An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Malpractice Liability and Health Care Quality

Michelle m mello , jd, phd, michael d frakes , jd, phd, erik blumenkranz , jd/mba cand., david m studdert , llb, scd.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author: Dr. Mello, Stanford Law School, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, CA 94305; (650) 924-5382; [email protected]

The tort liability system is intended to serve three functions: compensate patients who sustain injury from negligence, provide corrective justice, and deter negligence. Deterrence, in theory, occurs because clinicians know that they may experience adverse consequences if they negligently injure patients.

To review empirical findings regarding the association between malpractice liability risk (i.e., the extent to which clinicians face the threat of being sued and having to pay damages) and healthcare quality and safety.

Data sources and study selection

Systematic search of multiple databases for studies published between January 1, 1990 and November 25, 2019 examining the relationship between malpractice liability risk measures and health outcomes or structural and process indicators of healthcare quality.

Data extraction and synthesis

Information on the exposure and outcome measures, results, and acknowledged limitations was extracted by 2 reviewers. Meta-analytic pooling was not possible due to variations in study designs; therefore, studies were summarized descriptively and assessed qualitatively.

Main outcomes and measures

Associations between malpractice risk measures and healthcare quality and safety outcomes. Exposure measures included physicians’ malpractice insurance premiums, state tort reforms, frequency of paid claims, average claim payment, physicians’ claims history, total malpractice payments, jury awards, the presence of an immunity from malpractice liability, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Medicare Malpractice Geographic Practice Cost Index, and composite measures combining these measures. Outcome measures included patient mortality; hospital readmissions, avoidable admissions, and prolonged length of stay; receipt of cancer screening; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators and other measures of adverse events; measures of hospital and nursing home quality; and patient satisfaction.

Thirty-seven studies were included; 28 examined hospital care only and 16 focused on obstetrical care. Among obstetrical care studies, 9 found no significant association between liability risk and outcomes (such as Apgar score and birth injuries) and 7 found limited evidence for an association. Among 20 studies of patient mortality in non-obstetrical care settings, 15 found no evidence of an association with liability risk and 5 found limited evidence. Among 7 studies that examined hospital readmissions and avoidable initial hospitalizations, none found evidence of an association between liability risk and outcomes. Among 12 studies of other measures (e.g., Patient Safety Indicators, process-of-care quality measures, patient satisfaction), 7 found no association between liability risk and these outcomes and 5 identified significant associations in some analyses.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this systematic review, most studies found no association between measures of malpractice liability risk and healthcare quality and outcomes. Although gaps in the evidence remain, the available findings suggested that greater tort liability, at least in its current form, was not associated with improved quality of care.

Keywords: malpractice, liability, tort, deterrence, safety, quality

The medical liability system is intended to serve three functions: compensate patients injured by negligence, promote corrective justice by providing a mechanism to rectify wrongful losses caused by defendants, and deter negligence. 1 Deterrence is the notion that liability can make healthcare safer. Theoretically, clinicians will respond to the threat of being held liable for malpractice. Because evidence suggests that the tort system performs poorly as a means of providing patients with compensation for injuries related to negligence 2 and rarely provides meaningful corrective justice, 2 , 3 a belief in deterrence motivates many defenders of the tort system. 4

Whereas deterrence leads clinicians to calibrate safety responses so that the costs do not exceed the benefits, a related phenomenon, defensive medicine, reflects responses that are costly and provide little or no clinical benefit. Evidence of defensive medicine is common, 5 whereas evidence of deterrence is more elusive. The standard approach in deterrence studies is to compare levels of healthcare quality across environments with relatively high and low liability risk. This approach cannot evaluate what healthcare quality would be like in the absence of liability risk, but can reveal whether the extent of liability risk is related to health care outcomes.

Does malpractice liability risk—that is, the extent to which clinicians face the threat of being sued and having to pay damages—contribute to improvements in the quality and safety of healthcare? The question is relevant to assessing the role of the liability system in the patient safety movement. Because malpractice litigation might inhibit error disclosure, clinicians may view tort litigation as counterproductive to quality improvement; 6 yet, legal practitioners view injury prevention as one of the fundamental functions of tort law. The question matters for tort reform efforts, as skepticism about the deterrent effect of malpractice litigation reinforces arguments that liability can be limited without risking the quality of care.

The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the association between malpractice liability risk and healthcare quality and safety, and thereby assess the evidence for deterrence as it relates to clinicians.

Search Strategy and Study Eligibility

We performed a systematic review in July 2018 of articles published or otherwise made public from January 1, 1990 to July 10, 2018; results were subsequently updated with an additional search through November 25, 2019. The search protocol was registered on PROSPERO ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ , number CRD42018103723) and is provided in sections S1 and S2 of the Supplemental Appendix . We searched 5 databases (Web of Science, MEDLINE/PubMed, Westlaw, EconLit, and SSRN) using combinations of keywords related to liability risk (e.g., malpractice, liability, tort, deter, negligence, defensive, litigation) and measures of health-related outcomes (e.g., outcome, quality, safety, care, deter, patient) (exact strings for each database provided in Supplemental Appendix section S3 ). For example, the search string used for Web of Science was “TI=(malpractice OR liab* OR tort OR deter OR deterren* OR negligen* OR defensive OR litigation) AND TS=(physician OR doctor OR hospital OR clinic OR provider OR practitioner) AND TS=(quality OR safety OR deter* OR outcome OR care OR patient) AND CU=(USA)”. We also examined the bibliographies of relevant articles for citations to additional papers, and included relevant working papers known to us through conference presentations and personal contacts with colleagues; together these methods added 5 studies to the sample.

After eliminating duplicate articles, we reviewed the articles retrieved and applied prespecified inclusion criteria. These criteria identified original empirical studies of the association between indicators of malpractice liability risk and indicators of healthcare quality and safety that used study approaches (e.g., multivariable regression analysis) designed to address potential sources of confounding. To identify healthcare quality measures, we used the Donabedian framework 7 and included measures of structure, process, and outcomes that unambiguously reflect good or poor quality care. Thus, services such as prenatal care and receiving beta blockers after myocardial infarction met our criteria (process), as did nurse staffing ratios (structure). Studies that examined the relationship between liability risk and measures that are more reflective of costs than quality were not included. For these reasons, studies focusing on caesarean deliveries and most types of diagnostic tests were excluded. Such services are considered overutilized, due in part to defensive medicine. Unless studies accounted for clinical circumstances that distinguished appropriate from inappropriate use (for example, separating elderly from young patients in examining screening mammography 8 ), they were deemed unhelpful in assessing deterrence. If a study examined multiple outcome measures, we included only analyses of outcomes that met our criteria.

