An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Case control studies.

Steven Tenny ; Connor C. Kerndt ; Mary R. Hoffman .

Affiliations

Last Update: March 27, 2023 .

- Introduction

A case-control study is a type of observational study commonly used to look at factors associated with diseases or outcomes. [1] The case-control study starts with a group of cases, which are the individuals who have the outcome of interest. The researcher then tries to construct a second group of individuals called the controls, who are similar to the case individuals but do not have the outcome of interest. The researcher then looks at historical factors to identify if some exposure(s) is/are found more commonly in the cases than the controls. If the exposure is found more commonly in the cases than in the controls, the researcher can hypothesize that the exposure may be linked to the outcome of interest.

For example, a researcher may want to look at the rare cancer Kaposi's sarcoma. The researcher would find a group of individuals with Kaposi's sarcoma (the cases) and compare them to a group of patients who are similar to the cases in most ways but do not have Kaposi's sarcoma (controls). The researcher could then ask about various exposures to see if any exposure is more common in those with Kaposi's sarcoma (the cases) than those without Kaposi's sarcoma (the controls). The researcher might find that those with Kaposi's sarcoma are more likely to have HIV, and thus conclude that HIV may be a risk factor for the development of Kaposi's sarcoma.

There are many advantages to case-control studies. First, the case-control approach allows for the study of rare diseases. If a disease occurs very infrequently, one would have to follow a large group of people for a long period of time to accrue enough incident cases to study. Such use of resources may be impractical, so a case-control study can be useful for identifying current cases and evaluating historical associated factors. For example, if a disease developed in 1 in 1000 people per year (0.001/year) then in ten years one would expect about 10 cases of a disease to exist in a group of 1000 people. If the disease is much rarer, say 1 in 1,000,0000 per year (0.0000001/year) this would require either having to follow 1,000,0000 people for ten years or 1000 people for 1000 years to accrue ten total cases. As it may be impractical to follow 1,000,000 for ten years or to wait 1000 years for recruitment, a case-control study allows for a more feasible approach.

Second, the case-control study design makes it possible to look at multiple risk factors at once. In the example above about Kaposi's sarcoma, the researcher could ask both the cases and controls about exposures to HIV, asbestos, smoking, lead, sunburns, aniline dye, alcohol, herpes, human papillomavirus, or any number of possible exposures to identify those most likely associated with Kaposi's sarcoma.

Case-control studies can also be very helpful when disease outbreaks occur, and potential links and exposures need to be identified. This study mechanism can be commonly seen in food-related disease outbreaks associated with contaminated products, or when rare diseases start to increase in frequency, as has been seen with measles in recent years.

Because of these advantages, case-control studies are commonly used as one of the first studies to build evidence of an association between exposure and an event or disease.

In a case-control study, the investigator can include unequal numbers of cases with controls such as 2:1 or 4:1 to increase the power of the study.

Disadvantages and Limitations

The most commonly cited disadvantage in case-control studies is the potential for recall bias. [2] Recall bias in a case-control study is the increased likelihood that those with the outcome will recall and report exposures compared to those without the outcome. In other words, even if both groups had exactly the same exposures, the participants in the cases group may report the exposure more often than the controls do. Recall bias may lead to concluding that there are associations between exposure and disease that do not, in fact, exist. It is due to subjects' imperfect memories of past exposures. If people with Kaposi's sarcoma are asked about exposure and history (e.g., HIV, asbestos, smoking, lead, sunburn, aniline dye, alcohol, herpes, human papillomavirus), the individuals with the disease are more likely to think harder about these exposures and recall having some of the exposures that the healthy controls.

Case-control studies, due to their typically retrospective nature, can be used to establish a correlation between exposures and outcomes, but cannot establish causation . These studies simply attempt to find correlations between past events and the current state.

When designing a case-control study, the researcher must find an appropriate control group. Ideally, the case group (those with the outcome) and the control group (those without the outcome) will have almost the same characteristics, such as age, gender, overall health status, and other factors. The two groups should have similar histories and live in similar environments. If, for example, our cases of Kaposi's sarcoma came from across the country but our controls were only chosen from a small community in northern latitudes where people rarely go outside or get sunburns, asking about sunburn may not be a valid exposure to investigate. Similarly, if all of the cases of Kaposi's sarcoma were found to come from a small community outside a battery factory with high levels of lead in the environment, then controls from across the country with minimal lead exposure would not provide an appropriate control group. The investigator must put a great deal of effort into creating a proper control group to bolster the strength of the case-control study as well as enhance their ability to find true and valid potential correlations between exposures and disease states.

