Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- A Quick Guide to Experimental Design | 5 Steps & Examples

A Quick Guide to Experimental Design | 5 Steps & Examples

Published on 11 April 2022 by Rebecca Bevans . Revised on 5 December 2022.

Experiments are used to study causal relationships . You manipulate one or more independent variables and measure their effect on one or more dependent variables.

Experimental design means creating a set of procedures to systematically test a hypothesis . A good experimental design requires a strong understanding of the system you are studying.

There are five key steps in designing an experiment:

- Consider your variables and how they are related

- Write a specific, testable hypothesis

- Design experimental treatments to manipulate your independent variable

- Assign subjects to groups, either between-subjects or within-subjects

- Plan how you will measure your dependent variable

For valid conclusions, you also need to select a representative sample and control any extraneous variables that might influence your results. If if random assignment of participants to control and treatment groups is impossible, unethical, or highly difficult, consider an observational study instead.

Table of contents

Step 1: define your variables, step 2: write your hypothesis, step 3: design your experimental treatments, step 4: assign your subjects to treatment groups, step 5: measure your dependent variable, frequently asked questions about experimental design.

You should begin with a specific research question . We will work with two research question examples, one from health sciences and one from ecology:

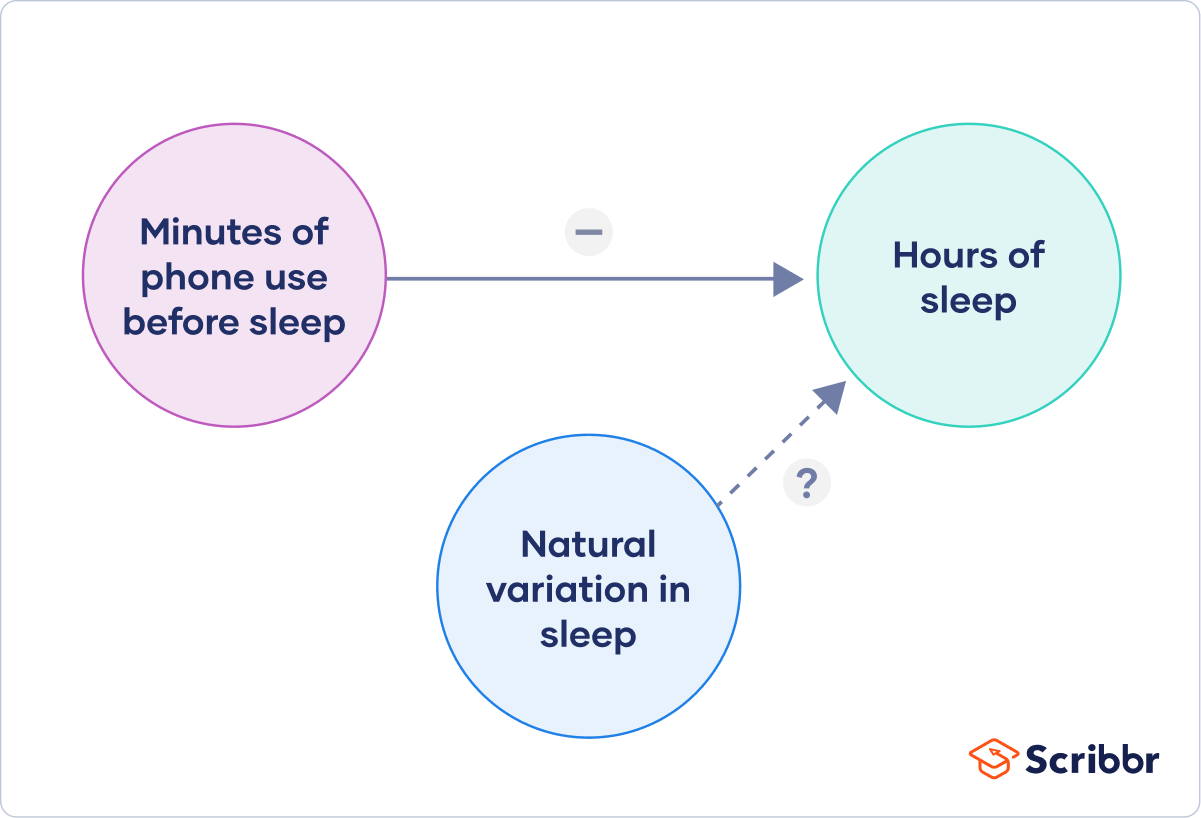

To translate your research question into an experimental hypothesis, you need to define the main variables and make predictions about how they are related.