Each study was reviewed for potential inclusion by 1 reviewer. When review of the title and abstract alone was insufficient to reach a decision about the eligibility of the study for inclusion, the full text was reviewed. If the reviewer remained uncertain as to whether a study met inclusion criteria, all 3 reviewers reviewed the full text of the study and resolved the issue through discussion.

To update the search results prior to publication of this review, supplemental searches using the same protocol with date range July 2018 to November 25, 2019 were performed.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

For each eligible study, we extracted into an Excel spreadsheet information on the authors, year published or released, exposure measures, outcome measures, data sources, sample size, level of analysis (patient, facility, physician, or geographic unit), results (direction and magnitude of association with malpractice risk variables), authors’ conclusions, and acknowledged limitations. The reported findings were considered to be in the direction of deterrence if greater liability risk was associated with better outcomes, whereas reported findings were considered to be in an anti-deterrence or reverse deterrence direction if greater liability risk was associated with worse outcomes. Study type is not reported because all but one study (a case-control analysis of emergency physicians) 9 took the same basic approach of using multivariable regression analysis to examine a retrospective sample of one or more years of data.

Meta-analytic pooling was not possible due to variations in study features, especially the large number of different exposures and outcome measures modeled. Consequently, studies were summarized descriptively. We characterized as statistically significant those associations reported in the sampled studies that achieved the 0.05 significance level, except that we used significance levels corrected for multiple comparisons for studies that reported them. To avoid replicating possible bias in study authors’ selective emphasis of particular study results, we examined tables of regression results rather than relying on summaries from the study authors.

Quality Assessment

Because of the nature of the study designs, it was not possible to use existing instruments to assess the risk of bias in research. Existing tools for assessing observational studies (for example, Newcastle-Ottawa and ROBINS-I) were designed for clinical and epidemiologic studies, and no comparable tool is used in the field of econometrics. For that reason, we performed an independent, qualitative risk-of-bias assessment, summarizing the strengths and weaknesses of the study. To ensure rigor, each article was reviewed by 2 team members with training in econometrics who were not involved in the study being evaluated. In addition to extracting limitations acknowledged by the study authors, reviewers noted strengths and weaknesses pertaining to the data source (e.g., sample size, population covered, range of covariates incorporated, usefulness of measures, whether the data could support individual-level models), model estimation methods (e.g., identification strategy, control for confounders, potential endogeneity, robustness checks), and any concerns about the accuracy of the study authors’ characterizations of the study findings.

Study Characteristics

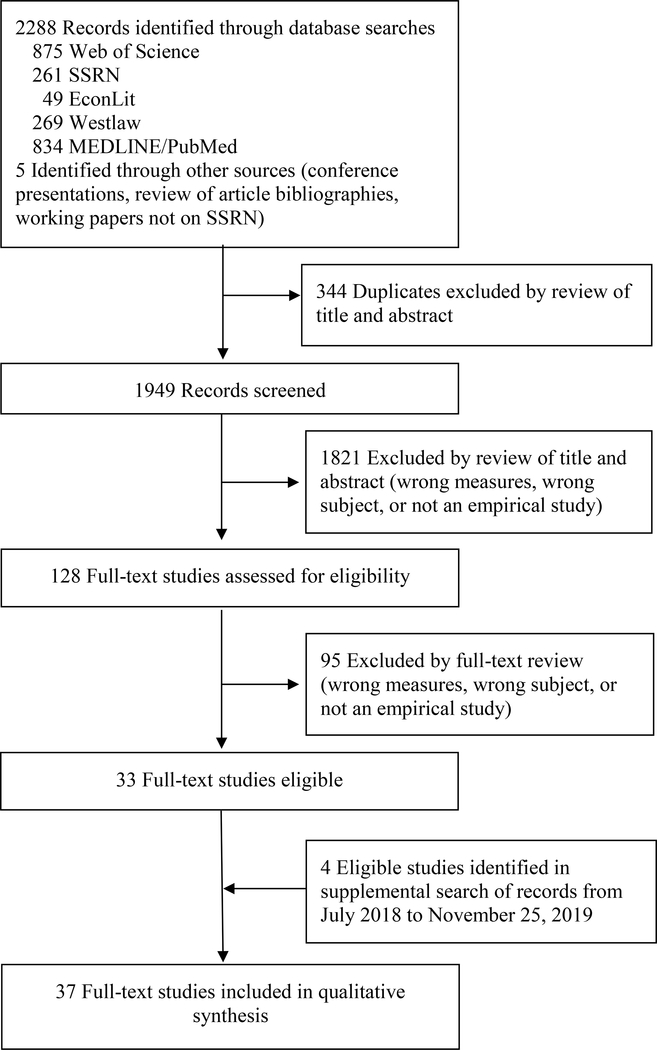

The original search identified 1949 unique studies as potentially eligible for inclusion; 1821 of these were screened out after review of the article title and abstract and another 128 were deemed ineligible after review of the full text ( Figure 1 ; details in Supplemental Appendix section S3 ). Thirty-three studies met our inclusion criteria, 4 of which were unpublished. The supplemental update search added 4 eligible studies. Selected characteristics of the final sample of 37 studies are presented in Table 1 and additional details are in Supplemental Appendix eTable 2 .

Study Identification and Selection

Selected Characteristics of the 37 Studies Included in the Qualitative Synthesis a

Abbreviations: MI, myocardial infarction; IHD, ischemic heart disease; PSI, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicator; RN, registered nurse; ADL, activities of daily living; UTI, urinary tract infection; CHD, coronary heart disease; VTE, venous thromboembolism; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; HCAHPS, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems.

Studies are ordered chronologically. All studies are multivariable regression analyses on one or more years of retrospective data. Full information abstracted from each study is provided in the Appendix .

Only those outcome measures meeting study inclusion criteria are presented in the Table.

Studies varied in how sample sizes were reported, with some studies reporting model-specific sample sizes and others only the overall sample size, or none at all.

Immunity arises from the Feres doctrine, which precludes liability for malpractice in medical encounters with active-duty servicemembers.

All studies used multivariable regression analysis to assess the association between the exposure and outcome variables in a longitudinal or cross-sectional sample. Because studies varied in their unit of analysis, from patient or physician to county, region, or state, the number of observations per study ranged from 50 to more than 132 million ( Table 1 ). For example, Dhankhar and Khan 10 analyzed 100 state-year observations and Yang et al. 11 analyzed 2,354,561 births.