Similarly, the researcher must recognize the potential for failing to identify confounding variables or exposures, introducing the possibility of confounding bias, which occurs when a variable that is not being accounted for that has a relationship with both the exposure and outcome. This can cause us to accidentally be studying something we are not accounting for but that may be systematically different between the groups.

The major method for analyzing results in case-control studies is the odds ratio (OR). The odds ratio is the odds of having a disease (or outcome) with the exposure versus the odds of having the disease without the exposure. The most straightforward way to calculate the odds ratio is with a 2 by 2 table divided by exposure and disease status (see below). Mathematically, we can write the odds ratio as follows. See Figure. Case-Control Studies Odds Ratio.

Odds ratio = [(Number exposed with disease)/(Number exposed without disease) ]/[(Number not exposed to disease)/(Number not exposed without disease) ]

This can be rewritten as:

Odds ratio = [ (Number exposed with disease) x (Number not exposed without disease) ] / [ (Number exposed without disease ) x (Number not exposed with disease) ]

The odds ratio tells us how strongly the exposure is related to the disease state. An odds ratio of greater than one implies the disease is more likely with exposure. An odds ratio of less than one implies the disease is less likely with exposure and thus the exposure may be protective. For example, a patient with a prior heart attack taking a daily aspirin has a decreased odds of having another heart attack (odds ratio less than one). An odds ratio of one implies there is no relation between the exposure and the disease process.

Odds ratios are often confused with Relative Risk (RR), which is a measure of the probability of the disease or outcome in the exposed vs unexposed groups. For very rare conditions, the OR and RR may be very similar, but they are measuring different aspects of the association between outcome and exposure. The OR is used in case-control studies because RR cannot be estimated; whereas in randomized clinical trials, a direct measurement of the development of events in the exposed and unexposed groups can be seen. RR is also used to compare risk in other prospective study designs.

- Issues of Concern

The main issues of concern with a case-control study are recall bias, its retrospective nature, the need for a careful collection of measured variables, and the selection of an appropriate control group. [3] These are discussed above in the disadvantages section.

- Clinical Significance

A case-control study is a good tool for exploring risk factors for rare diseases or when other study types are not feasible. Many times an investigator will hypothesize a list of possible risk factors for a disease process and will then use a case-control study to see if there are any possible associations between the risk factors and the disease process. The investigator can then use the data from the case-control study to focus on a few of the most likely causative factors and develop additional hypotheses or questions. Then through further exploration, often using other study types (such as cohort studies or randomized clinical studies) the researcher may be able to develop further support for the evidence of the possible association between the exposure and the outcome.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Case-control studies are prevalent in all fields of medicine from nursing and pharmacy to use in public health and surgical patients. Case-control studies are important for each member of the health care team to not only understand their common occurrence in research but because each part of the health care team has parts to contribute to such studies. One of the most important things each party provides is helping identify correct controls for the cases. Matching the controls across a spectrum of factors outside of the elements of interest take input from nurses, pharmacists, social workers, physicians, demographers, and more. Failure for adequate selection of controls can lead to invalid study conclusions and invalidate the entire study.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Case-Control Studies Odds Ratio. The figure shows a 2x2 table with calculations for the odds ratio and a 95% confidence interval for it. Contributed by S Tenny, MD, MPH, MBA

Disclosure: Steven Tenny declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Connor Kerndt declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Mary Hoffman declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Tenny S, Kerndt CC, Hoffman MR. Case Control Studies. [Updated 2023 Mar 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022] Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. Crider K, Williams J, Qi YP, Gutman J, Yeung L, Mai C, Finkelstain J, Mehta S, Pons-Duran C, Menéndez C, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Feb 1; 2(2022). Epub 2022 Feb 1.

- Epidemiology Of Study Design. [StatPearls. 2024] Epidemiology Of Study Design. Munnangi S, Boktor SW. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Risk factors for Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-positive subjects in Uganda. [AIDS. 1997] Risk factors for Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-positive subjects in Uganda. Ziegler JL, Newton R, Katongole-Mbidde E, Mbulataiye S, De Cock K, Wabinga H, Mugerwa J, Katabira E, Jaffe H, Parkin DM, et al. AIDS. 1997 Nov; 11(13):1619-26.