Start by simply listing the independent and dependent variables .

Then you need to think about possible extraneous and confounding variables and consider how you might control them in your experiment.

Finally, you can put these variables together into a diagram. Use arrows to show the possible relationships between variables and include signs to show the expected direction of the relationships.

Here we predict that increasing temperature will increase soil respiration and decrease soil moisture, while decreasing soil moisture will lead to decreased soil respiration.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Now that you have a strong conceptual understanding of the system you are studying, you should be able to write a specific, testable hypothesis that addresses your research question.

The next steps will describe how to design a controlled experiment . In a controlled experiment, you must be able to:

- Systematically and precisely manipulate the independent variable(s).

- Precisely measure the dependent variable(s).

- Control any potential confounding variables.

If your study system doesn’t match these criteria, there are other types of research you can use to answer your research question.

How you manipulate the independent variable can affect the experiment’s external validity – that is, the extent to which the results can be generalised and applied to the broader world.

First, you may need to decide how widely to vary your independent variable.

- just slightly above the natural range for your study region.

- over a wider range of temperatures to mimic future warming.

- over an extreme range that is beyond any possible natural variation.

Second, you may need to choose how finely to vary your independent variable. Sometimes this choice is made for you by your experimental system, but often you will need to decide, and this will affect how much you can infer from your results.

- a categorical variable : either as binary (yes/no) or as levels of a factor (no phone use, low phone use, high phone use).

- a continuous variable (minutes of phone use measured every night).

How you apply your experimental treatments to your test subjects is crucial for obtaining valid and reliable results.

First, you need to consider the study size : how many individuals will be included in the experiment? In general, the more subjects you include, the greater your experiment’s statistical power , which determines how much confidence you can have in your results.

Then you need to randomly assign your subjects to treatment groups . Each group receives a different level of the treatment (e.g. no phone use, low phone use, high phone use).

You should also include a control group , which receives no treatment. The control group tells us what would have happened to your test subjects without any experimental intervention.

When assigning your subjects to groups, there are two main choices you need to make:

- A completely randomised design vs a randomised block design .

- A between-subjects design vs a within-subjects design .

Randomisation

An experiment can be completely randomised or randomised within blocks (aka strata):

- In a completely randomised design , every subject is assigned to a treatment group at random.

- In a randomised block design (aka stratified random design), subjects are first grouped according to a characteristic they share, and then randomly assigned to treatments within those groups.

Sometimes randomisation isn’t practical or ethical , so researchers create partially-random or even non-random designs. An experimental design where treatments aren’t randomly assigned is called a quasi-experimental design .

Between-subjects vs within-subjects

In a between-subjects design (also known as an independent measures design or classic ANOVA design), individuals receive only one of the possible levels of an experimental treatment.

In medical or social research, you might also use matched pairs within your between-subjects design to make sure that each treatment group contains the same variety of test subjects in the same proportions.

In a within-subjects design (also known as a repeated measures design), every individual receives each of the experimental treatments consecutively, and their responses to each treatment are measured.

Within-subjects or repeated measures can also refer to an experimental design where an effect emerges over time, and individual responses are measured over time in order to measure this effect as it emerges.

Counterbalancing (randomising or reversing the order of treatments among subjects) is often used in within-subjects designs to ensure that the order of treatment application doesn’t influence the results of the experiment.

Finally, you need to decide how you’ll collect data on your dependent variable outcomes. You should aim for reliable and valid measurements that minimise bias or error.

Some variables, like temperature, can be objectively measured with scientific instruments. Others may need to be operationalised to turn them into measurable observations.

- Ask participants to record what time they go to sleep and get up each day.

- Ask participants to wear a sleep tracker.

How precisely you measure your dependent variable also affects the kinds of statistical analysis you can use on your data.

