PERSPECTIVE article

The rise and impact of covid-19 in india.

- 1 School of Biosciences and Technology, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, India

- 2 VIT-BS, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, India

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, which originated in the city of Wuhan, China, has quickly spread to various countries, with many cases having been reported worldwide. As of May 8th, 2020, in India, 56,342 positive cases have been reported. India, with a population of more than 1.34 billion—the second largest population in the world—will have difficulty in controlling the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 among its population. Multiple strategies would be highly necessary to handle the current outbreak; these include computational modeling, statistical tools, and quantitative analyses to control the spread as well as the rapid development of a new treatment. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of India has raised awareness about the recent outbreak and has taken necessary actions to control the spread of COVID-19. The central and state governments are taking several measures and formulating several wartime protocols to achieve this goal. Moreover, the Indian government implemented a 55-days lockdown throughout the country that started on March 25th, 2020, to reduce the transmission of the virus. This outbreak is inextricably linked to the economy of the nation, as it has dramatically impeded industrial sectors because people worldwide are currently cautious about engaging in business in the affected regions.

Current Scenario in India

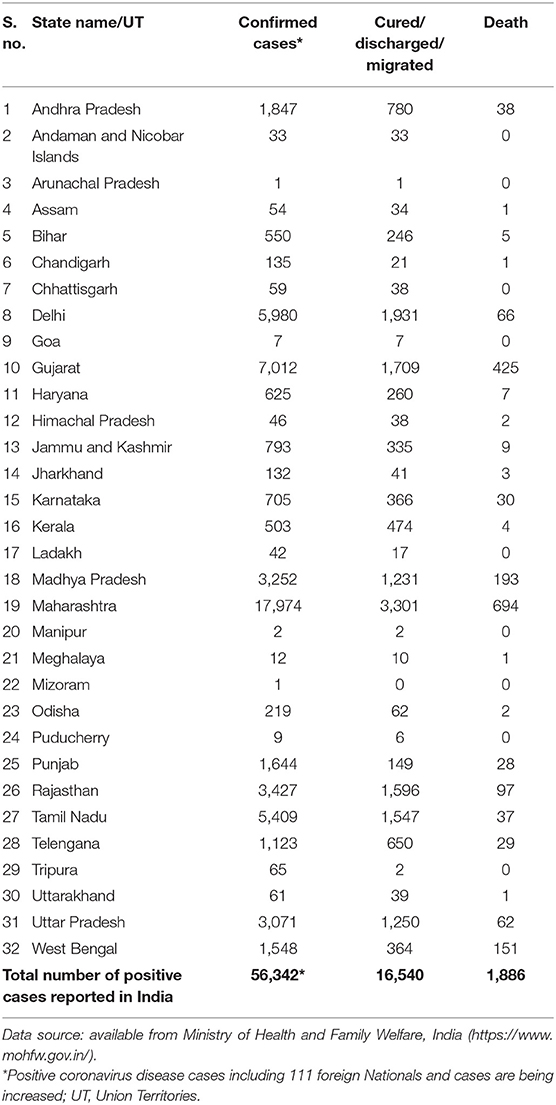

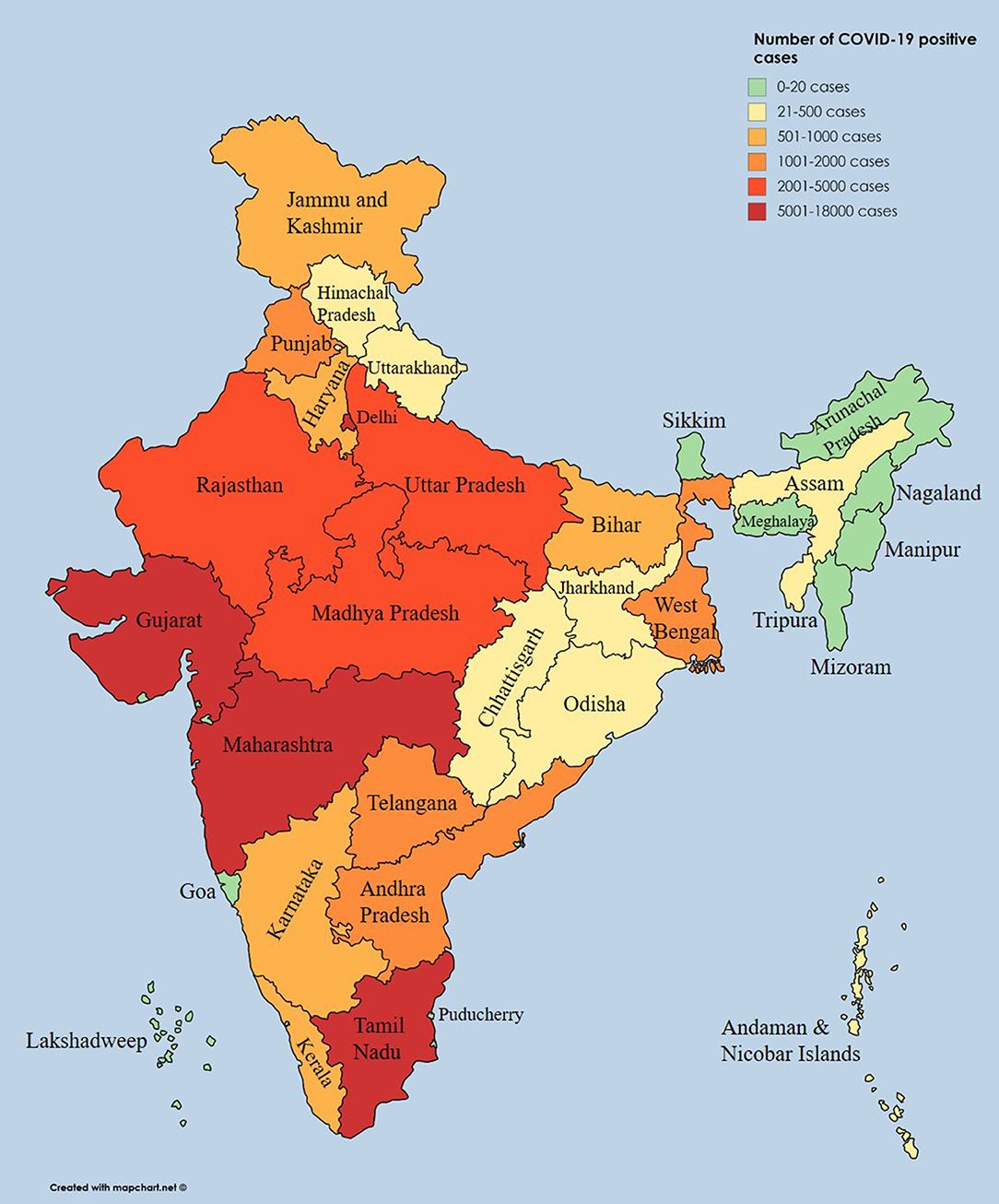

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes coronavirus disease (COVID-19), was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan city, China, and later spread to many provinces in China. As of May 8th, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) had documented 3,759,967 positive COVID-19 cases, and the death toll attributed to COVID-19 had reached 259,474 worldwide ( 1 ). So far, more than 212 countries and territories have confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection. On January 30th, 2020, the WHO declared COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern ( 2 ). The first SARS-CoV-2 positive case in India was reported in the state of Kerala on January 30th, 2020. Subsequently, the number of cases drastically rose. According to the press release by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) on May 8th, 2020, a total of 14,37,788 suspected samples had been sent to the National Institute of Virology (NIV), Pune, and a related testing laboratory ( 3 ). Among them, 56,342 cases tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 ( 4 ). A state-wise distribution of positive cases until May 8th, 2020, is listed in Table 1 , and the cases have been depicted on an Indian map ( Figure 1 ). Nearly 197,192 Indians have recently been repatriated from affected regions, and more than 1,393,301 passengers have been screened for SARS-CoV-2 at Indian airports ( 5 ), with 111 positive cases observed among foreign nationals ( 4 , 5 ). As of May 8th, 2020, Maharashtra, Delhi, and Gujarat states were reported to be hotspots for COVID-19 with 17,974, 5,980, and 7,012 confirmed cases, respectively. To date, 16,540 patients have recovered, and 1,886 deaths have been reported in India ( 5 ). To impose social distancing, the “Janata curfew” (14-h lockdown) was ordered on March 22nd, 2020. A further lockdown was initiated for 21 days, starting on March 25th, 2020, and the same was extended until May 3rd, 2020, but, owing to an increasing number of positive cases, the lockdown has been extended for the third time until May 17th, 2020 ( 6 ). Currently, out of 32 states and eight union territories in India, 26 states and six union territories have reported COVID-19 cases. Additionally, the health ministry has identified 130 districts as hotspot zones or red zones, 284 as orange zones (with few SARS-CoV-2 infections), and 319 as green zones (no SARS-CoV-2 infection) as of May 4th, 2020. These hotspot districts have been identified to report more than 80% of the cases across the nation. Nineteen districts in Uttar Pradesh are identified as hotspot districts, and this was followed by 14 and 12 districts in Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, respectively ( 7 ). The complete lockdown was implemented in these containment zones to stop/limit community transmission ( 5 ). As of May 8th, 2020, 310 government laboratories and 111 private laboratories across the country were involved in SARS-CoV-2 testing. As per ICMR report, 14,37,788 samples were tested till date, which is 1.04 per thousand people ( 3 ).