- Review The epidemiology of classic, African, and immunosuppressed Kaposi's sarcoma. [Epidemiol Rev. 1991] Review The epidemiology of classic, African, and immunosuppressed Kaposi's sarcoma. Wahman A, Melnick SL, Rhame FS, Potter JD. Epidemiol Rev. 1991; 13:178-99.

- Review Improving Methods for Analyzing Data from Case-Only Studies [ 2022] Review Improving Methods for Analyzing Data from Case-Only Studies Mostofsky E, Ngo LH, Mittleman MA. 2022 Feb

Recent Activity

- Case Control Studies - StatPearls Case Control Studies - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Case Control Studies

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Nebraska Medical Center

- 2 Spectrum Health/Michigan State University College of Human Medicine

- PMID: 28846237

- Bookshelf ID: NBK448143

A case-control study is a type of observational study commonly used to look at factors associated with diseases or outcomes. The case-control study starts with a group of cases, which are the individuals who have the outcome of interest. The researcher then tries to construct a second group of individuals called the controls, who are similar to the case individuals but do not have the outcome of interest. The researcher then looks at historical factors to identify if some exposure(s) is/are found more commonly in the cases than the controls. If the exposure is found more commonly in the cases than in the controls, the researcher can hypothesize that the exposure may be linked to the outcome of interest.

For example, a researcher may want to look at the rare cancer Kaposi's sarcoma. The researcher would find a group of individuals with Kaposi's sarcoma (the cases) and compare them to a group of patients who are similar to the cases in most ways but do not have Kaposi's sarcoma (controls). The researcher could then ask about various exposures to see if any exposure is more common in those with Kaposi's sarcoma (the cases) than those without Kaposi's sarcoma (the controls). The researcher might find that those with Kaposi's sarcoma are more likely to have HIV, and thus conclude that HIV may be a risk factor for the development of Kaposi's sarcoma.

There are many advantages to case-control studies. First, the case-control approach allows for the study of rare diseases. If a disease occurs very infrequently, one would have to follow a large group of people for a long period of time to accrue enough incident cases to study. Such use of resources may be impractical, so a case-control study can be useful for identifying current cases and evaluating historical associated factors. For example, if a disease developed in 1 in 1000 people per year (0.001/year) then in ten years one would expect about 10 cases of a disease to exist in a group of 1000 people. If the disease is much rarer, say 1 in 1,000,0000 per year (0.0000001/year) this would require either having to follow 1,000,0000 people for ten years or 1000 people for 1000 years to accrue ten total cases. As it may be impractical to follow 1,000,000 for ten years or to wait 1000 years for recruitment, a case-control study allows for a more feasible approach.

Second, the case-control study design makes it possible to look at multiple risk factors at once. In the example above about Kaposi's sarcoma, the researcher could ask both the cases and controls about exposures to HIV, asbestos, smoking, lead, sunburns, aniline dye, alcohol, herpes, human papillomavirus, or any number of possible exposures to identify those most likely associated with Kaposi's sarcoma.

Case-control studies can also be very helpful when disease outbreaks occur, and potential links and exposures need to be identified. This study mechanism can be commonly seen in food-related disease outbreaks associated with contaminated products, or when rare diseases start to increase in frequency, as has been seen with measles in recent years.

Because of these advantages, case-control studies are commonly used as one of the first studies to build evidence of an association between exposure and an event or disease.

In a case-control study, the investigator can include unequal numbers of cases with controls such as 2:1 or 4:1 to increase the power of the study.

Disadvantages and Limitations

The most commonly cited disadvantage in case-control studies is the potential for recall bias. Recall bias in a case-control study is the increased likelihood that those with the outcome will recall and report exposures compared to those without the outcome. In other words, even if both groups had exactly the same exposures, the participants in the cases group may report the exposure more often than the controls do. Recall bias may lead to concluding that there are associations between exposure and disease that do not, in fact, exist. It is due to subjects' imperfect memories of past exposures. If people with Kaposi's sarcoma are asked about exposure and history (e.g., HIV, asbestos, smoking, lead, sunburn, aniline dye, alcohol, herpes, human papillomavirus), the individuals with the disease are more likely to think harder about these exposures and recall having some of the exposures that the healthy controls.

Case-control studies, due to their typically retrospective nature, can be used to establish a correlation between exposures and outcomes, but cannot establish causation . These studies simply attempt to find correlations between past events and the current state.

When designing a case-control study, the researcher must find an appropriate control group. Ideally, the case group (those with the outcome) and the control group (those without the outcome) will have almost the same characteristics, such as age, gender, overall health status, and other factors. The two groups should have similar histories and live in similar environments. If, for example, our cases of Kaposi's sarcoma came from across the country but our controls were only chosen from a small community in northern latitudes where people rarely go outside or get sunburns, asking about sunburn may not be a valid exposure to investigate. Similarly, if all of the cases of Kaposi's sarcoma were found to come from a small community outside a battery factory with high levels of lead in the environment, then controls from across the country with minimal lead exposure would not provide an appropriate control group. The investigator must put a great deal of effort into creating a proper control group to bolster the strength of the case-control study as well as enhance their ability to find true and valid potential correlations between exposures and disease states.

Similarly, the researcher must recognize the potential for failing to identify confounding variables or exposures, introducing the possibility of confounding bias, which occurs when a variable that is not being accounted for that has a relationship with both the exposure and outcome. This can cause us to accidentally be studying something we are not accounting for but that may be systematically different between the groups.

Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

- Introduction

- Issues of Concern

- Clinical Significance

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

Publication types

- Study Guide

What Is A Case Control Study?

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A case-control study is a research method where two groups of people are compared – those with the condition (cases) and those without (controls). By looking at their past, researchers try to identify what factors might have contributed to the condition in the ‘case’ group.

Explanation

A case-control study looks at people who already have a certain condition (cases) and people who don’t (controls). By comparing these two groups, researchers try to figure out what might have caused the condition. They look into the past to find clues, like habits or experiences, that are different between the two groups.

The “cases” are the individuals with the disease or condition under study, and the “controls” are similar individuals without the disease or condition of interest.

The controls should have similar characteristics (i.e., age, sex, demographic, health status) to the cases to mitigate the effects of confounding variables .

Case-control studies identify any associations between an exposure and an outcome and help researchers form hypotheses about a particular population.

Researchers will first identify the two groups, and then look back in time to investigate which subjects in each group were exposed to the condition.

If the exposure is found more commonly in the cases than the controls, the researcher can hypothesize that the exposure may be linked to the outcome of interest.

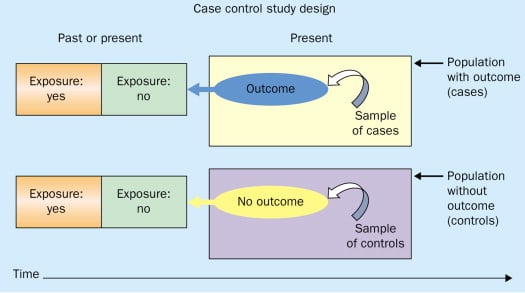

Figure: Schematic diagram of case-control study design. Kenneth F. Schulz and David A. Grimes (2002) Case-control studies: research in reverse . The Lancet Volume 359, Issue 9304, 431 – 434

Quick, inexpensive, and simple

Because these studies use already existing data and do not require any follow-up with subjects, they tend to be quicker and cheaper than other types of research. Case-control studies also do not require large sample sizes.

Beneficial for studying rare diseases

Researchers in case-control studies start with a population of people known to have the target disease instead of following a population and waiting to see who develops it. This enables researchers to identify current cases and enroll a sufficient number of patients with a particular rare disease.

Useful for preliminary research

Case-control studies are beneficial for an initial investigation of a suspected risk factor for a condition. The information obtained from cross-sectional studies then enables researchers to conduct further data analyses to explore any relationships in more depth.

Limitations

Subject to recall bias.

Participants might be unable to remember when they were exposed or omit other details that are important for the study. In addition, those with the outcome are more likely to recall and report exposures more clearly than those without the outcome.

Difficulty finding a suitable control group

It is important that the case group and the control group have almost the same characteristics, such as age, gender, demographics, and health status.

Forming an accurate control group can be challenging, so sometimes researchers enroll multiple control groups to bolster the strength of the case-control study.

Do not demonstrate causation

Case-control studies may prove an association between exposures and outcomes, but they can not demonstrate causation.

A case-control study is an observational study where researchers analyzed two groups of people (cases and controls) to look at factors associated with particular diseases or outcomes.

Below are some examples of case-control studies:

- Investigating the impact of exposure to daylight on the health of office workers (Boubekri et al., 2014).

- Comparing serum vitamin D levels in individuals who experience migraine headaches with their matched controls (Togha et al., 2018).

- Analyzing correlations between parental smoking and childhood asthma (Strachan and Cook, 1998).

- Studying the relationship between elevated concentrations of homocysteine and an increased risk of vascular diseases (Ford et al., 2002).