Experiments are always context-dependent, and a good experimental design will take into account all of the unique considerations of your study system to produce information that is both valid and relevant to your research question.

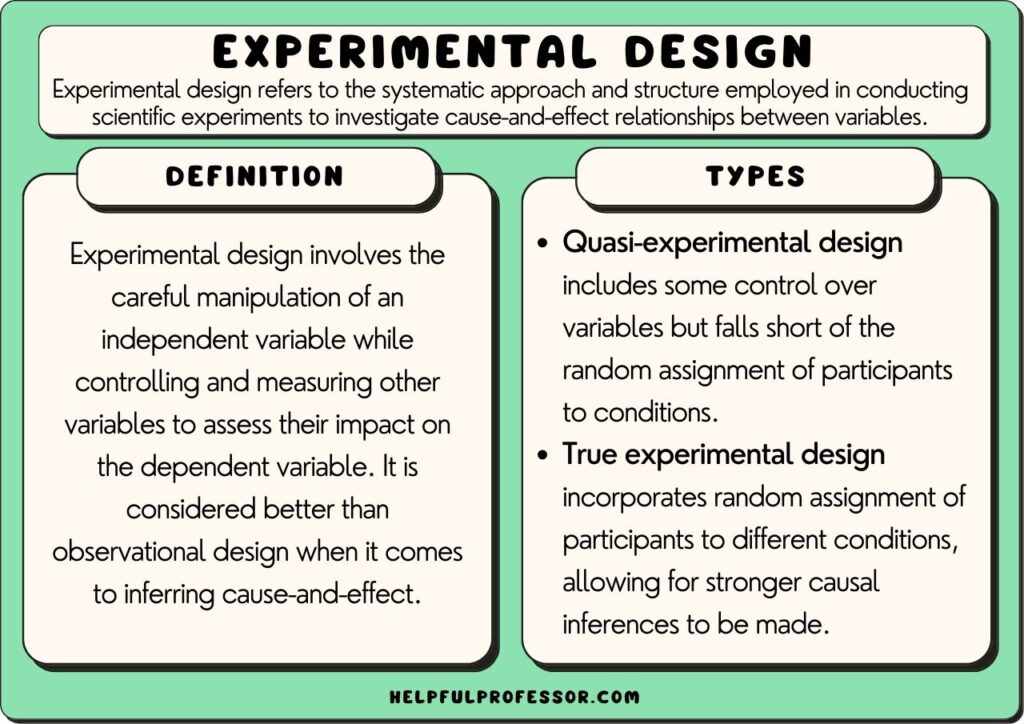

Experimental designs are a set of procedures that you plan in order to examine the relationship between variables that interest you.

To design a successful experiment, first identify:

- A testable hypothesis

- One or more independent variables that you will manipulate

- One or more dependent variables that you will measure

When designing the experiment, first decide:

- How your variable(s) will be manipulated

- How you will control for any potential confounding or lurking variables

- How many subjects you will include

- How you will assign treatments to your subjects

The key difference between observational studies and experiments is that, done correctly, an observational study will never influence the responses or behaviours of participants. Experimental designs will have a treatment condition applied to at least a portion of participants.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

In a between-subjects design , every participant experiences only one condition, and researchers assess group differences between participants in various conditions.

In a within-subjects design , each participant experiences all conditions, and researchers test the same participants repeatedly for differences between conditions.

The word ‘between’ means that you’re comparing different conditions between groups, while the word ‘within’ means you’re comparing different conditions within the same group.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bevans, R. (2022, December 05). A Quick Guide to Experimental Design | 5 Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 11 November 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/guide-to-experimental-design/

Is this article helpful?

Rebecca Bevans

15 Experimental Design Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Experimental design involves testing an independent variable against a dependent variable. It is a central feature of the scientific method .

A simple example of an experimental design is a clinical trial, where research participants are placed into control and treatment groups in order to determine the degree to which an intervention in the treatment group is effective.

There are three categories of experimental design . They are:

- Pre-Experimental Design: Testing the effects of the independent variable on a single participant or a small group of participants (e.g. a case study).