Table 1 . Current status of reported positive coronavirus disease cases in India (State-wise).

Figure 1 . State-wise distribution of positive coronavirus disease cases displayed on an Indian geographical map.

COVID-19 and Previous Coronavirus Outbreaks

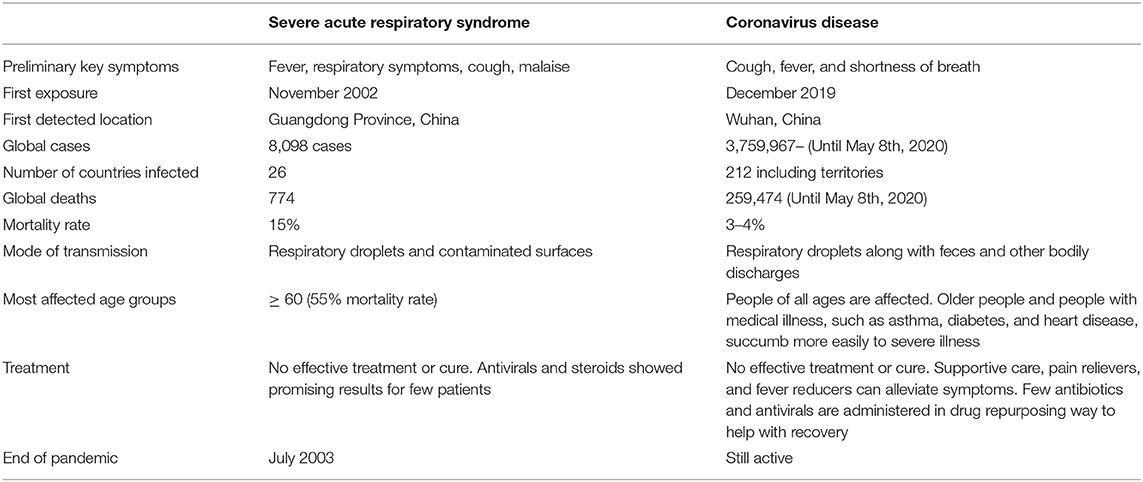

The recent outbreak of COVID-19 in several countries is similar to the previous outbreaks of SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) that emerged in 2003 and 2012 in China and Saudi Arabia, respectively ( 8 – 10 ). Coronavirus is responsible for both SARS and COVID-19 diseases; they affect the respiratory tract and cause major disease outbreaks worldwide. SARS is caused by SARS-CoV, whereas SARS-CoV-2 causes COVID-19. So far, there is no particular treatment available to treat SARS or COVID-19. In the current search for a COVID-19 cure, there is some evidence that point to SARS-CoV-2 being similar to human coronavirus HKU1 and 229E strains ( 11 , 12 ) even though they are new coronavirus family members. These reports suggest that humans do not have immunity to this virus, allowing its easy and rapid spread among human populations through contact with an infected person. SARS-CoV-2 is more transmissible than SARS-CoV. The two possible reasons could be (i) the viral load (quantity of virus) tends to be relatively higher in COVID-19-positive patients, especially in the nose and throat immediately after they develop symptoms, and (ii) the binding affinity of SARS-CoV-2 to host cell receptors is higher than that of SARS-CoV ( 13 , 14 ). The other comparisons between SARS and COVID-19 are tabulated in Table 2 , and references for the same are provided here ( 1 , 15 , 16 ).

Table 2 . Differences between coronavirus disease and severe acute respiratory syndrome.

Impact of COVID-19 in India and the Global Economy

As per the official government guidelines, India is making preparations against the COVID-19 outbreak, and avoiding specific crisis actions or not understating its importance will have extremely severe implications. All the neighboring countries of India have reported positive COVID-19 cases. To protect against the deadly virus, the Indian government have taken necessary and strict measures, including establishing health check posts between the national borders to test whether people entering the country have the virus ( 17 ). Different countries have introduced rescue efforts and surveillance measures for citizens wishing to return from China. The lesson learned from the SARS outbreak was first that the lack of clarity and information about SARS weakened China's global standing and hampered its economic growth ( 10 , 18 – 20 ). The outbreak of SARS in China was catastrophic and has led to changes in health care and medical systems ( 18 , 20 ). Compared with China, the ability of India to counter a pandemic seems to be much lower. A recent study reported that affected family members had not visit the Wuhan market in China, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 may spread without manifesting symptoms ( 21 ). Researchers believe that this phenomenon is normal for many viruses. India, with a population of more than 1.34 billion—the second largest population in the world—will have difficulty treating severe COVID-19 cases because the country has only 49,000 ventilators, which is a minimal amount. If the number of COVID-19 cases increases in the nation, it would be a catastrophe for India ( 22 ). It would be difficult to identify sources of infection and those who come in contact with them. This would necessitate multiple strategies to handle the outbreak, including computational modeling as well as statistical and quantitative analyses, to rapidly develop new vaccines and drug treatments. With such a vast population, India's medical system is grossly inadequate. A study has shown that, owing to inadequate medical care systems, nearly 1 million people die every year in India ( 23 ). India is also engaged in trading with its nearby countries, such as Bangladesh, Bhutan, Pakistan, Myanmar, China, and Nepal. During the financial year 2017–18 (FY2017–18), Indian regional trade amounted to nearly $12 billion, accounting for only 1.56% of its total global trade value of $769 billion. The outbreak of such viruses and their transmission would significantly affect the Indian economy. The outbreak in China could profoundly affect the Indian economy, especially in the sectors of electronics, pharmaceuticals, and logistics operations, as trade ports with China are currently closed. This was further supported by the statement by Suyash Choudhary, Head—Fixed Income, IDFC AMC, stating that GDP might decrease owing to COVID-19 ( 24 ).

Economists assume that the impact of COVID-19 on the economy will be high and negative when compared with the SARS impact during 2003. For instance, it has been estimated that the number of tourists arriving in China was much higher than that of tourists who traveled during the season when SARS emerged in 2003. This shows that COVID-19 has an effect on the tourism industry. It has been estimated that, for SARS, there was a 57 and 45% decline in yearly rail passenger and road passenger traffic, respectively ( 25 ). Moreover, when compared with the world economy 15 years ago, world economies are currently much more inter-related. It has been estimated that COVID-19 will hurt emerging market currencies and also impact oil prices ( 26 – 28 ). From the retail industry's perspective, consumer savings seem to be high. This might have an adverse effect on consumption rates, as all supply chains are likely to be affected, which in turn would have its impact on supply when compared with the demand of various necessary product items ( 29 ). This clearly proves that, based on the estimated losses due to the effect of SARS on tourism (retail sales lost around USD 12–18 billion and USD 30–100 billion was lost at a global macroeconomic level), we cannot estimate the impact of COVID-19 at this point. This will be possible only when the spread of COVID-19 is fully controlled. Until that time, any estimates will be rather ambiguous and imprecise ( 19 ). The OECD Interim economic assessment has provided briefing reports highlighting the role of China in the global supply chain and commodity markets. Japan, South Korea, and Australia are the countries that are most susceptible to adverse effects, as they have close ties with China. It has been estimated that there has been a 20% decline in car sales, which was 10% of the monthly decline in China during January 2020. This shows that even industrial production has been affected by COVID-19. So far, several factors have thus been identified as having a major economic impact: labor mobility, lack of working hours, interruptions in the global supply chain, less consumption, and tourism, and less demand in the commodity market at a global level ( 30 ), which in turn need to be adequately analyzed by industry type. Corporate leaders need to prioritize the supply chain and product line economy trends via demand from the consumer end. Amidst several debates on sustainable economy before the COVID-19 impact, it has now been estimated that India's GDP by the International Monetary Fund has been cut down to 1.9% from 5.8% for the FY21. The financial crisis that has emerged owing to the worldwide lockdown reflects its adverse effect on several industries and the global supply chain, which has resulted in the GDP dropping to 4.2% for FY20, which was previously estimated at 4.8%. Nevertheless, it has been roughly estimated that India and China will be experiencing considerable positive growth among other major economies ( 31 ).

Preparations and Preventive Measures in India

An easy way to decrease SARS-CoV-2 infection rates is to avoid virus exposure. People from India should avoid traveling to countries highly affected with the virus, practice proper hygiene, and avoid consuming food that is not home cooked. Necessary preventive measures, such as wearing a mask, regular hand washing, and avoiding direct contact with infected persons, should also be practiced. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW), India, has raised awareness about the recent outbreak and taken necessary action to control COVID-19. Besides, the MOHFW has created a 24 h/7 days-a-week disease alert helpline (+91-11-23978046 and 1800-180-1104) and policy guidelines on surveillance, clinical management, infection prevention and control, sample collection, transportation, and discharging suspected or confirmed cases ( 3 , 5 ). Those who traveled from China, or other countries, and exhibited symptoms, including fever, difficulty in breathing, sore throat, cough, and breathlessness, were asked to visit the nearest hospital for a health check-up. Officials from seven different airports, including Chennai, Cochin, New Delhi, Kolkata, Hyderabad, and Bengaluru, have been ordered to screen and monitor Indian travelers from China and other affected countries. In addition, a travel advisory was released to request the cessation of travel to affected countries, and anyone with a travel history that has included China since January 15th, 2020, would be quarantined. A centralized control room has been set up by the Delhi government at the Directorate General of Health Services, and 11 other districts have done the same. India has implemented COVID-19 travel advisory for intra- and inter-passenger aircraft restrictions. More information on additional travel advisory can be accessed with the provided link ( https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Traveladvisory.pdf ).

India is known for its traditional medicines in the form of AYUSH (Ayurvedic, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy). The polyherbal powder NilavembuKudineer showed promising effects against dengue and chikungunya fevers in the past ( 32 ). With the outbreak of COVID-19, the ministry of AYUSH has released a press note “Advisory for Coronavirus,” mentioning useful medications to improve the immunity of the individuals ( 33 ). Currently, according to the ICMR guidelines, doctors prescribe a combination of Lopinavir and Ritonavir for severe COVID-19 cases and hydroxychloroquine for prophylaxis of SARS-CoV-2 infection ( 34 , 35 ). In collaboration with the WHO, ICMR will conduct a therapeutic trial for COVID-19 in India ( 3 ). The ICMR recommends using the US-FDA-approved closed real-time RT-PCR systems, such as GeneXpert and Roche COBAS-6800/8800, which are used to diagnose chronic myeloid leukemia and melanoma, respectively ( 36 ). In addition, the TruenatTM beta CoV test on the TruelabTM workstation validated by the ICMR is recommended as a screening test. All positive results obtained on this platform need to be confirmed by confirmatory assays for SARS-CoV-2. All negative results do not require further testing. Antibody-based rapid tests were validated at NIV, Pune, and found to be satisfactory; the rapid test kits are as follows: (i) SARS-CoV-2 Antibody test (Lateral flow method): Guangzhou Wondfo Biotech, Mylan Laboratories Limited (CE-IVD); (ii) COVID-19 IgM&IgG Rapid Test: BioMedomics (CE-IVD); (iii) COVID-19 IgM/IgG Antibody Rapid Test: Zhuhai Livzon Diagnostics (CEIVD); (iv) New coronavirus (COVID-19) IgG/IgM Rapid Test: Voxtur Bio Ltd, India; (v) COVID-19 IgM/IgG antibody detection card test: VANGUARD Diagnostics, India; (vi) MakesureCOVID-19 Rapid test: HLL Lifecare Limited, India; and (vii) YHLO SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG detection kit (additional equipment required): CPC, Diagnostics. As a step further, on the technological aspect, the Union Health Ministry has launched a mobile application called “AarogyaSetu” that works both on android and iOS mobile phones. This application constructs a user database for establishing an awareness network that can alert people and governments about possible COVID-19 victims ( 37 ).

Future Perspectives

Infections caused by these viruses are an enormous global health threat. They are a major cause of death and have adverse socio-economic effects that are continually exacerbated. Therefore, potential treatment initiatives and approaches need to be developed. First, India is taking necessary preventive measures to reduce viral transmission. Second, ICMR and the Ministry of AYUSH provided guidelines to use conventional preventive and treatment strategies to increase immunity against COVID-19 ( 3 , 38 ). These guidelines could help reduce the severity of the viral infection in elderly patients and increase life expectancy ( 39 ). The recent report from the director of ICMR mentioned that India would undergo randomized controlled trials using convalescent plasma of completely recovered COVID-19 patients. Convalescent plasma therapy is highly recommended, as it has provided moderate success with SARS and MERS ( 40 ); this has been rolled out in 20 health centers and will be increased this month (May 2020) ( 3 ). India has expertise in specialized medical/pharmaceutical industries with production facilities, and the government has established fast-tracking research to develop rapid diagnostic test kits and vaccines at low cost ( 41 ). In addition, the Serum Institute of India started developing a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection ( 42 ). Until we obtain an appropriate vaccine, it is highly recommended that we screen the red zoned areas to stop further transmission of the virus. Medical college doctors in Kerala, India, implemented the low-cost WISK (Walk-in Sample Kiosk) to collect samples without direct exposure or contact ( 43 , 44 ). After Kerala, The Defense Research and Development Organization (DRDO) developed walk-in kiosks to collect COVID-19 samples and named these as COVID-19 Sample Collection Kiosk (COVSACK) ( 45 ). After the swab collection, the testing of SARS-CoV-2 can be achieved with the existing diagnostic facility in India. This facility can be used for massive screening or at least in the red zoned areas without the need for personal protective equipment kits ( 43 , 45 ). India has attempted to broaden its research facilities and shift toward testing the mass population, as recommended by medical experts in India and worldwide ( 46 ).

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/ and https://www.icmr.gov.in/ .

Author Contributions

SK, DK, and CD were involved in the design of the study and the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of the data, and drafting the manuscript. BC was involved in the interpretation of the data. CD supervised the entire study. The manuscript was reviewed and approved by all the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) and Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for publicly providing the details of COVID-19. The authors would like to use this opportunity to thank the management of VIT for providing the necessary facilities and encouragement to carry out this work.

1. Situation report-109. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) . WHO (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed May 09, 2020).

2. Wee SL Jr, McNeil DG Jr, Hernández JC. W.H.O. Declares Global Emergency as Wuhan Coronavirus Spreads . The New York Times (2020). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/30/health/coronavirus-world-health-organization.html (accessed February 03, 2020).

3. COVID-19 ICMR. COVID-19 . Indian Council of Medical Research. Government of India. ICMR (2020). Available online at: https://main.icmr.nic.in/content/covid-19 (accessed May 09, 2020).

4. COVID-19 update. COVID-19 INDIA . Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. MOHFW (2020). Available online at: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/ (accessed May 09, 2020).

5. Novel coronavirus-MOHFW. Home . Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. GOI (2020). Available online at: http://www.mohfw.gov.in/ (accessed May 08, 2020).

6. Bureau O. PM Modi calls for ‘Janata curfew’ on March 22 from 7 AM-9 PM . @businessline (2020). Available online at: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/pm-modi-calls-for-janta-curfew-on-march-22-from-7-am-9-pm/article31110155.ece (accessed April 05, 2020).

7. Sangeeta N. Coronavirus Hotspots in India: Full List of 130 COVID-19 Hotspot Districts, All Metro Cities Marked Red Zones . Jagranjosh.com (2020). Available online at: https://www.jagranjosh.com/current-affairs/coronavirus-hotspot-areas-in-india-what-are-hotspots-know-all-covid-hotspots-1586411869-1 (accessed May 03, 2020).

8. Smith RD. Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks: lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management. Soc Sci Med. (2006) 63:3113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Mackay IM, Arden KE. MERS coronavirus: diagnostics, epidemiology and transmission. Virol J. (2015) 12:222. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0439-5

10. Peeri NC, Shrestha N, Rahman MS, Zaki R, Tan Z, Bibi S, et al. The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? Int J Epidemiol . (2020). doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa033. [Epub ahead of print].

11. Broor S, Dawood FS, Pandey BG, Saha S, Gupta V, Krishnan A, et al. Rates of respiratory virus-associated hospitalization in children aged <5 years in rural northern India. J Infection. (2014) 68:281–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.11.005

12. Sonawane AA, Shastri J, Bavdekar SB. Respiratory pathogens in infants diagnosed with acute lower respiratory tract infection in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Western India Using Multiplex Real Time PCR. Indian J Pediatr. (2019) 86:433–8. doi: 10.1007/s12098-018-2840-8

13. Tai W, He L, Zhang X, Pu J, Voronin D, Jiang S, et al. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell Mol Immunol. (2020). doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0400-4. [Epub ahead of print].

14. Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1177–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737

15. Emergencies preparedness, response. WHO | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)-multi-country outbreak - Update 55 . WHO (2003). Available online at: https://www.who.int/csr/don/2003_05_14a/en/ (accessed February 03, 2020).

Google Scholar

16. CDC. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) – Symptoms . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html (accessed April 07, 2020).

17. Qayam. Coronavirus scare in east UP due to cases in Nepal . The Siasat Daily (2020). Available online at: https://www.siasat.com/coronavirus-scare-east-due-cases-nepal-1805965/ (accessed February 03, 2020).

18. Huang Y. The Sars Epidemic And Its Aftermath In China: A Political Perspective . National Academies Press (US) (2004). Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92479/ (accessed May 04, 2020).

19. Qiu W, Chu C, Mao A, Wu J. The impacts on health, society, and economy of SARS and H7N9 outbreaks in China: a case comparison study. J Environ Public Health. (2018) 2018:e2710185. doi: 10.1155/2018/2710185

20. McCloskey B, Heymann DL. SARS to novel coronavirus–old lessons and new lessons. Epidemiol Infect . (2020) 148:e22. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820000254

21. Chan JF-W, Yuan S, Kok K-H, To KK-W, Chu H, Yang J, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. (2020) 395:514–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9

22. PIB Mubmai. Press Information Bureau . Press Information Bureau (2020). Available online at: https://pib.gov.in/indexd.aspx (accessed May 05, 2020).

23. Dandona L, Dandona R, Kumar GA, Shukla DK, Paul VK, Balakrishnan K, et al. Nations within a nation: variations in epidemiological transition across the states of India, 1990–2016 in the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. (2017) 390:2437–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32804-0

24. Samrat S. Coronavirus may hit Sitharaman's 10% growth target; second case surfaces in India . The Financial Express (2020). Available online at: https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/coronavirus-may-hit-sitharamans-10-gdp-growth-target-second-case-surfaces-in-india/1852146/ (accessed February 03, 2020).

25. Cheng E, Tan W. Coronavirus cases in China overtake SARS — and the economic impact could be “more severe.” CNBC (2020). Available online at: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/29/coronavirus-cases-in-china-overtake-sars-and-impact-could-be-more-severe.html (accessed March 11, 2020).

26. Atsmon Y, Child P, Dobbs R, Narasimhan L. Winning the $30 Trillion Decathlon: Going for Gold in Emerging Markets . McKinsey (2012). Available online at: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/winning-the-30-trillion-decathlon-going-for-gold-in-emerging-markets (accessed May 04, 2020).

27. Sudhir K, Priester J, Shum M, Atkin D, Foster A, Iyer G, et al. Research opportunities in emerging markets: an inter-disciplinary perspective from marketing, economics, and psychology. Cust Need Solut. (2015) 2:264–76. doi: 10.1007/s40547-015-0044-1

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Albulescu C. Coronavirus and oil price crash. SSRN J. (2020) 1–13. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3553452

29. Carlsson-Szlezak P, Reeves M, Swartz P. What Coronavirus Could Mean for the Global Economy . Harvard Business Review (2020). Available online at: https://hbr.org/2020/03/what-coronavirus-could-mean-for-the-global-economy (accessed March 11, 2020).

30. Coronavirus: The world economy at risk. (2020). OECD Economic Outlook . Available online at: http://www.oecd.org/economic-outlook/ (accessed March 11, 2020).

31. International Monetary Fund. (2020). “Chapter 1-policies to support people during the COVID-19 pandemic,” in FISCAL MONITOR (International Monetary Fund). Available online at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications (accessed May 07, 2020).

32. Jain J, Kumar A, Narayanan V, Ramaswamy RS, Sathiyarajeswaran P, Shree Devi MS, et al. Antiviral activity of ethanolic extract of Nilavembu Kudineer against dengue and chikungunya virus through in vitro evaluation. J Ayurveda Integr Med . (2019). doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2018.05.006. [Epub ahead of print].

33. Advisory for Corona virus, Homoeopathy for Prevention of Corona virus Infections, Unani Medicines useful in symptomatic management of Corona Virus infection. Press Information Bureau . Available online at: pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1600895 (accessed February 03, 2020).

34. Bhatnagar T, Murhekar MV, Soneja M, Gupta N, Giri S, Wig N, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir combination therapy amongst symptomatic coronavirus disease 2019 patients in India: protocol for restricted public health emergency use. Indian J Med Res . (2020) 151:184–9. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_502_20

35. Rathi S, Ish P, Kalantri A, Kalantri S. Hydroxychloroquine prophylaxis for COVID-19 contacts in India. Lancet Infectious Dis. (2020). doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30313-3. [Epub ahead of print].

36. Health C. for D. and R. Nucleic Acid Based Tests . FDA (2020). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/vitro-diagnostics/nucleic-acid-based-tests (accessed May 05, 2020).

37. Aarogya Setu Mobile App. MyGov.in . (2020). Available online at: https://mygov.in/aarogya-setu-app/ (accessed May 04, 2020).

PubMed Abstract

38. Vasudha V. Coronavirus Outbreak: Ayush Pushes “Traditional Cure,” Med Council Backs Modern Drugs . The Economic Times (2020). Available online at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/ayush-pushes-traditional-cure-med-council-backs-modern-drugs/articleshow/74680699.cms (accessed May 02, 2020).

39. Elfiky AA. Anti-HCV, nucleotide inhibitors, repurposing against COVID-19. Life Sci. (2020) 248:117477. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117477

40. Teixeira da Silva JA. Convalescent plasma: a possible treatment of COVID-19 in India. Med J Armed Forces India . (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.04.006. [Epub ahead of print].

41. Sinha DK. COVID-19: Vaccine Development and Therapeutic Strategies . IndiaBioscience (2020). Available online at: https://indiabioscience.org/columns/general-science/covid-19-vaccine-development-and-therapeutic-strategies (accessed May 06, 2020).

42. Varghese MG, Rijal S. How India Must Prepare for a Second Wave of COVID-19 . Nature India (2020). Available online at: https://www.natureasia.com/en/nindia/article/10.1038/nindia.2020.80 (accessed May 06, 2020).

43. Koshy SM. Inspired By South Korea, Walk-In COVID-19 Test Kiosks Built In Kerala . NDTV.com (2020). Available online at: https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/coronavirus-inspired-by-south-korea-walk-in-test-kiosks-built-in-keralas-ernakulam-2207119 (accessed May 06, 2020).

44. MK N. Covid-19: Kerala Hospital Installs South Korea-Like Kiosks to Collect Samples . Livemint (2020). Available online at: https://www.livemint.com/news/india/covid-19-kerala-hospital-installs-south-korea-like-kiosks-to-collect-samples-11586234679849.html (accessed May 09, 2020).

45. DRDO. Covid-19 Sample Collection Kiosk (COVSACK) . Defence Research and Development Organisation - DRDO|GoI (2020). Available online at: https://drdo.gov.in/covid-19-sample-collection-kiosk-covsack (accessed May 09, 2020).

46. Vaidyanathan G. People power: how India is attempting to slow the coronavirus. Nature. (2020) 580:442. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01058-5

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, India, economy, safety measures

Citation: Kumar SU, Kumar DT, Christopher BP and Doss CGP (2020) The Rise and Impact of COVID-19 in India. Front. Med. 7:250. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00250

Received: 19 March 2020; Accepted: 11 May 2020; Published: 22 May 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Kumar, Kumar, Christopher and Doss. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: C. George Priya Doss, georgepriyadoss@vit.ac.in

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Publications

- Ask a question

- Research Hub

- Submit Evidence

How has Covid-19 affected India’s economy?

India has been hit hard by the pandemic, particularly during the second wave of the virus in the spring of 2021. the sharp drop in gdp is the largest in the country’s history, but this may still underestimate the economic damage experienced by the poorest households..

From April to June 2020, India’s GDP dropped by a massive 24.4%. According to the latest national income estimates , in the second quarter of the 2020/21 financial year (July to September 2020), the economy contracted by a further 7.4%. The recovery in the third and fourth quarters (October 2020 to March 2021) was still weak, with GDP rising 0.5% and 1.6%, respectively. This means that the overall rate of contraction in India was (in real terms) 7.3% for the whole 2020/21 financial year.

In the post-independence period, India's national income has declined only four times before 2020 – in 1958, 1966, 1973 and 1980 – with the largest drop being in 1980 (5.2%). This means that 2020/21 is the worst year in terms of economic contraction in the country’s history, and much worse than the overall contraction in the world (Figure 1).

The decline is solely responsible for reversing the trend in global inequality, which had been falling but has now started to rise again after three decades ( Deaton, 2021 ; Ferreira, 2021 ).

Figure 1: Economic contraction in India and the world during Covid-19

Source: world economic outlook, international monetary fund, april 2021. note: the gross domestic product (gdp) per capita, constant prices is measured at purchase power parity; 2017 international dollars. the gdp per capita of each series is normalised to 100 in 2011. we use population-weighted average as the aggregation method., what do the main macroeconomic indicators tell us about india’s economy during the pandemic.

While economies worldwide have been hit hard, India has suffered one of the largest contractions. During the 2020/21 financial year, the rates of decline in GDP for the world were 3.3% and 2.2% for emerging market and developing economies. Table 1 summarises macroeconomic indicators for India, along with a reference group of comparable countries and the world. The fact that India’s growth rate in 2019 was among the highest makes the drop due to Covid-19 even more noticeable.

Comparing national unemployment rates in 2020, India’s rate of 7.1% indicates that it has performed relatively poorly – both in terms of the world average and compared with a set of reference group economies with similar per capita incomes. Unemployment rates were more muted within the reference group economies and were also kept low by generous labour market policies to keep people in work.

Despite the scale of the pandemic, additional budgetary allocation to various social safety measures has been relatively low in India compared with other countries. Although the country might look comparable to the reference group in non-health sector measures, the additional health sector fiscal measures are less than half those in the reference group. More worryingly, the Indian government's announced allocation in the 2021 budget for such measures does not show an increase, once inflation is taken into account.

Table 1: Summary of key macroeconomic indicators

Source: data on gross domestic product, constant prices (percentage change) is obtained from the world economic outlook database april 2021, international monetary fund . note: india’s gdp contraction is 8%, according to the international monetary fund (imf) and 7.3% from recent national estimates. unemployment rates (for youth, adults: 15+) are ilo-modelled estimates as of november 2021 and are obtained from ilostat, international labour organization (ilo) and world bank . fiscal measures are obtained from fiscal monitor database of country fiscal measures in response to the covid-19 pandemic as of april 2021, international monetary fund . the ‘reference group’ refers to the closest peer group statistic under which india falls. the reference group for gdp per capita is the emerging market and developing economies (emdes) classification by the imf. the reference group for the unemployment rate is the low- and middle-income countries (lmics) classification by the world bank. the reference group for the fiscal measures is the emdes classification by the imf. see ghatak and raghavan (forthcoming) for a comparison of india’s economic and health performance against the reference group., how has covid-19 changed income, consumption, poverty and unemployment in india.

While the macroeconomic statistics provide a snapshot of India’s economic position, they hide the large and unequal effects on households and workers within the country.

Both wealth and income inequality has been on the rise in India ( Ghatak, 2021 ). Estimates suggest that in 2020, the top 1% of the population held 42.5% of the total wealth, while the bottom 50% had only 2.5% of the total wealth ( Oxfam, 2020 ). Post-pandemic, the number of poor in India is projected to have more than doubled and the number of people in the middle class to have fallen by a third ( Kochhar, 2021 ).

During India’s first stringent national lockdown between April and May 2020, individual income dropped by approximately 40%. The bottom decile of households lost three months’ worth of income ( Azim Premji University, 2021 ; Beyer et al, 2021 ).

Microdata from the largest private survey in India, CMIE’s ‘Consumer Pyramids Household Survey’ (CPHS), show that per capita consumption spending dropped by more than GDP, and did not return to pre-lockdown levels during periods of reduced social distancing. Average per capita consumption spending continued to be over 20% lower after the first lockdown (in August 2020 compared with August 2019), and remained 15% lower year-on-year by the end of 2020.

Official poverty data are unavailable, and the CPHS data come with a caveat of ‘top’ and ‘bottom exclusions’. For example, official statistics show a rural headcount ratio of 35% in 2017/18 ( Subramanian, 2019 ). But the CPHS data estimate it at 25%, which suggests exclusions at the lower end of the consumption distribution ( Dreze and Somanchi, 2021 ).

Despite these statistical concerns, the CPHS does provide consumption numbers for a large sample of individuals, which can provide insights into changes in consumption levels arising from the pandemic.

Table 2 reports the percentage of people who have monthly consumption expenditure below different cut-off values. The different cut-offs encompass the official poverty lines (which, in any case, have been considered too low by some commentators). The current rural poverty line is set at 1,600 rupees (£15.50) per month or over, and the urban poverty line is 2,400 rupees per month (£23.37) or over.

Based on the latest CPHS data, rural poverty increased by 9.3 percentage points and urban poverty by over 11.7 percentage year-on-year from December 2019 to December 2020. Earlier months of the CPHS show that rural poverty increased by 14.2 percentage points and urban poverty by 18.1 percentage points. Yet the actual increase in poverty due to Covid-19 is likely to be higher than what the CPHS data suggest, as indicated by other surveys .

Table 2: Percentage of individuals by monthly consumption expenditure

Source: consumer pyramids household survey (cphs) for december 2019 and december 2020, and for august 2019 and august 2020. notes: estimates for consumption are calculated by dividing household adjusted total expenditure by household size and weighted using member level country weights. adjusted total expenditure is the sum total of all consumption goods and services purchased by the household during a month, adjusted using weekly records. real values are adjusted for inflation using the mospi cpi (iw) for urban workers and cpi (al) for rural workers (base 2012=100). headcount ratio is the percentage of individuals who are below the poverty line in urban and rural areas in each year. poverty line is the inflation-adjusted poverty line in rural areas (rs 972 in 2011-12 prices) and urban areas (rs 1410 in 2011-12 prices), which are adjusted to 2012 prices with the rbi cpi(al) and cpi(iw) for 2011/12-2012/13 respectively. all figures are in december 2019 values and observations with missing regions are dropped. despite a much larger sample in urban areas, the cphs also underestimates mean per capita consumption in urban areas, which is likely to reflect their inability to survey high-income urban households. from the draft national sample survey organisation (nsso) report on household consumer expenditure for 2017-18, the cphs estimate of mean per capita consumption in urban areas was 0.8 of the nsso level for 2017-18. for rural areas, the cphs estimate is 1.1 of the nsso level..

Taking into account the general trend of reduction in poverty, an estimated 230 million people in India have fallen into poverty as a result of the first wave of the pandemic ( Azim Premji University, 2021 ).

Table 3 shows that households in the middle of the pre-Covid-19 CPHS consumption distribution saw large drops in spending after the first wave of the pandemic, helping to create a new set of people entering poverty.

The percentage of poor people in the second lowest quintile of pre-Covid-19 consumption jumped from 32% to 60% within a year. This was driven largely by rural areas, where the headcount ratio for the second quintile almost doubled.

In urban areas, the poverty line is set higher due to greater living costs and 72% of people in the second quintile of the urban income distribution were below this poverty line before the pandemic. Within a year, they were joined in urban poverty by many who had higher incomes before. Half of people in the third quintile and 29% of people in the fourth quintile fell below the poverty line after the pandemic.

This sharp rise in poverty after the first lockdown is consistent with a variety of surveys that highlighted the depth of the crisis ( Azim Premji University, 2021 ). Year-on-year urban unemployment rate jumped from 8.8% in April to June 2019 to a staggering 20.8% in April to June 2020 ( Government of India National Statistical Office, 2020 ).