- Assessing the magnitude of the association between Helicobacter pylori and the incidence of gastric cancer (Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group, 2001).

- Evaluating the association between breast cancer risk and saturated fat intake in postmenopausal women (Howe et al., 1990).

Frequently asked questions

1. what’s the difference between a case-control study and a cross-sectional study.

Case-control studies are different from cross-sectional studies in that case-control studies compare groups retrospectively while cross-sectional studies analyze information about a population at a specific point in time.

In cross-sectional studies , researchers are simply examining a group of participants and depicting what already exists in the population.

2. What’s the difference between a case-control study and a longitudinal study?

Case-control studies compare groups retrospectively, while longitudinal studies can compare groups either retrospectively or prospectively.

In a longitudinal study , researchers monitor a population over an extended period of time, and they can be used to study developmental shifts and understand how certain things change as we age.

In addition, case-control studies look at a single subject or a single case, whereas longitudinal studies can be conducted on a large group of subjects.

3. What’s the difference between a case-control study and a retrospective cohort study?

Case-control studies are retrospective as researchers begin with an outcome and trace backward to investigate exposure; however, they differ from retrospective cohort studies.

In a retrospective cohort study , researchers examine a group before any of the subjects have developed the disease, then examine any factors that differed between the individuals who developed the condition and those who did not.

Thus, the outcome is measured after exposure in retrospective cohort studies, whereas the outcome is measured before the exposure in case-control studies.

Boubekri, M., Cheung, I., Reid, K., Wang, C., & Zee, P. (2014). Impact of windows and daylight exposure on overall health and sleep quality of office workers: a case-control pilot study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 10 (6), 603-611.

Ford, E. S., Smith, S. J., Stroup, D. F., Steinberg, K. K., Mueller, P. W., & Thacker, S. B. (2002). Homocyst (e) ine and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of the evidence with special emphasis on case-control studies and nested case-control studies. International journal of epidemiology, 31 (1), 59-70.

Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. (2001). Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut, 49 (3), 347-353.

Howe, G. R., Hirohata, T., Hislop, T. G., Iscovich, J. M., Yuan, J. M., Katsouyanni, K., … & Shunzhang, Y. (1990). Dietary factors and risk of breast cancer: combined analysis of 12 case—control studies. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 82 (7), 561-569.

Lewallen, S., & Courtright, P. (1998). Epidemiology in practice: case-control studies. Community eye health, 11 (28), 57–58.

Strachan, D. P., & Cook, D. G. (1998). Parental smoking and childhood asthma: longitudinal and case-control studies. Thorax, 53 (3), 204-212.

Tenny, S., Kerndt, C. C., & Hoffman, M. R. (2021). Case Control Studies. In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing.

Togha, M., Razeghi Jahromi, S., Ghorbani, Z., Martami, F., & Seifishahpar, M. (2018). Serum Vitamin D Status in a Group of Migraine Patients Compared With Healthy Controls: A Case-Control Study. Headache, 58 (10), 1530-1540.

Further Information

- Schulz, K. F., & Grimes, D. A. (2002). Case-control studies: research in reverse. The Lancet, 359(9304), 431-434.

- What is a case-control study?

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Research Design: Case-Control Studies

Chittaranjan andrade.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Chittaranjan Andrade, Dept. of Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neurotoxicology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, Karnataka 560029, India. E-mail: [email protected]

Issue date 2022 May.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access page ( https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage ).

Case-control studies are observational studies in which cases are subjects who have a characteristic of interest, such as a clinical diagnosis, and controls are (usually) matched subjects who do not have that characteristic. After cases and controls are identified, researchers “look back” to determine what past events (exposures), if any, are significantly associated with caseness. For “looking back,” data may be obtained by clinical history-taking or from medical records such as case files or large electronic health care databases. The data are analyzed using logistic regression, which adjusts for confounding variables and yields an odds ratio and a probability value for the association between the exposure of interest (independent variable) and caseness (dependent variable). Because case-control studies are not randomized controlled studies, cause–effect relationships do not necessarily explain significant associations detected in the regressions; unexplored confounding may be responsible. These concepts are explained with the help of examples.

Keywords: Case-control studies, research design, logistic regression

Earlier articles in this series described classifications in research design, 1 prospective and retrospective studies, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, 2 and cohort studies. 3 This article considers a research design that is often used in present-day research in medicine and psychiatry: the case-control study.