- Quasi-Experimental Design: Testing the effects of the independent variable on a group of participants who aren’t randomly assigned to treatment and control groups (e.g. purposive sampling).

- True Experimental Design: Testing the effects of the independent variable on a group of participants who are randomly assigned to treatment and control groups in order to infer causality (e.g. clinical trials).

A good research student can look at a design’s methodology and correctly categorize it. Below are some typical examples of experimental designs, with their type indicated.

Experimental Design Examples

The following are examples of experimental design (with their type indicated).

1. Action Research in the Classroom

Type: Pre-Experimental Design

A teacher wants to know if a small group activity will help students learn how to conduct a survey. So, they test the activity out on a few of their classes and make careful observations regarding the outcome.

The teacher might observe that the students respond well to the activity and seem to be learning the material quickly.

However, because there was no comparison group of students that learned how to do a survey with a different methodology, the teacher cannot be certain that the activity is actually the best method for teaching that subject.

2. Study on the Impact of an Advertisement

An advertising firm has assigned two of their best staff to develop a quirky ad about eating a brand’s new breakfast product.

The team puts together an unusual skit that involves characters enjoying the breakfast while engaged in silly gestures and zany background music. The ad agency doesn’t want to spend a great deal of money on the ad just yet, so the commercial is shot with a low budget. The firm then shows the ad to a small group of people just to see their reactions.

Afterwards they determine that the ad had a strong impact on viewers so they move forward with a much larger budget.

3. Case Study

A medical doctor has a hunch that an old treatment regimen might be effective in treating a rare illness.

The treatment has never been used in this manner before. So, the doctor applies the treatment to two of their patients with the illness. After several weeks, the results seem to indicate that the treatment is not causing any change in the illness. The doctor concludes that there is no need to continue the treatment or conduct a larger study with a control condition.

4. Fertilizer and Plant Growth Study

An agricultural farmer is exploring different combinations of nutrients on plant growth, so she does a small experiment.

Instead of spending a lot of time and money applying the different mixes to acres of land and waiting several months to see the results, she decides to apply the fertilizer to some small plants in the lab.

After several weeks, it appears that the plants are responding well. They are growing rapidly and producing dense branching. She shows the plants to her colleagues and they all agree that further testing is needed under better controlled conditions .

5. Mood States Study

A team of psychologists is interested in studying how mood affects altruistic behavior. They are undecided however, on how to put the research participants in a bad mood, so they try a few pilot studies out.

They try one suggestion and make a 3-minute video that shows sad scenes from famous heart-wrenching movies.

They then recruit a few people to watch the clips and measure their mood states afterwards.

The results indicate that people were put in a negative mood, but since there was no control group, the researchers cannot be 100% confident in the clip’s effectiveness.

6. Math Games and Learning Study

Type: Quasi-Experimental Design

Two teachers have developed a set of math games that they think will make learning math more enjoyable for their students. They decide to test out the games on their classes.

So, for two weeks, one teacher has all of her students play the math games. The other teacher uses the standard teaching techniques. At the end of the two weeks, all students take the same math test. The results indicate that students that played the math games did better on the test.

Although the teachers would like to say the games were the cause of the improved performance, they cannot be 100% sure because the study lacked random assignment . There are many other differences between the groups that played the games and those that did not.

Learn More: Random Assignment Examples

7. Economic Impact of Policy

An economic policy institute has decided to test the effectiveness of a new policy on the development of small business. The institute identifies two cities in a third-world country for testing.

The two cities are similar in terms of size, economic output, and other characteristics. The city in which the new policy was implemented showed a much higher growth of small businesses than the other city.

Although the two cities were similar in many ways, the researchers must be cautious in their conclusions. There may exist other differences between the two cities that effected small business growth other than the policy.

8. Parenting Styles and Academic Performance

Psychologists want to understand how parenting style affects children’s academic performance.

So, they identify a large group of parents that have one of four parenting styles: authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, or neglectful. The researchers then compare the grades of each group and discover that children raised with the authoritative parenting style had better grades than the other three groups. Although these results may seem convincing, it turns out that parents that use the authoritative parenting style also have higher SES class and can afford to provide their children with more intellectually enriching activities like summer STEAM camps.

