, joined them in protest. Furious, Stanton discussed this injustice with another attendee, Quaker reformer Lucretia Mott, and the two conceived the idea of holding a women’s-rights convention. For the next few years, Stanton was preoccupied with her growing family, but she and Mott met again in 1848 and decided to organize a women’s-rights convention in the small town of Seneca Falls. They placed an announcement in the local newspaper and were astonished when 300 people showed up (including 40 men, most notably Frederick Douglass, a former slave and the country’s most prominent black abolitionist). Stanton opened the meeting by reading the “Declaration of Sentiments,” a document she had prepared by adapting the Declaration of Independence to address women’s issues. Stanton listed many grievances, including lack of access to education, employment opportunities, and an independent political voice for women. Companion resolutions were all approved unanimously except the demand for woman suffrage, which passed by a small margin after a vigorous discussion. The convention at Seneca Falls is traditionally seen as the beginning of the American women’s-rights movement, as well as launching Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s long career as its premier intellectual force. The enthusiasm generated at Seneca Falls quickly led to more women’s-rights conventions. Beginning in 1850 , similar gatherings were held nearly every year of the decade. 4

Conventions and new women’s-rights publications, including The Lily (Amelia Bloomer) and The Una (Paulina Wright Davis), helped activists stay in contact, discuss ideas, develop leadership skills, gain publicity, and attract new recruits, including Susan B. Anthony, a Quaker, temperance activist, and abolitionist. Initial efforts focused on convincing state legislatures to rectify married women’s legal disadvantages with regard to property rights, child guardianship, and divorce. In 1854 , Anthony traveled throughout New York State, organized a petition drive, planned a women’s-rights convention, and secured a hearing before the legislature that was addressed by Stanton. Thus Anthony and Stanton began their fifty-year partnership.

1a. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, ca 1891. Their partnership lasted for over 50 years, although neither lived to see the final accomplishment of their goal.

1b. “The Apotheosis of Suffrage” (1896). Stanton and Anthony’s founding role in the women rights movements is acknowledged by their elevation to the national pantheon by their NAWSA colleagues.

Other important early white activists included Lucy Stone, Abby Kelley Foster, Matilda Joslyn Gage, Clarina Howard Nichols, and Frances Gage. Important African American suffragists included Sojourner Truth, Sarah Redmond, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Amelia Shadd, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, Harriet Forten Purvis, Charlotte Forten, and Margaretta Forten. 5 The early women’s-rights movement included both black and white activists, yet relations sometimes became tense when white women ignored or appropriated African American experiences to suit their own purposes. For example, at a women’s-rights convention in 1851 , Sojourner Truth made brief remarks describing the hard work of slave women and citing religious examples to support women’s rights. Some accounts report resistance to allowing Truth to speak and introducing slavery references, but convention president Frances Gage intervened. Gage subsequently edited and reported Truth’s speech in the form of the famous “Ain’t I a Woman” version, which is problematic in its use of dialect and other editorial interventions. 6 After the Civil War, connections between race and gender equity became more problematic as racial attitudes hardened. Racial violence escalated during Reconstruction and continued for decades, while legal discrimination became firmly entrenched, legitimated by scientific racialist theories.

Reconstruction, Civil Rights, and Woman Suffrage

Women’s-rights advocates interrupted their efforts during the Civil War to concentrate on war work, but subsequent debates over the Reconstruction Amendments created new opportunities to reintroduce demands for women’s enfranchisement. Woman suffragists objected strenuously when the Fourteenth Amendment defined national citizenship and voting requirements by introducing the word “male” into the Constitution for the first time. The Fifteenth Amendment established the right of freed black men to vote, but failed to extend the vote to any women, creating a controversy that split the suffrage movement. Some suffragists, including Lucy Stone, her husband and fellow reformer Henry Blackwell, and most (but not all) prominent black activists supported the Fifteenth Amendment, arguing that black men needed the vote more urgently than women did, and expressing concerns that woman suffrage might prevent the amendment from passing. Stanton and Anthony vehemently disagreed and publicly opposed the amendment as they continued to demand universal suffrage. The American Equal Rights Association (AERA), organized in 1866 to promote both causes, supported the Reconstruction Amendments, and proposed the submission of a separate woman-suffrage amendment, first introduced as a Senate resolution in December 1868 . 7

In 1867 , the AERA became involved in two Kansas state suffrage referenda relating to woman and African American suffrage amendments. Stone, Blackwell, Stanton, and Anthony all actively participated, but the growing rift among suffragists soon became evident. The AERA tried to link the issues of black and women’s rights, but suffragists were disappointed when the Republican Party publicly opposed the woman-suffrage referendum. Stanton and Anthony’s overtures to dissenting Democrats—especially George Francis Train, an Irish Democrat, controversial financier, and outspoken racist, generated additional controversy. After a bitter struggle, the Kansas referenda for woman and black suffrage both failed. This crucial campaign effectively severed the connection between voting rights for blacks and women. 8