Case-Control Study: General Description

A case-control study is one in which cases are compared with controls to identify historical exposures that are significantly associated with a current state or, stated in different words, variables that are significantly associated with caseness. In case-control studies, cases are subjects with a particular characteristic. The characteristic that defines caseness may be a clinical diagnosis (e.g., schizophrenia [Sz]), a treatment outcome (e.g., treatment-resistance), a side effect (e.g., tardive dyskinesia), or any other characteristic that is the subject of interest. Controls are subjects who do not have the characteristic that defines caseness. For Sz, controls may be healthy controls; for treatment-resistance, controls would be subjects with the same diagnosis and who are treatment-responsive; for tardive dyskinesia, controls would be subjects who received the same treatment but did not develop this adverse outcome. Controls are commonly selected based on matching with cases for variables such as age, sex, site of recruitment, and other variables. Matching may be 1:1, but when data are drawn from large electronic databases, it is often possible to match five or even 10 controls with each case. In such studies, there may be thousands of cases and tens or even hundreds of thousands of controls.

As an actual example of a case-control study, children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may be compared with normally developing children to determine whether a history of maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy is more frequent among cases than among controls; if it is, and if the association remains statistically significant after adjusting for confounding variables, one may speculate that gestational exposure to antidepressants predisposes to autism spectrum disorder. 4 Here, readers may note that there is only one exposure of interest: gestational exposure to antidepressant drugs.

As a hypothetical example of a case-control study, patients with Sz may be compared with healthy controls to determine whether a family history of Sz, viral infection during pregnancy, season of birth, obstetric complications during pregnancy, brain insults in early childhood, and other variables are associated with Sz in the sample. Here, readers may note that all the variables listed are exposures of interest and corrections are desirable to protect against the risk of Type 1 statistical error associated with multiple hypothesis testing. 5

In summary, in case-control studies, there are cases and there are controls that are matched with cases. Researchers then “look back” to ascertain what past events (exposures) are associated with caseness. The exposures of interest may be one or many.

Analysis of Case-Control Studies

Case-control studies are analyzed using logistic regression. The dependent variable is the (dichotomous) grouping variable: case vs. control. The independent variables are the exposure(s) of interest plus the confounding variables whose effects must be adjusted for in the regression to understand the unique effect of the exposure variable(s). The logistic regression yields an odds ratio and a statistical significance (P) value for each independent variable; this allows us to understand whether or not the independent variables are significantly associated with caseness, and, if they are, what the effect sizes are, as exemplified by the odds ratios. Readers may note that whether a significant association is a marker of risk or a cause of the risk cannot be determined from an observational study; this was explained in an earlier article. 3

As a special note, when cases and controls are well matched on many important variables, a procedure known as conditional logistic regression analysis may be employed. 6

Characteristics of Case-Control Studies

How do case-control studies fit into classifications of research design described in an earlier article? 1 Case-control studies are empirical studies that are based on samples, not individual cases or case series. They are cross-sectional because cases and controls are identified and evaluated for caseness, historical exposures, and confounding variables at a single point in time. They are observational; there is no intervention. They are prospective when cases and controls are identified and interviewed in real time, such as in an outpatient department, and retrospective when they are identified in and studied from medical records or electronic health care databases. Strengths and limitations of prospectively vs. retrospectively ascertained data were described in an earlier article. 3

The nested case-control study is a special situation in which cases and controls are both identified from within a cohort. So, instead of studying the entire cohort, which would be time- and labor- intensive, the researchers study only cases and matched controls within that cohort. 7 To explain with the help of an actual example, Gronich et al. 8 examined the electronic database of the largest health care provider in Israel and identified a cohort of 1,762,164 adults who did not have a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD). During follow-up, 11,314 patients were newly diagnosed with PD. Each patient (case) was matched with 10 randomly selected controls based on age, sex, ethnicity, and duration of follow-up. Thus, rather than extracting data for 11,314 cases and the rest of the 1,762,164 adults who did not develop PD and who were therefore noncases, the authors carved out a smaller sample of controls from within the cohort. Thus, the final sample of 11,314 cases and 113,140 controls was “nested” within the original cohort; studying this smaller sample took less time and was less labor-intensive than studying the entire cohort.

Parting Notes

There are two reasons why, in case-control studies, large samples are desirable, and why many controls may be matched to a single case. One reason is that patients are not randomized to be cases or controls. In such circumstances, as in quasi-controlled studies, 9 there is bound to be confounding. With larger samples, statistical power to adjust for confounding will improve. The other reason is that, in case-control studies, data are usually drawn from medical records or databases. Information extracted from such sources is very unlikely to have been collected and recorded with the expectation of use in future research. So, there are bound to be inaccuracies. When data are blurred (inaccurate), there is statistical noise. When the sample size is large, it becomes easier to see a signal through the noise.

Cohort and case-control study designs are not “opposites” as are prospective vs. retrospective, or cross-sectional vs. longitudinal, or controlled vs. uncontrolled research designs. Rather, like the randomized controlled and quasi-controlled designs, these designs are special kinds of research design in the controlled vs. uncontrolled classification. Note that whereas a case-control study is always a special kind of controlled study, a cohort study can be classified under controlled or uncontrolled, depending on whether or not there is a comparison group for the group of interest.

Case-control studies in India tend to be poor in quality because they are based on small sample sizes. Small samples do not have sufficient statistical power to adjust for the multitude of confounding variables that bedevil research in psychiatry. Large samples cannot be identified because India does not as yet have large electronic health care databases as a source of data.

Finally, case-control studies, like cohort studies, are observational in nature, and authors who conduct and report such studies should follow the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

- 1. Andrade C. Describing research design. Indian J Psychol Med, 2019; 41: 201–202. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Andrade C. Simultaneous descriptors of research design. Indian J Psychol Med, 2021; 43(6): 83–84. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Andrade C. Research design: cohort studies. Indian J Psychol Med, 2022; 44(1): (in press). [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Croen LA, Grether JK, Yoshida CK, et al. Antidepressant use during pregnancy and childhood autism spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2011; 68(11): 1104–1112. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Andrade C. Author’s response to multiple testing and protection against type I error using P value correction: Application in cross-sectional study designs. Indian J Psychol Med, 2019; 41(2): 198. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Kuo C-L, Duan Y, and Grady J. Unconditional or conditional logistic regression model for age-matched case-control data? Front Public Health, 2018; 6: 57. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Ernster VL. Nested case-control studies. Prev Med, 1994; 23(5): 587–590. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Gronich N, Abernethy DR, Auriel E, et al. Beta2-adrenoceptor agonists and antagonists and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord, 2018; 33(9): 1465–1471. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Andrade C. The limitations of quasi-experimental studies, and methods for data analysis when a quasi-experimental research design is unavoidable. Indian J Psychol Med, 2021; 43(5): 451–452. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (723.0 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Study Design 101: Case Control Study

- Case Report

- Case Control Study

- Cohort Study

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- Practice Guideline

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Helpful Formulas

- Finding Specific Study Types

A study that compares patients who have a disease or outcome of interest (cases) with patients who do not have the disease or outcome (controls), and looks back retrospectively to compare how frequently the exposure to a risk factor is present in each group to determine the relationship between the risk factor and the disease.

Case control studies are observational because no intervention is attempted and no attempt is made to alter the course of the disease. The goal is to retrospectively determine the exposure to the risk factor of interest from each of the two groups of individuals: cases and controls. These studies are designed to estimate odds.

Case control studies are also known as "retrospective studies" and "case-referent studies."

- Good for studying rare conditions or diseases

- Less time needed to conduct the study because the condition or disease has already occurred

- Lets you simultaneously look at multiple risk factors

- Useful as initial studies to establish an association

- Can answer questions that could not be answered through other study designs

Disadvantages

- Retrospective studies have more problems with data quality because they rely on memory and people with a condition will be more motivated to recall risk factors (also called recall bias).

- Not good for evaluating diagnostic tests because it's already clear that the cases have the condition and the controls do not

- It can be difficult to find a suitable control group

Design pitfalls to look out for

Care should be taken to avoid confounding, which arises when an exposure and an outcome are both strongly associated with a third variable. Controls should be subjects who might have been cases in the study but are selected independent of the exposure. Cases and controls should also not be "over-matched."

Is the control group appropriate for the population? Does the study use matching or pairing appropriately to avoid the effects of a confounding variable? Does it use appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria?

Fictitious Example

There is a suspicion that zinc oxide, the white non-absorbent sunscreen traditionally worn by lifeguards is more effective at preventing sunburns that lead to skin cancer than absorbent sunscreen lotions. A case-control study was conducted to investigate if exposure to zinc oxide is a more effective skin cancer prevention measure. The study involved comparing a group of former lifeguards that had developed cancer on their cheeks and noses (cases) to a group of lifeguards without this type of cancer (controls) and assess their prior exposure to zinc oxide or absorbent sunscreen lotions.