Table 3: Percentage of individuals who are below the poverty line in middle quintiles of pre-Covid-19 consumption expenditure, August 2019 to August 2020

Source: consumer pyramids household survey (cphs) for august 2019 and august 2020. notes: quintiles are based on 2019 mean per capita consumption levels for each region type. consumption levels are calculated by dividing household adjusted total expenditure by household size and weighted using member level country weights. adjusted total expenditure is the sum total of all consumption goods and services purchased by the household during a month, adjusted using weekly records. real values are adjusted for inflation using the mospi cpi (iw) for urban workers and cpi (al) for rural workers (base 2012=100). all figures are in december 2019 values and observations with missing regions are dropped..

The pandemic has brought severe economic hardship, especially to young individuals who are over-represented in informal work. India has a large share of young people in its workforce and the pandemic has put them at heightened risk of long-term unemployment. This has negative impacts on lifelong earnings and employment prospects ( Machin and Manning, 1999 ).

A study by the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP at the London School of Economics) analyses the depth of continuing joblessness among younger workers in the low-income states of Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh (see Table 4, Dhingra and Kondirolli, 2021 ).

The first round of the survey randomly sampled urban workers aged 18-40 during the first lockdown quarter, finding that a majority of them who had work before the pandemic were left with no work or no pay. After the first lockdown in April to June 2020, 20% of those sampled were out of work, another 9% were employed but had zero hours of work and 81% had no work or pay at all.

Ten months on from the first lockdown quarter, 8% of the sample continued to be out of work, another 8% were working zero hours, and 40% had no work or no pay. The rate of no work or no pay was higher (at 47%) among the youngest low-income individuals (those aged 18-25 who had below median pre-Covid-19 earnings).

Table 4: Crisis labour force status of individuals who were employed pre-Covid-19: recontact sample of individuals interviewed during the first lockdown (April to June 2020) and before the second wave (January to March 2021)

Source: cep-lse survey 2020 and 2021. note: out of work last week and zero hours last week are indicators for individuals who were unemployed in the week preceding the survey and employed but working zero hours in the week before the survey respectively. not paid is an indicator for individuals who received no pay in april 2020 in the column of april to june 2020 and those who received no pay during january to march 2021 in all other columns. median earnings are constructed using average earnings in january and february 2020. 18-25 refers to individuals who are between 18 to 25 years of age at the time of the first survey..

The recovery after the first wave was too muted to get many young Indian workers back into employment. For example, rural migrants continued to be reluctant to return to work in urban areas even before the second wave hit ( Imbert, 2021 ). And the second wave, which started in mid-February and appears to be flattening out in June 2021, heightened these risks of long-term unemployment by increasing the spells of economic inactivity.

What do public health indicators reveal about the impact of Covid-19 on India’s economy?

To avoid another livelihood crisis, India turned to local lockdowns during the second wave of the pandemic. Before the second wave, India’s public health performance (in terms of confirmed cases and confirmed deaths), while not the best, was ahead of several reference group countries. But the second wave has made India’s position significantly worse. The total confirmed cases per million now are comparable to those in the rest the world and the rate of vaccination is lower in India.

While death rates seem lower in India, there is massive underreporting. After accounting for the underreporting within official statistics, India’s total confirmed cases and deaths might exceed that of the rest of the world by a large margin (Gamio and Glanz, 2021).

In the conservative scenario, the total confirmed cases per million are about 13 times larger than in the rest of the world, and the total confirmed deaths per million are about 85% of that in the rest of the world. In the worst-case scenario, India is far behind the rest of the world.

There is an important caveat: while the focus of this article is on India, underreporting of Covid-19 cases and deaths is prevalent globally ( Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, 2021 ).

How has India fared so far?

More than a year has passed since India’s first national lockdown was announced. There was talk of a trade-off between lives and livelihoods when the Covid-19 crisis erupted last year. As India struggles in the second wave, it is clear that the country did poorly in both dimensions.

While India’s policy response was strong in terms of some aspects of lockdown stringency, it was ineffective in dealing with both the public health and economic aspects of the crisis. What’s more, it failed to limit the damaging impact of the crisis on the most vulnerable sections of the population.

Where can I find out more?

- State of working in India 2021 : Report from Azim Premji University’s Centre for Sustainable Employment on the effects of Covid-19 on jobs, incomes, inequality and poverty.

- City of dreams no more – The impact of Covid-19 on urban workers in India: Briefings from the Centre for Economic Performance.

- India needs a second wave of relief measures : Jean Drèze discusses the humanitarian and economic case for further support.

- Covid-19 articles from Debraj Ray .

- India COVID-19 chartbook : A series of charts on the effects of the pandemic in India from HSBC Global Research.

- India’s already-stressed rural economy is getting battered by the second wave of Covid-19 : Rohit Inani examines the crisis in India and calls for urgent relief measures.

Who are experts on this question?

- Amit Basole , Azim Premji University

- Swati Dhingra , LSE

- Maitreesh Ghatak , LSE

- Debraj Ray , New York University

- S. Subramanian , Independent Researcher

- Sanchari Roy , King's College London

Authors: Swati Dhingra and Maitreesh Ghatak

Swati thanks the erc for starting grant 760037. the authors would like to thank ramya raghavan and fjolla kondirolli for research assistance, photo by shubhangee vyas on unsplash.

- Swati Dhingra LSE View Profile

- Maitreesh Ghatak LSE View Profile

- News Ideas for the UK: election economics international week

- Prices & interest rates What are the future prospects for UK inflation?

- Trade & supply chains How is India’s trade landscape shaping up for the future?

Home — Essay Samples — Economics — Indian Economy — Impact Of Covid-19 On The Indian Economy

Impact of Covid-19 on The Indian Economy

- Categories: Covid 19 India Indian Economy

About this sample

Words: 1417 |

Published: Feb 8, 2022

Words: 1417 | Pages: 3 | 8 min read

Table of contents

Introduction.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_India

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341266520_Effect_of_COVID-19_on_the_Indian_Economy_and_Supply_Chain

- https://etinsights.et-edge.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/KPMG-REPORT-compressed.pdf

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health Geography & Travel Economics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 442 words

6 pages / 2505 words

1 pages / 426 words

1 pages / 664 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Indian Economy

Foreign investment refers to the investments made by the residents of a country in the financial assets and production process of another country. For example – an investor from USA invests in the equity stock of HDFC Bank (an [...]

The Indian financial system can be broadly classified into the formal (organized) financial system and the informal (unorganized) financial system. The formal financial system comes under the purview of the Ministry of [...]

Free trade and free trade with other nations allow businesses and markets to reach as many customers as possible, thus boosting sales, revenue, and potentially corporate profit. When sales are up it can lead to companies [...]

Conservative domination for the 13-year period between 1951 and 1964 is arguably largely a result of the economic prosperity which swept Europe throughout the same period, and equally managed to irradiate the need for a [...]

The focus of this paper is the international business and entrepreneurship. The paper is aimed at conducting a comparative analysis of the entrepreneurship in Europe and in the United States. The paper will assess various [...]

Tamils consider their language to be the "most pure" of the major Dravidian Languages (http://www.encyclopedia.com).Tamil is definitely not a popular language so I am going to share information about countries with Tamil [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

The Rise and Impact of COVID-19 in India

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Biosciences and Technology, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, India.

- 2 VIT-BS, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, India.

- PMID: 32574338

- PMCID: PMC7256162

- DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00250

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, which originated in the city of Wuhan, China, has quickly spread to various countries, with many cases having been reported worldwide. As of May 8th, 2020, in India, 56,342 positive cases have been reported. India, with a population of more than 1.34 billion-the second largest population in the world-will have difficulty in controlling the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 among its population. Multiple strategies would be highly necessary to handle the current outbreak; these include computational modeling, statistical tools, and quantitative analyses to control the spread as well as the rapid development of a new treatment. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of India has raised awareness about the recent outbreak and has taken necessary actions to control the spread of COVID-19. The central and state governments are taking several measures and formulating several wartime protocols to achieve this goal. Moreover, the Indian government implemented a 55-days lockdown throughout the country that started on March 25th, 2020, to reduce the transmission of the virus. This outbreak is inextricably linked to the economy of the nation, as it has dramatically impeded industrial sectors because people worldwide are currently cautious about engaging in business in the affected regions.