Convinced by their Kansas experiences that male political support was unreliable, Stanton and Anthony established the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), an independent women’s-rights organization under female leadership, in 1869 . Several months later, Stone, Blackwell, Julia Ward Howe, and others established the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Initially these two groups pursued different strategies. A federal woman-suffrage amendment seemed unlikely to pass, so the AWSA concentrated on changing state constitutions. The NWSA articulated a broader women’s-rights agenda and sought suffrage at the federal level. The two organizations worked independently until they merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1890 . Each group published a women’s-rights journal. With Train’s financial backing, Anthony founded The Revolution early in 1868 and published many articles related to the problems of working women, prostitution, the sexual double standard, discriminatory divorce laws, criticisms of established religion, and denunciations of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. The Revolution was very influential but unable to compete with the Woman’s Journal , introduced by the AWSA in 1870 . Although the Woman’s Journal was widely read until it ceased publication in 1931 , it was only one of many women’s-rights periodicals published during this period. 9

As part of its federal strategy, the NWSA also proposed a bold reinterpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment, the “New Departure,” arguing that suffrage was a right of national citizenship and since women were citizens they should be able to vote. The Revolution urged women to go to their local polls and use the New Departure argument to try to vote, and a few succeeded. Anthony’s own attempt led to her trial and conviction for violating election laws, but she was not punished (except for a $50 fine, which she refused to pay), eliminating the possibility of legal appeal. In 1875 , the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the New Departure, reasoning in Minor v. Happersett . A Missouri suffrage leader, Virginia Minor, had sued the state for the right to vote, but the court unanimously held that while Minor was indeed a citizen, the right to vote was not one of the “privileges and immunities” that the Constitution granted to citizens. 10

The national woman-suffrage organizations were influential, but there were many independent, often regional, journalists and activists who addressed women’s rights during the postwar period. Few were as colorful or sensational as Victoria Woodhull, who addressed the House Judiciary Committee in 1871 —the first woman ever to do so—and made powerful constitutional arguments that persuaded a minority of representatives. Both Woodhull and her sister, Tennessee Claflin, aroused controversy. At various times one or both were journalists, stockbrokers, Spiritualists, and labor activists, but Woodhull’s public advocacy of “free love” generated the most vehement criticism. Her basic position was that the right to divorce, remarry, and bear children should be individual decisions, but most of her contemporaries considered these ideas quite scandalous. Woodhull ran for president in 1872 as the nominee of the Equal Rights party, the first woman to do so. Initially Woodhull received some support from other suffragists, but as her notoriety grew, so did suffragists’ concerns about being compromised by association, and many began to repudiate or distance themselves from her ideas and activities (at least in public). 11

Social Change, Women’s Organizations, and Suffrage in the Late 19th Century

Many women became interested in suffrage through their membership in other activities and organizations, especially as a result of the rapid growth of the women’s-club movement. When the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC) was established in 1890 , it represented 200 groups and 20,000 women; by 1900 , the GFWC claimed 150,000 members. Often initiated for educational or cultural purposes, discussions frequently turned to social issues such as child welfare, temperance, poverty, and public health. Women who became interested in reform soon realized that they had little political influence without the vote. The GFWC did not officially endorse suffrage until 1914 , however, because the diversity of its constituent groups made the subject contentious and consensus difficult.

African American clubwomen, barred from membership in white women’s organizations, formed the National Association of Colored Women in 1896 . In addition to community work and suffrage agitation, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mary Church Terrell, and other prominent black women challenged contemporary negative stereotypes about African Americans and worked to increase public awareness of racial segregation, disfranchisement, and violence.

2. Ida B. Wells-Barnett (L) and Mary Church Terrell (R). Both women were prominent African American journalists and activists. Both were founding members of the NAACP and active in NAWSA. Among their many achievements, Wells-Barnett established the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago, while Terrell was the first president of the National Association of Colored Women.

Many white women were indifferent to these issues, however, and some openly expressed the prejudices of the dominant society in their exclusionary rhetoric and organizational policies. 12

The largest of the many new national women’s organizations was the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), established in 1874 . Under the dynamic leadership of Frances Willard, the WCTU emphasized the impact of alcohol abuse on women and families in its agenda of “home protection,” but quickly adopted a much broader social-welfare program, established alliances with labor and reform groups, and supported woman suffrage as a means to achieve its goals. Liquor-control efforts provoked powerful opposition, leading many woman suffragists to distance themselves publicly from the temperance movement even as they appreciated the dedication of WCTU suffragists. 13

The expansion of women’s opportunities for higher education provided another catalyst for suffrage activism. In addition to the many public agricultural and technical colleges established under the 1862 Morrill Land-Grant Act, the establishment of a number of private women’s colleges began with Vassar in 1861 . Believing that education would be the key to women’s advancement, founders and administrators set high standards and offered curricula very similar to those at men’s institutions. After graduation, many women who found themselves largely excluded from professional training and employment opportunities channeled their skills and energies into civic engagement and social reform, especially with the rapid expansion of the American settlement house movement after the establishment of Hull House in Chicago in 1889 . As community centers located in poor neighborhoods, settlement houses offered a variety of classes and services, but when social workers realized that their efforts alone could not eradicate problems related to chronic poverty, many became active in reform politics. In addition, new protective and industrial associations tried to help impoverished working women living alone in the cities. While middle-class moral judgments often alienated their intended beneficiaries, these efforts began to establish ties with working-class constituencies and labor organizations that would eventually gain support for woman suffrage. 14