This study would be retrospective in that the former lifeguards would be asked to recall which type of sunscreen they used on their face and approximately how often. This could be either a matched or unmatched study, but efforts would need to be made to ensure that the former lifeguards are of the same average age, and lifeguarded for a similar number of seasons and amount of time per season.

Real-life Examples

Boubekri, M., Cheung, I., Reid, K., Wang, C., & Zee, P. (2014). Impact of windows and daylight exposure on overall health and sleep quality of office workers: a case-control pilot study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 10 (6), 603-611. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.3780

This pilot study explored the impact of exposure to daylight on the health of office workers (measuring well-being and sleep quality subjectively, and light exposure, activity level and sleep-wake patterns via actigraphy). Individuals with windows in their workplaces had more light exposure, longer sleep duration, and more physical activity. They also reported a better scores in the areas of vitality and role limitations due to physical problems, better sleep quality and less sleep disturbances.

Togha, M., Razeghi Jahromi, S., Ghorbani, Z., Martami, F., & Seifishahpar, M. (2018). Serum Vitamin D Status in a Group of Migraine Patients Compared With Healthy Controls: A Case-Control Study. Headache, 58 (10), 1530-1540. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13423

This case-control study compared serum vitamin D levels in individuals who experience migraine headaches with their matched controls. Studied over a period of thirty days, individuals with higher levels of serum Vitamin D was associated with lower odds of migraine headache.

Related Formulas

- Odds ratio in an unmatched study

- Odds ratio in a matched study

Related Terms

A patient with the disease or outcome of interest.

Confounding

When an exposure and an outcome are both strongly associated with a third variable.

A patient who does not have the disease or outcome.

Matched Design

Each case is matched individually with a control according to certain characteristics such as age and gender. It is important to remember that the concordant pairs (pairs in which the case and control are either both exposed or both not exposed) tell us nothing about the risk of exposure separately for cases or controls.

Observed Assignment

The method of assignment of individuals to study and control groups in observational studies when the investigator does not intervene to perform the assignment.

Unmatched Design

The controls are a sample from a suitable non-affected population.

Now test yourself!

1. Case Control Studies are prospective in that they follow the cases and controls over time and observe what occurs.

a) True b) False

2. Which of the following is an advantage of Case Control Studies?

a) They can simultaneously look at multiple risk factors. b) They are useful to initially establish an association between a risk factor and a disease or outcome. c) They take less time to complete because the condition or disease has already occurred. d) b and c only e) a, b, and c

Evidence Pyramid - Navigation

- Meta- Analysis

- Case Reports

- << Previous: Case Report

- Next: Cohort Study >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 10:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/studydesign101

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2962

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

IMAGES

COMMENTS

A case-control study is an experimental design that compares a group of participants possessing a condition of interest to a very similar group lacking that condition.

A case-control study is a type of observational study commonly used to look at factors associated with diseases or outcomes. The case-control study starts with a group of cases, which are the individuals who have the outcome of interest.

A case-control study is a type of observational study commonly used to look at factors associated with diseases or outcomes. The case-control study starts with a group of cases, which are the individuals who have the outcome of interest.

A case-control study is a research method where two groups of people are compared – those with the condition (cases) and those without (controls). By looking at their past, researchers try to identify what factors might have contributed to the condition in the ‘case’ group.

Introduce basic concepts, application, and issues of case-control studies. Understand key considerations in designing a case-control study, such as confounding and matching. How to determine sample size for a prospective case-control study.

Case-control studies are observational studies in which cases are subjects who have a characteristic of interest, such as a clinical diagnosis, and controls are (usually) matched subjects who do not have that characteristic.

Case-control studies are particularly appropriate for studying disease outbreaks, rare diseases, or outcomes of interest. This article describes several types of case-control designs, with simple graphical displays to help understand their differences.

Case-control studies are particularly appropriate for studying disease outbreaks, rare diseases, or out-comes of interest. This article describes several types of case-control designs, with simple graphical displays to help understand their differences.

The goal is to retrospectively determine the exposure to the risk factor of interest from each of the two groups of individuals: cases and controls. These studies are designed to estimate odds. Case control studies are also known as "retrospective studies" and "case-referent studies."

Case-control studies are a type of observational epidemiological study that involve comparing two groups of individuals; one group with a defined outcome and the other without (normal). By doing this, one can look back in time to analyze the possible factors that may have contributed to the development of that outcome.