Exposure Measures

The studies measured the extent of malpractice liability risk in a given environment in several ways ( Table 1 ). Physicians’ malpractice insurance premiums and the presence of liability-limiting tort reforms in the state were the most common exposure measures (n=21 studies). Other measures included the frequency of paid claims in the state or county (n=13), insurance premiums (n=7), average payment per paid claim (n=8), physicians’ claims history (n=5), total malpractice payments in the state or county (n=2), jury awards in the county (n=1), immunity from malpractice liability (n=1), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Medicare Malpractice Geographic Practice Cost Index (MGPCI) (a measure of premium costs to physicians in local liability insurance markets) (n=1), and composite measures incorporating more than one of the foregoing (n=3). Data sources for exposure measures included the National Practitioner Data Bank (a national repository of information on paid malpractice claims), insurance industry rate surveys, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, jury awards databases, and 50-state summaries of state legal reforms.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures included patient mortality; hospital readmissions, avoidable admissions, and prolonged length of stay; receipt of cancer screening services; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs) and other measures of adverse events and postoperative complications; measures of hospital and nursing home quality; and patient satisfaction (see Table 1 for measures used in each study). Three quarters of the studies (28/37) focused on hospital care only, and nearly half (16/37) focused on obstetrical care. Studies outside the obstetrics context commonly measured associations between liability risk and patient mortality, although more recent studies examined associations with PSIs. Data sources for outcome measures included Medicare and other claims data, vital statistics records, physician practice group databases, cancer registries, and surveys.

Evidence Relating to Obstetrical Care

Of the 16 studies examining obstetrical care, 9 identified no significant associations between liability risk and quality in the direction of deterrence ( Table 2 ). Seven studies found limited evidence of associations, i.e., the statistical significance, direction, or both of the associations were sensitive to the model specification used, the patient group studied, or the outcome measure examined.

Studies Examining Associations Between Malpractice Liability Risk Measures and Obstetrical Care, 1990–2019 (n=16) a

PSI = Patient Safety Indicator; JSL = joint-and-several liability rule reform; CSR = collateral-source offset rule reform

Measures are listed in abbreviated form; see Table 1 for details.

“No” evidence of deterrence indicates that no model found statistically significant associations between the liability measure and any outcome measure, or that the only statistically significant associations were in an anti-deterrence direction (i.e., greater liability risk was associated with worse rather than better outcomes). For detailed quantitative results, see Supplemental Appendix Table S2 .

Several studies found no significant association between liability measures and outcomes in the direction of deterrence. Entman et al 12 found that obstetricians’ personal history of malpractice claims was not associated with quality of care or frequency of adverse events. Three studies using malpractice premiums as the exposure measure found no associations with Apgar scores, low birthweight, preterm birth, or birth injury. 11 , 13 , 14 In a study of military physicians, who are immune from malpractice litigation related to their care of active-duty servicemembers (but not other patients), Frakes and Gruber 15 found no association between immunity and several adverse birth outcomes (preventable delivery complications, neonatal mortality, neonatal trauma, and maternal trauma in vaginal deliveries). Two studies by Dubay et al 13 , 14 found that tort reforms were not associated with prenatal health care utilization, low birthweight, or Apgar scores. Frakes 16 also found no association between tort reforms and Apgar scores. Frakes and Jena 17 did not find tort reforms to be associated with any of several obstetrical PSIs. Kim 18 found neither claim frequency nor average claims payments were associated with prenatal care utilization or use of cesarean delivery in patients with breech presentation. Malak and Yang 19 found no association between tort reforms and infant mortality or preventable birth complications.

Several studies identified limited evidence of an association between liability measures and outcomes in the deterrence direction. Sloan et al 20 found a significant association between liability risk and birth outcomes in the direction of deterrence in 2 of 23 models tested. In county-level analyses using survey data, both claim frequency and total claims payments were associated with reduced risk of fetal mortality. However, these associations did not achieve statistical significance in physician-level models, and neither liability measure showed significant associations with any of the other 4 outcome variables (low Apgar score, 5-day neonatal mortality, infant mortality, or death or permanent impairment at age 5) in any model. In analyses using a larger sample of county birth records, no associations between liability risk measures and birth outcomes were significant at the p<0.05 level.

A subsequent study by Sloan et al 21 found claim frequency to be significantly associated with prenatal care utilization in the direction of deterrence in 1 of 8 models tested. In physician-level models, claim frequency was significantly associated with greater use of alpha-feto protein tests, but not with greater use of ultrasound or diabetes tests. The relationship between claim frequency and use of amniocentesis was significant in the direction opposite of deterrence (i.e., claim frequency was associated with less use of amniocentesis). In county-level models, no significant associations were observed between claim frequency and any of 4 measures of patient satisfaction (doctor is interested in your and your baby, doctor fully explained the reason for each test and procedure, doctor ignored what you told him/her, and you felt you could call doctor with questions).

Dhankhar and Khan 10 also examined claim frequency, along with mean payment amounts per paid claim. Among 56 models (in which patients with Medicaid coverage and those with private insurance, and births involving necessary and unnecessary cesarean sections, were analyzed separately), 53 models found no significant associations with the 7 birth outcomes examined. Two models found a significantly lower risk of neonatal respiratory distress among patients with private insurance and unnecessary c-sections. One model found a reverse deterrence association (i.e., increased claim frequency was associated with an increased risk of neonatal respiratory distress) for Medicaid patients with necessary c-sections.

Three studies that examined tort reforms also found no evidence of an association between liability risk and health outcomes in the direction of deterrence in most models. Klick and Stratmann 22 studied 7 tort reforms in relation to mortality among black and white infants (modeled separately) and found no significant deterrence associations in 25 of 28 models. Only collateral-source rule reform (which consists of deducting from plaintiffs’ malpractice awards amounts already reimbursed by insurance and other sources) was consistently associated with mortality across model specifications in the direction of deterrence (i.e., tort reform was associated with increased infant mortality), although this association was observed only among black infants. Joint-and-several liability reform (which consists, in cases involving multiple defendants, of limiting the damages each must pay to an amount proportional to that defendant’s percentage fault for the injury) was associated with increased mortality for white infants in 1 of 2 model specifications, but was not significant in either model specification for black infants. Two models produced reverse deterrence findings, i.e., greater liability was associated with worse outcomes. Currie and Macleod studied 4 tort reforms in relation to preventable birth complications and low Apgar scores, and found that noneconomic damages caps were associated with an increase in the preventable complication rate but were not associated with Apgar score. Joint-and-several liability reform was associated with a decrease in preventable complications, which is a reverse deterrence finding because that reform limits defendants’ liability. There was no significant association between joint-and-several liability reform and low Apgar score, or between the other tort reforms examined (punitive damages caps and collateral-source rule reform) and either of the outcomes. Iizuka 23 examined 4 tort reforms and 4 birth-related PSIs, modeling them at both the hospital and patient levels, and found that only collateral-source rule reform was significant in a direction consistent with deterrence, and only in hospital-level models that examined injuries to neonates (2.36 more injuries per hospital-year when collateral-source rule reform was implemented to reduce liability, p<0.01) and mothers (5.7 more injuries per hospital-year, p<0.05); neither of those associations was significant in the patient-level models.

In an analysis that examined the relationship between noneconomic damages caps and 3 PSIs plus a pooled PSI, Zabinski and Black 24 found more consistent associations in the direction of deterrence across model specifications, but only for maternal outcomes. In a model examining all states, the coefficient was significant and positive (i.e., in the direction of deterrence) for the pooled measure and 1 PSI (representing a 7% increase in the rate of maternal trauma in vaginal deliveries when noneconomic damages were capped), but not for the other 2 PSIs (neonatal injury and maternal trauma in deliveries without instruments). In single-state models, the association between noneconomic damages caps and outcomes was significant for the pooled measure and 1 PSI in 4 of 5 states, significant in 1 state for 1 PSI, and significant in 2 states for the other PSI.

Overall, studies found very limited or no evidence of associations between liability risk and outcomes in obstetrical care that indicate deterrence. The variations in findings were not clearly correlated with the choice of either the exposure measure or the outcome measure, although only 1 of the 6 studies that examined mortality as an outcome found any evidence of an association.

Evidence Concerning Patient Mortality

Twenty studies examined the relationship between liability risk and patient mortality (in settings other than obstetrical care) and 15 found no statistically significant associations in the direction of deterrence ( Table 3 ). Three studies reached different conclusions about deterrence depending on the liability measure modeled and states investigated, 24 – 26 and 2 studies yielded less equivocal evidence of deterrence. 27 , 28

Studies Examining Associations Between Malpractice Liability Risk Measures and Patient Mortality in Non-Obstetrical Contexts, 1990–2019 (n=20) a

MI = myocardial infarction; IHD = ischemic heart disease; CHD = coronary heart disease; CMS = Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

Of the 15 studies that reported no significant associations between liability measures and mortality in the deterrence direction, 9 used tort reforms as the measure of liability risk and 6 used claim frequency, average payment per paid claim, jury awards, or other measures ( Table 3 ). These studies were also diverse in the patient populations studied, ranging from narrowly defined disease groups (e.g., patients with bladder cancer, 29 patients undergoing cranial neurosurgery 30 ) to wide patient populations (e.g., all Medicare patients 31 , 32 ).

Two of the 3 studies that found limited evidence of deterrence used tort reforms as the measure of liability risk. Zabinski and Black 24 focused on noneconomic damages caps and found no significant deterrence relationships in 14 of 18 models tested, including all models that pooled data from more than one state. In 2 of 5 single-state models, damages caps were significantly associated with higher mortality for 2 of the 3 mortality measures (one individual PSI and a measure pooling 2 death PSIs). Shepherd 26 modeled 6 tort reforms and found that 2 (total damages caps and collateral-source rule reform) were significantly associated with state-level, non-motor-vehicle-related deaths in the direction of deterrence (i.e., deaths increased when liability was limited), whereas 2 (noneconomic damages caps and punitive damages reform) were significantly associated with mortality in a reverse-deterrence direction (deaths decreased when liability was limited), and 2 (periodic payment and joint-and-several liability reform) had nonsignificant results. A study by Dhankhar et al 25 that used claim frequency and average payments per paid claim as the liability risk measures found that an increase in the number of paid claims by one case per 100,000 population was associated with a statistically significant, 13% lower risk of in-hospital mortality among patients with myocardial infarction, but found no association between mean payment amounts and mortality.

Two studies found more consistent evidence of an association between liability risk and outcomes in the direction of deterrence. Lakdawalla and Seabury 27 estimated that a doubling of a county’s jury award dollars per capita in malpractice cases was associated with a 2% decrease in the county’s all-cause mortality rate; this is a surprisingly large effect size considering that only a small fraction of deaths were due to medical injury. Bilimoria et al 28 examined 3 measures of liability risk in a model of 30-day mortality for hospitalized patients with myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The authors found that claim frequency was not significantly associated with mortality, although higher Medicare Malpractice Geographic Practice Cost Index was significantly associated with lower mortality for all 3 conditions, and a composite liability measure was significantly associated with lower mortality for patients with heart failure. However, most studies found no evidence of an association between higher liability risk and lower patient mortality.

Evidence Relating to Avoidable Hospitalizations and Readmissions

Six studies examined the relationship between liability risk and hospital readmissions and a seventh examined associations with avoidable hospitalizations ( Table 4 ). All 6 studies found no significant association between liability risk and readmissions, despite testing diverse liability measures and patient populations ranging from narrow (e.g., patients undergoing colorectal surgery 33 ) to broad (e.g., patients seeing military physicians 15 ). In an analysis of avoidable hospitalizations, Frakes and Jena 17 found no significant association between 4 tort reforms (noneconomic damages caps, punitive damages caps, collateral-source rule reform, and joint-and-several liability reform) and hospital readmissions. 17

Studies Examining Associations Between Malpractice Liability Risk Measures and Readmissions and Avoidable Hospitalizations, 1990–2019 (n=7) a

MI = myocardial infarction; IHD = ischemic heart disease; CMS = Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

Evidence Concerning PSIs and Postoperative Complications

Six studies examined the association between liability risk and rates of PSIs or other measures of postoperative complications outside the obstetrical care context ( Table 5 ). Of these, 4 studies found no evidence of deterrence, 15 , 30 , 33 , 34 1 found evidence in only a small number of the many models included in the study, 28 and 1 found evidence in the majority of models tested. 24

Studies Examining Associations Between Malpractice Liability Risk Measures and Other Outcomes, 1990–2019 (n=12) a

PSI = patient safety indicator; CMS = Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; HCAHPS = Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems.

The variation in results across studies is not clearly attributable to the choice of exposure or outcome measures. 28 However, although the 4 studies that found no significant association between liability risk measures and health outcomes included a wide range of liability measures (claim frequency, average payments, premiums, legal immunity, and composite measures), none used tort reforms as the exposure measure. The study that reported limited evidence of deterrence, Bilimoria et al, 28 included tort reforms as an exposure measure and concluded there was no “consistent pattern of association” with 5 PSIs across the reforms (quantitative results were not reported). The same study found, in 15 other models testing the association of 3 other types of liability measures with each of the 5 PSIs, that findings were significant in the deterrence direction in 2 models (MGPCI and iatrogenic pneumothorax; and MGPCI and unintentional punctures/lacerations). Two models had significant results in the reverse deterrence direction, and 11 other models found no significant association between liability measures and outcomes.

A study by Zabinski and Black, 24 which tested noneconomic damages caps only, was an outlier in terms of findings, and identified evidence of deterrence in most (62/93) models tested. For example, in models that pooled multiple PSIs and all states, the authors found that caps were associated with a 0.16 percentage point increase in the incidence of any PSI (p<0.05) and a 0.04 percentage point increase in the incidence of operating room PSIs (p<0.05). The findings concerning deterrence were relatively consistent across pooled models, but were mixed for models of individual PSIs and single states.

Overall, most studies found that higher liability risk was not associated with improved performance on PSIs or decrease rates of postoperative complications.

Evidence Relating to Other Quality Measures

Two studies investigated the relationship between liability risk and rates of clinically appropriate cancer screening ( Table 5 ). Baicker and Chandra 8 identified significant associations between liability risk and mammography rates in models using mean malpractice claim payments as the exposure measure, but no significant associations in models using claim frequency or insurance premiums. Frakes and Jena 17 found no relationship between tort reforms and cancer screening rates.

Three studies examined process-of-care measures of quality ( Table 5 ). The study by Bilimoria et al 28 of 17 Hospital Compare measures found no significant associations in the direction of deterrence between the state malpractice environment and process-of-care quality measures. Stevenson et al 35 examined the relationship between a nursing home’s claims experience and 9 process and outcome measures of quality and also found no significant deterrence relationships. In analyses of nursing home quality, Konetzka et al 36 found a significant association in a deterrence direction in 1 of 3 models. Claim frequency was significantly associated with a more favorable ratio of registered nurse to total staffing hours, although the effect size was small (2.4% increase in the ratio for a 1-standard-deviation increase in claim frequency).

Two studies found no significant association between liability risk and patient satisfaction, although a third study found evidence of deterrence ( Table 5 ). Sloan et al 21 found no relationship between claim frequency and obstetrical patients’ satisfaction ratings, and Bilimoria et al 28 found that MGPCI, claim frequency, tort reforms, and a composite measure were not associated with Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems ratings. However, Carlson et al 9 found that emergency physicians who experienced a claim had significantly higher patient experience scores after the claim was filed (increase of 6.52 in Press Ganey percentile rank, 95% CI 0.67–12.38).

Qualitative Risk-of-Bias Assessment

Study-specific assessments of risk of bias are provided in Supplemental Appendix eTable 2 . Although the quality of these articles could not be assessed using standard quality assessment tools, the methodological assessment we conducted revealed that, with few exceptions, 10 , 25 , 26 most studies included in this review used appropriate analytical methods, including good controls for confounding and exploration of the robustness of results to changes in model specification. The varied study results were not evidently attributable to the choice of measures, analytic approaches, or sample sizes. Although all of the studies in this review have limitations, none can be dismissed as methodologically unsound. The study that had outlier findings, Zabinski and Black, 24 did not have obvious weaknesses other than its narrow focus on noneconomic damages caps.

However, the quality assessment identified several methodological limitations that may affect the ability of some studies to accurately measure the extent and nature of associations between the exposure and outcome measures. First, a general limitation of the evidence base examined is that all studies but one 15 examined that extent of change in the outcome measures when liability risk was higher versus lower, rather than the absolute effect associated with tort liability risk. Second, although studies that examined what happened during hospitalization may find no evidence of deterrence, it is possible that liability risk affects inpatient mix. In areas with high liability risk, physicians who are concerned about liability might be more inclined to admit to the hospital patients whose need for hospitalization is less clear (i.e., these patients may be healthier than other admitted patients on average). After tort reform is passed, there may be lower tendency to admit such patients, in which case the average admitted patient would have higher severity of illness and be more prone to poor outcomes. The most likely consequence of such selection effects would be spurious positive findings of deterrence; they are less likely to invalidate null findings.

Third, in some studies that used tort reforms as the exposure measure, only a few states adopted reforms during the study period. For example, in the study by Zabinski and Black 24 only 5 states changed their noneconomic damages caps laws in the years studied. In such circumstances, regression estimates may have low precision and be subject to confounding by unobserved, time-varying effects. 37

Fourth, some analyses may have unexplored problems of two-way causation. For instance, adverse events are an established risk factor for malpractice claims. 36 , 38 , 39 A regression model that evaluates the relationship between adverse event rates and claim frequency without accounting for this cannot support the kind of causal inference a firm conclusion about deterrence requires.

Fifth, some studies relied on state- or county-level outcomes data. For instance, Klick and Stratmann 22 used state infant mortality rates, Baicker and Chandra 8 used state-level mammography rates for Medicare patients, Shepherd 26 used state mortality rates for non-motor-vehicle accidents, and Lakdawalla and Seabury 27 used county all-cause mortality rates. Drawing causal inferences with such measures can be problematic because group aggregation reduces information and may mask important differences between individuals in the group. 40

Sixth, aggregation was also common in construction of exposure variables. Most studies measured liability risk indicators at the state or county level, rather than the level of the individual physician, and no studies measured physicians’ perceived levels of liability risk. Physicians may have different awareness of and reactions to such environmental indicators, making physician-level analyses preferable. More studies should examine whether particular physicians change their clinical behavior after they have been sued and, ideally, parse sued physicians according to the subjective intensity of their liability experience.

Seventh, some studies were narrow in focus. Kessler and McClellan 41 , 42 examined only patients hospitalized with 2 cardiac conditions; Konety et al 29 focused solely on patients with bladder cancer; Avraham and Schanzenbach 43 only studied deaths due to coronary heart disease; Missios and Bekelis 44 only included patients who had spine surgery; Bekelis et al 30 focused on patients who had undergone cranial neurosurgery; and Bilimoria et al 33 only included patient who had colorectal surgery. Findings from these distinct analyses may or may not replicable in broader samples.

This review of 37 studies of malpractice deterrence conducted since 1990 found that most studies suggest that higher risk of malpractice liability is not significantly associated with improved healthcare quality. Studies that examined obstetrical care were most likely to have identified some significant associations, but even in that domain there was inconsistency across analyses, including analyses within the same study, and most analyses did not identify evidence of deterrence. Notwithstanding some methodological shortcomings, collectively this body of evidence is sufficient to support a conclusion that higher tort liability risk was not systematically associated with safer or higher-quality care in the hospital setting. Because only a limited number of studies addressed care delivered in other settings, it is not possible to draw conclusions about deterrence in those clinical contexts.

In theory, the deterrence effect of malpractice liability risk could proceed through three mechanisms. The first is economic: malpractice claim payments impose a direct financial sanction. Most physicians are well insured for malpractice 45 and awards rarely exceed coverage limits, 46 but physicians may experience economic effects if their insurance premiums increase or their medicolegal track record adversely affects their clinical income. 47 Healthcare facilities may be affected by economic sanctions more readily than physicians because their insurance generally involves greater experience rating, meaning that premiums are determined in part based on how costly the facility’s claims were in a prior period. The second mechanism (which is less applicable to healthcare facilities) is that the psychological stress and trauma of litigation can be severe, and physicians will endeavor to avoid experiencing them. 48 , 49 The third mechanism is informational. Not all malpractice claims are meritorious, but some convey information about deviations from standards of care. Individual clinicians, healthcare facilities, health insurers, and regulators may then respond to those signals in ways that may prevent harm.

Our systematic review suggests that notwithstanding these theoretical mechanisms, malpractice liability risk may not be effective in preventing substandard care. One possible explanation relates to the etiology of medical error. Some errors involve momentary or inadvertent lapses at the individual clinician level. 50 , 51 Although hospitals might be able to implement systems to identify some such errors before they cause harm, other errors are not amenable to the kind of conscious precaution taking (at either the hospital or the physician level) on which the deterrence model relies.

Previous reports have identified 3 other problems, which have continuing relevance. 45 The first (and perhaps largest problem) is that most instances of medical negligence that cause harm never become malpractice claims, whereas many claims of uncertain or no merit are filed. The poor fit between claims and negligence introduces noise into the deterrent signal, reinforcing physicians’ perceptions that claims do not convey valid information about their quality of care.

Insurance is a second contributing factor. Unlike causing a motor vehicle crash, causing a malpractice injury does not ordinarily result in higher insurance premiums for the involved individual. It is actuarially difficult for insurers to apply experience rating at the physician level, so paid claims do not tend to manifest as direct economic sanctions for the physician. This is less of a problem at the facility level, where self-insurance and experience rating are common.

A third issue is uncertainty about the legal standard of care. Physicians complain that they do not know what “negligence” is—i.e., precisely what the law requires in a given clinical situation. Such uncertainty may contribute to undercutting the desired behavioral change.

Policy levers exist that could address these problems. For example, adopting enterprise liability, a reform that shifts the primary locus of liability from individual practitioners to larger organizations such as hospitals or accountable care organizations, would be helpful. 45 Organizations experience the economic aspect of deterrence more strongly than physicians because they are sued more often and have experience-rated insurance. 45 Organizations are also better positioned to effectuate changes in care that transcend individual practitioners. Another pertinent lever would be widespread implementation of communication-and-resolution programs (CRPs), through which healthcare facilities disclose adverse events to patients, rapidly investigate them, and offer proactive compensation when deviations from the standard of care have caused harm. 52 These programs could result in a higher proportion of negligent events receiving compensation, thereby reinforcing the economic and psychological mechanisms of deterrence. Further, under CRPs, injuries that are not due to negligence are less likely to become claims because facilities explain to patients what happened; preventing such claims strengthens the informational function of litigation because claims more reliably point to actual quality problems.

Limitations of the Systematic Review

This systematic review has several limitations. First, because studies of deterrence in the malpractice context are published in journals in a wide range of disciplines, there is a risk that some studies were missed. To minimize this risk, we searched multiple databases spanning the medical, public health, economics, business, and legal literatures. Second, some articles reported incomplete or vague information. Articles varied in the amount of detail provided about the data sources, data years analyzed, and model estimation methods employed. Additionally, some did not report full quantitative results for some models, and articles varied in how quantitative results were reported (e.g., with beta coefficients or odds ratios). Third, some articles reported the results of a very large number of different models and model specifications (for example, one reported 84 models 34 ). These circumstances complicated our effort to summarize studies and provide quantitative results that are interpretable and comparable across studies. Fourth, no validated instrument was available for assessing quality or risk of bias in studies of the type included in this review; consequently, this assessment has greater subjectivity than is optimal.

Conclusions

Supplementary material, key points..

Is greater risk of malpractice liability associated with better quality of care?

In this systematic review of 37 studies of obstetrical care outcomes, patient mortality, hospital readmissions, avoidable hospitalizations, and other measures, statistically significant associations between liability risk and quality-related outcome measures were rarely observed. Most studies focused on inpatient care.

Most studies in this review found no association between greater risk of malpractice liability and healthcare quality.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Frakes reported support from the National Institute on Aging, grant R01-AG049898. Dr. Studdert reported receiving grants from the Stanford University Medical Indemnity and Trust Insurance, which is wholly owned by Stanford Hospital and Clinics and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital. Dr. Mello had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The data analysis was performed by M.M., M.F., E.B., and D.S.

Contributor Information

Michelle M. Mello, Stanford Law School, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA; Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA.

Michael D. Frakes, Duke Law School.

Erik Blumenkranz, Stanford Law School, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA

David M. Studdert, Stanford Law School, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA; Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA.

- 1. Keeton WP, Dobbs DB, Keeton RE, Owen DC. Prosser and Keeton on the law of torts. 5th ed. ed. St. Paul, Minn: West Group; 1984. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Brennan TA. Medical malpractice. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(3):283–292. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Grady MF. Better medicine causes more lawsuits, and new administrative courts will not solve the problem. Northwestern Univ Law Rev. 1992;86(4):1068–1093. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Schwartz GT. Reality in the economic analysis of tort law: does tort law really deter? UCLA Law Rev. 1994;42(2):377–444. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1569–1577. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Studdert DM, Mello MM. In from the cold? Law’s evolving role in patient safety. DePaul Law Rev. 2019;68(2):421–458. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Donabedian A The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. B Baicker K, Chandra A. The effect of malpractice liability on the delivery of health care. Forum for Health Econ & Pol’y. 2005;8(1):841–852. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Carlson J, Foster K, Black B, Pines J, Corbit C, Venkat A. Emergency physician practice changes after being named in a malpractice claim. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;__:1–15. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Dhankhar P, Khan MM. Threat of malpractice lawsuit, physician behavior and health outcomes: a re-evaluation of practice of “defensive medicine” in obstetric care. 2009. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1443555 . Accessed June 4, 2019. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Yang YT, Studdert DM, Subramanian SV, Mello MM. Does tort law improve the health of newborns, or miscarry? A longitudinal analysis of the effect of liability pressure on birth outcomes. J Empir Leg Stud. 2012;9(2):217–245. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Entman SS, Glass CA, Hickson GB, Githens PB, Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan FA. The relationship between malpractice claims history and subsequent obstetric care. JAMA. 1994;272(20):1588–1591. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Dubay L, Kaestner R, Waidmann T. The impact of malpractice fears on cesarean section rates. J Health Econ. 1999;18(4):491–522. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Dubay L, Kaestner R, Waidmann T. Medical malpractice liability and its effect on prenatal care utilization and infant health. J Health Econ. 2001;20(4):591–611. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Frakes M, Gruber J. Defensive medicine: evidence from military immunity. 2018. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3218097 . Accessed June 4, 2019. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- 16. Frakes M Defensive medicine and obstetric practices. J Empir Leg Stud. 2012;9(3):457–481. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Frakes M, Jena AB. Does medical malpractice law improve health care quality? J Public Econ. 2016;143:142–158. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Kim B The impact of malpractice risk on the use of obstetrics procedures. J Leg Stud. 2007;36:S79–S119. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Malak N, Yang Y. A re-examination of the effects of tort reforms on obstetrical procedures and health outcomes. Econ Letters. 2019;184:108626. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Sloan FA, Whetten-Goldstein K, Githens PB, Entman SS. Effects of the threat of medical malpractice litigation and other factors on birth outcomes. Med Care. 1995;33(7):700–714. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Sloan FA, Entman SS, Reilly BA, Glass CA, Hickson GB, Zhang HH. Tort liability and obstetricians’ care levels. Int Rev Law Econ. 1997;17(2):245–260. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Klick J, Stratmann T. Medical malpractice reform and physicians in high-risk states. J Leg Stud. 2007;36(2):S121–S142. [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Iizuka T Does higher malpractice pressure deter medical errors? J Law Econ. 2013;56:161–188. [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Zabinski Z, Black BS. The deterrent effect of tort law: evidence from medical malpractice reform. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2161362 . 2018. Accessed June 4, 2019. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ]

- 25. Dhankhar P, Khan MM, Bagga S. Effect of medical malpractice on resource use and mortality of AMI patients. J Empir Leg Stud. 2007;4(1):163–183. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Shepherd JM. Tort reforms’ winners and losers: the competing effects of care and activity levels. UCLA Law Rev. 2008;55(4):905–977. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Lakdawalla DN, Seabury SA. The welfare effects of medical malpractice liability. Int Rev Law Econ. 2012;32(4):356–369. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Bilimoria KY, Chung JW, Minami CA, et al. Relationship between state malpractice environment and quality of health care in the United States. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(5):241–250. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Konety BR, Dhawan V, Allareddy V, Joslyn SA. Impact of malpractice caps on use and outcomes of radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: data from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. J Urol. 2005;173(6):2085–2089. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Bekelis K, Missios S, Wong K, MacKenzie TA. The practice of cranial neurosurgery and the malpractice liability environment in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0121191. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Baicker K, Fisher ES, Chandra A. Malpractice liability costs and the practice of medicine in the Medicare program. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(3):841–852. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Moghtaderi A, Farmer S, Black B. Damage caps and defensive medicine: reexamination with patient-level data. J Empir Leg Stud. 2019;16(1):26–68. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Bilimoria KY, Sohn M-W, Chung JW, et al. Association between state medical malpractice environment and surgical quality and cost in the United States. Ann Surg. 2016;263(6):1126–1132. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Minami CA, Sheils CR, Pavey E, et al. Association Between State Medical Malpractice Environment and Postoperative Outcomes in the United States. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(3):310–318 e312. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Stevenson DG, Spittal MJ, Studdert DM. Does litigation increase or decrease health care quality?: a national study of negligence claims against nursing homes. Med Care. 2013;51(5):430–436. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Konetzka RT, Park J, Ellis R, Abbo E. Malpractice litigation and nursing home quality of care. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 1):1920–1938. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Yang YT, Mello MM, Subramanian SV, Studdert DM. Relationship between malpractice litigation pressure and rates of cesarean section and vaginal birth after cesarean section. Med Care. 2009;47(2):234–242. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Black BS, Wagner AR, Zabinski Z. The association between Patient Safety Indicators and medical malpractice risk: evidence from Florida and Texas. Am J Health Econ. 2017;3(2):109–139. [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Mello MM, Hemenway D. Medical malpractice as an epidemiological problem. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(1):39–46. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Sedgwick P Ecological studies: advantages and disadvantages. BMJ. 2014;348:g2979. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Kessler D, McClellan M. Do doctors practice defensive medicine? Q J Econ. 1996;111:353–390. [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Kessler D, McClellan M. Malpractice law and health care reform: optimal liability policy in an era of managed care. J Public Econ. 2002;84(2):175–197. [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Avraham R, Schanzenbach M. The impact of tort reform on intensity of treatment: Evidence from heart patients. J Health Econ. 2015;39:273–288. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Missios S, Bekelis K. Spine surgery and malpractice liability in the United States. Spine J. 2015;15(7):1602–1608. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Mello MM, Brennan TA. Deterrence of medical errors: Theory and evidence for malpractice reform. Tex Law Rev. 2002;80(7):1595–1637. [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Hyman DA, Black B, Zeiler K, Silver C, Sage WM. Do defendants pay what juries award? Post‐verdict haircuts in Texas medical malpractice cases, 1988–2003. J Empir Leg Stud. 2007;4(1):3–68. [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Dranove D, Ramanarayanan S, Watanabe Y. Delivering bad news: market responses to negligence. J Law Econ. 2012;55(1):1–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Charles SC, Pyskoty CE, Nelson A. Physicians on trial--self-reported reactions to malpractice trials. West J Med. 1988;148(3):358–360. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Balch CM, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Personal consequences of malpractice lawsuits on American surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(5):657–667. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2000. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA. 1994;272(23):1851–1857. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Boothman RC, Blackwell AC, Campbell DA Jr., Commiskey E, Anderson S. A better approach to medical malpractice claims? The University of Michigan experience. J Health Life Sci Law. 2009;2(2):125–159. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Currie J, MacLeod WB. First do no harm? Tort reform and birth outcomes. Q J Econ. 2008;123(2):795–830. [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Sloan FA, Shadle JH. Is there empirical evidence for “defensive medicine”? A reassessment. J Health Econ. 2009;28(2):481–491. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Bartlett B Legal epidemiology and the correlation of patient safety, deterrence, and defensive medicine. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2807689 . 2017. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- 56. McMichael B The failure of “sorry”: an empirical evaluation of apology laws, health care, and medical malpractice. Lewis & Clark Law Rev. 2018;22(4):11991281. [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (726.6 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Malpractice Liability and Health Care Quality: A Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Stanford Law School, Stanford, California.

- 2 Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California.

- 3 Duke University School of Law, Durham, North Carolina.

- PMID: 31990319

- PMCID: PMC7402204

- DOI: 10.1001/jama.2019.21411

Importance: The tort liability system is intended to serve 3 functions: compensate patients who sustain injury from negligence, provide corrective justice, and deter negligence. Deterrence, in theory, occurs because clinicians know that they may experience adverse consequences if they negligently injure patients.

Objective: To review empirical findings regarding the association between malpractice liability risk (ie, the extent to which clinicians face the threat of being sued and having to pay damages) and health care quality and safety.

Data sources and study selection: Systematic search of multiple databases for studies published between January 1, 1990, and November 25, 2019, examining the relationship between malpractice liability risk measures and health outcomes or structural and process indicators of health care quality.

Data extraction and synthesis: Information on the exposure and outcome measures, results, and acknowledged limitations was extracted by 2 reviewers. Meta-analytic pooling was not possible due to variations in study designs; therefore, studies were summarized descriptively and assessed qualitatively.

Main outcomes and measures: Associations between malpractice risk measures and health care quality and safety outcomes. Exposure measures included physicians' malpractice insurance premiums, state tort reforms, frequency of paid claims, average claim payment, physicians' claims history, total malpractice payments, jury awards, the presence of an immunity from malpractice liability, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services' Medicare malpractice geographic practice cost index, and composite measures combining these measures. Outcome measures included patient mortality; hospital readmissions, avoidable admissions, and prolonged length of stay; receipt of cancer screening; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality patient safety indicators and other measures of adverse events; measures of hospital and nursing home quality; and patient satisfaction.

Results: Thirty-seven studies were included; 28 examined hospital care only and 16 focused on obstetrical care. Among obstetrical care studies, 9 found no significant association between liability risk and outcomes (such as Apgar score and birth injuries) and 7 found limited evidence for an association. Among 20 studies of patient mortality in nonobstetrical care settings, 15 found no evidence of an association with liability risk and 5 found limited evidence. Among 7 studies that examined hospital readmissions and avoidable initial hospitalizations, none found evidence of an association between liability risk and outcomes. Among 12 studies of other measures (eg, patient safety indicators, process-of-care quality measures, patient satisfaction), 7 found no association between liability risk and these outcomes and 5 identified significant associations in some analyses.

Conclusions and relevance: In this systematic review, most studies found no association between measures of malpractice liability risk and health care quality and outcomes. Although gaps in the evidence remain, the available findings suggested that greater tort liability, at least in its current form, was not associated with improved quality of care.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Insurance, Liability / economics

- Liability, Legal*

- Malpractice / economics

- Malpractice / legislation & jurisprudence*

- Malpractice / statistics & numerical data

- Obstetrics / standards

- Outcome Assessment, Health Care

- Postoperative Complications

- Quality of Health Care*

Grants and funding

- R01 AG049898/AG/NIA NIH HHS/United States

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Feb 13, 2020 · Richard Griffith , Senior Lecturer in Health Law at Swansea University, discusses the circumstances that give rise to a duty of care and the standard expected of nurses in discharging their duty. Br J Nurs .

More and more nurses are being named defendants in malpractice lawsuits, according to the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB). From 1998 to 2001, for instance, the number of malpractice payments made by nurses increased from 253 to 413 (see Figure 1, page 55).

This systematic review has several limitations. First, because studies of deterrence in the malpractice context are published in journals in a wide range of disciplines, there is a risk that some studies were missed. To minimize this risk, we searched multiple databases spanning the medical, public health, economics, business, and legal ...

Jan 28, 2020 · In this systematic review, most studies found no association between measures of malpractice liability risk and health care quality and outcomes. Although gaps in the evidence remain, the available findings suggested that greater tort liability, at least in its current form, was not associated with …

therefore, a proven malpractice liability by a powerful and recognized authority such as regulatory bodies or judicial court against RNwill be the only evidences of malpractice17.Any errors that do not match the below criteria will not be considered malpractice13,17–23: 1. Nursing care that was provided to the patient by RN .

negligence, malpractice, assault, battery, false imprisonment, defamation of character, fraud, invasion of privacy, informed consent, physician order and carrying out medical procedures by doctor order, staffing issues (nursing assignment, nursing shortage, abandonment, and improper delegation and supervision), suit-prone

Nurses, Negligence, and Malpractice: An analysis based on more than 250 cases against nurses. The Elements of a Nursing Malpractice Case, Part 1: Duty; The Elements of a Nursing Malpractice Case, Part 3B: Causation; Ethical Issues; Lessons Learned from Litigation: Legal and Ethical Consequences of Social Media

May 1, 2020 · Background. Medical malpractice data can be used to improve patient safety.Objective. To describe the types of harm events involving nurses that lead to malpractice claims and to compare claims among intensive care units (ICUs), emergency departments, and operating rooms.Methods. Malpractice claims closed between 2007 and 2016 were extracted from a national database. Claims with a nurse as the ...

Jul 1, 2017 · A review of the literature indicates that nurse practitioner malpractice studies most frequently focus on tabulating and comparing rates and types of claims by provider type, specifically nurse practitioners, physician assistants and physicians (Brock et al., 2016, Miller, 2013, Miller, 2012, Miller, 2011, Hooker et al., 2009, Carson-Smith and Klein, 2003, Birkholz, 1995).

Analysts reviewed 4,634 malpractice claims settled between 2018 and 2021. Of these cases, 850 (18%) of the adverse events directly involved nursing personnel, including RNs, LPNs, nursing assistants, and nursing students. The majority of nursing-related errors (65%) occurred in inpatient settings, with 66% of them taking place in the patient's ...