9. Movies and Donations Study

Will the type of movie a person watches affect the likelihood that they donate to a charitable cause? To answer this question, a researcher decides to solicit donations at the exit point of a large theatre.

He chooses to study two types of movies: action-hero and murder mystery. After collecting donations for one month, he tallies the results. Patrons that watched the action-hero movie donated more than those that watched the murder mystery. Can you think of why these results could be due to something other than the movie?

10. Gender and Mindfulness Apps Study

Researchers decide to conduct a study on whether men or women benefit from mindfulness the most. So, they recruit office workers in large corporations at all levels of management.

Then, they divide the research sample up into males and females and ask the participants to use a mindfulness app once each day for at least 15 minutes.

At the end of three weeks, the researchers give all the participants a questionnaire that measures stress and also take swabs from their saliva to measure stress hormones.

The results indicate the women responded much better to the apps than males and showed lower stress levels on both measures.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to conclude that women respond to apps better than men because the researchers could not randomly assign participants to gender. This means that there may be extraneous variables that are causing the results.

11. Eyewitness Testimony Study

Type: True Experimental Design

To study the how leading questions on the memories of eyewitnesses leads to retroactive inference , Loftus and Palmer (1974) conducted a simple experiment consistent with true experimental design.

Research participants all watched the same short video of two cars having an accident. Each were randomly assigned to be asked either one of two versions of a question regarding the accident.

Half of the participants were asked the question “How fast were the two cars going when they smashed into each other?” and the other half were asked “How fast were the two cars going when they contacted each other?”

Participants’ estimates were affected by the wording of the question. Participants that responded to the question with the word “smashed” gave much higher estimates than participants that responded to the word “contacted.”

12. Sports Nutrition Bars Study

A company wants to test the effects of their sports nutrition bars. So, they recruited students on a college campus to participate in their study. The students were randomly assigned to either the treatment condition or control condition.

Participants in the treatment condition ate two nutrition bars. Participants in the control condition ate two similar looking bars that tasted nearly identical, but offered no nutritional value.

One hour after consuming the bars, participants ran on a treadmill at a moderate pace for 15 minutes. The researchers recorded their speed, breathing rates, and level of exhaustion.

The results indicated that participants that ate the nutrition bars ran faster, breathed more easily, and reported feeling less exhausted than participants that ate the non-nutritious bar.

13. Clinical Trials

Medical researchers often use true experiments to assess the effectiveness of various treatment regimens. For a simplified example: people from the population are randomly selected to participate in a study on the effects of a medication on heart disease.

Participants are randomly assigned to either receive the medication or nothing at all. Three months later, all participants are contacted and they are given a full battery of heart disease tests.

The results indicate that participants that received the medication had significantly lower levels of heart disease than participants that received no medication.

14. Leadership Training Study

A large corporation wants to improve the leadership skills of its mid-level managers. The HR department has developed two programs, one online and the other in-person in small classes.

HR randomly selects 120 employees to participate and then randomly assigned them to one of three conditions: one-third are assigned to the online program, one-third to the in-class version, and one-third are put on a waiting list.

The training lasts for 6 weeks and 4 months later, supervisors of the participants are asked to rate their staff in terms of leadership potential. The supervisors were not informed about which of their staff participated in the program.

The results indicated that the in-person participants received the highest ratings from their supervisors. The online class participants came in second, followed by those on the waiting list.

15. Reading Comprehension and Lighting Study

Different wavelengths of light may affect cognitive processing. To put this hypothesis to the test, a researcher randomly assigned students on a college campus to read a history chapter in one of three lighting conditions: natural sunlight, artificial yellow light, and standard fluorescent light.

At the end of the chapter all students took the same exam. The researcher then compared the scores on the exam for students in each condition. The results revealed that natural sunlight produced the best test scores, followed by yellow light and fluorescent light.

Therefore, the researcher concludes that natural sunlight improves reading comprehension.

See Also: Experimental Study vs Observational Study

Experimental design is a central feature of scientific research. When done using true experimental design, causality can be infered, which allows researchers to provide proof that an independent variable affects a dependent variable. This is necessary in just about every field of research, and especially in medical sciences.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *