- Psychology , Psychology Experiments

Cognitive Dissonance: Always Believe in What You Do

Have You Ever?

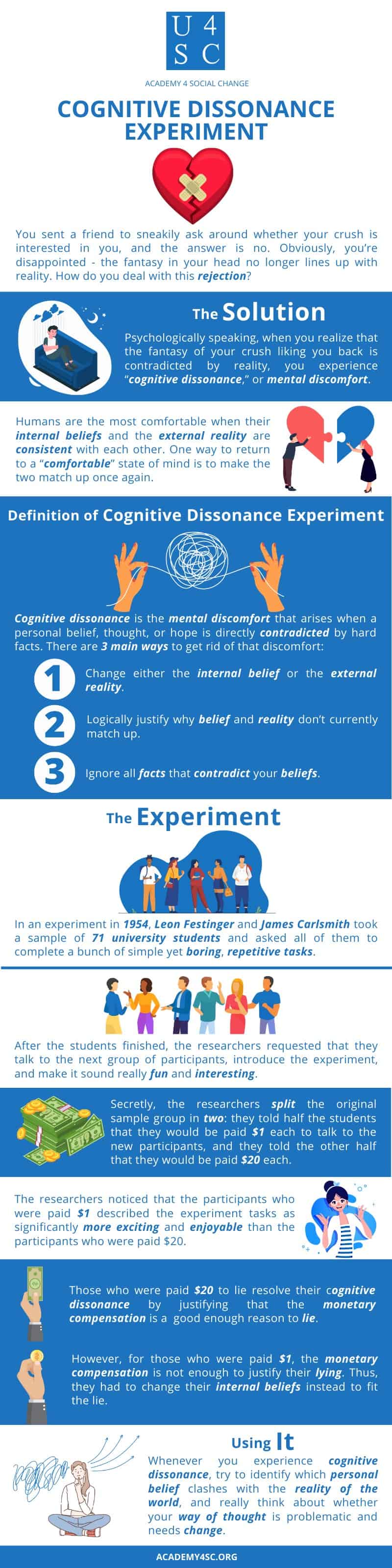

When you have a crush on someone, you typically hope that this person likes you back and that you’ll eventually end up dating. Let’s say that you sent a friend to sneakily ask around whether your crush is interested in you as well, and the answer is no . Obviously, you’re disappointed - the fantasy in your head no longer lines up with reality. How do you deal with this rejection?

Psychologically speaking, when you realize that the fantasy of your crush liking you back is contradicted by reality, you experience “cognitive dissonance,” or mental discomfort. Humans are the most comfortable when their internal beliefs and the external reality of the world are consistent with each other. One way to return to a “comfortable” state of mind is to change either the internal belief or the external reality so that the two match up once again. In this case, you need to either convince yourself that you never had feelings for your crush in the first place, or you somehow brew up a love potion for your crush so that they’ll ask you out.

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort that arises when a personal belief, thought, or hope is directly contradicted by hard facts. There are 3 main ways to get rid of that discomfort: 1) change either the internal belief or the external reality, 2) logically justify why belief and reality don’t currently match up, and 3) ignore all facts that contradict your beliefs.

A famous experiment was conducted by Leon Festinger and James Carlsmith in 1954 that brought cognitive dissonance to the attention of all psychologists. In this experiment, Festinger and Carlsmith took a sample of 71 university students and asked all of them to complete a bunch of simple yet boring, repetitive tasks. After the students finished, the researchers requested that they talk to the next group of participants, introduce the experiment, and make it sound really fun and interesting. Secretly, the researchers split the original sample group in two: they told half the students that they would be paid $1 each to talk to the new participants, and they told the other half that they would be paid $20 each. Almost all the original participants agreed to do the job. However, the researchers noticed that the participants who were paid $1 described the experiment tasks as significantly more exciting and enjoyable than the participants who were paid $20.

What’s the reason for this difference? Well, all the original participants in the experiment thought that the experiment tasks were boring, and since lying about the tasks being fun directly opposes their beliefs, this action would activate their cognitive dissonance. Those who were paid $20 to lie resolve their cognitive dissonance by justifying that the monetary compensation is a good enough reason to lie. However, for those who were paid $1, the monetary compensation is not enough to justify their lying. Thus, to solve their cognitive dissonance, they had to change their internal beliefs instead to fit the lie: they made themselves believe that the experiment was actually really fun, and thus, their “lies” were especially enthusiastic.

Applying It

Cognitive dissonance is helpful because it alerts you when your beliefs don’t line up with the actions you take in reality. However, the way in which you choose to resolve that mental discomfort can be potentially harmful to yourself or others around you. For instance, many people experience cognitive dissonance when indulging in addictive behaviors like smoking. Most smokers know that smoking is a major cause of lung cancer and that they should not smoke - so why do they do it anyway? They might be justifying to themselves that they’re only smoking once a day so it’s not that damaging, or they might be completely ignoring all scientific evidence that smoking is harmful.

Cognitive dissonance also occurs when a person has racist beliefs that other races of people are inferior to their own. Many racists deal with this cognitive dissonance by refusing to accept any new information that would debunk their idea of one race being superior to all others. As such, they stay stuck in their own prejudiced beliefs.

The most important takeaway is that whenever you experience cognitive dissonance, try to identify which personal belief clashes with the reality of the world, and really think about whether your way of thought is problematic and needs change.

Think Further

- Describe a real-life situation where someone might experience cognitive dissonance.

- What do you think is the best way to resolve or reduce cognitive dissonance? Explain your answer.

- What are some negative consequences that can come out of poorly handling cognitive dissonance?

Teacher Resources

Sign up for our educators newsletter to learn about new content!

Educators Newsletter Email * If you are human, leave this field blank. Sign Up

Get updated about new videos!

Newsletter Email * If you are human, leave this field blank. Sign Up

Infographic

This gave students an opportunity to watch a video to identify key factors in our judicial system, then even followed up with a brief research to demonstrate how this case, which is seemingly non-impactful on the contemporary student, connect to them in a meaningful way

This is a great product. I have used it over and over again. It is well laid out and suits the needs of my students. I really appreciate all the time put into making this product and thank you for sharing.

Appreciate this resource; adding it to my collection for use in AP US Government.

I thoroughly enjoyed this lesson plan and so do my students. It is always nice when I don't have to write my own lesson plan

Sign up to receive our monthly newsletter!

- Academy 4SC

- Educators 4SC

- Leaders 4SC

- Students 4SC

- Research 4SC

Accountability

McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )

Videos Concepts Unwrapped View All 36 short illustrated videos explain behavioral ethics concepts and basic ethics principles. Concepts Unwrapped: Sports Edition View All 10 short videos introduce athletes to behavioral ethics concepts. Ethics Defined (Glossary) View All 64 animated videos - 2 to 3 minutes each - define key ethics terms and concepts. Ethics in Focus View All One-of-a-kind videos highlight the ethical aspects of current and historical subjects. Giving Voice To Values View All Eight short videos present the 7 principles of values-driven leadership from Gentile's Giving Voice to Values. In It To Win View All A documentary and six short videos reveal the behavioral ethics biases in super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff's story. Scandals Illustrated View All 30 videos - one minute each - introduce newsworthy scandals with ethical insights and case studies. Video Series

Concepts Unwrapped UT Star Icon

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is the psychological discomfort that we feel when our minds entertain two contradictory concepts at the same time.

Discussion Questions

1. In 1954, a cult leader predicted the end of the world. The world did not end, yet her followers believed in her more fervently than ever when she began making new predictions. Does this sound like there might be some cognitive dissonance at play? Explain.

2. Can you think of a time when you suffered from cognitive dissonance? Explain.

3. How about moral dissonance?

4. Have you ever seen someone, perhaps in your private life or maybe a public figure you were observing, act as Professor Luban describes? Perhaps they had long opposed a particular policy or practice and then, all of a sudden when their interests changed, so did their position on that policy or practice. Explain.

5. Can you think of a time when your gut got that guilty feeling and kept you from making a moral mistake?

6. Can you think of a time when you ignored your gut and later wished you hadn’t?

Case Studies

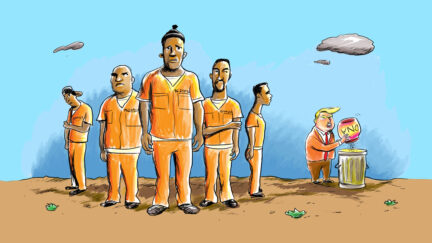

The Central Park Five

Despite the indisputable and overwhelming evidence of the innocence of the Central Park Five, some involved in the case refuse to believe it.

Related Terms

Cognitive dissonance is the mental stress people feel when they hold two contradictory ideas in their mind at the same time.

Teaching Notes

This video introduces the notion of cognitive dissonance, which has been a popular term in psychology since Leon Festinger coined it in the 1950s. As noted in the video, when dissonance involves moral issues, it is often called “moral dissonance” or “ethical dissonance.” If I resist contradictory evidence regarding my stated position that I am the smartest person I know, that’s probably a manifestation of cognitive dissonance. If I resist contradictory evidence regarding my personal view of myself as a good person, that’s likely a manifestation of moral dissonance.

When teaching cognitive dissonance, some like to quote Upton Sinclair: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” Does that sound like a version of cognitive dissonance at work? Because the prosecutors and police officers in the case study took actions that had profound impacts on other people, their actions had a strong moral dimension so the case definitely raises questions of moral dissonance.

As the video notes, one of the primary ways that people reduce cognitive dissonance arising from the clash between their vision of themselves as good people and the reality that they have done something that they shouldn’t have is to resort to rationalizations. Therefore, a viewing of our video In It To Win: Jack & Rationalizations is definitely in order when discussing cognitive dissonance.

An example of the impact of cognitive dissonance arises from pharmaceutical companies paying doctors to give talks on the efficacy of their drugs:

[Big Pharma] found that after giving a short lecture about the benefits of a certain drug, the speaker would begin to believe his own words and soon prescribe accordingly. Psychological studies show that we quickly and easily start believing whatever comes out of our own mouths, even when the original reason for expressing the opinion is no longer relevant (in the doctors’ case, that they were paid to say it.). This is cognitive dissonance at play.

The final discussion question asks what other Ethics Unwrapped videos might be relevant to the original conviction of the Central Park 5. Among others would be: (a) the conformity bias , (b) groupthink , (c) the overconfidence bias , (d) implicit bias , and (e) moral myopia .

Additional Resources

The latest resource from Ethics Unwrapped is a book, Behavioral Ethics in Practice: Why We Sometimes Make the Wrong Decisions , written by Cara Biasucci and Robert Prentice. This accessible book is amply footnoted with behavioral ethics studies and associated research. It also includes suggestions at the end of each chapter for related Ethics Unwrapped videos and case studies. Some instructors use this resource to educate themselves, while others use it in lieu of (or in addition to) a textbook.

Cara Biasucci also recently wrote a chapter on integrating Ethics Unwrapped in higher education, which can be found in the latest edition of Teaching Ethics: Instructional Models, Methods and Modalities for University Studies . The chapter includes examples of how Ethics Unwrapped is used at various universities.

The most recent article written by Cara Biasucci and Robert Prentice describes the basics of behavioral ethics and introduces Ethics Unwrapped videos and supporting materials along with teaching examples. It also includes data on the efficacy of Ethics Unwrapped for improving ethics pedagogy across disciplines. Published in Journal of Business Law and Ethics Pedagogy (Vol. 1, August 2018), it can be downloaded here: “ Teaching Behavioral Ethics (Using “Ethics Unwrapped” Videos and Educational Materials) .”

An article written by Ethics Unwrapped authors Minette Drumwright, Robert Prentice, and Cara Biasucci introduce key concepts in behavioral ethics and approaches to effective ethics instruction—including sample classroom assignments. Published in the Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, it can be downloaded here: “ Behavioral Ethics and Teaching Ethical Decision Making .”

A detailed article written by Robert Prentice, with extensive resources for teaching behavioral ethics, was published in Journal of Legal Studies Education and can be downloaded here: “ Teaching Behavioral Ethics .”

Another article by Robert Prentice, discussing how behavioral ethics can improve the ethicality of human decision-making, was published in the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy . It can be downloaded here: “ Behavioral Ethics: Can It Help Lawyers (And Others) Be their Best Selves? ”

A dated (but still serviceable) introductory article about teaching behavioral ethics can be accessed through Google Scholar by searching: Prentice, Robert A. 2004. “ Teaching Ethics, Heuristics, and Biases .” Journal of Business Ethics Education 1 (1): 57-74.

Transcript of Narration

Written and Narrated by

Robert Prentice , J.D. Business, Government & Society Department McCombs School of Business The University of Texas at Austin

Cognitive dissonance is the psychological discomfort that we feel when our minds entertain two contradictory concepts at the same time. For example: I should smoke because I enjoy it, and I shouldn’t smoke because it causes cancer. When the concepts have ethical implications, this discomfort is called moral dissonance or ethical dissonance.

Almost all people except psychopaths have a mental picture of themselves as ethical people. But sometimes people find themselves acting in unethical ways. This creates cognitive dissonance. The important thing is how people resolve that moral dissonance. Suppose you think of yourself as a good person, but your boss asked you to mislead customers about the reliability of your company’s new product. This situation creates cognitive dissonance that is psychologically and emotionally uncomfortable. In this context, the dissonance seems to manifest as guilt, an unpleasant emotion that you will wish to resolve.

Now some people will react to this dissonance by refusing to mislead customers, opting to resolve the conflict by acting honestly in order to preserve their self-image. Unfortunately, many people will resolve the dissonance without doing the right thing. For example, they may decide that product misrepresentations are not so unethical after all, because well, customers should be able to look out for themselves. Or they may rationalize that they are only doing what they’ve been ordered to do and therefore they are still good people even though they are doing bad things it’s someone else’s fault. Or they may try to learn as little as possible about the product so they can view their misrepresentations as innocently ignorant rather than intentionally dishonest.

Professor David Luban has noted: “In situation after situation, literally hundreds of experiments reveal that when our conduct clashes with our prior beliefs, our beliefs swing into conformity with our conduct, without our noticing this is going on.” In other words, too often we remind ourselves that we are good people and conclude that what we are doing must not be bad because we are not the kind of people who would do bad things. The human ability to rationalize or in other ways distance ourselves from our bad acts sometimes seems unlimited and unfortunately we can quickly begin to see our wrongdoing as acceptable.

There are no easy answers to cognitive dissonance’s potential for adverse effects upon our moral decision making and actions. But here are three quick suggestions to help minimize or combat cognitive or moral dissonance. First, never ignore that guilty feeling you sometimes get. Stop and honestly analyze why you are feeling it. Second, study the many means our minds use to distance us from our immoral actions and guard against them. Third and last, get to know the most common rationalizations that people use to excuse themselves from living up to their own ethical standards and let those rationalizations be a warning to you whenever you hear yourself using them.

Stay Informed

Support our work.

IMAGES

VIDEO