As industrial development, urbanization, and immigration increased, the growing numbers of women in the work force provided new arguments for woman suffrage. Working men understood that few working-class women could depend upon adequate male support, but they were hostile to low-wage female competition because it undermined their own abilities to fulfill the dominant male gender role of family breadwinner. The skilled trades and craft unions discouraged or discriminated against women, although the more progressive Knights of Labor included minorities and women. Urban working-class men were understandably reluctant to grant more power to middle-class women who condemned them as dirty, drunken immigrants and/or violent radicals. Their opposition defeated many state campaigns until working-class suffragists began to characterize the vote as a way to protect female wage earners and to empower the working class as a whole. 15

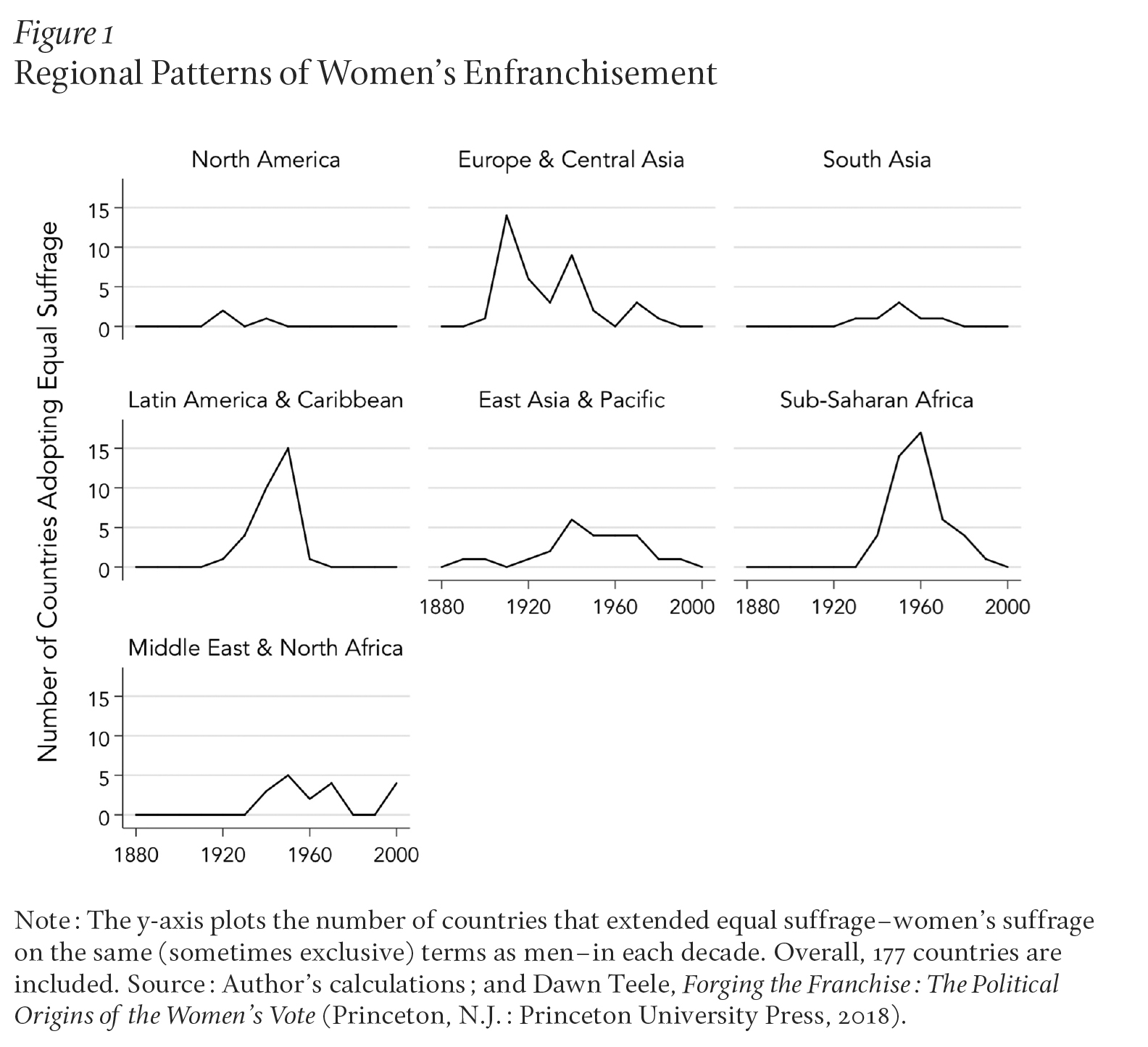

These socioeconomic and political developments would eventually strengthen support for woman suffrage, but suffragists still faced enormous difficulties. Small, poorly funded groups gathered signatures on petitions and lobbied state legislators to authorize public referenda on the right of women to vote. When successful, they faced the daunting challenge of organizing a statewide campaign. Many suffragists were politically inexperienced and criticized for violating prescriptive gender norms, but over time they built organizations, developed management and leadership skills, articulated effective arguments, and learned to maneuver through the political system. They experienced many disappointing defeats in the process: between 1870 and 1910 , seventeen states held referenda on woman suffrage, but most failed. By 1911 , only twenty-nine states allowed some form of partial woman suffrage: school, tax, bond, municipal, primary, or presidential. Partial suffrage was better than nothing, but it reduced the pressure for full suffrage and did not always motivate women to vote; when women did not turn out to vote, opponents asserted that they were not interested in politics. 16

Women Win the Vote in the West

Reviewing the record in 1916 , NAWSA president Carrie Chapman Catt counted 480 state legislative campaigns and forty-one state referenda resulting in only nine state or territorial victories, all in the western United States. 17 Indeed, by the end of 1914 , almost every western state and territory had enfranchised its female citizens.