Keywords: COVID-19; India; SARS-CoV-2; economy; safety measures.

Copyright © 2020 Kumar, Kumar, Christopher and Doss.

India’s policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons for a post-COVID society

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 07 March 2024

- Volume 2 , article number 16 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Prakash Chand Kandpal 1

3929 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The COVID-19 pandemic has left an indelible mark on societies worldwide, challenging governments to respond swiftly and effectively to mitigate its impact. India, with its vast population and complex healthcare landscape, faced unique challenges in formulating and implementing a pandemic response strategy. The article examines India's policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic and explores the valuable lessons it offers for shaping a more resilient and prepared society in a post-COVID world. It provides a comprehensive analysis of India's multifaceted approach to managing the pandemic, highlighting key elements such as lockdowns, testing and contact tracing, healthcare infrastructure, vaccination drives, and economic relief measures. By delving into both the successes and shortcomings of these policies, it seeks to extract valuable insights for policymakers and public health officials globally. As the world transitions into a post-COVID era, the lessons learned from India's experience offer a roadmap for building stronger healthcare systems, improving disaster preparedness, and enhancing social safety nets. The article underscores the importance of proactive governance, community engagement, data-driven decision-making, and international collaboration in the face of global health crises. The paper demonstrates that India's journey through the pandemic provides a wealth of knowledge that can inform policy development, foster greater resilience, and help societies better navigate the uncertainties of a post-COVID world. By reflecting on the successes and challenges of India's response, this article offers actionable insights for shaping a more equitable, sustainable, and prepared society in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

All-Hands-On-Deck!—How International Organisations Respond to the COVID-19 Pandemic

The Long 2020/21 in India: Models of Pandemic Management and Logistics of Governance

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

India, a large country of about 1.3 billion people, witnessed its first Coronavirus case on 30th January 2020, in Kerala, in a student returning from Wuhan [ 1 ]. It was on the same day that the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern [ 2 ]. However, it was not until March 2020 that the country realized the intensity of the virus. The government took notice of how the virus became a global concern in no time, so much so that it was declared to be a pandemic on March 11, 2020, in just little over three months when the first human case was identified in Wuhan, People’s Republic of China. The Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare acknowledged the respiratory disorder that originated in China as highly dangerous and immediately called the Joint Monitoring Group to keep a close eye on further developments. Taking swift action on the issue, the Government of India constituted 11 Empowered Groups on 29 March to investigate the different aspects of COVID-19 management and to assess the risk, review the preparedness and response mechanisms, finalize technical guidelines, and make informed decisions in time on them. Like the rest of the world, India followed suit and announced a complete lockdown on March 24, 2020. By 12th March 2020, India had reported more than 500 cases across various states such as Delhi, Rajasthan, and Telangana, and the initial death count was 10 [ 3 ].

1.1 Impact of Covid pandemic

COVID-19 affected the everyday life of humans and hindered the worldwide economy. The pandemic also impacted a social life of people all over the world. The infection spread all over the globe, almost in 213 countries as per WHO reports, and has shown severe implications for countries' economic and health systems [ 4 , 5 ]. The pandemic shook the roots of world systems and states at almost all levels. The “abnormal” way of life became “normal,” and people were compelled to survive amidst a nationwide lockdown. At times like these, it was the spirit of mankind that helped people fight all odds and go through tough times. The worldwide outbreak of Coronavirus buckled the public health system. Countries across the world struggled to contain the fast spread of the virus as it continued to have a devastating impact on the lives of the people.

The economic devastation caused by the pandemic was very prevalent and easy to monitor. However, it was the ‘disguised disruption’ of structural units that caused the real damage. From shops to schools and offices to public places, a shutdown of everything caused people to directly bear the socio-economic and emotional costs of the pandemic. This caused a massive migrant and labor crisis, with everyone desperately searching for asylum. The 454 million internal migrants felt desperate to return to the safe havens of their homes, also because the means of their livelihood at their place of work was now shut down due to the pandemic [ 6 ].

With the closure of educational institutions to contain the spread of the contagious virus, the burden shifted to the students who were enrolled in schools and colleges or coaching classes. The fee, when coupled with the cut down on family income, caused a heavy dropout, especially for the girl child, who is always the easiest target and the most burnt bearer of a tragedy [ 7 ]. The share of the unorganized sector, which was most hit by the closure and the lockdown, in employment is around 83%. This was going to have a long-term impact on the Indian economy—as while the organised sector switched to continue its business as usual through online mode, work-from-home structure, and technological support; the unorganized sector came to a virtual standstill. The state's healthcare sector, too, shifted the entire “guns and butter” equation to just one unit, and the other regular check-ups, immunization programs, and any other aspect of healthcare program or concern took a back seat—putting the elderly and the diseased at great risk. Put together, the pandemic was a mammoth challenge for everyone, from people to institutions, societies to states. However, it was the collective will, timely-made policies, India’s social capital, and quick responses that helped the country sail through the adversaries.

1.2 Response of the Indian State

As a global response to the pandemic and to contain the spread of the virus, various Public and Private institutions switched to online modes of functioning, such as schools, colleges, and even the Judiciary. But this facility was not available to all sectors and institutions as many other organizations continued to work on the ground, such as those serving essential commodities, medical industries, agricultural sector, transport industry, and the civil society actors—who together came forward towards smooth functioning of the society and economy during the crisis period. In India, various policy reform measures were adopted across various sectors, such as education, health, economy, agriculture, and health, to keep the life of the country functional and the economy afloat. The following section deals with this aspect in detail.

1.3 Education sector

Education has long been a crucial component in assessing development trends throughout time and across countries. It has proved instrumental in numerous ways, from reducing poverty and inequality to preparing the path for long-term economic prosperity. Higher pay, social mobility, practical life skills, increased discipline, and a readiness to change have all been advantages of education.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, India’s poor educational records have been exacerbated, with schools being closed since March 2020. Schools in India had to be closed for the largest number of weeks. Since the March 2020 lockdown, 1.5 million schools have been closed, and 247 million primary and secondary pupils have been dropped out of school [ 8 ]. Schools have been attempting to replace in-person classes with online learning since most primary school students have not attended school in over a year. Teachers and institutions have experimented with using e-platforms like WhatsApp groups, group tutoring, Zoom, and Skype to reach out to their students. Other creative approaches to reaching them include using loudspeaker tutorials for those without an internet connection. The internet connectivity and the digital divide in Indian society were laid clear, with people even climbing over trees and buildings to get signals.

These online lessons, however, have had a mixed response. While many children in metropolitan regions have accessed online classes, many preferred lectures "in a classroom," where they would not be forced to "do everything on WhatsApp—i.e., submit assignments, talk to friends, ask questions." Many students take online classes for more than four lessons every day, including core subjects like English and Science, as well as extracurricular activities like dance or taekwondo [ 9 ]. As a result, students started spending a significant amount of time on their laptops or mobile devices. Parents who disliked technology and digital exposure, on the other hand, objected to online classes because "they complained about their children's increased screen time." Due to the extended lockout and the necessity to do other domestic duties, some parents found it difficult to assist their children with the online learning paradigm [ 10 ]. Teachers also expressed dissatisfaction with their inability to establish "rapport with the youngsters," as they did in school. They believed that because teachers got little chance to interact online, they were unable to monitor "body language in class," and "their connection with peers” was affected. As a result, many teachers claimed that remote learning made it harder to engage students [ 11 ].

However, due to poor connectivity and lack of access to digital devices, many students, particularly in rural regions, face many problems in accessing online learning material. According to a report on India's Key Indicators of Household Social Consumption on Education, only 15% of rural families had access to the Internet, compared to 42% of urban households [ 12 ]. Many students struggled because they lacked personal gadgets or one designated for studies, had poor internet connections, or simply couldn't afford an internet connection. The schools, too, failed to provide the necessary infrastructure to the teachers and the students to take up the task of online education. A sudden shift was destined to have problems on both ends as teachers were not trained on how to teach in an online mode, and the students couldn't grasp what was being taught. This made them helpless.

Many families experienced financial hardship as a result of the pandemic, which was going to have an impact on other aspects of their livelihood. During school closures, some of the poorest families couldn’t even afford a digital gadget to avail their children of access to education or other skill training. This created a learning divide, which shall have an impact in the long run. The lengthy closure of schools had been a burden, and over 90% of low-income parents wanted schools to return as soon as feasible [ 13 ]. The reopening of schools, on the other hand, had ebbed and flowed. The Union government allowed schools to begin on October 15, 2020, but gave the respective state education boards to decide the course of action, which was to be based on the incidence of COVID-19 infections in the area and the regular COVID guidelines issued by the Health ministry. The reopening program that was suggested contained options of alternate day schooling, two-day schooling, and continuous use of online learning, as well as two school shifts per day, staggered timetables, and outdoor sessions [ 14 ]. The elderly and the children were the most vulnerable, and the government could not have afforded a fresh spread of the virus, especially when signs of its mutations were evident. The experiences from other countries also helped India to learn the way out.

After the announcement in October 2020, certain states, like Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, and Uttarakhand, reopened their schools but had to close them because numerous people (students, teachers, and school staff) got infected. Due to the forthcoming board exams, schools in Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Odisha, and Karnataka were to reopen in February 2021, notably for those in grades 9–12 [ 14 ]. However, with India's second wave of COVID-19 infections in March 2021, the number of cases increased once more. As a result, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Delhi, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu chose to close primary schools. The second wave was the most fatal and pushed state healthcare machinery to its maximum, and the number of infected people, along with those who died due to it, broke all records. India overnight became a global hotspot of COVID-19 [ 15 ]. However, several schools across India began to reopen at the beginning of September 2021 after being closed for 18 months. Many cautious precautions were implemented for this reopening, including "stay-at-home" advice, "50 percent capacity, thermal screening, physically distanced seating arrangements, among others." Many schools also improved their infrastructure, such as ventilation, water supply, and restrooms, to support efforts of containment of the virus and restrict its spread. However, the long-term effects of the school shutdown still need more assessment.

The lack of communication between different stakeholders also created confusion sometimes regarding the guidelines, but the teaching–learning experience was sure to have taken a long-term hit with the uncertainty over the upcoming times as the virus was not mutating and taking different forms, resisting the effect of the vaccine. The effect of this can be largely felt in the rural areas. A prolonged disconnect from the studies pushed them way back from where they were. They were unable to recall vernacular scripts and lessons that they had been taught thus far. Thus taking it all to square one or even more primordial. The 18-month school shutdown stunted the development of educational faculties. In addition to the lost knowledge and know-how, the distress could be seen in the rate of dropouts. In rural areas or families with low income, education is seen as a trade-off. It is seen as if the family is compromising on an earning hand by sending their child to school based on a promise of a brighter future. With the onset of the pandemic, people lost their jobs, and this directly compelled them to let go of the education their child was attaining at different levels. These large chunks of dropouts put together would change the dynamics of an entire generation if left unattended at this crucial juncture.

Furthermore, these dropouts would reinforce gender stereotypes and widen the gap [ 16 ]. Girls were an obvious choice to cut resources in times of crisis, and they would be then married off at an early age to reduce their dependency on the family. Therefore, this would strengthen the gender education gap and give rise to child marriages and child labor, both of which are heinous crimes but extremely prevalent in India, particularly amongst the rural poor. In the urban setups, though the girls are not forced to drop out of school, their education remains burdensome. They were expected to fit in the “gender roles'' and help with household chores, which adds to the overall workload. This, in turn, caused them to neglect their studies and overall well-being [ 17 ].

Apart from the gender gap troubles and related adversaries, the shutdown of schools has had an even deeper impact on the overall well-being and health structure of the country. The Midday Meal Scheme was a win–win policy that the government had in place, as it hit two birds with a single stone. On the one hand, it was able to increase the attendance rate and provide education to a good sum of people, while on the other hand, it was able to provide nutritious food to the children that would help forestall stunting, early deaths, and mal-nutrition amongst other food-related illnesses. The meal provided children with daily bodily requirements of proteins and nutrition. However, a shutdown came haunting their health at a time when they should have the best of it to maintain their immunity against the virus [ 18 ].

The nutrition intake scheme was not a yearly process or a short-term goal. It was to help a child develop into a healthy adult while making use of its potential and capabilities. However, a cut on this has risked their future stakes of becoming a healthy, productive, and sound individual who would have the freedom to explore the best of his/her capabilities and contribute to the progress of society. This prominent aspect of human capital formation faced serious risk and, if not corrected within the given time frame, would affect the health of the younger lot, which would define the coming generation and, therefore, the state’s capabilities in the long run [ 14 ]. Moreover, malnutrition in children makes them susceptible to regular diseases and weakness, which makes them skip school, and if left untreated, they could become chronic in nature. All of this led to an increase in the pressure on the state's healthcare system. The state’s increased spending on healthcare came from a cut down on spending on developmental projects. Therefore, both the state and society suffered and started drifting on the path of regression and not progress [ 19 ].

To tackle the situation, the Central government and many state governments ordered Anganwadis and schools to supply midday meals either in raw form or cooked form to all the students. Moreover, some states attempted to regulate this supply using ration cards or cash transfers to the families. Nevertheless, due to the structural factors and loopholes in the systems clubbed with red-tapism and corruption, not everyone could receive these packages or help [ 20 ]. The Midday Meal Scheme might be the same, but the way it has been implemented during the lockdown differed at the state level. While states like Haryana and Chhattisgarh preferred giving dry rations, Telangana provided hot cooked food, while in Bihar, cash transfer was preferred. These implementation level differences were reflected in the results, and the benefits could not reach all [ 21 ].

In addition to this, the shutdown had layers of intersecting factors of caste, class, and religion to it. The upward mobility was snapped for people belonging to lower caste and class. People from Schedule Castes and Tribes who were making a living out of their traditional skills in the city had to move back to the more primitive and highly stereotyped societies, i.e., to their villages, and had to suffer the discrimination which they had earlier fled from. This made the situation far worse [ 22 ]. The tragedy of suffering did not end here. The pandemic affected the mental well-being of poor families who were running on a hand-to-mouth basis, and this sudden economic jolt added to their grievances. Studies establish that the decline in economic status triggered mental ill health problems during the pandemic situation. It has been observed that, although most people had adjusted to COVID-19, levels of anxiety, depression, and stress remained high for respondents who experienced a deterioration in income. The studies also confirm that anxiety, depression, and stress levels were high for economically vulnerable sections of the population [ 23 , 24 ] particularly in developing countries [ 25 , 26 , 27 ].

The mental health of the children suffered a lot. There were many news of them committing suicide following despair or pressure of not being able to do something. In urban households, loneliness caused stress and anxiety in the children, and the lack of communication in the modern family added to the distress. Children who were not able to get therapy or communicate their emotions got caught in a sea of endless thoughts. This attack on their mental health has been overlooked in the state policies. Suicide was the leading cause for over 300 “non-coronavirus deaths” reported in India due to distress triggered by the nationwide lockdown, revealed a new set of data compiled by a group of researchers. The group, comprising public interest technologist Thejesh GN, activist Kanika Sharma, and assistant professor of legal practice at Jindal Global School of Law Aman, said 338 deaths have occurred from March 19 till May 2 and they are related to lockdown. According to the data, 80 people killed themselves due to loneliness and fear of being tested positive for the virus. The suicides are followed by migrants dying in accidents on their way back home (51), deaths associated with withdrawal symptoms (45), and those related to starvation and financial distress (36) [ 28 ].

A lot of things could work because of the strong civil society presence that India has had. Non-governmental organizations, foundations, unions, and individuals from all walks of life came together in these tough times to address the needs of children in their personal capacities. Schools and colleges quickly moved online to keep things going as “usual” to create a psychological impression of normal times. Furthermore, organizations helped deliver books, mobiles, and internet connection facilities in rural areas to keep everyone connected. On the academic front, teachers and professors volunteered to teach their peers in the virtual mode of learning and teaching. This helped develop a community where everyone was keen to learn the new ways of teaching and provide lectures. This bandwagon was joined by coaching institutes and tutors who dispatched tabs in remote areas to facilitate the learning mechanism. A blessing in disguise was the language. Since India has a fairly good amount of English Speakers or people who can read and write in English, or at least know the bare minimum of it, they were able to adapt to the online mode quickly. Even the technology was quick to adapt to people’s needs, and many major tech providers introduced regional languages in their applications to help users connect in a dire situation like the Pandemic. This two-front war and timely action and support from all ends helped the boat from sinking up to a great extent. However, there still lies plenty of scope for improvement and accommodation. The government has been trying to make ends meet and bring children back to school, but it would need to work closely on all the related aspects to make things “normal.”

1.4 Health sector