3. “The Awakening” by Henry Mayer (1915). This poster highlights the significance of the western woman suffrage state victories, which enfranchised four million women in the region and established important examples and precedents.

These western successes stand in profound contrast to the east, where few women voted until after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment ( 1920 ), and to the South, where no women could vote and most African American men were effectively disfranchised. Early explanations attributed this unusual history to a putative “frontier” effect (a combination of greater female freedom and respect for women’s contributions to regional development), or western boosterism (efforts to attract settlers), but these reasons are too simplistic. 18 Western women gained the right to vote largely due to the unsettled state of regional politics, the complex nature of race relations, broad alliances between suffragists and farmer-labor-progressive reformers, and sophisticated activism by western women. The success of woman suffrage required building a strong movement, but it was inseparable from the larger political environment, and the west provided suffragists with unusual opportunities. 19

Initially the territorial status of most western areas gave Congress and tiny territorial legislatures the power to decide who could vote. Every application for statehood required a proposed constitution, and the process always involved debates about voting qualifications. Wyoming Territory surprised the nation by adopting woman suffrage in 1869 , although its reasons for doing so remain unclear since there were some dedicated individuals, but no organized movement and little prior discussion. Most likely, the Democratic legislature hoped to embarrass the Republican governor, who signed the bill partly in deference to his wife. In Utah woman suffrage became entangled in the polygamy controversy. Determined to abolish this practice, some Republicans in the U.S. Congress suggested the enfranchisement of Utah women so that they could vote against polygamy. State Democratic Mormon politicians believed correctly that Utah women would vote to support polygamy and authorized woman suffrage in 1870 . In 1887 , Congress punitively disfranchised all Utah voters until the Mormons repudiated polygamy in 1890 , and the church leadership capitulated. The men of Utah were re-enfranchised in 1893 , but women had to wait until statehood in 1896 . In 1883 , the Washington territorial legislature passed a woman suffrage with bipartisan support, as an experiment which could be corrected, if necessary, when Washington became a state. Feeling threatened, vice and liquor interests organized a series of court challenges until the territorial supreme court finally dismissed the law in 1888 . Delegates to the 1889 constitutional convention refused to include the provision because they feared rejection by Congress, but the convention authorized separate suffrage and prohibition referenda on the ratification ballot. Organizers had little time to prepare for statewide campaigns, and both measures met firm defeat. 20

In the 1890s, the rise of the Populist movement provided the context for the first two successful state referenda in Colorado ( 1893 ) and Idaho ( 1896 ). Largely characterized as a western agrarian insurgency advocating an anti-monopoly and democratization agenda, Populism arose from predecessor organizations, such as the Grange and the Farmers Alliances, in which women were actively involved. At the state level, Populist suffragists had some success convincing their colleagues, but at the national level Populists sacrificed their more radical demands to gain broader support, especially after they merged with the Democratic Party in 1896 . Woman suffrage referenda failed in South Dakota in 1890 , and in Kansas and Washington in 1894 despite energetic efforts. NAWSA organizer Carrie Chapman Catt rose to national prominence as a result of her work in the 1893 Colorado campaign, and in 1896 , Susan B. Anthony personally took charge in California. During these campaigns, Anthony and other suffragists made strenuous and sometimes successful efforts to gain endorsements from political parties, but they already knew from bitter experience that unless all the parties supported the measure, the issue of woman suffrage succumbed to divisive partisanship. 21

Challenges and Opportunities at the Turn of the Century

These disappointments had a chilling effect on the suffrage movement leading to a period sometimes described as “the doldrums.” The older first-generation radicals passed on (Stanton died in 1902 , Anthony in 1906 ), and most of the younger leaders (e.g., Rachel Foster Avery, May Wright Sewall, and Harriet Taylor Upton)—privileged women who shared prevailing notions about proper female behavior and resisted radical public-outreach methods—failed to bring innovative new ideas and strategies to the movement. They also alienated key constituencies by complaining publicly that they could not vote but “inferior” (racial-ethnic, working-class, immigrant) men could. Suffrage leaders used economic arguments focused on the growing population of “self-supporting women,” but they rarely cooperated with working-class women and usually chose avoidance or discrimination over collaboration with African American suffragist colleagues. 22

In the 1890s, NASWA turned its attention to the South. Activists in that region’s nascent movement argued that enfranchising white women would provide a gentler way to maintain white supremacy than the harsh measures being implemented to disfranchise African American men. Anti-black sentiments had marred the suffrage movement for many years. Indeed, Southern suffragists like Kate Gordon and Laura Clay protested that the presence of African American women in the suffrage movement undermined their strategy of enfranchising and mobilizing white women to outvote African Americans in order to preserve white hegemony. Personally uncomfortable with these attitudes, Anthony endeavored to keep the race issue separate from woman suffrage, but she did so by reluctantly endorsing “educated suffrage” (i.e., literacy qualifications) and rejecting appeals for help from black suffragists. She even asked her old friend, Frederick Douglass, not to attend the 1895 NAWSA convention in Atlanta for fear of offending southern suffragists. In New Orleans in 1903 , the NAWSA convention excluded black suffragists and approved of literacy requirements, though it was already clear that this “southern strategy” was not working. In the 1890s, southern states passed many measures to disfranchise black men but firmly rejected woman suffrage even with literacy and other restrictions attached. NAWSA retreated from blatant racism and from hopeless Southern state campaigns, but continued to tolerate segregationist policies within the organization and blocked efforts to address issues of racial injustice. NAWSA’s racist practices persisted throughout the struggle for a federal woman suffrage amendment and into the ratification process partly due to the difficulty of overcoming the implacable opposition of conservative states’ rights Southern politicians. 23

During the 1890s, state anti-suffrage organizations began to form, and the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS) was established in New York in 1911 . Suffragists routinely blamed their losses on the “liquor interests” (although political bosses and manufacturers also worried about the consequences of enfranchising reform-minded women) and dismissed women who opposed suffrage as pawns of these interests, but this was not always the case. Some female anti-suffragists supported reform more broadly, belonged to the same clubs as suffragists, and adopted many of the same innovative public-outreach and mass-marketing techniques. Yet many anti-suffragists opposed enfranchisement because they believed that direct female engagement in the dirty business of party politics and voting would deprive women of their claims to moral superiority and nonpartisanship. 24

Modern Suffragists and the Progressive Movement

By 1900 , a new generation of suffragists was growing impatient with what they perceived as timid leaders and tired, ineffective methods and began to employ more assertive public tactics. It was a period of massive political discontent throughout the entire country as many people felt disoriented by rapid modernization and concerned about its consequences. Ideas that had seemed too radical or regional when articulated by Populists in the 1890s now found mainstream support among middle-class urbanites involved in the Progressive reform movement. In the 1890s, Populism failed as a national political force, but it remained influential locally and regionally and appeared, reincarnated, in western Progressivism. 25 Although similar developments were occurring in the east, politically innovative western environments once again contributed to suffrage success. The breakthrough suffrage victories occurred in Washington state ( 1910 ) and California ( 1911 ), quickly followed by Oregon and Arizona ( 1912 ), and Nevada and Montana ( 1914 ). In Washington state, NAWSA organizer Emma Smith DeVoe became the leader of the state organization. DeVoe stressed the importance of good publicity and systematic canvassing while insisting upon ladylike decorum. Suffragists attended meetings of churches and ethnic associations and won endorsements from farmer and labor groups, often through the activism of working-class women. Those who rejected DeVoe’s leadership or moderate approach worked independently, often organizing parades and large public meetings. In 1910 , the referendum passed in every county and city in Washington state, breathing new life into the movement. 26

In California, where a strong progressive political insurgency won the referendum in 1911 , suffragists organized a massive public campaign. They held large public rallies, used automobiles to give speeches on street corners and in front of factories, produced a flood of printed material utilizing striking designs and colors, and coordinated professional press work. Working-class women organized their own suffrage group, the Wage Earners Suffrage League, while Chinese, Italian, African American, and Latina suffragists also worked within their communities. The NAWSA provided foreign-language literature generated locally by the members of the College Equal Suffrage League. Members of the WCTU worked vigorously but quietly. On election day, volunteers carefully watched polling places to discourage fraud, then held their breath for two days until they learned that the measure had passed by a mere 3,587 votes. They realized that victory would not have been possible without an impressive increase in urban working-class support since the last failed referendum in 1896 . 27

These new campaign tactics were quickly adopted by suffragists in other western states, frequently causing tensions between cautious older women and younger activists. In Oregon, for example, the region’s pioneer veteran suffragist, Abigail Scott Duniway, rejected public campaigns, arguing that they alerted and mobilized powerful opponents (mainly the liquor and vice interests). She insisted upon what she called the “still hunt” approach: quiet lobbying and speaking to groups to gain endorsements. Duniway also antagonized WCTU activists by insisting on a strict separation between suffrage and prohibition, especially if both measures were on the same ballot.

In 1902 , Oregon was the second state to adopt the initiative, a Progressive reform that allowed reformers to bypass uncooperative legislature and place measures directly on the ballot. Oregon suffragists subsequently utilized this process to place woman suffrage before voters every two years, but it did not pass until 1912 after frustrated younger women finally wrested control of the state organization from Duniway and implemented the modern model. 28

By 1915 , all western states and territories except New Mexico had adopted woman suffrage. These successes validated the efficacy of dramatic new tactics and created four million new women voters who could be enlisted to support the revived struggle for the federal amendment. In addition, many experienced western suffragists headed east, where similar developments were occurring, most notably in the rise of the National Woman’s Party, but where the opposition was also better organized and funded.

Catalyzed by the Progressive impetus and the excitement surrounding the 1912 presidential campaign, six states held suffrage referenda that year. Three western successes in Oregon, Kansas, and Arizona were counterbalanced by defeats in Wisconsin, Ohio, and Michigan. In Ohio, the “liquor interests” publicly boasted of defeating the measure; failure in Wisconsin was also attributed to the opposition of the state’s important brewing industry. In Michigan, massive electoral irregularities turned initial reports of victory into a loss (by only 760 votes). In 1914 , two western states approved woman suffrage (Montana and Nevada), but in North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Missouri, and Ohio, hard-fought campaigns resulted in defeat. In 1915 , there were referenda in four major eastern states, New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. If any of these large, urbanized, industrial states passed the measure, the eastern stalemate would be broken, but all failed in spite of massive efforts. The opposition seemed insurmountable in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, where state laws prohibited immediate resubmission, thus suffragists focused on New York, the most heavily industrialized, urbanized, and populated state, and the one with more representatives in Congress than any of the others. 29

The NAWSA Struggles to Keep Up

The still quite frequent assertion that the U.S. suffrage movement was languishing in “the doldrums” during these years rests partly on unquestioned and erroneous assumptions that “the suffrage movement” means events in the east and the activities of the NAWSA. Indeed, the NAWSA leadership seemed to lack the ability to develop more successful strategies and tactics, could not consolidate or focus the energies and innovations of the new generation of suffragists, and were often resistant or openly hostile to their ideas and methods. When Anthony relinquished the NAWSA presidency in 1900 , two women emerged as potential successors, Carrie Chapman Catt and Anna Howard Shaw. For several years, Catt had urged major administrative changes and systematic campaign plans coordinated by a strong central state organization under national supervision. Shaw was an old friend of Anthony who had overcome an impoverished background to earn divinity and medical degrees. She has often been described as a brilliant orator but a poor administrator, but a recent study has challenged this conclusion (while not completely overturning it) by noting that this judgment reflects biases in the original sources and overlooks the growth and diversification of the NAWSA membership, its increasingly sophisticated organizational structure, improved fund-raising techniques, and other significant developments during the decade of Shaw’s leadership. 30 Shaw succeeded Catt as president in 1904 when family health issues forced Catt to “retire,” but she remained actively involved in the international suffrage movement and later reestablished herself on the national scene through her work in New York state.

Transnational connections and influences had been important from the earliest days of the movement. In 1888 , American leaders established the International Council of Women (ICW) hoping to promote international suffrage activism, but were disappointed because the organization avoided controversial issues (like suffrage) to focus on moral reform and pacifism. In 1902 , Catt and other frustrated suffragists established the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA). The topic of transnational suffrage activism has received significant scholarly attention recently, revealing extensive and dynamic connections among suffragists worldwide from the mid-1800s well into the 20th century . 31

By the time Catt returned to the U.S. movement in New York in 1909 , she observed many promising developments, especially the growing numbers of women at work and involved in various social-reform activities. Suffragists used affiliations with labor unions and reform groups to form cross-class suffrage coalitions and to appeal to urban working-class voters. They largely abandoned elitist, nativist, and racist rhetoric (at least in public) and emphasized arguments that linked political rights and economic justice for women of all classes. In New York, Harriot Stanton Blatch (Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter) formed the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women in 1907 , which included experienced women trade unionists and suffragists like Leonora O’Reilly and Rosa Schneiderman. Blatch, a suffragist with strong labor and socialist sympathies, had previously lived in England and formed close associations with the British suffragettes. American suffragists consciously repudiated British militancy and violence, however, preferring clever, creative, and colorful activities that gained public attention and sympathy, like the annual suffrage parades Blatch began organizing in 1910 .

4. Suffrage parade in New York City, 23 Oct. 1915. In the early 1900s, the struggle for woman suffrage became a mass and public movement. Suffragists organized highly visible and colorful events, such as this pre-referendum parade in which 20,000 women marched in clear order to send a clear message of their determined purpose.

The basic demand for equal economic justice did not eliminate internal class conflict, however. Late in 1910 , the Equality League became the Women’s Political Union (WPU), indicating a shift to elite leadership and increasing British influence. In 1911 , O’Reilly left to form a separate Wage Earners’ League for Woman Suffrage. 32

In 1909 , Catt formed the Woman Suffrage Party (WSP) hoping to channel these energies and coordinate the movement under her direction. She soon controlled the state association and consolidated most of the state suffrage groups (with the notable exception of the WPU). After an intense lobbying effort, the legislature authorized a referendum vote in 1915 , and the suffragists mounted a huge campaign over the next ten months. They held thousands of outdoor meetings and events, targeted outreach to crucial constituencies, and flooded the state with literature. Catt’s plans included systematic door-to-door canvassing, which eventually reached over half the state’s voters. On election day, the measure lost by a narrow margin, but within days suffragists raised $100,000 and began the work all over again. After another massive campaign, woman suffrage passed in New York in 1917 by over 100,000 votes. The same year, seven states, including Arkansas, granted some form of partial suffrage. In 1918 , woman-suffrage referenda passed in Michigan, South Dakota, and Oklahoma. The eastern blockade was broken, and the South had begun to crack. 33

While Catt exercised masterful managerial and strategic skills in New York, the NAWSA was having trouble keeping up, and Shaw came under increasing criticism from her NAWSA colleagues. Prominent suffragists such as Katherine McCormick, Harriet Laidlaw, and Jane Addams attempted to fill the perceived leadership gap, but many believed that Catt was the only one with the organizational skills to rescue what she herself described as a “bankrupt concern.” Catt resumed the NAWSA presidency in 1915 and began implementing her ideas for bureaucratic reorganization, legislative and partisan lobbying, and systematic campaigning. The previous year, Catt had secretly introduced her “Winning Plan,” which included winning a few targeted campaigns in the east and South under national direction, gaining party endorsements, and renewing the struggle for a federal amendment. Women voters were instructed to lobby their legislators; suffragists in states where referenda successes were considered possible were to coordinate their efforts under national direction; and the goal in the South was some form of partial suffrage. 34 None of these were new ideas, but Catt brought them together in this master plan, which she eventually implemented with remarkable success, but her hostility to militancy, independent activism, and rival leaders intensified when confronted with a dynamic new force, Alice Paul.

Alice Paul and the Congressional Union

Paul did not single-handedly reinvigorate a moribund U.S. suffrage movement, but she was a brilliant organizer and an inspiring leader who soon attracted a cadre of radical and committed activists frustrated by the apparent conservatism and inefficacy of the NAWSA leadership. Determined to win the federal amendment, they aimed to make life miserable for politicians until they achieved their objective. Paul learned this strategy from the British suffragettes during her involvement with them and transplanted it to the United States. As a Quaker, however, Paul rejected their violent tactics and developed other provocative and militant methods. She had an extraordinary talent for organizing highly public suffrage events. Her spirit was contagious and her goal compelling even for mainstream suffragists opposed to radical tactics.

Early in 1913 , Paul and her friend Lucy Burns revived the NAWSA’s quiescent Congressional Committee, initially with that organization’s blessing, but controversy and schism soon followed. Within two months of their arrival in Washington, DC, they had organized a massive suffrage parade, held on March 3, the day before Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration. When the marchers were attacked by a mob and the police failed to protect them, the suffrage movement gained massive publicity and considerable sympathy. In April, Paul and Burns formed an independent organization, the Congressional Union (CU), quickly gathered 200,000 signatures on petitions, and started lobbying President Wilson and other prominent politicians. Paul lost her position as chair of the NAWSA Congressional Committee at the 1913 convention because she defied the national leadership’s efforts to tame her, and she rejected all subsequent reconciliatory approaches. 35

The split deepened when the CU implemented the British suffragette policy of “holding the party in power responsible” by sending organizers into nine western states to persuade women voters to oppose Democratic candidates during the 1914 election. Although politicians insisted that this effort had no impact on their campaigns, half of them lost, and soon thereafter woman suffrage was reintroduced in Congress for the first time in two decades. The proposed Shafroth-Palmer Amendment was not the “Anthony Amendment,” however, which since 1878 had simply stated that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” The Shafroth-Palmer Amendment defined woman suffrage as a “states’ rights” issue, dictated a return to arduous state campaigns (which had largely been unsuccessful), and allowed discrimination against black women. The current NAWSA Congressional Committee chair, Hannah McCormick, endorsed it without consulting the organization’s board, and the proposal received some support from suffragists who saw no alternative to compromise with the Southern states’ rights bloc in Congress. Most suffragists rejected it, however, and continued to demand action at the federal level. After formally organizing the National Woman’s Party (NWP), Paul’s group reprised their attacks on western Democrats in the 1916 election.

5. “Women of Colorado” (1916). One of the first efforts of the NWP was to “hold the party in power” (i.e., the Democrats) responsible for lack of progress on the woman suffrage amendment. In 1914, their efforts to persuade western women voters to vote against the Democratic party were not very effective, but frightened politicians soon moved the amendment forward in Congress. In 1916, the NWP repeated this operation and posted this billboard.

This tactic infuriated Catt since it undermined her efforts to lobby politicians to gain their support. 36

Suffrage during World War I

When the United States entered the war in April 1917 , neither organization abandoned the suffrage struggle. In spite of earlier pacifist activism by Catt and others, the NAWSA urged women to engage in both war work and suffrage agitation, hoping that patriotic efforts would gain additional public support for the cause. The NWP concentrated exclusively on suffrage, continued using militant tactics, and introduced propaganda ridiculing claims that America could fight for democracy while denying women at home the right to vote. Most famously, in January 1917 the NWP began silent picketing outside the White House. Initially tolerated by the Wilson administration, harassment and violence by onlookers escalated, and in June arrests of the picketers began, ultimately affecting 218 women.

6. Picketing the White House. By August 1917, the Congressional Union (later the NWP) had been silently picketing the White House since January, tensions were running high, and crowd attacks on picketers increased. Arrests had begun in June, followed by months-long prison sentences, for the charge of “obstructing traffic.”

At first, charges were dismissed or sentences minimal, but penalties increased over the next few months. Some of the women began hunger strikes to protest the heavy punishment, bad conditions, and brutal treatment in prison; in response, authorities subjected them to forced feeding. Faced with terrible publicity, officials finally released all picketers in late November. That fall, both houses of Congress began to move toward voting on a federal amendment. By this time, all suffragists were focused intently on the federal amendment, but the NWP activists made it clear that they were not going to stop until they got it or died trying. 37

Women’s contributions to national war efforts did affect public opinion, but female enfranchisement did not follow immediately or easily. In January 1918 , President Wilson endorsed suffrage the day before the House of Representatives would vote again on the federal amendment, but the outcome was highly uncertain. Great efforts were made to guarantee every positive vote: several ailing representatives dragged themselves or were carried in, while another left his wife’s deathbed (at her urging), then returned for her funeral. Three roll calls were necessary to establish that the measure had passed with exactly the required two-thirds majority, supported by a significant number of western congressmen responding to pressure from enfranchised female constituents.

The Final Struggle for the Federal Amendment

Hopes for a quick victory were soon shattered. Wilson was preoccupied with the war, so an impatient NWP resumed militant demonstrations that generated more arrests, jail sentences, and publicity. It took a year and a half for the Senate to vote, and only at the instigation of hostile senators confident that it would lose. On September 30, Wilson took the unusual step of addressing the Senate during the debate, describing enfranchisement as only fair considering all the contributions women had made to the war effort, but states’-rights advocates remained adamantly opposed, and it lost by two votes. By December, even the NAWSA threatened to mobilize against unsympathetic politicians in the 1918 elections, and both suffrage organizations did so. In February 1919 , the Senate defeated the amendment again—by one vote—but six more state legislatures had granted women the vote by the time Wilson called Congress into special session in May. This time the measure carried in the House by a wide majority (thanks to the election of over one hundred new pro-suffrage legislators) and passed the Senate on June 4 by a two-vote majority. 38

Ratification of the amendment required another long struggle. It came quickly in states where suffrage organizations remained active, but the process dragged on into 1920 . Finally only one more state was needed, but most of the holdouts were in the South. The battle came to a head in August in Tennessee, with relentless lobbying by pro- and anti-suffrage forces and reports of threats, bribes, and drunken legislators. The state senate passed the measure easily, but in the house there were numerous delays engineered by the opposition, and suffragists believed that they lacked the last votes needed for passage. When the roll call reached Harry Burn, a young Republican from the eastern mountains, he unexpectedly voted “aye,” later explaining that his mother had written urging him to support the measure.

7. Alice Paul and NWP members in August 1920 celebrating passage of the Nineteenth Amendment with a toast to the final 36 th star on the woman suffrage flag.

Thus the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution squeaked to victory. 39

Gaining the right to vote was a huge accomplishment, but it did not automatically guarantee women other political rights (e.g., running for office or serving on juries), nor did it rectify many other discriminatory practices embedded in the law. To address these issues, the NWP introduced the federal Equal Rights Amendment in 1923 , but nearly a century later, it remains unratified. To prepare women for their new civic responsibilities, in 1920 Catt converted the NAWSA into the League of Women Voters (LWV), an organization still dedicated to nonpartisan educational activity. Until recently, analyses of the impact of female enfranchisement focused on the national level during the conservative decade of the 1920s and found little to report: women did not form a solid voting bloc, so major parties soon lost interest in cultivating their support, and few women were elected to office. More recent research suggests a more complicated dynamic, especially at the state level. Although technically enfranchised, spurious restrictions and violence prevented African American women and men from voting for decades, especially in the South. Thus winning the vote did not guarantee all American women full equality, but it recognized their fundamental right of self-representation, permanently changed the composition of the polity, and provided the necessary foundation for subsequent achievements.

Discussion of the Literature

There has been relatively little scholarly interest in the U.S. suffrage movement in recent years. Since this topic was the primary focus of attention as the field of women’s history began to develop, perhaps people think it has been thoroughly examined. That assumption is incorrect for at least two reasons. First, more recent research has identified and investigated previously unexplored aspects, resulting in many new insights, while other topics still deserve fuller attention. Second, we still lack an up-to-date synthetic account that incorporates the findings of these studies, although several excellent essay collections are available. Scholars continue to rely upon the monumental work, The History of Woman Suffrage , compiled by NAWSA activists conscious of the need to document their historic struggle, but it is best treated with caution as a collection of primary sources. In 1959 , Eleanor Flexner published a now-classic synthesis, Century of Struggle (enlarged by Ellen Fitzpatrick and reprinted in 1996 ). This book remains the standard account, but it includes discussions of various contributing factors that have since been well studied as separate topics (e.g., women’s access to education and wage work). No one since has taken on the daunting task of producing a comprehensive account of this vitally important movement.

With surprisingly few modifications, the narrative of the U.S. suffrage struggle has remained static: the Seneca Falls convention was the moment the movement began; it split over controversies precipitated by the Reconstruction Amendments, western victories were anomalous, and the “doldrums” of the 20th century were followed by reinvigoration in the 1910s, culminating in the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. The many summary essays available online and books for young people may or may not integrate recent findings, but they all repeat this dominant narrative, so it is past time for a new synthesis that amends, refines, and expands our understanding of this long, complicated, and difficult struggle.

Heavily influenced by the publication of Aileen Kraditor’s book, The Ideas of the Woman’s Suffrage Movement ( 1965 ), subsequent studies thoroughly disrupted any lingering notions about a coherent suffrage “sisterhood.” Kraditor argued that late 19th-century suffragists stopped emphasizing the “justice” of their cause in favor of “expediency” arguments focused on how the vote could be used to achieve other goals. This argument set up a false dichotomy since suffrage arguments based on rights and justice continued to be frequently and powerfully employed, while the exercise of the vote has always been a commonly accepted means to achieve political objectives. Yet there is no doubt that Kraditor’s work made a huge contribution by revealing a movement deeply affected by the elitism, racism, and nativism of many suffragists. It stimulated extensive investigation into problematic tensions among different groups of suffragists as well as analyses of the negative impacts on their audiences.